There are really two types of Nobel Peace Prize Laureates—elites (or elite-led institutions) and ordinary people. Elite winners generally seem to be those that are trying to forge or preserve peace. But ordinary individuals tend to be troublemakers—those that are trying to use nonviolent action to upset the status quo to bring more justice to oppressed peoples.

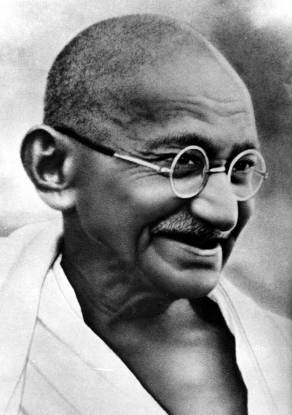

The 2014 laureates share much in common with Gandhi.

Photo: Wikipedia

After a couple years of elite-led institutions winning the prize (the European Union in 2012 and the UN-led mission to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons in 2013), this year the committee opted to celebrate and encourage the impact of two everyday troublemakers: Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai. In the committee’s justification of the award, they recognize Ms. Yousafzai’s courage, sacrifice, and continued activism inspiring girls and women to fight for their rights worldwide. They recognize Mr. Satyarthi’s use of nonviolent action in support of children in India as “maintaining Gandhi’s tradition.”

In fact, both of these laureates—and many others—share much in common with Gandhi. Like him, they are ordinary people who have devoted their lives and energies to giving voice to the oppressed. Like Gandhi, they do so with a fierce commitment to nonviolence—both because they believe in the principles of nonviolence but also because they believe in the power of nonviolent action in effecting real change. Like Gandhi, they both know that nonviolence isn’t for sissies—in fact, it requires incredible courage, discipline, and sacrifice (Malala in particular has endured a great deal of cynicism and alienation within her own country).

They are not alone. There is no doubt that Gandhi had a tremendous impact on the 20th century—not just on demonstrating the power of nonviolent conflict, but in challenging the prevailing myth in the international system that violence is the only effective way to confront brutality. In fact, a considerable number of Nobel Peace Prize laureates were directly inspired by Gandhi’s struggle, including the American Friends Service Committee (1947), Martin Luther King, Jr. (1964), Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan (1976), Lech Walesa (1983), Desmond Mpilo Tutu (1984), Aung San Suu Kyi (1991), Nelson Mandela (1993), Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo and Jose Ramos-Horta (1996), and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (2011), among others.

His legacy spread to Martin Luther King, Jr. through a decades-long interchange of African Americans who traveled between the southern United States and India in the early 20th century to learn about Gandhi, his teachings, and his strategies. Reverend James Lawson read Gandhi’s autobiography while serving a prison sentence for refusing to serve in the U.S. military during the Korean War. Once released, Rev. Lawson spent several years in India, studying Gandhi’s works and visiting with his followers at his ashram. When Rev. Lawson returned to the United States at the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, his teachings of Gandhi’s theory, strategy, and methods of nonviolent action convinced many in the Civil Rights movement (including Martin Luther King, Jr.) that mass civil resistance was the best way to fight back against segregation and Jim Crowism.

Gandhi’s legacy found its way (back) to South Africa during the anti-apartheid movement, during which black townships launched mass civil disobedience through boycotts against white businesses, protests, and the building of alternative political and economic institutions. Like Gandhi, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela both saw the power of withdrawing cooperation from an oppressive system, and seeking to construct a better one in its place.

And Gandhi’s legacy partially inspired Gulail and Saba Ismail, two sisters in Pakistan, to create an organization called Aware Girls—a NGO devoted to informing girls in Swat Valley about their education and reproductive rights. This has earned them death threats, of course, but it has allowed them to make a real impact—including on one of their mentees, Malala Yousafzai.

There are numerous ironies to this, of course. Most notably, Gandhi himself never won the Nobel Peace Prize, although he is clearly the one individual who had the greatest impact on the theory and practice of nonviolent action in the last 100 years. The second irony is that although Gandhi’s method of nonviolence spread throughout the world (and has seen great success in many places), his own struggle in India was only partially successful. He was never able to fully convince many religious nationalist groups of the utility of nonviolence, and the ultimate separation from the British empire was long and violent. Gandhi viewed it as a terrific failure and a horrible tragedy to see the bloody partition of the Indian subcontinent; his real hope was that Hindus and Muslims would find a way to coexist.

Thus, in a very real way, the Nobel Committee got it doubly right this year. Not only did they locate two wholly deserving peaceful troublemakers, but they did so in a way that reflected Gandhi’s own hopes that the diverse peoples within the subcontinent would make peace and thrive together. Gandhi’s century has come full circle, and it is certain that “The Missing Laureate” would be pleased.