Henrik Syse, interviewed by Trond Bakkevig

Photo: Julie Lunde Lillesæter / PRIO

My Christian faith was formed in an intellectual framework. I do not mean intellectual in the academic sense of the word. It was more that thought became part of my faith.

This is what PRIO’s first philosopher, Henrik Syse, tells PRIO’s first pastor, Trond Bakkevig, in the beginning of the dialogue that follows – about faith, justice, reconciliation and PRIO as a home for peaceful thinking.

Trond Bakkevig: Henrik, when were you born?

Henrik Syse: I was born April 19, 1966, just when the Beatles recorded Revolver and at a time when my father (Jan P. Syse, Member of Parliament 1973–97 and Prime Minister of Norway 1989–90) still had not entered politics full time. My parents had just moved to Uranienborg, which is in the western part of the inner city of Oslo. I grew up there, with my elder brother Christian, and my parents Else and Jan.

And you went to Uranienborg elementary school?

The six years at Kristelig gymnasium meant a lot to Henrik Syse. Photo: Jan-Tore Egge – Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Yes, grades 1 to 6, 1972–1978. Then to KG, Kristelig Gymnasium, for six years, through high school. KG was a school with a strong Christian basis. Some might think it was somewhat narrow, and on top of that, it also recruited many students from the wealthier parts of Oslo. But it was more pluralistic than many probably thought and recruited students from all over the city. I had a good time there. Those years had a definite influence on what I have since been doing as a researcher and professor. It was a place where intellectual curiosity was nurtured. My teachers were genuinely interested in what I thought and meant, and discussions about important, existential questions were part of daily life – a place where we also lived well with disagreement.

Faith and Early Thoughts

Is that also where you became rooted in your very clear Christian faith?

Yes, but then again, the words ‘very clear’ need to be nuanced: not because my faith is not real, but because what I arrived at was in many ways an intellectual framework. I do not mean intellectual in the academic sense of the word. It was more that thought became part of my faith. I came from a home where we did not often go to church. My mother came from a family where they often did, whereas my father’s family were members of the church, consciously – they were baptized and confirmed, and they had deep respect for the church – but it was not part of everyday life. So, Christian culture and faith was a kind of mother tongue around me, with for example evening prayers before I went to sleep, but at the same time not something I encountered institutionally all the time. That was my background.

At KG, I felt I had to relate more consciously to this background. In a way, KG forced this upon me, with such things as the school’s daily prayers: is this just superstition? Is it a kind of fairy tale? Is it indoctrination? Or is it a message that I have to respond to, which expresses a historical and metaphysical truth, or at least a guide to truth? It was at that point I became aware that in this message there is much of what is most important to the lives we actually live.

Some of the teachers were quite conservative, both theologically and politically. They especially did not like the Labour Party, since it had for a long time been against independent schools like KG. My father thought it was a bit embarrassing when, at a parent-teacher meeting, they seemed to pray to God in thanks that the conservatives were voted into power. He was a conservative, who later became a prime minister, but I know he did not feel well during that prayer. In spite of this, there was room for different opinions at KG, both theologically and politically. And I learned many hymns and songs. We sang a lot. I am so happy to have that as part of my mental baggage.

We should sing more!

Yes, indeed! We had a small Christian songbook that we used every day. Some of the texts were somewhat naïve. But there is much that is valuable about them. I often hum hymns and songs to myself, which I learned back then.

Discovering Philosophy

Am I right in thinking that this was when you decided to study philosophy – against the background of this meeting between thought and faith?

In many ways, yes. My brother read some philosophy for a university exam, I remember. I was 17, and with my background from high school, I looked at his books and thought: there must be something about St. Paul in these books. I had read his letter to the Romans at school, discussed it, and thought that this was philosophy. Think of what he says about the relationship between what you know you ought not to do, and what you actually do. But then I discovered that in the books on philosophy there was very little about the Bible or about explicitly religious topics. Yes, there was a chapter about St. Augustine and the medieval thinkers. I learned more about this later. My first impression, however, was of a philosophy almost without religion.

And the textbooks by professor Arne Næss did not have much about religion?

That’s what I realized, too. There was really not much serious reflection about religion, or so at least it seemed to me. And it puzzled me. I thought there must be something here I need to find out more about. What is this relationship between philosophy and faith, between reason and religion? All of this became an important motivation for me to work on what we can broadly call philosophical questions. It did not mean that I had decided to become an academic philosopher, that was more coincidental. I had finished the introductory exam in philosophy, which was obligatory for everyone who would study at the university (Examen Philosophicum), but I had to wait more than a year before I could start my studies in the Russian language in the army, which I was planning to apply to.

Henrik Syse appointing the comedian Harald Heide-Steen Jr as honorary Russian for his famous act as submarine captain. Photo: Private

One of my teachers at the University of Oslo, Arne Tuv, suggested that I use the time in between to study more philosophy: ‘Now that you have worked so diligently for your preparatory exams in philosophy, you’re already halfway there!’ I thought that was a brilliant idea, and I remember that first semester of philosophy – grunnfag, as they called the first year – as one of the finest experiences I have ever had. I could dig deeper, I tried to understand Hume’s empiricism, and worked a lot on St. Augustine’s Confessions. I saw that they opened up issues I thought were truly important – well, they are important, period – and I recognized that these were indeed all those questions we had discussed so intensely during the years at KG, and which helped me also explore the relationship between faith and reason. So, I studied philosophy up to the mellomfag (major) undergraduate level before I joined the army and studied Russian there, and later at the University from 1986 to 1988. Then I added English as my final subject, finishing my Bachelor’s degree right before my father became prime minister in 1989, and I had to leave my position as chair of the Oslo chapter of the young conservatives (Oslo Unge Høyre) because Hanna and I were going to study in the US. That was in August 1989.

