Erik Rinde (1919–1994), a portrait written by Lars Even Andersen

The Norwegian version is available here (.pdf).

A family with traditions

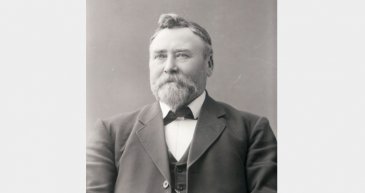

Erik’s paternal grandfather was Peder Eilertsen Rinde (1844–1937). Peder served as mayor of the Skåtøy and Sannidal municipalities in lower Telemark. As the owner of several large rural estates, he identified strongly with Søren Jaabæk’s Bondevennerne (lit. ‘The Friends of the Peasants’), a rural political movement aligned with the liberal opposition. He represented the Liberal Party (Venstre, lit. ‘Left’) in the Storting (the Norwegian parliament) almost consecutively from 1877 to 1918. He was also a shipowner and timber trader.

Erik’s grandfather Peder Rinde (1844-1937). Photo: Archive of the Norwegian Parliament

Peder Rinde was one of the leading figures in the group backing Johan Sverdrup prior to the introduction of parliamentarianism in Norway in 1884, and was an active member of the organized rifle corps that was formed to support the radicalization of the Storting. His conduct during the power struggle between the king and parliament during the 1880s created the impression among those loyal to the government and monarchy that Rinde was a dangerous revolutionary. For many people, the fact that he appeared several times in the company of Norway’s most prominent radical agitator, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, confirmed this impression. Rinde was also a member of Norway’s first parliamentary investigative committee, the ‘Midnight Commission’, which investigated (without coming to any conclusions) the extent to which the Swedish-Norwegian king had planned to use military means against the Norwegian parliament in connection with the constitutional disputes in 1884 and 1893.

In the final years of the 19th century, however, Rinde marked himself out as a strong opponent of the militarization that was strongly favoured by many activists, whether they were for or against abolishing the Union with Sweden.

Peder’s son Sigurd Rinde was born in 1889. As a young man Sigurd became general manager of Handelsbanken in Trondheim, but later founded his own industrial group, the Norsk Elektrokemisk Aktieselskab (NEA). In the years leading up to World War II, NEA acquired several local businesses in the power-generating and wood-processing sectors, and when peace came in 1945, the Rinde group included Trælandsfos, Holmen-Hellefos and Vafos Brug, two power plants (Dalsfos and Tveitereidfos), and several large farms and forests in the areas around Kragerø and Drangedal.

Rinde had bought several of these companies during the war, when they were far from risk-free investments. Some of the facilities had to be mothballed for long periods because the Germans confiscated the coal that the facilities needed for paper production. A chronic lack of spare parts also caused constant technical problems and frequent halts in production. On other occasions the plants were targeted by saboteurs, for example when the authorities decided that the paper produced by the plants should be used for German propaganda newspapers (some have also suggested that the Rinde family assisted with efforts to sabotage their own businesses). It was clear that these investments would not be profitable in the short term. At the same time, it turned out that Rinde had a good nose for a strategic investment, as his investments started to make good returns as soon as peace was declared and the situation began to return to normal.

The ship Sigurd Rinde. Photo: sjohistorie.no

Starting in 1948, Sigurd Rinde expanded into shipowning, and at its peak his shipowning business operated six custom-built vessels. These ships enabled the group to control the whole value chain for wood pulp, from production to delivery to the end-users, who were often located in distant parts of the globe.

The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 initially caused great uncertainty about the market for wood pulp. It soon became apparent, however, that the tense international situation was a goldmine for Sigurd Rinde. The whole world was stockpiling commodities, and wood pulp and paper were no exception. Prices rose to unprecedented levels, and Rinde reaped enormous profits in his dual roles as manufacturer and exporter. In 1951, for example, the Holmen-Hellefos plant alone generated pre-tax profits of NOK 12 million – an unheard of amount at the time.

These profits would eventually make a valuable contribution to supporting innovative social science research environments in Norway. Among other things, they financed the construction of the building close to Frogner Park that ever since 1960 has been home to the Institute for Social Research.

No. 31 Munthes gate

The Institute for Social Research (Institutt for samfunnsforskning, ISF) was founded on 9 February 1950. For the first 10 years it was located at No. 4 Arbiens gate, but in 1960 the institute moved to its purpose-built brick building at No. 31 Munthes gate, where it has been located ever since.

The developer and owner of the new building was Erik Rinde’s father, Sigurd Rinde, and the building remained in the hands of the Rinde family until ISF bought it in 1992. A slightly awkward situation arose when Erik Rinde, who was both chair of the ISF board and owner of the building, had to negotiate the sale with himself. The situation was resolved in all parties’ best interests, however, and one of the terms of the agreement was Rinde would keep his office in return for a peppercorn rent. Naturally enough that office is now the director’s office, currently occupied by Tanja Storsul.

