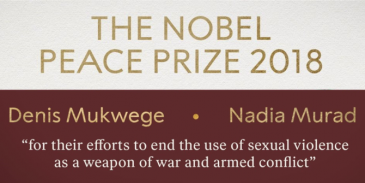

The choice to award the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize to Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad is both timely and wise. The two Nobel laureates embody different dimensions of conflict-related sexual violence. Further, the prize comes at a time when we mark the one-year anniversary of the #metoo movement, when trust in international bodies and agreements is on the decline, and when violent extremism is on the rise.

While this Nobel Peace Prize is by no means a #metoo prize, there are features of the movement that are compatible with the fight against conflict-related sexual violence.

While this Nobel Peace Prize is by no means a #metoo prize, there are features of the movement that are compatible with the fight against conflict-related sexual violence.

The #metoo movement has moved the conversation about sexual abuse and harassment from a focus on how to improve protection and mitigate effects on victims, to a focus on the men, male cultures and organizations which enable sexual harassment and abuse.

The efforts to move the stigma away from victims to the perpetrators has been epitomized by the image of filmmaker Harvey Weinstein in handcuffs on his way to trial, and the recent sentencing of Jean-Claude Arnault who caused a public scandal for the Swedish Academy which awards the Noble Prize for literature.

In the efforts to combat conflict-related sexual violence, we have seen a similar movement: from focusing on the protection of victims to the prevention of people becoming perpetrators. Clearly, protecting victims is important, but the problem with conflict-related sexual violence is, primarily, that people commit these crimes. It is therefore wrong to call this a women’s prize or claim that it is related to women’s issues. If anything, this is a man’s issue; without the perpetrators there would be no crime, and the perpetrators are far too often men.

Denis Mukwege has articulated this problem and has called for stronger male engagement against conflict-related sexual violence. Further, he is himself a symbol of male engagement against conflict-related sexual violence through his decades-long work as a gynaecologist at the Panzi Hospital in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

I have myself interviewed a number of women who were subject to conflict-related sexual violence, and in all their narratives about male sexual violence runs a parallel story of a male hero who may have protected, mitigated or helped a female victim out of an abusive situation. This year’s award is a call to these men, these counter voices and all engagement against abusive male cultures, which have been part of Denis Mukwege’s recent public statements. In these efforts, the 2018 Noble Peace Prize and the #metoo movement have compatible aims.

The current international mood is one of increased distrust and disbelief in international commitments and organizations. This change in political rhetoric is a direct threat to the international engagement against conflict-related sexual violence. One of the important achievements in combatting conflict-related sexual violence has been in the fight against impunity. There has been a strong international consensus (with a few noteworthy exceptions) that conflict-related sexual violence must have consequences for perpetrators and their leaders.

International criminal prosecution of conflict-related sexual violence has been part of several ad hoc tribunals and is part of the Rome Statutes of the permanent International Criminal Court (ICC). But, as in times of peace and in national courts, sexual violence cases are hard to prove. In international courts the legal processes are long, often lasting for years, and very few people are convicted. In the ad hoc international tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), for instance, about half of the 161 indictments included charges of sexual violence, but only 32 individuals have been convicted. Still, these are 32 people who would not have been convicted had impunity still been the norm.

When South Africa was threatening to withdraw from the ICC in 2015, Denis Mukwege issued a statement about what this could entail, warning that “to weaken the ICC is to vote in favour of impunity, opening the door to more violence.”

In order for these criminal mechanisms to be effective in their efforts to combat impunity, it is imperative that survivor victims testify and tell their stories. Nadia Murad is therefore a crucial voice, along with many others. By hearing the stories and knowing the details, guilt and responsibility can be established. Furthermore, by voicing these experiences, conflict-related sexual violence becomes part of new grand narratives of war; they are not relegated to side stories, private consequences or health issues. They become part of the political understanding of armed conflict.

In the latest report to the United Nations Security Council from 23 March 2018 on conflict-related sexual violence, the Secretary General expresses a renewed and deep concern over the use of sexual violence by violent extremist groups. The report documents that sexual violence is used as a recruitment strategy to extremist groups; it is used as a way to terrorize populations and make them flee; and forced marriages, a euphemism for sexual violence, are used strategically against targeted individuals and groups for intelligence purposes.

In addition, sexual violence is part of conservative sexual ideologies against women and sexual minorities, and it is directly ordered in military manuals to manifest these conservative aims. ISIL and Boko Haram’s use of sexual violence against young girls are examples of this new and intensified use of sexual violence. Nadia Murad and her experience as a sexual slave to ISIL demonstrate all too clearly that despite intensified efforts to combat conflict-related sexual violence, there is still a long way to go. Now, as a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, her work will be even more important than it already was, and her voice will give courage to others who can come forward to tell and testify so that appropriate guilt and consequence can follow.

Conflict-related sexual violence is a societal problem and a military weapon. Committing acts of sexual violence is cheap and has detrimental effects, short term and long term, for survivors and victims. But, sexual violence is not just violence; these are also reproductive acts, sometimes by accident and sometimes with that goal in view. These children, conceived through violence, have been overlooked and understudied and are in dire need of our attention, care and engagement. Here is a challenge for the engaged international community combatting these crimes in the years to come.

The fight against conflict-related sexual violence takes many forms and the Nobel Peace Prize laureates Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad are exceptionally worthy of the prize for their courage and commitment in different ways. Let us hope that the acknowledgment of their work will further renew efforts in the fight against this particular form of violence, and help us to create better grounds for peace in the future.

- This text is also posted at blog of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.

The committee likes to get pull from popular persons or causes, but could not give the prize to MeToo for reasons I explained in Norway’s main daily, Aftenposten. It is interesting to see the committee in two consecutive years be at least within the themes of Nobel´s intended prize – to me it starts to look like a new policy, a new will to take Nobel´s intention seriously. The committee may have taken guidance from my article (in Norwegian)

https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/debatt/i/kaO9Kv/Kan-Nobels-fredspris-gis-til-Metoo-Arbeider-et-knippe-hashtags-organisert-og-malbevisst-mot-krig–Fredrik-S-Heffermehl