Hanna and I had actually got married that summer, and we went on what we later have called our two-year honeymoon. We left for the US – she to study English, and I to study philosophy and politics. We could have been at Columbia University in New York, where we were admitted, but decided on another university, Boston College, because of the programmes and courses they had, which fit us really well. I followed a programme in political science, with emphasis on political theory. In reality, I more or less finished a Master’s programme in philosophy, even though it was in the Department of Political Science. Boston College was a Jesuit university, but the political science department was heavily influenced by the students of the secular Jewish philosopher Leo Strauss (1899–1973). This opened for many interesting discussions.

Henrik Syse at Boston College. Photo: Private archives

I learned a lot from the close reading of texts, which was very much emphasized there. I got to know Plato and Aristotle, but I admit that I regret to this day that I did not take the time to learn classical Greek. I learned some of it when I returned to Oslo, and have worked quite a lot in the philosophical terminology, but I have mostly had to rely on translations. Anyway, it was a wonderful time where I really got to wrestle with important texts, and not least with the relationship between politics, philosophy and religion – those topics that had followed me since KG.

Back in Oslo, I was admitted into an interdisciplinary doctoral programme on ethics under the umbrella of the Research Council of Norway. It must have been one of the most valuable programmes ever in Norwegian higher education, with interdisciplinary courses combined with a solid foundation in moral philosophy, chaired by the wonderful philosophy professor Dagfinn Føllesdal, on whom I am just now co-writing an academic article for a Norwegian philosophy journal, centring on exactly the Ethics programme.

I finished my doctoral thesis in 1997. My good friend Tom Eide, who was the leader of the secretariat of the programme, was in touch with Dan Smith, who at that time was Director at PRIO. Dan had told him that they had started a new project on international ethics and the ethics of war at PRIO. At this time, only Dan and Mona Fixdal, who is still doing valuable research in this field, were involved. They had some funds from the Ministry of Defence and needed a senior researcher. ‘For one year’, Dan said, ‘then we will see’. At that time, I still had not even defended my thesis. And that’s how I came to PRIO.

Theology and Philosophy

Let us pause for a moment: what was your thesis about?

It was about the idea of natural law, that is, the idea that morality and politics have their basis not merely in human will, but in laws and patterns that are natural or at least independent of mere human volition. This was a topic I had started working on in the US. I had several teachers who were deeply fascinated by the question of whether morality, or ethics, has a foundation outside of human agreements and contracts. The most important one was probably Ernest Fortin, who was a theologian, an Augustinian monk, actually. His research and teachings were situated at the crossroads of theology, philosophy and political science. He taught much political theory and was inspired not least by a book by Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History (Chicago, 1953). He had known Strauss quite well.

Do we need to return to the classics, the ‘ancients’? Did they have an insight into right and wrong that we have lost, and are we within modernity developing a kind of deep-seated relativism, which in turn gives us no power to resist the authoritarian and the totalitarian? Or is it the other way around?

Strauss’s main thesis is that in the West and in modern liberalism, there is a break within the tradition of natural law, with far-reaching consequences for all of western politics and philosophy. In the original natural law tradition from Plato and Aristotle, they struggled to find the preconditions for knowing what is right and what is wrong. Theologically, this was continued within Christianity, especially with Thomas Aquinas, who ultimately thought of natural law as a law coming from God. Then came Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and other thinkers in early liberalism, who inverted this and turned natural law into a concept of natural rights that humans possess as individuals. Even though it is presented by them as a kind of continuation, the modern, liberal version of the classical thinking around natural law – which developed into such milestones as the US Declaration of Independence, modern democracy and the UN Declaration of Human Rights – in reality represents a radical break, according to Strauss and Fortin.

The question today is how we deal with this break, and even whether it actually is a break. Has it been a resounding success, which is how a Steven Pinker would talk about the Enlightenment and modern, natural science? Or, has it led to totalitarian catastrophes, and moral and political crises? Do we need to return to the classics, the ‘ancients’? Did they have an insight into right and wrong that we have lost, and are we within modernity developing a kind of deep-seated relativism, which in turn gives us no power to resist the authoritarian and the totalitarian? Or is it the other way around: does this modern version of natural law protect humanity and freedom, while the older forms of thinking were superstitious and authoritarian?

To Strauss, the fallacy of believing in the modern model became evident in light of Nazism. Before the Second World War, he had corresponded and interacted with the famous lawyer Carl Schmitt, who became a supporter of the Nazi party. If you do as Hobbes and Locke did, and separate natural rights from a larger body of law, making them the property of the individual, you enter the road towards total relativism, said Strauss. The result is a Hitler or a Stalin, who promises to fulfil all human wishes and needs. The point of someone like Leo Strauss is that we have lost the philosophical protection against this. This was the ‘rallying cry’ of students of Strauss, and it remains so to this day: ‘return to the ancients’. This way of understanding the history of ideas was different from what I had learned at the University of Oslo. I had not really dealt with these questions in this kind of way.

But, the weakness in Strauss’ thinking is that it essentially sees the classics, Plato and Aristotle, as representing a kind of thinking where we gain insight into right and wrong through philosophical rationality alone. And the underlying danger, hinted at by Strauss, is that philosophers might find out that it is not possible to find out what is right and wrong after all, but they have to hide this dangerous insight from the people.

The more optimistic version of the ‘return to the ancients’ argument says that philosophers, through dialogue, through philosophy, and through nurturing virtues, can tell society how to organize and how life can be lived – that classical philosophy is the way to gain insight into what is righteous and good. Hence, we must return to their wisdom and leave behind the relativism of modernity. Many students of Strauss, however, see this as only his surface teaching – that he was actually more pessimistic, and that we therefore have to leave it to philosophers to rule society, since they are the ones who can protect us from dangerous truths.

Strauss and his students have had much influence, especially in the US, emphasizing the point of view that philosophy is basically the rational study of the world, whether that rationality succeeds or not. The consequence is that there is a fundamental contradiction not only between ancients and moderns, but also between philosophy on the one side, and faith and revelation on the other. According to this way of thinking, to open oneself to religious revelation is the same as submitting to a divine truth, which is superior to human truth and rationality. That, according to Strauss, leaves no room for real philosophy. Strauss held that the big, truly formative intellectual and spiritual struggle in the history of Europe is the one between Athens and Jerusalem. He says that you cannot be both a philosopher and a theologian – you have to make a choice. That tension constitutes the lifeblood and core of European thought.

