The question of what constitutes the “good citizen” has received renewed interest in Western Europe in connection with increasing pressure on the welfare state, concerns over migration-related diversity, and growing anxiety about a crisis of democracy. In a recently published article, ‘The “good citizen”: asserting and contesting norms of participation and belonging in Oslo’, we draw on data from fifty in-depth interviews and six focus group discussions with residents of Oslo to study the impact of the normative public debate on citizenship on everyday perceptions of good citizenship.

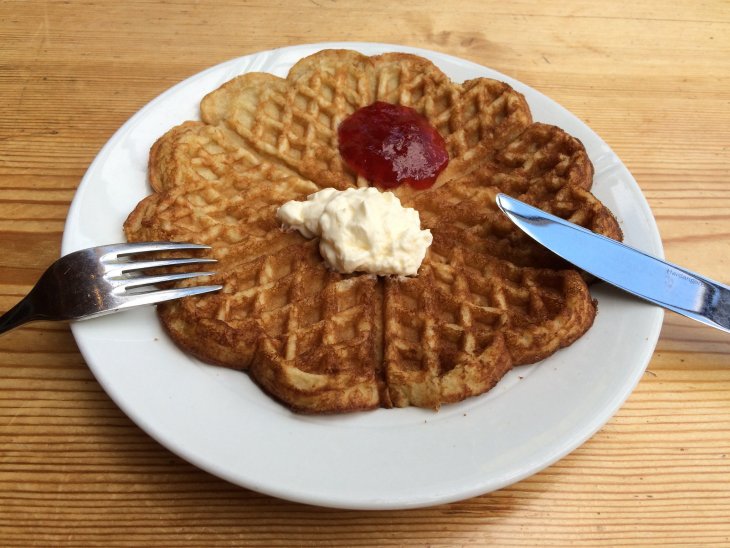

A typical example of what some think of as “active citizenship”: making waffles for school fundraisers. Photo: Tresting via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

How, and with what implications, do ordinary residents of Oslo relate to (often implicit) norms about the ideal-type ‘good citizen’? In our research we find that the normative public debate on good citizenship affects how people think about civic participation and belonging. An ideal-type ‘good citizen’ emerges in our data, which is an active citizen in the sense of being employed, taking care of family members, and being engaged in volunteer activities in Norway. Research participants judge their own and others’ societal contributions against this ideal-type. The result is often a sense of falling short, at times relating to not having the time or resources during certain life phases or when consuming life events occur unexpectedly. Yet the ideal-type ‘good citizen’ is not only asserted; this norm is simultaneously contested for the narrow ways in which it is commonly defined. Our research participants challenge underlying perceptions about where the ‘good citizen’ participates and to what collective(s) he or she can belong.

We will share three insights: First, research participants challenge the socially constructed divide between private and public life, which dominant norms of good citizenship rest on. They place their civic engagement in the private, and not just in the public, realm of human interactions. They are often eager to extend the public civic-political realm by defining everyday interactions and practices as civic engagement. This is related to their concern about the formalization of civic engagement, fearing that it will lead to more feelings of exclusion for those who do not have the same access to or ease of expression in formal arenas. A public-civic realm created through formalization and “professionalization” is never neutral and disadvantages particular groups in society. Our research shows that these groups could be migrants, but also the elderly or those experiencing various forms of crisis at a particular point in life.

Second, the matter of where the good citizen acts is closely related to understandings of “the collective”, and poses the question: To what extent can certain forms of participation be considered civic engagement when they benefit a smaller group within the larger society? A point of contention here relates to the idea that proper civic engagement only exists when one benefits others beyond one’s “own group”, when one works for the larger, national, community. This is a problematic idea, not least because this rule does not always apply in the same way for all citizens. In our study, we learned that while contributions to specific arenas or groups – such as making waffles at the local football club – are understood as larger societal contributions, contributions in other arenas – such as volunteering at church or in the mosque, or promoting Tamil dance through an organisation – are not. Our study underscores the need to recognize the dynamic and potentially inclusive nature of national communities, as these are co-produced in local neighbourhoods in cities like Oslo. We find that across different spaces of participation in Oslo residents’ everyday lives, a range of scales of belonging, including the national, are relevant and are being actively contributed to.

Third, while the civic participation discourse in Norway is often placed within debates on integration, diversity and social cohesion, all kinds of residents of Oslo meet the image of the ideal-type ‘good citizen’ in their daily lives: The pensioner who laments not being heard or being asked for her opinions about anything else but old age; the woman who cares for her sick child and has to admit to herself and others that she cannot maintain her active public role while managing the care, worry and sorrow in her household; and the father who may talk to colleagues about waffle baking at his daughter’s football tournament but will choose not to mention his activities in the local church. All these people struggle with the discourse on the ‘good citizen’ in their daily lives.

Because norms of participation and belonging as a ‘good citizen’ do not always align with the lived realities of Oslo residents, we call for a reconceptualization of the ‘good citizen’ in normative terms. Differently positioned individuals will all benefit from a more inclusive conceptualization of good citizenship: one that acknowledges present-day spaces of participation as both public and private, and that recognizes scales of belonging that contribute to a range of collectives, within and beyond nation-state borders.

Such a reconceptualization of norms of good citizenship, meanwhile, depends on both top-down nation-state efforts and bottom-up citizen acts of redefining. The current political context of polarization and anti-immigration rhetoric may not appear particularly malleable to such a redefinition process. However, our research points to shared experiences among Oslo residents – across migrant and non-migrant backgrounds – where the prevailing norm of “good citizenship” falls short of recognizing much ongoing civic engagement and societal contributions. Redefining the good citizen holds potential not just for making better use of these contributions but also for highlighting the many shared experiences of everyday life and active citizenship in Oslo.