The entrance to No. 31 Munthes gate. Photo: The Institute for Social Research

Phase 2 of the building project, comprising the north-east section of the building, was completed in 1980. The developer for the new part of the building was ISF, as represented by its then-director, Ted Hanisch. At the time, the situation was that the Institute for Applied Sociological Research (INAS), which had been spun off from ISF in 1966, and which was later merged with a couple of other research organizations to form the Norwegian Institute for Research into Childhood, Welfare and Ageing (NOVA), had ended up on the University of Oslo campus at Blindern under the directorship of Nathalie Rogoff Ramsøy. INAS was finding its premises increasingly cramped, however, and reached an agreement with ISF to move into the new extension once it was completed. Initially the building work was funded by loans secured on ISF’s founding capital, but soon after the work was completed the building was purchased by the Norwegian Directorate of Public Construction and Property (Statsbygg), which had suddenly identified some spare funds towards the end of its financial year. It was only in the 2000s that ISF was able to buy back Phase 2 from Statsbygg. At that time, NOVA was still occupying the premises. NOVA moved out in 2014, however, when it became part of Oslo and Akershus University College (now Oslo Metropolitan University or OsloMet).

The building was designed by the architects Trond Eliassen, Birger Lambertz-Nilssen, and Molle and Per Cappelen. The following information is inscribed on a plaque, which was installed at the entrance to ISF in connection with the 75th anniversary of the Oslo Architects’ Association in 1981:

Erik Rinde was one of the pioneers of social science research in Norway, perhaps even the most important. Many people looked up to him, which was natural enough, also given that he was the owner of the building where ISF was located. Rinde enjoyed great respect both within ISF itself and more generally within the social sciences in Norway and abroad.

Erik Rinde and social sciences

As we have seen, Rinde came from an industrialist family, which not only owned wood-processing businesses but also controlled the whole value chain. It might seem surprising that someone from this background – the commercial private sector – would become a pioneer in such a different area as social science. Nonetheless, despite the Rinde family’s industrial focus, members of the family had always had other interests. As a member of parliament, Erik Rinde’s grandfather, Peder Rinde, for example, had a long and distinguished track record of involvement in social and peace-related issues.

In the following, I will first describe Erik Rinde’s life and achievements in relation to Norwegian social sciences in general and the Institute for Social Research in particular. I will then discuss his importance for peace research.

Erik Rinde was born in 1919. He managed to attend lectures on sociology at the London School of Economics before the war, so his interest in the subject was already established at that time.

Rinde also studied law, earning an LL.M. from the University of Oslo in 1943, shortly before the university was closed down on 30 November.

The 1945 peace brought new ideas and visions for a new society. The nation was to be rebuilt, in ways that were new and better. Central figures were the philosophers Arne Næss and Harald Ofstad, as well as the lawyer Vilhelm Aubert, the political scientist Christian Bay, the psychologist Harriet Holter and a cluster of other academics in the early stages of their careers. They wanted to advance Norwegian social science research, in order to foster the creation of a new Norway. Sociology was to be a scholarly tool for these practical endeavours. The group had held more-or-less secret discussion meetings during the war and had become a close-knit circle.

Attitudes among the group’s members about strategies for resisting the German occupation had differed widely. Both Aubert and Næss, for example, had been members of XU, a clandestine intelligence organization. At the age of just 22, Aubert had become XU’s head courier, reporting directly to the Norwegian High Command in London and risking his life on several occasions. Others, including Harald Ofstad, held fast to their pacifist convictions and wanted the post-war trials to be conducted as leniently as possible. We can also well imagine that the “scholarly coordination” of the group was made more difficult by the fact that its members came from a broad range of disciplines. On the other hand, a heterogenous group will often be the best equipped to shed light on relevant topics from several different perspectives, applying them to identify the best possible solutions. This is why diversity among the staff is a strategic objective of most social science research environments. Arne Næss and his compatriots undoubtedly understood this, and thus deliberately cultivated their differences.

Erik Rinde came into contact with Næss’s circle in the summer of 1945, and quickly became interested in its work on specific sociological issues. At that time, Rinde had an office at No. 4 Grev Wedels Plass. Over the following years the circle, which the group had now dubbed the Philosophical Club, regularly held evening meetings at Rinde’s home in Makrellbekken, a suburb north-west of the city centre. Their wartime experiences were fundamental to the circle’s ideas, and Rinde was instrumental in steering the philosophical discussion towards specific societal challenges:

How can we know X and Y? What should we do now to create a better society? What must be developed, and in what way can scholarly research become a part of general cultural values?

These evening meetings began Rinde’s role as a practical facilitator and entrepreneurial organizer of research for Næss’s circle. In particular, Rinde and Aubert developed a life-long loyal friendship. Aubert would become one of ISF’s first board members and researchers, remaining there until his death in 1988.

In 1947, Erik Rinde obtained NOK 15,000 from his father. Among other things, the money was to be used to pursue plans for an institute for social science research, as had been proposed even before the war in a report by the University of Oslo’s strategic committee. This was the Rinde family’s first financial contribution to the broad field of social sciences, which was envisaged as being conducted in close association with the university. A young student, Stein Rokkan (1921–79), who would later become one of the most-cited Norwegian social scientists in international research literature, was assigned the task of awakening public interest in sociological studies and thus securing the status of the field in Norwegian academic life.