I thought: ‘This is not satisfying’. It was like the first time I saw books on philosophy. Should we not instead take seriously the human experience of being part of a larger reality, indeed, that life itself is a revelation? Thomas Aquinas called it ‘natural revelation’. We cannot just put all of that – faith, spirituality, the belief that there is a God – aside and say it is something totally different from philosophy, especially if philosophy ends up being some secret teaching of elite philosophers who must hide the real truth from the people.

A fellow student of mine at Boston College recommended that I read one of Strauss’ contemporaries, also a German immigrant, Eric Voegelin (1901–1985). He managed to flee Nazism and taught at Louisiana State University in the US. In the fifties and sixties, he also taught in Munich with my former, lovely office fellow at PRIO, Helga Hernes, as one of his students. Voegelin’s last years were spent at Stanford University. Voegelin had an important correspondence with Strauss, recorded in one of the finest books I know: Faith and Political Philosophy (1993). Voegelin said that we as humans find ourselves in a tension between the changeable and the unchangeable. He uses a platonic concept, metaxy, which means to be in the middle, in-between. To be a human is to live in the metaxic situation, in the tension between what is greater than we can grasp on the one hand, and concrete, physical reality on the other. In that tension between what we can sense of the eternal, of unchangeable principles, and the experience of living in a world where everything changes, is where we find ourselves as human beings, at all times.

I saw this way of reading the history of philosophy as having great depth: it’s not a history about humans thinking different things which are then laid on top of each other, it’s a history of humans meeting reality through experience at all times, and that includes the experience of the transcendent and the divine. If we look at the paintings in ancient caves and ask what experience is mirrored here, we will see that it is all about this meeting between myth and reality. The myths are, in other words, not the same as fairy tales: they are a search for truth.

After these philosophical encounters – after having read Strauss, Voegelin and Plato’s dialogues, and having read about natural law – I understood how complex, but also how important, the issue of natural law is: can we as humans gain insight into what is right and wrong in a world where so much is contingent and changeable? Can we have insight into what is changeable – or what is eternal? Do the ancients and for that matter the medievals view this completely differently from how we do in modernity? Is there a ‘break’, and if so, what does that consist in? I originally wished to write a dissertation on medieval philosophy, but if so, I would have had to spend years learning Latin. I did not have time for that with the kind of scholarship I had, so I decided to write about Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and use their English-language texts. I used what I had learned about Greece and the Middle Ages to mirror that and to deepen my understanding of what their natural law philosophy actually says.

I wrote a dissertation I am fairly proud of, although it could obviously have been better. It did come out as a book some years later (Natural Law, Religion, and Rights, South Bend, 2007). Maybe it wasn’t directly relevant for my later work at PRIO, but at the same time, many of these thinkers had formulated crucial ideas about wars, asking whether they could be just and in conformity with natural law. And that became an important part of my work at PRIO. Many of those who come from the natural law tradition indeed contributed to formulating what we today call just war theory: Plato, Cicero, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, Hugo Grotius, John Locke …

And what Dan Smith and Mona Fixdal really wanted to find out is whether this language and framework could be used to analyze current conflicts. So this is how I came to PRIO, and how my philosophizing on natural law and right and wrong finally came to practical use.

Yes, there is a continuity here, the relationship to international law, Hugo Grotius and …

Yes, and this is indeed what I have been working on at PRIO. Dan Smith could tell you more about this. His thesis was that the Balkan wars – this was in 1997 – was a crisis in Europe, a moral crisis. After the end of the Cold War, we did not handle the underlying tensions in the Balkans in a way that saved human lives, within a moral and legal framework, a framework which could also tell us whether there are circumstances where it is right and justified to use armed force, and, if so, what are right and wrong actions in war. Dan’s thesis was that this is a moral issue – it’s not only a question of politics and international law.

When politicians and political scientists do not know the language of ethics, there is an imminent danger. They may know international law and even the Geneva Conventions, but issues like the ius ad bellum, whether it can be right to use force, require a genuine moral debate – and the reasoning behind all the conventions need to be examined. Dan thought PRIO should engage in these kinds of issues, maybe even find an academic niche. He said, in short, that the discussions about a possible armed intervention in the Balkans were in reality of a moral nature, but politicians did not use this kind of language – or if they did, they did it very badly.

When politicians and political scientists do not know the language of ethics, there is an imminent danger. They may know international law and even the Geneva Conventions, but issues like the ius ad bellum, whether it can be right to use force, require a genuine moral debate…

The core idea of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, and more broadly the tradition of natural law, is that there are some common standards that need to be understood and obeyed in order to protect human dignity. If holocausts, world wars and the nuclear bomb are not to ravage the world again, we must agree on certain norms. Hence, there is a close relationship between the tradition of natural law, across the centuries, and international law. Hugo Grotius expresses this most clearly, right at the dividing line between the classic and the modern, between Thomas Aquinas and Thomas Hobbes, so to speak. And he formulated many of the standards of international law that we build on today.

Early years at PRIO. Henrik Syse around 2000. Photo: PRIO

I really enjoyed working on this. There is indeed a continuity for me from KG to PRIO. But, if anyone had asked me in December 1996 if I was going to be at PRIO and work on these issues, I would have doubted it very much. But, when the telephone rang that second week of January 1997, I thought, ‘yes, absolutely, wonderful’. Then again, I never thought I would stay here so long.

A Philosopher among Social Scientists

And, how was it, as a philosopher, to enter an institution so much shaped by the social sciences?

