Generally speaking, the global map of conflict is increasingly shaped by armed conflicts involving Muslims on one side or the other, or on both. Are Muslim countries particularly belligerent? Is the religion to blame?

Despite the numerous items of bad news delivered by the mass media on a daily basis, a global overview of armed conflict shows several positive trends. During most of the Cold War, there was an increase in the number of ongoing armed conflicts worldwide, but the number decreased sharply after the fall of the Berlin Wall. This trend is even stronger if we restrict our survey to conflicts large enough to be classified as wars (more than 1,000 combat-related deaths in a calendar year). Although the total number of conflicts varies year by year, the trend has been roughly stable since 2001. The number of combat-related deaths follows a jagged line over time, with peaks that have become consistently lower ever since World War II. On average, approximately 300,000 people died in war each year in the first decade after World War II. In the first decade of the 21st century, the corresponding number was approximately 44,000 per year, even though world population had more than doubled. During the last few years, the number of victims has risen once again, primarily due to the civil war in Syria. Even so, we are very far from a new Korea or a new Vietnam. Interstate wars occur very rarely; the wars still being fought are civil wars.

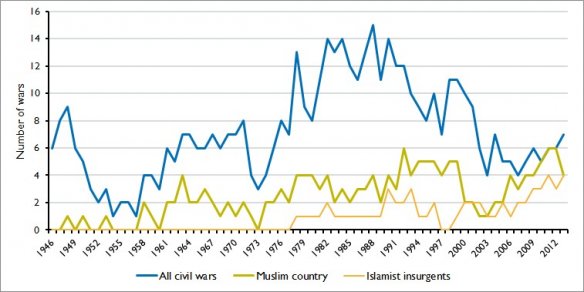

But what about the Muslim world? The graph below shows the number of civil wars worldwide, the number of civil wars in Muslim countries (defined as countries with a majority of Muslims), and the number of civil wars involving Islamist insurgents. During the early years of the Cold War, there was a certain rise in the number of civil wars in Muslim countries. However, this increase was not as clear and long-lasting as the rise in civil wars in the world as a whole. Immediately after the end of the Cold War, the number of civil wars in Muslim countries increased again, then it fell sharply, before it rose again after 2001 – although not to an unprecedented high level. The number of civil wars involving Islamist insurgents has increased sharply in the past 15 years.

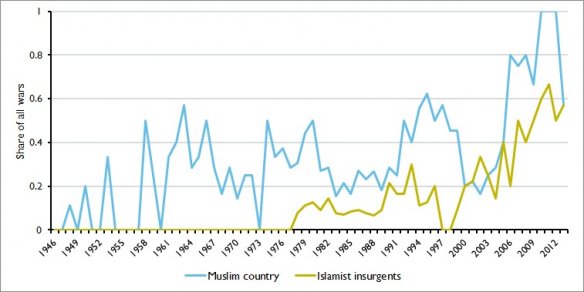

The picture changes if we look at the second graph, which shows the proportion of conflicts taking place in Muslim countries as well as conflicts that involve Islamist insurgents. Once again we see a certain increase in conflicts in Muslim countries in the early post-war period and then again immediately after the end of the Cold War. But the increase since 2001 has been far more dramatic: In 2011 and 2012, all civil wars worldwide were fought in Muslim countries.

Generally speaking, the number of civil wars being fought in Muslim countries has not increased sharply in recent years. But because the number of civil wars in other countries has decreased, the news media are becoming more and more dominated by conflicts involving Muslims.

In general, the picture is the same if we look at all internal conflicts, including those that cause fewer than 1,000 deaths in a year. But it is particularly clear in the case of the most serious wars. The proportion of conflicts where rebel groups have an Islamist orientation is also increasing strongly, and this has been the case right since the end of the Cold War. These Islamist rebel groups are particularly uncompromising in their approach to warfare, and this probably contributes to making these conflicts especially bloody and difficult to resolve.

