This Norwegian frigate (Helge Ingstad) has sailed today into Severomorsk to partake in the Victory Day parade – and then in the joint exercises Pomor-2013.

Putin awards grants at the Russian Geographic Society

Russian media barely noticed the meeting of the Russian Geographic Society (on 30 April), where President Putin awarded generous grants, including for a documentary on the Polar expedition of Vladimir Rusanov, lost back in 1903. This picture is from that period – Konstantin Korovin, ‘Sever’ (from the so valuable Wikipedia). Among smaller grants – the… Read more »

Russia’s Arctic ‘possessions’

This concise article in Nezavisimaya Gazeta gives a good impression on the conference focused on the Sevmorput prospects in the Shirshov Institute. A more alarmist analysis on China’s penetration into Russia’s Arctic ‘possessions’ appeared a month ago.

‘Start celebrating’

I examined carefully Putin’s extra-long Q-&-A ‘Direct Line’ for any matters of relevance for the Arctic, and there was indeed one question about instituting a Day of Polar Explorer – and Putin’s laconic answer was – ‘Start celebrating’. Not that surprising considering that the Arctic was barely mentioned in his series of articles outlining his… Read more »

Strategy for the Arctic Zone Development 2020

I thought that a must-have thing for a blog on Russia and the Arctic is a link to the Strategy for the Arctic Zone Development 2020 approved by President Putin in February 2013. To my chagrin, I am unable to find an official English translation, but the Russian text is here. The document is remarkably… Read more »

Seminar on Arctic security

The first entry in this newly-born blog is about the capstone seminar on the Arctic security that the IISS organized in Stockholm on 19 April 2013. My task was to comment on the presentations of two foreign ministers: Carl Bildt from Sweden and Erkki Tuomijola from Finland. My prepared opening was “These presentations are not… Read more »

Public Trust in the State

For a society such as the Norwegian one, public trust in the state is a cornerstone. But what happens when that trust is lacking?

CC0 Public Domain. Downloaded from Pixabay

In several cases over the past year (2012), the involvement of Norway’s Child Protection Service (“Barnevernet”) with families of immigrant background has been the subject of heated debate. The rights and wrongs of Barnevernet’s actions in individual cases are impossible for the general public to evaluate on the basis of media reports. For very good reasons, Barnevernet is subject to a duty of confidentiality in the child’s best interests. Despite an intense desire for more information, we must respect this confidentiality. But this respect is conditional on the existence of public trust in Barnevernet among the population at large – including among people of immigrant background.

This autumn, Polish people in Norway, as well as in Poland and in other countries, were able to view two documentaries made in 2012 about child protection in Norway. The documentaries included interviews with Polish families in Norway who had had bad experiences with Barnevernet and its working methods. There was a focus on the families’ lack of legal safeguards in the face of Barnevernet’s allegedly high-handed and arbitrary actions. The parents felt as though they lacked any legal rights against a state that had deprived them of what was most precious to them – their children. The extent to which there were grounds for Barnevernet to intervene in any specific case is beyond the scope of this article. Rather the article’s point is that among Polish immigrants in Norway the prevailing view of Barnevernet is one of scepticism and fear. In discussions both amongst Poles in Norway and with their relatives and friends in Poland and other countries, the predominating view of Barnevernet is that of an organisation that has no respect for the family, and that is almost above the law. At the same time there is little in the public debate in Norway that helps balance such a view of Barnevernet, even though the heated debate about Barnevernet’s role and position is far from confined to immigrant circles.

I have interviewed 75 persons from Norwegian-Pakistani and Polish backgrounds over the past year in connection with a research project, and the topic of child protection has been spontaneously introduced by several interviewees. My research project is about the attitudes of immigrants and their children towards their country of residence, and how they view the possibility of at some point moving back to their own or their parents’ country of origin. In other words, the project has absolutely nothing to do with children or child neglect. Nevertheless, the topic was raised. Given the media attention devoted to child protection cases involving immigrant families over the past year, this is perhaps unsurprising. At the same time, I think it is surprising that someone, in a discussion about life in Norway, would choose to raise the topic of child protection. I have no doubt that there is a basic lack of trust in Barnevernet as an institution among the people I have interviewed. In fact, there is a deep mistrust: when we spoke further about their experiences of life in Norway, the interviewees continually raised new issues concerning legal safeguards for parents, for example in relation to exchanges of information between kindergartens, public health centres, school psychology services and Barnevernet. The focus of the discussion was either on legal safeguards and possibilities for appealing official decisions, or quite simply on fear and disempowerment.