From the first minute I felt that PRIO, much thanks to Dan Smith and Hilde Henriksen Waage and several others, is a place where people are curious and open-minded, and that they were grateful for taking part in philosophical discussions. Afterwards, I got to know that there had been some internal discussions about inviting me in. I still had not defended my thesis, but Nils Petter Gleditsch had read one of the chapters, on Thomas Aquinas, and concluded that, yes, we want to have this kind of thinking at PRIO.

To me, one of the best things at PRIO is that we have these professional tensions. My colleague in the field of philosophy, Greg Reichberg, and I say to each other that we understand fully less than half the articles in the Journal of Peace Research. We do not understand what this or that graph is meant to illustrate or what its formula means. We can read graphs, but do not understand the method or the significance. This is probably also an issue about the relationship between quantitative and qualitative approaches. Nils Petter Gleditsch will insist that the quantitative comes before the qualitative, at least chronologically, since you cannot have a discussion about qualitative issues before you know what you are discussing. Some of us will, however, say that for fundamental philosophical and terminological reasons, the qualitative work must come first. But, I have always felt that at PRIO, there is an openness and curiosity around these issues, and I have always felt pride in being at an institute encompassing both positions and fostering debate between them.

Non-Pacifist Peace Research

Then, the question I am quite sure you have anticipated: there were not many members of the Conservative Party (Høyre) in the staff of PRIO at that time?

Probably true! As for myself, I was active in the youth chapter of the party, and chaired the Oslo organization (Oslo Unge Høyre) from 1988–1989. When we returned from the US, I became a member of a local, municipal governing body, and served on some committees here and there. I was a proud son of my father, and represented what I guess I would call moderate, internationally oriented conservative points of view. But I was not an active politician by any means.

Anyway, was this somewhat contrary to dominant political points of view at PRIO? Well, coming to PRIO for the first time, the first person I met was a friend from the student and youth organizations of the Conservative Party (Else Marie Brodshaug)! She was finishing her Master’s degree with Nils Petter as her supervisor. I thought, ‘If she’s here, I can be here, too’. Professor Bernt Hagtvet, a member of the PRIO board back then, said that when a Syse comes to PRIO, then peace has come to Norway. Funny! But I very soon discovered that people at PRIO were not only curious about politics, but also about philosophy, and that there was a wide variety of political views. And there were wonderful people there. I could mention so many, so just mentioning a few feels wrong. But I just must include my many conversations with Hilde (Henriksen Waage) and the language lessons with our beautiful language teacher-in-residence, Karenanne (Bugge), who was already then well above 70 – well, those are stellar memories of human warmth and friendship.

Henrik Syse as student in the US, with his visiting parents. His father resigned as Prime Minister a few weeks before this picture was taken. Photo: Private / Hanna Syse

I also discovered that it was possible to work on the ethics of war and international law from a non-pacifist point of view. Greg Reichberg, who has become a fantastic friend and colleague, came to PRIO for the same reasons I did. I had recommended him to Dan and PRIO after getting to know him through another good friend, Professor Torstein Tollefsen, who teaches medieval philosophy at the University of Oslo, and he came to PRIO in 1998. For some years after that, Greg and I ran a seminar on military ethics, which also came to include the Norwegian Military Academy at Linderud (Krigsskolen). Retired generals participated, together with active-duty officers from the Army – and PRIO veterans. I remember it as a great time for truly wide-ranging and thorough discussions. PRIO was and remains a place for curiosity and thinking – also about issues that were not directly related to war, but which could have implications for peace and war, like trade. I have always felt not only that I was welcome at PRIO, but that I am part of it.

And in addition to your political orientation, you are married to a lecturer at the Military Academy?

Well, Hanna used to be there, from 1994 to 2006. Now she works in the Ministry of Defence. I always thought it was cool that she was at what we in Norway call the War School while I was at the Peace Institute.

And the point is that concern for peace can at the same time mean support for armed defence?

To me, it is necessary to combine support for armed defence and concern for the right and morally defensible use of force, with a deep concern for maintaining peace, and with the insistence that the use of force must have ethical legitimation. I believe that the Second World War and the threat from communism demonstrated the necessity of armed defence. At the same time, armed force can be misused terribly and lead to enormous suffering. But the need to defend oneself and one’s nation and the rule of law, even with arms, can live side by side with a strong commitment to peace.

For me, not least as a current member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, it is interesting to know that Alfred Nobel, who was not a philosopher but who was deeply engaged with questions of war and peace, earned his fortune on the production of explosives and bombs. He decided that part of his enormous fortune should be used for a prize to those who promoted disarmament and elimination of armies. He seems to have believed that arms were a precondition for peace. Until trust was built, one had to deter and be able to defend oneself. But the goal is disarmament. That’s a consistent position.

But pacifism always stands there as a moral challenge to those who are prepared to defend themselves with arms – just like doubt is a challenge to the believer. I believe that the basic values PRIO is built on are a constant challenge to guide our research towards preconditions for peace. Those basic values – to be international, to be interdisciplinary, and even more basically: to believe in the value of peace – will always guide what kind of research we delve into. Issues related to conflict and peace are literally issues of life and death. Our research can therefore never be totally neutral.

How would you then describe the relationship between this normative basis and the ideal that research should be free?

I believe that is a tension we have to live with – all the time. Norms guide us to the research questions we engage in. Even Max Weber and his so-called value-free science demonstrated that this was the case: what does the researcher decide to read, what does he or she assess as interesting, and what do we think are important questions? These issues are guided by values. We must be conscious about this, and openly express what our values are. Research should always be free, open, and not guided by personal or hidden interests, but we need to communicate and explain what kind of research we do, and why we do it. My normative points of view will always be there when I decide what to do, but our research should never for that reason be programmatic or opinionated.

Religion for and against War

Let us move on to your own research. Much of it has been concentrated on religion, politics and war. Can religion cause war?

Yes, it can. In 2014, Greg Reichberg, Nicole Hartwell and I published an anthology as part of a project supported by the Research Council of Norway. Together with some of the world’s leading experts, we looked at what the most important religious traditions say about the ethics of war. What do their texts actually say? How have their traditions developed? We wanted to get behind what popular opinion says about how different religions relate to violence and war. And the answer to your question is, I’m afraid, yes. I say, ‘I’m afraid’, since as someone who considers himself religious, I wish I could say: ‘It is not religion that creates war and conflict, it is human beings; they twist religion, and use it as ideology’. That may often be true, but there are many instances in history where we have to admit that religion has been at least a motivation for war.

I wish I could say: ‘It is not religion that creates war and conflict, it is human beings;’ […] All of us should ask: what is it in our religious tradition that has contributed to war? What is it in our tradition that is unethical? How should we deal with such texts in a serious way?

Yet we have to add two factors to this. The first is that we have to be careful not to declare monocausal reasons for what happens. In other words, religion does not need to be the single reason for war, or the decisive cause. It can be a supplementary factor, or it may have contributed to dynamics driving or intensifying conflict. Those same wars could have happened without religion. In the course of world history, it is often difficult to separate religion from politics. The other thing we must remember is that religion in many situations has also limited conflict or even hindered war. That has been the case not least when religion has relativized politics by reminding us that the most important questions are not those driving us towards war and conflict. There are more important issues in the world.

In addition to all of this, we know that religious thinking has contributed to international law. Much of the framework for our current Laws of Armed Conflict, including the Geneva Conventions, was provided by thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas and Hugo Grotius. This has definitely limited the destruction of war. So, there are two sides to this – as you, Trond, well know.

Yes, but you are the one being interviewed!

Yes, but you may have something to say against what I say.

Yes, maybe – my experience is that many current religious dialogues are attempts at convincing each other that ‘my’ religion really wants peace. Very few dialogues are about that which in ‘my’ holy book, or in ‘my’ texts, actually promotes violence and war.

I do agree. I made that as a rule of thumb in the summer of 2014 when we were in Jerusalem to present this anthology. There was unrest there then.

The Gaza war was about to start.

Precisely. When we landed in Tel Aviv, they talked about missiles that could reach the airport. Greg and I discussed how we could present our book in both East and West Jerusalem in this situation. This was the first time we had officially presented the book, and we expressed ourselves thus: if you find something in your own religious tradition, your own religious texts, your own religious books, which you are proud of and regard as furthering peace, then you can be sure that others have a parallel in their traditions or texts. There are many differences, but this is still true. And vice versa: if you react strongly against something in the texts or traditions of others, you can be quite sure that you will find the same or something similar in your own. Religions have throughout history played different roles. They have solidified power and they have challenged power, across religious divides.

All of us should ask: what is it in our religious tradition that has contributed to war? What is it in our tradition that is unethical? How should we deal with such texts in a serious way? The introduction to the anthology, which I wrote with Nicole Hartwell, is about this. But we also have to look at the context in which the texts were written. If not, such an exercise may only end in useless self-flagellation.

The Power of Texts

But what role do texts play in real life?

Prior to the last few centuries, most people could not read. Texts have been transmitted to them by others. Speeches given on occasions of war in the Middle Ages, speeches given to encourage and inspire warriors, used only adapted parts of texts. Speeches by European kings often had a limited relationship to Biblical texts. But what is important about texts, is that you may return to them and ask what was said at the time, and what do we see or know now, at our point in history. Could the same texts be used to resist current politicians’ use of them to legitimize wars? Critical and nuanced studies of texts are important in order to be able to correct and challenge contemporary opinions.

When I teach just war theory, I tell students that they may not end up knowing exactly what is right or wrong in questions of war and peace. Many moral questions are genuinely difficult. But, I tell them, ‘you need to be good at asking questions, good questions, so that when you meet a politician who says that this or that is unquestionably right in the light of our tradition, you can ask: “is it? Are you sure?” And if the politician says that this or that text says so, you may correct or nuance it, or ask critical questions’. Critical reading of texts is extremely important.

Norms and Presidents

Yes, but what is the relationship between those who read and those who have power?

Ahhh, an old and big question. Machiavelli understood himself as a counsellor since the king or the prince – or the president – never had time to read. The philosopher, the author, the interpreter of texts or the priest had to tell him what the texts say. This leaves considerable power to those who transmit what texts say. Hitler got a vulgar version of what Nietzsche said and many around him took that version very seriously. Carl Schmitt, a very knowledgeable jurist, used his legal insights to legitimize what the Nazis did.

But there are also those who can nuance, revise, and challenge current opinions. I was once told about an adviser in the White House who had written a doctoral thesis on just war issues. In the autumn of 1990, he was so frustrated that President George H. W. Bush seemed unable to convince people that they had a just cause in fighting Saddam Hussein after the invasion of Kuwait. The adviser then wrote a memo on ethics and just war, which was brought to President Bush. As a result of that, the President and his advisers immediately changed their language and used arguments and texts from the just war tradition – particularly in speaking to churches that were critical to the President’s policy against Iraq and Kuwait.

This is fascinating, not least because George H. W. Bush seemed to take ethical issues seriously. He knew that his position was problematic, many in Congress and among his political/the US allies were doubtful, and at the same time he understood that the moral foundation was important. He used texts and traditions, such as those derived from Thomas Aquinas. The first Gulf War was very controversial, by all means. But the discussion around it demonstrates that political discussions can be strengthened if academics participate – not uncritically, and not by serving power, but by contributing a terminology that improves discussions.

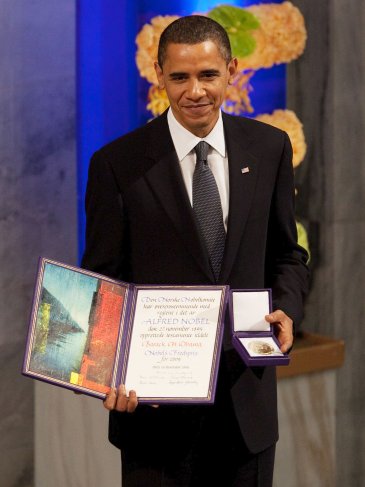

President Obama receives the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As when President Barack Obama gave his lecture after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize?

Yes. That was interesting. I was teaching the ethics of war at Bjørknes University College, and we had our exam at the exact same time as he came to Oslo. I told my students that if that speech had been written for our exam, he would have received an A. The speech was masterfully eloquent and quite nuanced. He wrote much of it himself – on the plane across the Atlantic. By that speech, I would say he legitimized the prize he got, after all the controversy around it. It was indeed a speech that defended the use of force, and he spoke as the United States Commander in Chief, so it remains controversial to this day. But he also spoke strongly about the moral limits to waging war. I am, overall, not quite sure that he later lived up to what he said, though.

Yes, this is often the problem with the relationship between ethics and politics.

It is. And about Obama, one may say of his politics that it is ‘intellectual realpolitik’, but with a strong moral foundation. He should probably have used more of his Nobel speech, his strong commitment to rights and international law, in his last years as president. Among other things, I am thinking of the very controversial and widespread use of drones.

Now we are into normative issues…

Yes, this analysis definitely brings us into normative research. But it is also about the communication of normative research – to tell others what different traditions and arguments say, and to use that critically in politics and in the armed forces. I have lectured in many military settings, often to soldiers. There, I very consciously communicate something normative.

Once, I got a compliment from an officer after I had spoken to soldiers and officers who literally the next day would depart for Afghanistan. This was after some soldiers who had been in Afghanistan infamously had said to a Norwegian magazine that they used expressions like ‘going to Valhalla’, and that it is ‘more fun to kill than to have sex’. The officer said to me, several years later, that he appreciated that his company heard my lecture on the last evening before leaving. He could later use words and expressions from my lecture when speaking to the soldiers in Afghanistan. He told me something along the lines of: ‘We spoke about virtues, not about Valhalla. We talked about who we are, what we are proud of, and how we can live up to our duties, as duty ethics requires of us, but not just for the sake of the duties per se, but so that we can act in accordance with our virtues, with who we want to be.’ He could use this kind of language partly because I had spoken to them the day before they left. That makes me proud to be a philosopher.

Back to your question. Yes, I am normative on behalf of a common foundation: international law, the Geneva Conventions, proper behaviour in war, but also on behalf of basic ethical ideals that call upon us to take good care of each other, and to be honest and caring even when the surroundings are tough.

You know this, as a theologian – that some sermons can be academic in the sense that you want to convey something you have read and used your intellect to understand, and that you therefore want others to learn or understand. At the same time, you want them to think about right and wrong, and give them something to build their lives on. In that sense, I am more of an Aron from the Old Testament story, the priest who could speak, than Moses, the great leader who brought his people through the desert. I am the one who teaches more than being any kind of prophet – or great thinker.

Being at PRIO and meeting people like Nils Petter Gleditsch, Scott Gates, Pavel Baev, Greg Reichberg, Torunn Tryggestad, Inger Skjelsbæk, Hilde Henriksen Waage, or Marta Bivand Erdal, to mention only a few impressive scholars – I could have mentioned so many more – I realize that I am probably not in their category with regard to original thinking. But I may be able to communicate deep thoughts and important teachings. I like that. I like being there between the normative and the research-based, between thinking and communication.

Priests and Prophets

And that reminds us of the relationship between a priest and a prophet.

Yes, the priest has a different role than the prophet. Yet both have to speak the truth.

And it is only afterwards one can see whether someone has been a prophet. One cannot appoint oneself.

That is true. One should be on one’s guard once someone claims to be a prophet.

So, maybe it could happen that you, in your role as an academic priest, sometimes will be thought of as a prophet?

That was generously said. I myself do not believe that. But I believe that I can be among those who say things that people afterwards realize are important. That is the most satisfying thing about being a teacher: that I can communicate things that I know people may be thinking of twenty years later. We should challenge each other. Not everything should be like sweet honey to the ear – or is that the right expression? Well, what I mean is: not everything should be swallowed without friction.

I teach at Bjørknes University College here in Oslo, which PRIO has had a very fruitful collaboration with. There, I often use old texts – say, excerpts from Plato’s Republic, or his first Alcibiades dialogues. In the room I have 10 or 15 students who never thought they would be reading something like this. Suddenly, there are one or two whose eyes are opened. They see something they had never thought of. Some of them may even continue with studies or at least readings in philosophy. To introduce young men and women to that – well, that’s when I realize this work is certainly worth it.

Do you read the Biblical Book of Joshua?

No, but maybe we should. I remember it from my own reading of the Bible. Not least what happens after the fall of the walls of Jericho. We do sometimes discuss the ambivalence in how religious texts treat war and peace. Religious texts can be used as recipes for how to live, detached from their contexts in the wider bulk of texts or in history. That can be dangerous. What we must search for is, so to speak, the hermeneutical common thread – or the red thread – through these texts or scriptures, describing a movement from this world of chaos to the persons we ought to be and the world we should fight for. That is so crucial to biblical hermeneutics.

Or is it possible to use the Book of Joshua as a recipe for how not to behave?

It is like many biblical texts. You fight with them, and they portray the negative as well as the positive. Think of King David – placing Uriah in the front line so that he would be killed. David could then take Uriah’s wife, Bathsheba, as his wife. At the same time, he is one of the heroes in Jewish and Christian history. That is the nature of these kinds of texts, written by people with different impressions and purposes. That holds even if we believe the texts are divinely inspired. This is why critical reading of religious texts is so important.

Gender

So, generally it is men who wage wars, and also write about the ethics of war and peace. Do you reflect on the gender dimensions of what we are discussing?

I am forced to it. For different reasons. First, because I am privileged to be at PRIO, where gender research plays an important role. I have participated in some of it. I have learnt a lot, especially from people like Inger Skjelsbæk and Torunn Tryggestad, as well as Helga Hernes, who for several years was my dear office mate. I have learned that much of what I have taken for granted – why things are as they are, why some people have power and others not – are related to gender in some way or another. I have learned that one acts, consciously or unconsciously, in accordance with expectations that are related to one’s gender. Think of the Middle East, and how many of the conflicts there, or in other places, are about – not only, but also – alpha-males trying to demonstrate how strong they are.

One of the things I do like most about the gender research here at PRIO is that it is so empirically solid, and therefore does not become primarily political or ideological. The gender researchers have also cooperated with and learned from the armed forces. My wife has actually been part of that, as senior adviser on gender issues in the Ministry of Defence, and that is a second reason I have been preoccupied with this. I am confronted with gender issues at home, intellectually and practically! Hanna and I even have four daughters!

This of course brings us to texts again, and to those who have written them: men! I remind my students that there are lots of people whose stories we simply do not hear or hear only indirectly. People who may have been great thinkers in their time. They may have had influence, but we do not read their thoughts directly because they did not write or take up leading positions. Their voices are not always readily available to us; we have to dig them out.

In an anthology Greg Reichberg, Endre Begby and I edited about the most important texts on war (The Ethics of War: Classic and Contemporary Readings, Oxford, 2006), we found a text by Christine of Pizan from around the year 1400. It is one of the best summaries of the ethics of war of that era. One of the things widows could do in order to have an income was to write. This was recognized and acknowledged. Usually it was poetry. Christine of Pizan decided to write about knights and war. For centuries, however, the structure of societies was such that women could hardly make themselves heard.

The next question is whether there is something essential with men, biologically, which makes them behave differently from women, and whether war and conflict are grounded in this. I am agnostic about this. It is a complicated area, filled with different viewpoints. We need wide and open debates about these issues. But above all, the turn to gender research as part of research on peace and conflict is important and right. It is a weakness in the tradition that there are too few female voices. There is no doubt about that.

Yes, and people such as Dennis Mukwege in the DRC show us very clearly how sexualized violence becomes a weapon of conflict.

Indeed. And that is what I remember from when I first met and discussed this with my good colleague Inger (Skjelsbæk) from my early days at PRIO: how sexualized violence has become a permanent feature of many wars, making it essentially into a weapon. It can be used as a deliberate war strategy, and it can be perpetrated with varying motives amid the brutality of war – amongst civilians, the military, and also peacekeepers. Whatever the root causes, conflict-related sexual violence is a real and powerful weapon.

This is important to us in the Nobel Committee, since we are committed to Alfred Nobel’s will, which speaks of disarmament. I am of the opinion that the fight against sexualized violence in war is to fight for disarmament, since sexual violence is a weapon of war. This is what we also said in the announcement of the Committee when Mukwege and Nadia Murad received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018. It is about reducing violence and abolishing a kind of weapon. Mukwege is one of those who has formulated this most clearly, in a way that builds on the realities of war.

But then, we are on our way to your role in the Nobel Committee. And Bertha von Suttner..

That is exciting …

… she is one of the prophets of the 19th and 20th centuries, right?

Yes. This is interesting since most of those who have done research on the life of Alfred Nobel agree that the Peace Prize would never have been instituted without her pressure. He was impressed and fascinated by her. They met only a few times, and we can sense that their relationship could have become closer, but it did not. On the other hand, the correspondence between them, not least her reports about contemporary discussions about peace, made a great impression on him.

After her time, women have had an increasingly important voice in political debates, and thereby have had a lasting impact on efforts to democratize our societies. This was important for the peace prize and peace work more generally. Bertha von Suttner saw and experienced that women do have an important and legitimate role in what at the time was known as peace congresses.

The Nobel Committee

Let us continue with Nobel. How is it to be at PRIO while at the same time a member of the Nobel Peace Prize Committee?

As an academic, it is fantastic. It is like a hand in a glove. When I do my work for the Committee, it feels like continuing my daily work. I have to read a lot, and I never do that particular work at PRIO in order to keep to strict confidentiality rules. So, I do that at home. Lots of papers to read and demanding discussions – that is the essence of the work in practice. But through this, I am certainly enriched as a researcher. To people on the Committee who do not have the kind of day-to-day work I have, it is probably very demanding. On the other hand, it is good that not all members are specialists on international politics or do research on conflicts.

My membership has not caused any problems for me at PRIO. Before I said yes to the parliamentarians of the Conservative party who nominated me, I discussed it with my wife, my brother, and another good friend, plus with Kristian Berg Harpviken, who was then PRIO’s director. Kristian had no objections. I discussed it with him to be sure that it was not seen as problematic that a PRIO researcher sat on the Committee. He established a policy, which is still available on the PRIO Home Page, a ‘disclaimer’ which has functioned well – for him and for his successor, Henrik Urdal – and which says that there is no contact between my work on the committee and any of my PRIO work or my PRIO colleagues. I can only tell them about the prize after it has been announced – and then I can only say what is said publicly to justify the prize. And let me add: read that announcement carefully. There, in the details, you will find our justification.

Beyond that, I can say very little. This is the way it has to be. In short, I have to be very careful. I’ll admit that the double role as a member and a peace researcher is not always without problems. The discussions in the Committee are not publicly available, and we do not tell who has been nominated or not. But of course, I give lectures on peace-related topics and meet many people all the time. I meet people from, say, Iran or Iraq the one day, Americans the next, and can be invited to a meeting in the Middle East the third. People look at my CV and discover that I am the vice chair of the Nobel Committee. Then they probably start interpreting things I say or hear what I say in light of my Nobel affiliation. This is unavoidable, so I have to be very conscious about what I say and do not say. However, I cannot and will not stop talking about foreign policy. If so, I could not do my job. Let me add that I feel extremely humble about being at PRIO and being a member of the Nobel Committee, because there are so many PRIO colleagues of mine who could and should have been on the committee rather than me. Goodness, I mean it, and it makes me so humble.

A Sunday School Teacher

We are approaching the end. And let me mention, you are also a Sunday school teacher in your local church. Maybe the most famous Sunday school teacher in Norway.

That is kind of you to say. There are many who are involved in Sunday school work. I have had the fortune to be known as one because I sometimes speak about it.

What is then the link between your work here, as a peace researcher, and Sunday school?

There is no historic link here. Hanna and I came back from the US, and one Sunday we’re in our local church. During the service, they asked if there was someone who could help with Sunday school. We did not have children at that time, but, perhaps because of that, we could do it. This has nothing to do with PRIO. But I have found that there is a connection, both there and when I travel the country to give lectures or addresses. The connection is in my eagerness, as a researcher, to communicate insights to people outside our professional circles – to people who will never read what we write, who think that discussions among researchers are almost incomprehensible, but also deserve to hear what we believe is important. This is interesting and pedagogically challenging.

What I like most about Sunday school is to explore how complex issues can be communicated in such a way that children understand them – and especially, to link ethics and metaphysics. Metaphysics at its best tells us that your life and the lives of others are worthy and wanted. And Sunday school is about Bible texts, about understanding the world as created and multifarious – in short, about metaphysics. But it is therefore also about ethics: let us protect this diverse world and all those in it.

What I like most about Sunday school is to explore how complex issues can be communicated in such a way that children understand them – and especially, to link ethics and metaphysics. Metaphysics at its best tells us that your life and the lives of others are worthy and wanted.

I also emphasize that Jesus gives extra time to those who are on the outside. This is an incredibly important aspect of the New Testament texts. We are responsible for each other, and God is present as part of this world, even – or maybe especially – for the outsider. The underlying message is that the day you feel that everything is difficult, you are still not alone. I try to communicate this, while also avoiding making it just sweet and harmless – because this should challenge us.

So, there are indeed links between this and your peace research?

Yes, obviously. Well, not programmatic ones. In other words, I do not try to be a Sunday school teacher where I should not be one, and I am not a peace researcher in Sunday school. Fortunately, on that score, I very seldom meet people who are angry with me about mixing roles, but rather I often meet people who say: ‘Good for you that you are a Sunday school teacher.’ Through this, I think I bring my lectures and what I talk about closer to people. There are many who will say: ‘I did not even know that Sunday school still exists. But I remember I went to Sunday school, and there was this flannelgraph.’ Yes, we have one. Fine thing. Flannel cloth on which you can hang figures. Cute. Takes away distance. People can be a little nervous if they know I am a peace researcher, and a member of the Nobel Committee. But I am also a Sunday school teacher! That is less frightening.

Let me add, though, that I have deep respect for those of other faiths – or of no faith. I realize that we live in a world where many find faith to be problematic or strange. I do take that seriously. And also, I am often afraid that talking about faith can give the impression that you think you are somehow more holy and ethical than others. I am deeply humble about my own shortcomings and my own mistakes. I am sure there are people I have hurt or wronged in my life, as well as academic mistakes I have made. Being a person of faith only makes me more regretful and humble in the face of that.

A last question linked to what we have talked about. I know you are writing a book on ambivalence and ambiguity?

Yes, very exciting stuff. This effort is born out of a philosophical and indeed ethical observation: namely, that in the most difficult questions we face, there are important arguments on both sides of a debate. Think of abortion, or for that matter, war. To insist on certain principles and the struggle to avoid relativism must not be the same as saying that one side is completely right, while the other is completely wrong. It is only through dialogue that we can find solutions, and very often compromises.

22nd of July 2011

This book, which I hope to finish in 2020 or 2021, was born out of another project, about the terror that happened on the 22nd of July here in Norway. Two colleagues, Rojan Ezzati and Marta Bivand Erdal, wanted to apply for funds for a project, and they needed someone with a doctoral degree to stand as project leader and sign the application. They asked me and said that I probably did not need to do that much in practice, because it was already a well-staffed application. We composed a solid application, really, had several people from other institutions joining in, but frankly, I did not expect it to go through, because it was a brand-new project and it competed against so many others. But we got the funds – for four years. One of my tasks in the project was to formulate questions about the freedom of speech, the responsibility for speech, and how to combat extremism in light of the ideology that informed Breivik’s actions.

To know when you should be ambivalent, and when you should not, is one of the most important things in this world. To be able to say that there is a moral boundary, that we cannot accept certain actions, but at the same time that we must have freedom of speech.

I learned then that that to know when you should be ambivalent, and when you should not, is one of the most important things in this world. To be able to say that there is a moral boundary, that we cannot accept certain actions, but at the same time that we must have freedom of speech. In the upbringing of children, we must make it clear that there are absolute boundaries for what we can do and say to others. But we have to combine this with an open and generous space for speech, a room where we listen and see nuances. One of the articles I wrote for the project was for a conference on Vaclav Havel’s life and thoughts. When should we be open and ambivalent, and say, ‘Well, maybe I am wrong?’ And when must we stand firm and allow for no compromise? I believe this is a key normative question, and even a question to us as researchers: what should we engage with? What do we need to take seriously? The name of the project was ‘NECORE’, short for ‘Negotiating Values: Collective Identities and Resilience after 22nd July’.

It is good to finish our conversation by talking about this project. Some time ago, I met some of our veteran researchers in the PRIO lobby. We talked about this place and said to each other that this is a good place to be. I am truly grateful for that. And now, I am learning from the younger researchers. Those who are born ten or twenty years after me. It is so good to learn from people who have read, understood, and talked about things that I have never heard or seen. NECORE has been truly educational for me. It has contributed to my humility – fortunately not humiliation, but the opposite, humility. That is very good.

And this is how it is possible to take up a clear position and at the same time question things?

Yes, I hope so. I believe that what we experienced on the 22nd of July and also during the recent terrorist incident in our neighbouring municipality of Bærum (a failed attack on a mosque) demands of us that we are principled and clear about human dignity. At the same time, research has an extremely important role in asking open, curious, and critical questions. I thrive in that position, at least as long as I can occupy that position together with my wonderful colleagues.

Then all that remains to be said is: Thank you!

And from me: Thank you for very good questions!