Nearly five years since Tunisia’s revolution began to spread, the hopes and expectations of democracy have been replaced by despair and fear of what will follow.

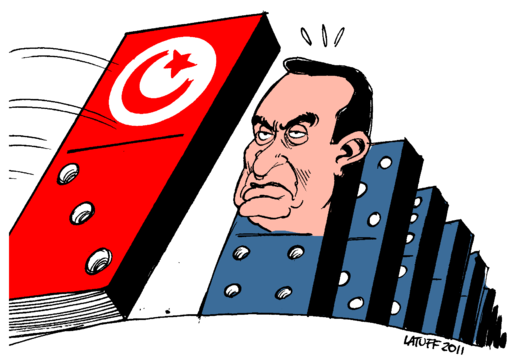

“In their despair over the current situation, some people are falling victim to the temptation to look back with nostalgia to the old regimes”. Hosni Mubarak facing the Tunisian domino effect. Carlos Latuff 2011.

This has been an important and proud autumn for Tunisia and the Tunisian people. Ever since the Chair of the Nobel Committee, Kaci Kullmann Five, announced in October that the Peace Prize had been awarded to the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet (and once everyone had discovered via Google that the Quartet was not in fact a group of jazz musicians) the “Tunisian Model” has quite rightly received much praise and attention. Both when announcing the Nobel Committee’s decision, and in her powerful speech at the award ceremony at Oslo’s City Hall on Thursday, Kullman Five highlighted the Quartet’s work to ensure that the long road leading to a liberal democracy had broad support among the Tunisian population. Accordingly, the committee also emphasized that the prize was intended as a “handshake” with the Tunisian population, and as “inspiration” for all other individuals and groups in the region who wish to work for democracy and peace – an inspiration of which they are no doubt in need.

For the bleak reality is that the optimistic melodies of the Quartet are being completely drowned out by the noise of barrel bombs, tanks and terrorism. In Syria the death toll continues to rise, and the situation on the ground is extremely complex. This complexity will not be lessened by the current escalation of the battle against Islamic State (IS). In Egypt, the military regime headed by General Sisi has fastened a new iron grip on Egyptian society. Most people following developments there are in agreement that Sisi’s Egypt is in many ways worse than Mubarak’s. The same bleak description applies to Libya, which since Gaddafi’s fall in 2011 has experienced almost total collapse. Yemen, like Libya and Syria, has become the scene of a regional proxy war, which has all the ingredients to become long-lasting and even bloodier. And even though neither Lebanon nor Jordan experienced major national uprisings in 2011, both countries are being dramatically affected by the consequences of the civil wars in Syria and Iraq. In other words, things may yet get worse. If one leaves Tunisia out of the picture, the entire Arab world has taken one step forward and three steps backwards. Both expert debates and newspapers are full of analyses and commentaries on why things went wrong.

In their despair over the current situation, some people are falling victim to the temptation to look back with nostalgia to the old regimes. Those with a tendency to be nostalgic about dictators admit that yes, those leaders tyrannized and oppressed their own populations, and imprisoned, tortured and killed people who were seen as critical of their regimes, but at least they kept the situation stable. Owing to the region’s indisputable geopolitical importance, this stability has great value to the West. Consequently silent acceptance of these autocratic regimes was in reality far more widespread than vociferous protest.

Associated with this longing for the stability provided by autocracy is the idea that a well-functioning Arab democracy is in itself a contradiction in terms. But is it really so simple? Is this region doomed to eternal autocracy and political oppression?

Many people object strongly to such an analysis. One such objector is Sheri Berman, professor of political science at Columbia University in New York. Berman reminds us that the processes of democratization in countries such as France, Italy, Germany and the United States were far from beds of roses. Rather these processes were marked by extreme turbulence, with major internal conflicts, reversals and detours, and not least large numbers of deaths. According to Berman, this was a natural part of the process and the same now applies to the Arab world. The issue is not that the new players in the region are incapable of being democratic. Rather, they are being dragged back under the surface by the legacy of decades of autocratic and oppressive government. Establishing and maintaining a stable, liberal democracy is a long, difficult and painful process.

If we apply a longer historical perspective, however, we see that it is far too early to pass any judgement on either the Arab Spring or the future of the Arab world. Simultaneously it becomes more difficult to point to Islam, ethnicity or ideology as factors to explain why the first act is so bleak. People in the Arab world of course have no less desire for freedom and democracy in the uncertain situation in which they are now living, rather quite the opposite. This is a drama in several acts, and we do not have the option of leaving during the interval. For although it is perhaps most comfortable to think of ourselves in Norway simply as members of the audience, the refugee crisis, for example, makes it clear that the situation is not so simple. The development of the region concerns us all directly. The Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet and Tunisia in general show that there is hope and a way forward, through dialogue and the inclusion of civil society.

The Quartet and their peers – both men and women – must be allowed to play out this drama over the space of several acts.

- This text was published in Norwegian in Dagsavisen 15 December 2015, available at Nye Meninger: ‘Et drama i flere akter‘.

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext