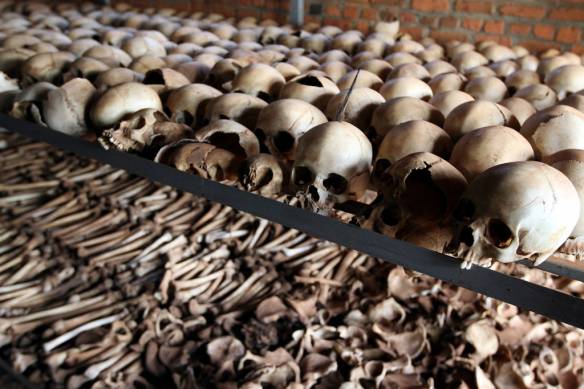

Photo: DFID, Tiggy Ridley, via Flickr

Reading “The Reign of ‘Terror” by Tomis Kapitan in the New York Times on October 19th, I was struck by the following passage:

…the rhetoric of “terror” has had these effects:

- It erases any incentive the public might have to understand the nature and origins of their grievances so that the possible legitimacy of their demands will not be raised.

- It deflects attention away from one’s own policies that might have contributed to their grievances.

- It repudiates any calls for negotiation.

- It obliterates the distinction between national liberation movements and fringe fanatics (for example, during the 1990s, the “terrorist” label was applied to Nelson Mandela and Timothy McVeigh alike);

- It paves the way for the use of force by making it easier for a government to exploit the fears of its citizens and ignore objections to the manner in which it responds to terrorist violence.

Now, this passage struck me because for a few years now I have been trying to deal with interesting labels that have the same effect on discussion of what took place during Rwanda in 1994 (e.g., “denier”, “denialism”, “trivialization” and “minimization”). As mentioned by Kapitan, the word terrorism ends conversation, it suspends thought, it prompts emotion, and then it facilitates all types of actions on the side of the accuser. The accused is kind of just caught there like a deer in the headlights and in the silence an audience builds up hostility that such a thing could happen. Similarly, using the phrase denier or denialism, and even more problematic (I will argue), trivializing and minimization, is generally not good for those of us that are interested in trying to systematically identify, evaluate and understand diverse phenomenon including – arrests, protests, torture, lynching, disappearances, conflict related rape, terrorism, targeted assassination, beating and mass killing. Indeed, individuals engaged in such efforts struggle a great deal to obtain information that is reliable, make evaluations that are decent and draw conclusions that logically follow from what we have seen. For example, such efforts and debates have informed discussions of casualty counts in Cambodia, Kosovo, Guatemala, recently Iraq and the Holocaust. Without a discussion of sources, biases, alternative estimation procedures, different interpretations, ranges of estimations and error, our understanding of these cases would have gone nowhere.

Read more at Political Violence @ a Glance, where the complete version of this post was published 24 October 2014.