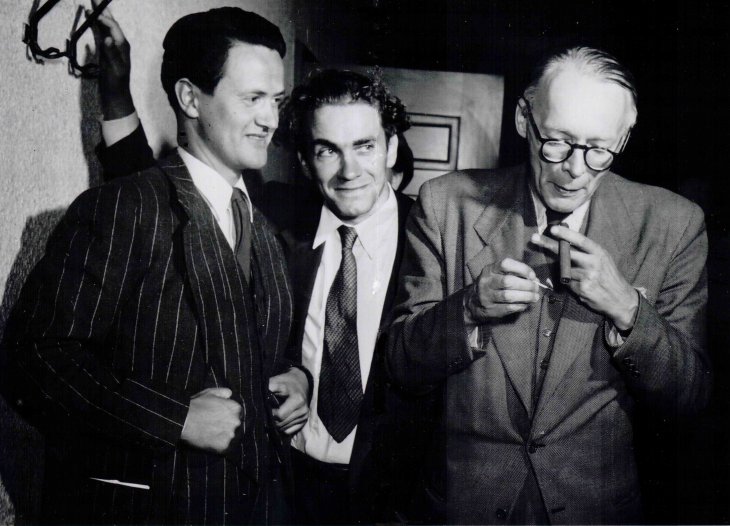

Erik Rinde, Stein Rokkan and Alf Sommerfeldt in 1950. Photo: The Institute for Social Research

Norwegian researchers looked to the United States, where social sciences were most advanced, for inspiration. Aubert estimated that in 1950, at least 10 American universities had faculties of social sciences. In 1947–48, both Aubert and Rinde had held research fellowships at Columbia University in New York, at that time considered the world leader in the relatively new disciplines.

In addition, there were several visits by guest researchers from Columbia in 1948–50, all funded by the Rinde family. Of these, we should mention in particular Professor Paul Felix Lazarsfeld (1901–76). Lazarsfeld is considered the founder of modern empirical sociology. He had been heavily involved with the social democratic movement in Vienna before he emigrated to the United States in 1933. Lazarsfeld succumbed to the temptation of a six-month fellowship in Oslo because he saw the ambition for a centrally-planned economy that was fundamental to the post-war reconstruction of Norway under democratic government, as an incredibly interesting socio-economic experiment, which he was keen to observe at close hand. Lazarsfeld lent important assistance to the research milieu in Oslo; although his visit did not give rise to much in terms of specific research outcomes, it was highly significant for the continued vitality of the environment which in time would become ISF.

In autumn 1948, Rokkan and Næss spent time in Paris in connection with an assignment for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Rinde and Lazarsfeld paid them a visit, with the aim of obtaining UNESCO’s support to establish the International Sociological Association (ISA) and the International Political Science Association (IPSA). As a first stage, they wanted to arrange a joint congress in Zurich in 1950. Rinde stayed in a luxury hotel and is reported to have been considered snobbish, but the visit proved a success, as UNESCO resolved to give their application its full support. In his efforts with UNESCO, Rinde obtained useful assistance from the Norwegian sociologist Arvid Brodersen (1904–96). During the war Brodersen had played a key role as a contact between the Norwegian resistance and German officers opposed to Nazism, and now headed UNESCO’s department of sociology. Accordingly, with UNESCO’s support Rinde founded the International Sociological Association in 1949, serving as its secretary general for the first four years, with ISF acting as secretariat. Rinde organized the first International Sociological Congress in Oslo in September 1949, while the International Sociological Association’s first World Congress was held in Zurich on 4–9 September 1950, with more than 120 delegates from 30 countries.

The Institute for Social Research was formally established in an office building in Arbiens gate on 9 February 1950. Stein Rokkan was the first director, but Rinde took over the post when Rokkan moved to the United States in autumn 1954.

At first, Rinde’s family was an important financial backer for the institute. Sigurd Rinde was a staunch supporter, providing founding capital of NOK 200,000 and a further NOK 500,000 two years later. Thereafter he provided operational funding of NOK 100,000 per annum. In addition to these funds, the institute soon managed to obtain support from the Ford Foundation. As time went on, the Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities (NAVF), which was founded in 1949 and was one of the precursors to today’s Research Council of Norway, would also emerge as an important funder.

It was essential to Erik Rinde that the institute included researchers who represented a broad spectrum of disciplines: lawyers, economists, psychologists, philosophers and, of course, sociologists. We also see traces of Rinde’s background in industry. In an interview with the Norwegian daily Aftenposten on 27 February 1954, he expressed the hope that the institute’s activities could be directed towards industrial research, “intensive studies of well-being and efficiency in industrial organizations” to “serve the needs of the state and commerce”.

We will return below to the founding of PRIO, which took place in and around 1959.

Rinde and Aubert felt that sociology was generally neglected in Norway at this time. This was despite the fact that the University of Oslo’s Department of Sociology had been founded in 1950 under the leadership of Professor Sverre Holm. For very many years, however, Holm was the only sociology professor in Norway, and his approach attracted varying degrees of enthusiasm among ISF researchers. Accordingly, Rinde and co. took the initiative to establish the Institute for Applied Sociological Research – INAS – in 1966 (1).