While we worry, not unreasonably, about the terrorist threat in Europe, we should not forget that Muslim countries are the most affected by Islamist violence. As Mohammad Usman Rana so aptly put it in Aftenposten on 14 January, ‘Islam’s house is on fire’. This is not a ‘clash of civilizations’ between Islam and the West, but a ‘bloody internal Muslim battle over Muslims’ hearts and minds’.

How has this come about? One possible explanation is that the majority of these countries continue to suffer the effects of the arbitrary borders imposed during the colonial era. Territorial conflicts often take a long time to resolve. Another factor is the traditional strategic importance of the Middle East, both due to its position between East and West and its oil wealth. Several military interventions in recent years have replaced relatively stable dictatorships with unstable semi-democracies. The fact that the number of conflicts in Muslim countries has increased particularly sharply since 2001 may also indicate a counter-reaction from the Muslim world – not only against countries that intervene, but also against their supporters within the Muslim world.

Many strong critics of Islam consider it to be more violent than other religions. All religions, however, have elements of violence and of peace. The question is how religious and political actors emphasize these different elements. Both Islam and Christianity are proselytizing religions, and Samuel Huntington’s prediction of a war between civilizations highlighted the particular danger of a war between Christians and Muslims. However, the main picture today is one of a serious conflict within the Islamic regions, even though this conflict also has ripple effects in countries where Muslims do not form a majority.

The fact that the rest of the world has become more peaceful, while at the same time the Muslim world has moved in the opposite direction, may perhaps be attributed to the greater degree of political and economic change in non-Muslim countries, which has contributed to reducing the occurrence of violence both within and between them. Most Muslim countries lag behind other countries with regard to democracy and human rights, such as the rights of women. Many suffer from weak economic development, even though some have become extremely wealthy due to oil resources. Some are trapped in a ‘curse of natural resources’: high dependence on exports of raw materials. In recent decades we have experienced high oil prices, and many oil-rich countries, particularly in the Arab world, have had the wealth to fund rebel movements with the potential to destabilize regional rivals.

An analysis of conflicts in the Middle East that I published 10 years ago together with two colleagues concluded that religion was not a significant factor for explaining the frequency of conflicts. More important factors were the types of regimes, economic growth (or the lack of it), and ethnic dominance. But what if these factors are themselves influenced by religion? In that case religion would influence conflicts indirectly.

These circumstances are not impossible to change. Only a few decades ago, scholars debated seriously whether or not democracy was possible in Catholic countries. Perhaps lower oil prices, and the gradual transition to other forms of energy, will force changes in the Muslim world that may help to reduce the number of conflicts?

In the meantime, Muslim countries live with a higher average level of conflict than most others. For scholars it is important to find out more about why this is so. And for decision-makers, discerning the reasons for this higher level of conflict is a task of the highest priority, in order to help prevent the outbreak of new conflicts, reduce the danger of international escalation, and contribute to conflict resolution.

- This blog post is a slightly longer version of an article (‘Brannen i Islams hus’) published in Norwegian in daily Aftenposten on 12 March 2015.

- The post is based on Nils Petter Gleditsch & Ida Rudolfsen: ‘Are Muslim Countries More Warprone?‘ Conflict Trends Policy Brief 03/2015. Oslo: Peace Research Institute Oslo.

Evidence indicates the cause might be urbanization interacting with contract-poor economy, as Muslim-majority countries experienced higher-than-average urbanization rates in the 1980s and 1990s (see my article “Urban Poverty and Support for Islamist Terror: Survey Results from Muslims in Fourteen Countries,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 48, No. 1, February 2011). I have argued that the decline in violence elsewhere, within and between nations, is driven by the nations with contractualist economies, as these nations have no interest in fighting each other and common interests in global law and order (see my articles “Capitalist Development and Civil War,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 3 (September 2012) and “The Democratic Peace Unraveled: It’s the Economy,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 57, No. 1 (March 2013)).