Photo: Flickr/Teymur Madjderey

The politics of rape denunciation is fast becoming the politics of lobbyists, vendors and military manufacturers seeking access to new customers and markets.

The recognition of wartime rape as a fundamental violation of international law has been a hard-fought victory. Ending rape and other forms of sexual violence in war ought to be a central aspiration of the international community. But the struggle against rape has attained a kind of moral currency, put to use by those lobbying for ‘lethal autonomous weapons’ (LAWs). And in doing so, the politics of rape denunciation is fast becoming the politics of lobbyists, vendors and military manufacturers seeking access to new customers and markets.

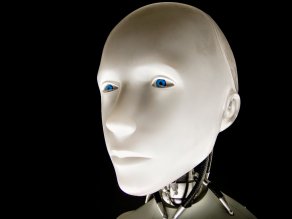

A recurrent argument within the debate surrounding ‘lethal autonomous weapons’ is the idea that taking humans out of the loop would make war more humane. And in particular, it would end the occurrence of rape. This ‘robots-don’t-rape’ argument is premised on the assumption that robots are better at keeping to the norms of war, and free from human inclinations towards lust and greed, panic and rage.

This equation of technological innovation with human progress is deeply problematic.

The instrumentalisation of the ‘Very Worst Sex Crimes’ is nothing new: governments have for a long time used the scourge of online child pornography to legitimate widespread censorship and surveillance in cyberspace.

But the claim also belongs to a broader category of arguments claiming that new military technology can create better wars because they are pre-programmed, remotely controlled, and ‘surgical’.

The argument that drones limit collateral damage and contribute to ‘humane warfare’ because they are surgically precise is by now familiar. Countless commentators argue that cyber-war is preferable to conventional war because it is presumed to make war less bloody. Following the same type of logic, autonomous robots are portrayed as the vehicles for perfect legal compliance and perfect soldiering, which in combination will produce ‘perfect combat’.

There are important factual inaccuracies to this line of argument. First of all, the 1998 definition of rape in international law, as codified in the Rome Statute for the International Criminal court is a broad one, according to which rape is not reducible to forcible penetration of women committed by men. Rather, rape occurs when:

“The perpetrator invaded the body of a person by conduct resulting in penetration, however slight, of any part of the body of the victim or of the perpetrator with a sexual organ, or of the anal or genital opening of the victim with any object or any other part of the body.”

The ‘robots don’t rape’ argument is based on misleading assumptions about the uses of rape in conflict. This conceptualization of rape is accompanied by an implicit understanding of motivation and rationale: that rapes in war are spontaneous and unplanned and thus a breach of discipline. Research has shown us that, contrary to widespread belief, sexual violence is not the male soldier’s appropriation of his ‘war dividend’; but is used strategically against civilians as a weapon of war.

The indiscipline argument can be turned on its head. If lethal autonomous weapons are programmed to kill, they may also be programmed to carry out other forms of violence, including rape. On account of possessing free will, a human soldier can refuse to accept an illegal command to rape. A robot cannot.

What happens when we accept the ‘robots-don’t-rape’ argument? We risk undermining hard-fought gender battles, reducing wartime rape to an issue of uncontrolled and uncontrollable male sexuality and penis-penetration of predominantly female victims. And we fail to recognise it primarily as an act of violence, which may or may not be deliberate, intentional, and programmed.

- This text was first published at Open Democracy, 1 November 2015.