Next was the Psychoanalytic Institute, which was founded in 1967 with Harriet Holter’s husband Peder as its general manager. The objective was to “conduct research and train psychoanalysts”. At that time, psychology was seen as a basic discipline in the social sciences, far more so than is the case today, and Rinde was of course involved and contributed funds to the founding of this institute as well.

Despite the researchers’ periodic criticisms of Professor Holm, and the fact that in general their interests lay more in applied research (as was usual in the research institute sector), it was both natural and strategically desirable for ISF to cooperate closely with the University of Oslo. Similarly, both the Institute for Applied Sociological Research and the Psychoanalytic Institute, although they were autonomous research institutes, were established with a view to such cooperation. For reasons connected with organizational culture, it proved difficult to achieve strategic cooperation agreements with the university at an institutional level, but at an individual level there was always a lot of contact, especially when it came to teaching capacity. The connection was enhanced by a ‘revolving door’ between ISF and the university – many researchers at ISF had come from positions at the university, while others moved from ISF to such positions, and some also worked simultaneously part-time at both.

As time went on, Rinde moved away from actual research, focusing more on management and leadership, roles that he mastered very well. Rinde does not seem to have contributed to scholarship after the 1950s. He never completed a doctorate. In contrast, the roles of director and board member, where it was necessary to adopt a more strategic perspective, came naturally to him. This was how he could best complement Aubert, Næss and Rokkan, among others, on their paths to scholarly stardom.

Even so; precisely that fact that Rinde himself did not have a long list of publications, in some ways served as an advantage, as it made him independent of different scholarly trends and interests. He was an exponent of a pure, genuine interest in the field, without any personal territory to defend.

The family’s annual funding contributions continued until Sigurd Rinde’s death in 1972. At that point, the future of ISF became very uncertain. Erik Rinde resigned as director, and instead joined the institute’s board. Willy Martinussen and William Lafferty were employed as the leadership team, with Ted Hanisch (born 1947) as institute secretary.

Fortunately, ISF obtained government funding in 1975. At that time, Ingrid Eide was state secretary in the Ministry of Education and Church Affairs in the Bratteli government, and was no doubt very helpful in securing a stable flow of funds for the institute at a time of critical need.

In addition to this core funding, the institute was of course dependent on ongoing project funding to pay its researchers’ salaries. Ted Hanisch took over as director in 1976 and lay the groundwork for a transition to a project-based business model. NAVF was an important source of project funding. The institute’s researchers had good contacts and friends there, among them Mari Holmboe Ruge, who had been one of PRIO’s founders in 1959, and served as secretary of the NAVF’s Social Science Council for ten years from 1971.

In the same year, Rinde was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Oslo. No doubt this was not based on scholarly merit in the conventional sense, but rather a recognition of his contribution to the advancement of social sciences in Norway, both financially and as a research entrepreneur. Rinde was also awarded the Grand Cross of St. Olaf for his achievements.

Some years later, in 1986, Hanisch took a leave of absence from ISF to serve as a state secretary in Gro Harlem Brundtland’s government. Vilhelm Aubert then contacted Helga Hernes (born 1938) and Fredrik Engelstad (born 1944), and suggested that in the interim Hernes and Engelstad could run the institute together. Hernes was appointed research director, while Engelstad took on most of the managerial responsibility. Hanisch did not return to ISF after his term as a state secretary. Instead he became director of the newly established Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO), and Engelstad was appointed permanently as institute director. The position of director was not converted to a fixed-term post until Engelstad retired, 21 years later.

The most important reforms introduced by Engelstad involved a transition from a flat to a hierarchical structure, and setting an operational goal of making enough profit to build up a capital fund. Reforms were also made in the area of human resources. Previously only administrative employees had had employment contracts, while academic staff had had ‘membership’. In 1986, however, the researchers became employees. By now the institute’s operations were entirely project-based, and funding was obviously a precondition for the employment of new staff.

As a board member whose background lay in the for-profit industrial sector, Rinde no doubt appreciated this more professional approach. At the same time, the transition to a project-based organization meant that the institute became even more involved in applied research. In fact, ever since the 1970s this trend towards applied research had meant that the more theoretically-oriented Rinde had become more distanced from the institute’s tactical research orientation.

As time went on, Rinde took more of a backseat role at ISF. In his later years he was involved only to a limited extent in research activities, and only rarely ate lunch with the rest of the staff. For most of the younger researchers, Rinde gradually became an éminence grise. Nonetheless, some researchers often met up with him to exchange views in one-to-one discussions. Geir Høgsnes was one of these. Høgsnes worked at the institute for almost two decades, conducting research in economic sociology, a field in which Rinde was no doubt particularly interested, given his professional background. In addition, the institute secretary, Karin Sunde, had a close working relationship with Rinde. Sunde had been at ISF almost since it was founded, and she and Rinde were always on the same wavelength.

Rinde’s colleagues at ISF generally did not know much about what other irons Rinde had in the fire during his last years there. Most of the work he conducted from this office involved buying up companies, restructuring them, and selling them again at a profit.