Most immigrants in Norway work and pay their taxes as law-abiding citizens. But many of those I have spoken to do not believe that the authorities, as represented by Barnevernet, act “in the child’s best interests”. This lack of trust cannot be explained in this context as the result of cultural differences concerning child upbringing or disagreement about the need in some cases to protect children against their own parents. Rather it is based on a genuine fear that Barnevernet does not safeguard the child’s best interest and that parents at worst may be left without any legal redress.

The starting point for a democratic society must be that we – the people – have trust in the institutions of the state. A fundamental principle is that we have trust in a legal system that enables us to challenge decisions that we do not agree with. At the same time we know that human error and system failures mean that even the institutions of the state are not always without fault. This is knowledge that citizens in Norwegian society acquire through a combination of school, personal experience, and information gleaned from the society around us. But how do we ensure that people who arrive in Norway as adults also acquire this knowledge, possession of which is in the best interests of both themselves and our society, including those institutions that sometimes make mistakes and need correction?

As one of the extended arms of the State, Barnevernet is dependent on having the trust of the entire population. Barnevernet works with families and children, and clearly has to take many difficult decisions. Where the question is whether a child should live with his or her biological parents, there will often be disagreement about the decision. In that situation it is crucial that we all have trust in the assessments and decisions that Barnevernet makes on our behalf and in the child’s best interests. This is true for all families, whether or not they have an immigrant background.

What is Barnevernet doing today to address the challenge of Norway’s changing demographic make-up? Is it possible to respect a child’s rights so as to safeguard that child’s whole identity, even when radical measures are needed? For example, will it be possible to find families who have the same linguistic, cultural and religious backgrounds, if this is also important for the child? Someone from a Polish background who suspects that a child in his or her circle is being neglected may perhaps not report his or her concerns to Barnevernet. This means that Barnevernet will lose the opportunity to resolve the problem at an early stage, which would be in the best interests of the child, the parents and of society as a whole. Even though many immigrants’ fears of local child protection services may be groundless, these fears hamper Barnevernet’s ability to do its job: to protect the children who need its help.

- This text was published in Norwegian in the daily Dagbladet 19 December 2012: Tillit til staten

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext

Peace for Our Time?

Azar Gat, giving the PRIO Annual Peace Address 2012. Photo: Kristian Hoelscher, PRIO

When the organizers of this event suggested ‘peace for our time?’, with a question mark at the end, as the half-whimsical title for this lecture, I accepted gladly. As you are all aware, this was what the British prime-minister Neville Chamberlain promised the cheering crowds that received him on his return from Munich in September 1938, waving the agreement he reached with Herr Hitler on the peaceful resolution of the Czechoslovakian conflict.

And yet, in less than six months Hitler occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia, and in less than a year, Europe – and soon after the world – were in the grips of another World War which cost the lives of an estimated 55 million people. Chamberlain, with his umbrella, acquired an eternal image of a clown, and his prophecy of peace – together with similar prophesies of the ‘war to end all wars’ during and after WWI, and a New World Order after the Cold War – may serve as a warning against any pronouncement regarding the demise of war.

Such pronouncements are always in danger of being premature, as Mark Twain quipped about the news of his own death. Thus, I will not try to prophesize the future, which is always open and the realm of probabilities. Instead, I shall concentrate on past trends – including the close and most recent past – to show that war has indeed been decreasing and peace expanding. I shall try to explain why this has been so, and what fed pronouncements such as that by Chamberlain and the others mentioned here, never made by active statesmen – as opposed to prophets or moralists – before modern times. They weren’t entirely misguided after all.

The claim that war has been decreasing in stages throughout history has been made by several scholars during the past decade or two, including recently in Steven Pinker’s best-selling book The Better Angels of Our Nature. The first sharp reduction in human fighting resulted from the rise of the state-Leviathan from around 5000 years ago in the most pioneering parts of the world. In Norway, for example, one of the world’s late developers, like the rest of northern and western Europe, the process only took off about one thousand years ago – though you have done pretty well since then, in contrast to your earlier rough record. Indeed, several comprehensive studies of the subject have demonstrated on the basis of anthropological and archaeological evidence that Hobbes’s picture of the anarchic state of nature was fundamentally true. The Rousseauite image of a peaceful aboriginal human past corrupted by the adoption of agriculture, private property and the state, an image that dominated mid-twentieth century anthropology and popular culture, has been proven to be unfounded.

Leading the Charge Against Injustice

Abraham Lincoln once said: ‘It is hard to lead a cavalry charge if you think you look funny on a horse.’ It takes belief and faith, it takes self-confidence and persistence, to lead a cavalry charge against injustice – and John Lewis has displayed all of those qualities. He has led many charges. I have for a long time been intensely interested in American politics, the civil rights struggle, and the rise of an incredibly strong field of African-American politicians and activists – from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Jesse Jackson, Jr.; from Andrew Young to Barack Obama to, indeed, John Lewis, and so many others. It is a great honor for me to stand here next to one of these greats, a true hero. [This text is a transcript of Henrik Syse’s comments to John Lewis’ PRIO Annual Peace Address, given 28 Sep 2011).Read More

Non-violent Struggles: Scholarship, Policy and Realities

Thank you to PRIO for the opportunity to join you today and to Congressman John Lewis for his insights into the use of nonviolence in the American civil rights movement. [This text is a transcript of Kathleen G. Cunningham’s comments to John Lewis’ PRIO Annual Peace Address].

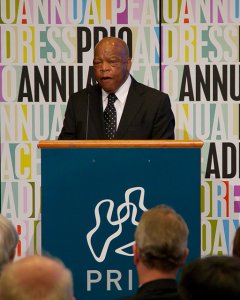

John Lewis giving the PRIO Annual Peace Address in 2011.

What I hope to add today with my own comments is a synthesis of the scholarship on nonviolence with the realities of nonviolent struggles today and to explore the pressing policy questions that emerge from the study of nonviolence and its application to these real world challenges.

Let me begin by highlighting the phenomenal changes we have seen these past months in North Africa and the Middle East and roles that violence and nonviolence have played there. As you all know, in the past 10 months, we have seen social revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, civil war in Libya, uprisings in Bahrain, Syria and Yemen, and protests breaking out in a number of other countries. Many of the struggles have relied on nonviolent tactics to press their governments for radical social change. In some cases, violence has erupted between protesters and government forces. In others, we see large scale uses of violence.

These movements, both nonviolent and violent have led to concessions from a number of governments, and three regime changes, but also to repression and conflict. These events were both riveting and in some ways shocking. Few would have predicted this change, or the means through which it occurred. The possibility of radical social change brought about through nonviolent protest in the Middle East was not something many people were entertaining prior to the mass protests in Tunisia.

These events, and in particular the stark comparison of how social change was achieved relatively peacefully in Tunisia and Egypt but though violent upheaval in Libya, have recalled the necessity of understanding when civil resistance can work, and why protesters turn to violence in some cases but not others.

Historically, much of the scholarship on nonviolence is instructive, descriptive, or normative. The work of Gene Sharp, for example, has served as a practical guide for nonviolent resistance and played a role in struggles to overturn dictators around the world. Sharp, and those that followed him, help us to understand what it means to apply pressure without using violence, and the ways in which this can be achieved – from sit-ins to mass protests. Other works provides inspiration to adherents of nonviolence through descriptive narratives of campaigns around the world from Russia to the United States to India and beyond. Critical lessons from the American Civil Rights movement and other successful campaigns for social change have illustrated the power of nonviolence in achieving these changes.

Many studies of nonviolence have emphasized the goal of delegitimizing one’s opponent or restricting an adversary’s use of power. Work on regime change in El Salvador and South Africa, for example, focuses our attention on the ability of civil resistance to impose costs on the state. Importantly, this ability is linked both to strategy choices of the resistance movement, and to the extent to which mass mobilization can be achieved.

Quite recently, there has been a shift in the study of nonviolence toward trying to understand its efficacy, that is, how and why civil resistance works. One study compares successful and failed nonviolent campaigns, showing that tactical innovation plays a role in determining which campaigns succeed. Indeed, the use of social media, such as twitter is presumed to have played a role in the recent successes in the Middle East. Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan’s recent book Why Civil Resistance Works compares the violent and nonviolent campaigns. They argue that nonviolent campaigns draw more participation and in doing so, are able to create a fairly stable base of supporters who are willing to impose costs on the state.

Strikingly, Chenoweth and Stephan find that nonviolent campaigns are twice as likely to succeed as violent ones. This runs counter to many people’s impression that resorting to violence is the more effective way to impose costs on the state.

This recent scholarship on the success of nonviolence had highlighted an important gap in our understanding of the efficacy of nonviolence in different contexts. The recent social revolutions in the Middle East have brought this issue to the forefront. Many of those movements had peaceful roots, but only some survived as large scale nonviolent campaigns.

Several central questions emerge from this:

First, the relative success of nonviolent campaigns appears to be limited, to some degree, to pro-democracy movements. Research shows that nonviolent campaigns are much less successful when focused on the issue of territorial control and secession. Few groups are able to secede in the contemporary international system, but the dominant strategy through which this is achieved is violent resistance. This is troubling because war over national self-determination has become the most common type of conflict in the international system in the past few 40 years. Cases such as Chechnya and the Tamils in Sri Lanka exemplify these disputes. There is also a great deal of potential future conflict over this same issue. Since the end of the Cold War, there has been a steady increase in the number of minority groups seeking greater self-determination over time.

Thus, we have some reasons to believe nonviolence works, but not particularly well for one of the more pressing challenges in the international system today. Why that is the case, and how it can be changed, is a critical question for the future.

A second question emerging from the evaluation of whether and how nonviolence works relates to the necessity of mass participation. Scholars and practitioners alike highlight the importance of mobilizing people in large numbers. Yet, we know little about the conditions under which this is likely to happen. The success of nonviolent campaigns hinges on achieving a high number of participants, and this can create a substantial problem of collective action. Moreover, many civil resistance movements are met with repression, which creates a strong disincentive for individual participation.

How do some campaigns overcome this? The ability to generate mass mobilization is likely to be influenced by a number of factors, such as the nature of the movement (be it regime change, pro-democracy, or separatist). The resources available to supporters, and support from actors outside the movement, such as kin living across borders and the international community, can also play a critical role in mobilization. Moreover, many successful campaigns for social change are inspired by charismatic leaders, such as Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and Mahatma Gandhi, and sustained by continual acts of courage and commitment by leaders such as Congressman Lewis.

Our understanding of how and why different factors contribute to the success of nonviolent resistance remains limited, despite the wealth of practical and normative work done in this area. This question should be the focus of sustained research, much in the way that we have endeavored to understand the outbreak and consequences of violent campaigns.

Finally, we need to integrate our increased understanding of civil war and social violence with an understanding of nonviolence. Studies that evaluate the effectiveness of nonviolence have largely been comparisons of their success and failure, or more recently whether violent or nonviolent campaigns are more effective. What is missing from this existing approach is that nearly all movements for political change involve elements of moderation as well as radicalization.

Let us return to the example of struggles for national self-determination. Even among the most conventional political struggles, such as the Jura movement in Switzerland, there were elements of strategic violence

Moreover, disputes rife with violent conflict, such as the Chechen movement, contain organizations that forge ahead to seek political change by eschewing violence. Indeed, many social movements appear to be engaging in both violent and nonviolent resistance in an effort to secure political change. At times, organizations within these movements change strategies – transitioning from freedom fighters to activists and vice versa.

If organizations seeking political change make strategic choices about whether to use violence or nonviolence or both, then we need a better understanding of when and why they chose a particular strategy, and why individuals choose to participate in one way or another. Part of the answer is likely to be related to what others are doing, especially since successful nonviolence requires mass participation. But there are likely to be other factors that influence the strategic choices that these organizations make, and these are likely to change over the trajectory of a campaign. Thus, understanding incentives for the use of both violence and nonviolence at both early and later stages of social upheaval is important.

These questions, and the answers we hope to find, have important implications for real world policy choices. Recent events have shown us that the international community can play a critical role in determining the success of civil resistance, but it is not necessarily a straight forward role. If we return to the issue of secession, we can see clearly how the international community is both empowered and critically limited. Secession is nearly impossible without support from the international community. The referendum on independence in Southern Sudan highlighted the power of people to choose their own political future, but this ability is predicated on international support. Many groups that aspire to statehood hold similar referenda, but with little consequence. Yet the international community cannot universally support secession. States want to retain their own territorial integrity, and minority groups want to exercise their rights to self-determination.

How the international community responds to this tension is important. It creates incentives for separatists to use particular strategies, and this can make violence or nonviolence more or less attractive as a means to social change. We can see this same dynamic illustrated in the response of the international community to the Arab Spring. There was explicit support given for the armed overthrow of Qaddafi. Yet, we failed to see large-scale intervention in the cases of nonviolent resistance. This contrast may very well create incentives for the use of violence.

These are but a few examples, from which it would be quite difficult to discern a pattern of influence, and even more difficult to create coherent policy. We need greater attention to what kind of incentives the international community creates for agents of social change. Thus, there is a critical challenge for scholars and policy-makers alike. If we want to promote the use of nonviolence, we need to sponsor and engage in sustained research on it, such as the ongoing work at here at PRIO. We need to explore the conditions under which it is likely to work, and reach towards an understanding of what actions the international community can take to make nonviolence more effective and consequently more attractive to people earnestly seeking social change.

Thank you.

Kathleen Cunningham is an Assistant professor in the Department of Government, University of Maryland, and a Research associate at the Centre for the Study of Civil War, PRIO.