In the early hours of the morning on 15 November, the Zimbabwean military placed President Mugabe under house arrest. The coup against one of the longest serving rulers in Africa appears to have been a reaction to Mugabe’s ouster of his vice-president Emmerson Mnangagwa, to pave the way for his wife as the successor to his rule.

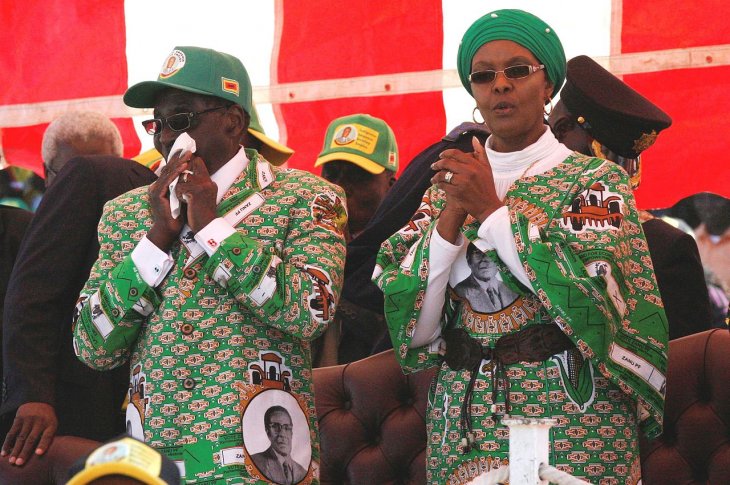

Robert and Grace Mugabe. Wikimedia Commons

Dictators are often deposed in military coups, and historically as many as 2/3 of all deposed dictators suffer this fate. The question now is: what kind of rule will Zimbabwe see after the fall of Mugabe? In a best-case scenario, this coup could be the beginning of the end of dictatorial rule in Zimbabwe.

Mugabe has ruled Zimbabwe with an iron fist since the independence in 1987. He has overseen a country with extreme corruption and economic mismanagement, with an inflation rate that has exceeded one billion percent. His government has also been responsible for atrocities such as the Ndebele massacres in the 1980s. If this coup is a return to power for his once loyal deputy Mnangagwa, what basis is there to hope for democratic reform?

The economist Paul Collier has suggested that military coups may be the best prospect for ending established authoritarian regimes and triggering transitions to democracy. This idea of beneficial coups can be seen in examples where the fall of a dictator has been followed by democratization, such as Portugal in 1974 and Mali in 1991.

By shaking up established institutions and powers, coups can provide opportunities for change. There is often substantial pressure for democratic reform in the wake of both successful and unsuccessful coups.

Since coup attempts increase the risk of future coups, promise of democratic reform can be a way to manage discontent and help provide stability. Moreover, the need for capital is often high after a successful coup, and the threat of cuts to aid has proven an effective way to extract promises of free and fair elections.

Still, in many cases coups do not lead to meaningful reforms and sometimes even precede change for the worse, such as the 1969 coup in Equatorial Guinea, unleashing large-scale political repression.

Yet studies of coups and democratization yield ambiguous results. Many studies conclude that coups in autocratic regimes tend to increase prospects for democratization compared to non-coup cases, while other studies find that the most common outcome of a coup is a new autocratic regime, often with increased repression.

This uncertainty reflects the wide variation in post-coup trajectories, and it is likely that other factors play a part in shaping the prospects for subsequent democratization. Our research examines how the political consequences of coups depend on social mobilization and opposition. Despite the fact that coups often reinforce authoritarianism, we find much better prospects for democratization after coups in countries with higher social mobilization.

Both successful and failed coups create uncertainty over political control, and the first response of dictators is often to establish control through the strengthening of autocratic institutions and increased repression. However, a larger mobilized opposition makes it difficult to ride out a storm through repression alone, and increases the incentives for implementing democratic reform. Greater social mobilization increases the power of non-elites and heightens the prospects for successful challenges to dictatorship. As such, implementing democratic reform can be one way to manage pressure from below, and gain some control over the situation. Besides, coups tend to foster power struggles within the regime, where rival elites may use promises of democratic reform to try to gather popular support, and as such improve their own position.

Whether the coup in Zimbabwe will lead to genuine democratization depends on the coup makers and intra-elite dynamics, but social mobilization can shape and constrain their incentives. In this respect, we find the increased organized opposition and demonstrations for reform over recent years an encouraging sign of hope that this coup can be a major step toward a democratic transition in Zimbabwe.