As a person, Erik Rinde is described during this period as entirely amiable, and with a great passion for the social sciences, but at the same time correct and professional to an extreme. He spoke rarely or never to his colleagues about their families or other topics of a personal nature, and was not the type of person one would go to for personal advice.

Rinde remained a member of ISF’s board right up until his death. For the last six years, after Aubert’s death, he was chair of the board. In this period, however, he was no longer a starry-eyed idealist. The initial stages of establishment and development were long in the past, and he now prioritized security, consolidation and the further professionalization of the institute.

Rinde died on 28 May 1994, survived by his wife and two children.

Rinde’s attitude to research-related dilemmas

Conversation with Fredrik Engelstad, director of the Institute for Social Research 1986–2007

Fredrik Engelstad. Photo: Institute for Socal Research

LEA: When one conducts research in the social sciences, one often encounters points of intersection and dilemmas. What kind of research did Erik Rinde prefer? Qualitative or quantitative research, for example?

FE: Quantitative research was foreign to him. Non-quantitative research was the fashion in the 1950s, when he was most active as a researcher. At least from a contemporary perspective, his preferences lay clearly in qualitative research.

LEA: At PRIO, we say that we must be both relevant and scholarly. Citation counts are an expression of quality, which we see as the absolutely most important thing, but at the same time our research must be disseminated to users in order for us to fulfil our societal mission. In contrast, the most important thing for think-tanks is to be noticed, while the quality of what is said sometimes seems less of a priority. Can you tell us a little about how Rinde as a facilitator for social science research positioned himself at the intersection between quality and relevance? Should ISF function as a think-tank, or should it be more like a university, where scholarly results are the prime concern?

FE: Scholarly considerations were not of overriding importance. I would say that there was, and still is, an ambition to unite scholarly and societal relevance. Initially, researchers at the institute felt they were seeking new methods for building a society. In other words, relevance was the key consideration: now they were going to crack the code for how society functions, in order to build it well.

The Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning [The Norwegian Journal of Social Research] was founded in 1960. If you look at the early years, there was a lot of applied research there. There was also some philosophy, but tending very much in an applied direction.

See also an article about ISF published in the Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet on 26 October 1963, written by Eva Lie, who later joined the institute’s administrative staff following her journalistic career. Titled Til menneskets indre – i klosterinspirert hus [To humanity’s interior – in a monastically-inspired building], it was reproduced on pages 51–57 of the institute’s 50th-anniversary Festschrift.

LEA: How did this orientation towards applied research fit with the goal of obtaining funding from the Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities (NAVF)? If we look at how the Research Council of Norway operates today, it typically funds scholarly research, while government ministries tend to be more oriented towards applied projects.

FE: Well, it’s not really that simple. It’s certainly correct that in ISF’s first decades, the Research Council of Norway – at that time the NAVF – was a key source of funding. But the Research Council funded and continues to fund very many applied-research programmes. The majority of the programmes are funded by government ministries, which accordingly also define the research questions (but not, of course, the findings and solutions). Finding a balance between scholarly and societal ambitions is, and has always been, one of the most important challenges for the leadership of the institute. There is always a danger that there will be too little time for in-depth research, when the demand to stay relevant is there all the time.

LEA: PRIO has at times, at least until Sverre Lodgaard’s reforms in the 1980s, been described as a “nest of radicals”, who leaned far to the left politically. Was Erik Rinde a Left-wing radical?

FE: Ha ha! No, absolutely not!

LEA: Another dilemma that research environments may encounter is the need to maintain favour with the authorities who are funding the research, while at the same time one may need to be critical of them. How did Rinde and ISF deal with this ever-present tension?

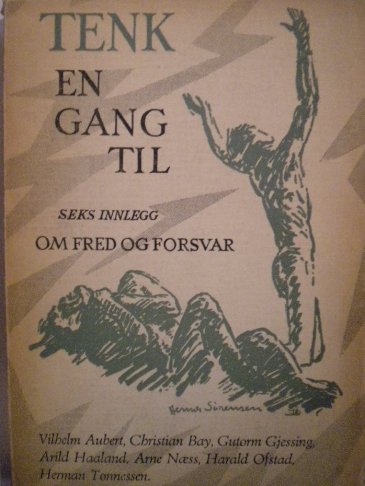

FE: They were in favour of being critical, that was completely clear. You can see this clearly reflected in the book Tenk en gang til [Think one more time] about peace and defence. The book emerged from the research environment around ISF and was published in 1952.

FE: They were in favour of being critical, that was completely clear. You can see this clearly reflected in the book Tenk en gang til [Think one more time] about peace and defence. The book emerged from the research environment around ISF and was published in 1952.

LEA: Okay, until 1972 ISF got funding from Sigurd Rinde, so then perhaps they could allow themselves to criticize the government. Did things change when the institute became dependent on annual basic state funding? Did one have to become more cautious?

FE: No, I never experienced any kind of bowing and scraping to the government, not at all. And most of our research was Research Council-funded; very little was directly funded by individual ministries. And on the Research Council sat people who were friends of the people running the institute. So the funding circulatory was a bit different at that time.

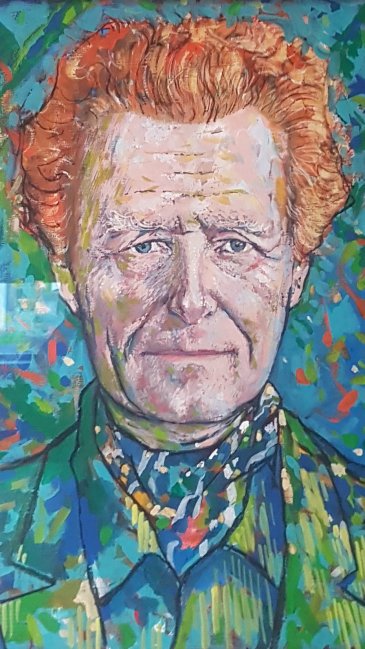

LEA: When were the portraits of Erik Rinde and Vilhelm Aubert hung in the room over there?

FE: They were painted after Rinde’s death. It was Hans Normann Dahl (1937-2019) who painted both pictures. They’re very good, particularly the one of Vilhelm Aubert. Dahl

Vilhelm Aubert (1922-1988). Detail of painting by Hans Normann Dahl. Photo: Lars Even Andersen

was a very good caricaturist. He was also a close friend of Aubert. In general, Aubert exuded great authority, he was completely reliable, everyone trusted him. He was also a kind of grandfather figure in political environments, while Erik Rinde was a little more distanced from people outside our innermost circle. So Dahl didn’t have any kind of personal relationship with Rinde, and painted the portrait from photographs. The portraits turned out to be very good likenesses – Aubert with flaming red hair, and then Rinde looking slightly more reserved.

Peace research

The Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) would also benefit from Rinde’s entrepreneurial skills and financial muscle. In many ways, it may seem paradoxical that the profits the family made from war enabled the founding of a peace research institute. Perhaps Rinde was eager to make some repayment, to the right environments?

Johan Galtung was born in 1930, and accordingly was slightly younger than the other academics associated with ISF. In the early 1950s he served a six-month prison sentence for refusing to do his military service, because he objected to completing the part of his civilian national service that would have made it longer than ordinary military service. Galtung used his time in prison to work on his master’s degree, and joined ISF after his release.

In 1955, Galtung published his book Gandhi’s Political Ethics in collaboration with Arne Næss. This was a study of the ethics of nonviolent conflict resolution, where the dominant perspective was philosophical, but where one of the intentions was to facilitate cross-disciplinary collaboration by deducing hypotheses that social scientists could subject to empirical testing.

We put 1957 as the year when Rinde and Næss began to develop plans for a research programme in the field of “nonviolent conflict resolution”. Internationally the concept of peace research had existed ever since the war, and Columbia University was particularly active in the field. Galtung had taught on a course on conflict research at Columbia in the academic year 1957–58, and drew inspiration to advance this field of research from Professors Otto Klineberg (1899–1992) and Paul F. Lazarsfeld.

In 1958, ISF arranged a Seminar on Conflict Research in collaboration with the Philosophical Institute, where Næss was based. Rinde and Næss hoped this initiative would reveal a social-sciences perspective on opportunities for empirical and comparative research into the hypotheses encompassed explicitly and implicitly by Gandhi’s doctrine of nonviolence. Contributors to this seminar included American guest researchers at ISF such as Daniel Katz, Alvin Zander and Irving Janis, as well as Gene Sharp and, of course, Johan Galtung. The seminar led, among other things, to the publication of an article titled “Toward an international program of research on the handling of conflicts” in the Journal of Conflict Resolution (3) 1959, in which the authors, Rinde and Rokkan, described their visions for the programme.

At Christmas 1958, Rinde gave the green light for the establishment of a Department for Conflict and Peace Research at ISF. The department was established formally at a board meeting on 29 May 1959, but in practice the department had already been up and running since the start of the year, under Galtung’s leadership. Other members of Galtung’s original team included his wife Ingrid Eide (born 1933) and Mari Holmboe Ruge (born 1934).

Rinde was enthusiastic and provided invaluable financial assistance. Initially, he provided operational funding for a three-year period. Later there were occasions when half of the Rinde family’s annual funding to ISF was earmarked for its conflict and peace research.

Once the initial three-year period of “guaranteed” funding expired, it became necessary for the peace researchers to look for other sources of income, both for their research projects and for core operations and strategic development. Work on obtaining such funding culminated in Rinde and some researchers meeting with prime minister Einar Gerhardsen, foreign minister Halvard Lange, and education minister Helge Sivertsen on 18 January 1962 in order to seek state funding for a “fund for scholarly research targeted at constructive work towards peace”. This meeting resulted in the establishment of the Council for Conflict and Peace Research (RKF) which, despite the fact that the council’s funds were not earmarked for specific institutions, in practice secured a steady stream of funding for Galtung’s department from the national budget. The first tranche of RKF funding arrived in the 1964 financial year and comprised NOK 120,000. The ability of the research milieu to attract political support at such a high level bears witness to good preparation, contacts, and strategic skills.

In January 1964, the department moved to separate premises at No. 8 Gydas vei, on the other side of Oslo’s Majorstua neighbourhood. The department was growing quickly and there was not enough space in the ISF building.

As time went on, there became talk about the peace researchers separating from ISF to form their own legal entity. This was a natural consequence of the department’s growing maturity and the fact that it now had its own income stream. There was also recognition that from a strategic perspective it was natural, not to say necessary, for it to be separated officially.

Rinde was still very positive about the department, but recognized that ultimately it had become ready to leave the nest. Rinde even sent a letter, co-signed with Galtung and others, to the RKF in the spring of 1965, in which he argued that the peace researchers’ annual funding should be made permanent, and that this increased degree of predictability would allow the department to become an autonomous institute. As mentioned above, the research environment had good political contacts, and accordingly a justifiable hope that the proposal would be taken up. However, a change of government in the autumn of 1965 meant that it came to nothing at the time.

The ‘divorce’ took place nevertheless, with effect from 1 January 1966. Naturally Johan Galtung took on the role of director, while Rinde became chair of the board.

At the same time, the new institute would not be economically independent for some time yet. Funds from Rinde were essential to accomplish the move that same year to No. 2 Frognerseterveien – a wooden chalet that has long since been demolished to make way for the South Korean ambassador’s residence. But there seems to have been an element of homesickness, because in 1970, PRIO moved back to the same neighbourhood, taking up residence at No. 28 Tidemands gate. At the time, Galtung had just left PRIO to take up the newly created Professorship of Peace Research at the University of Oslo. PRIO bought the building relatively cheaply from the Onsager shipping family.

“Katanga” (Fuglehauggaten 6). The building was torn down in 1978. Photo: Institute for Social Research

Originally there had been an old, yellow Swiss-style chalet on the ISF plot, with the main entrance from Fuglehauggata. Aubert and the sociologists had their offices in this villa. It was nicknamed Katanga after the province that attempted to break away from Congo in 1960. The chalet was demolished in 1978 to make way for the second phase of the ISF building. Rinde and ISF also had at their disposal a brick villa right next door, at No. 29 Munthes gate, which was home to the Psychoanalytic Institute. During this period, the researchers at ISF, the Institute for Applied Sociological Research (INAS), Katanga, the Pyschoanalytical Institute and the peace researchers no doubt saw themselves in many ways as a collective. The founding objectives of the different institutes were to a large extent similar, and all the researchers remained part of an inner circle in neighbouring premises. Rinde negotiated leases and purchases of the premises as time went on, and it became a kind of idyllic research community.

Accordingly, the fact that Erik Rinde for a long time sat on the board of ISF while also serving as chair of the board at PRIO did not constitute a problem. There were never any conflicts of interest. On the contrary, there were many collaborative projects, and Rinde was important in promoting connections that helped facilitate and harvest from their synergies.

At the same time, it is important to stress a significant distinction between the institutes in this period. While ISF ever since its foundation had had the specific goal of building up the university sector and acting as a provider of professors in the social sciences, PRIO had never explicitly had a similar objective. Like ISF, PRIO belongs to the sector of autonomous research institutes, and it has never been tempting for it to become part of the university system. The peace researchers wanted to go out into the world and build up a base of knowledge about peace, and from that point of view Norway was less important as a catchment area. This almost activist orientation was quite foreign to Erik Rinde, who was interested primarily in theoretical research. In addition, there was the paradox that the research environment had emerged from the collaboration with Columbia, but as time went on had become fairly critical of the United States, including the latter’s involvement in the nuclear arms race and the Vietnam War. Galtung first found himself at the point of intersection when he was working with established theories and models, but gradually moved in a more radical direction, a development that Rinde did not view with any great enthusiasm (2).

This is because Erik Rinde was a straight-laced man who prioritized keeping in with the Establishment. Unlike the young scientists, and particularly the peace researchers who never wore ties, Rinde was always impeccably dressed; it would have been unthinkable for him to wear jeans. This was no doubt useful for meetings with the Research Council, government ministries and so on, as it served to counteract PRIO’s periodic reputation as a nest of radicals.

We do not know whether Rinde ever made public his political views. Like many others at PRIO, he may have sympathized with the Socialist People’s Party (SF – a splinter of the Labour Party that existed from 1959 to 1973). But his business-like demeanour meant that he was generally believed to support the Conservatives. And at ISF he imposed a clear rule that no one should be affiliated with the Marxist-Leninist Workers’ Communist Party (AKP m-l), which he viewed as a threat to democracy (3). But in the great scheme of things, Rinde was not particularly interested in party politics.

At the same time, Rinde understood and supported PRIO’s commitment to ‘engagement’ quite simply because he was very concerned about peace.

At the same time, Rinde understood and supported PRIO’s commitment to ‘engagement’ quite simply because he was very concerned about peace.

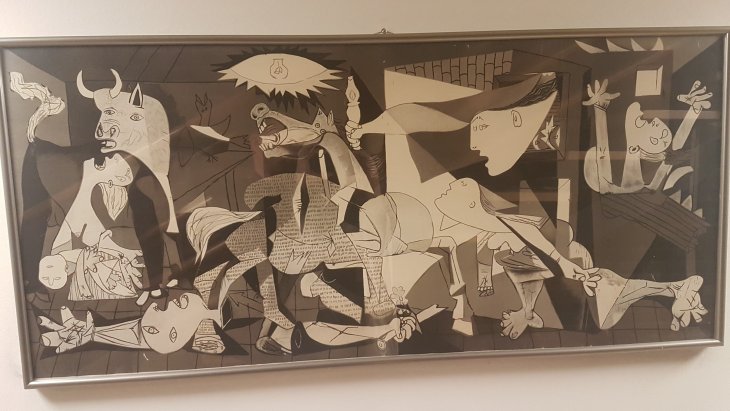

A print of Picasso’s Guernica hangs on the staircase by the Institute for Social Research’s library. The image had an essential position in PRIO’s activities, and thus it is a ‘sacred’ image for ISF. PRIO also has a copy on the wall in its ‘War Room’. Photo: Lars Even Andersen

Rinde was chair of PRIO’s board for 13 consecutive years after the ‘divorce’ from ISF. This is a record at PRIO, although Bernt Aardal came somewhat close to it in the years 2007–16.

Rinde resigned as chair of PRIO’s board in 1979, when he got cold feet from the prospects of legal prosecution against Nils Petter Gleditsch and Owen Wilkes. This did not cause any particular problem, as Torstein Eckhoff, a professor of jurisprudence who had been a board member since the start, was willing to take over. Accordingly, Rinde and PRIO parted as friends.

Financial stratagems under Erik Rinde’s chairpersonship

Related by Nils Petter Gleditsch

After just a few years of department-based financial support from the Rinde family, PRIO secured annual funding from 1964 onwards from the Council for Conflict and Peace Research (RKF). While this eliminated the need for ongoing operational funding, Rinde remained positively disposed and continued to make contributions over the following years when circumstances suggested it.

One such occasion arose in 1970 when PRIO wanted to move back to its old neighbourhood after six years in exile, and decided to buy office premises at No. 28 Tidemands gate for NOK 600,000. Since PRIO had no capital of its own, and needed a little extra money to fit out the offices and buy office equipment, the purchase was funded with a loan of NOK 540,000 from Fellesbanken and a private loan of NOK 100,000 from the Rinde family. In other words, the building was mortgaged beyond the hilt.

When Sigurd died in 1972, however, funding from the Rinde family dried up for good. In addition, there was an acute financial crisis when the other members of the family wanted repayment of the NOK 100,000 loan. Nils Petter Gleditsch was director of PRIO at that time, and he resolved the situation as follows:

NPG: First Erik Rinde got us an extension (of six months, I think) for paying the money back. Then four of us took out personal loans of NOK 25,000 each to repay the loan. Then we opened an account at Fellesbanken and paid into it all the available cash. Next, we didn’t pay any bills until just before debt collection proceedings began, so that we would build up a good customer relationship with the bank. Remember that at that time ‘customer relationship’ was the magic concept when it came to getting a loan. Then I had a friendly chat at the bank with Bjørn Piro, the company secretary and the younger brother of my old classmate at elementary school (who was also my neighbour) Christian Piro, and so we got the necessary additional loan approved by Fellesbanken. And so we got through the crisis.

The building at No. 28 Tidemands gate was actually classified as residential, and when PRIO bought the building, there had been an assumption that an application to reclassify the building for office use would go through. It didn’t. After a while, all the formal and informal dispensations had expired, and PRIO was really on borrowed time when it relocated again in 1976, this time to No. 4 Rådhusgata.

PRIO also made good use of the reimbursement arrangements for VAT (value-added tax):

NPG: At the suggestion of Inge Samdal (who originally did his civilian national service at PRIO and went on to become a research assistant in the 1970s), we registered ourselves for VAT. Since our VAT-liable income was limited (sales of publications), but we bought many VAT-deductible goods that were used to produce these publications (paper, office equipment etc.), we got a VAT refund that far exceeded the VAT we had to pay on our income. Given how hard up we were at this time, not least due to the purchase of the building in Tidemands gate, this money was very useful.

Erik Rinde, who was still chair of PRIO’s board, was very concerned about financial propriety, and no doubt he was not particularly enthusiastic about these stratagems, even though he let them pass.

NPG: Rinde was concerned on several occasions about our financial and organizational manoeuvres. He thought, no doubt with some justification, that we were bending the rules. Even so, we got it approved by our auditor, who was also the auditor for ISF, so there wasn’t much he could do about it.

Alas, in 1979, when it was apparent that Gleditsch and Wilkes were going to face legal charges for breaching the national security provisions of the Penal Code with their ‘rabbit report’ (4), Rinde had had enough and resigned as the chair of PRIO’s board.

More than 50 years after the ‘divorce’, PRIO’s historically close links to the Institute for Social Research are still reflected in PRIO’s constitution, which provides that in the event of PRIO’s dissolution, any residual assets would go to ISF.

Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext