Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash

At the time of writing in early May 2020, Norwegians have in many ways escaped lightly from the first phase of the pandemic. The outbreak was contained at an early stage, the number of cases is low and there have been few deaths. In addition, Norway has money in the bank to secure basic welfare for its citizens. Internationally, Norway is being presented as a success story. We have now entered the re-opening phase.

Coronavirus and the constitutional state: a socio-legal starting point

To a large extent, this success is founded on two concepts central to Norway’s coronavirus vocabulary: “trust” and the Norwegian word “dugnad”, meaning organized voluntary work undertaken collectively for the greater good. A combination of high levels of social trust in the constitutional state and in our fellow Norwegians, and the successful mobilization of a national dugnad spirit, have been important prerequisites for Norway’s emergence from this first phase relatively unscathed. Although the concept of dugnad is not in itself uniquely Norwegian, effective use is made of the concept as though it represents something uniquely Norwegian.

However this mobilization has also enabled encroachments – and omissions – and initiated processes that should cause us to feel a certain discomfort, and to cast a critical gaze on the period we are now leaving behind. As the American sociologist Craig Calhoun has observed, when one has declared something to be a crisis, then this defines not only who should do something, but also what they should do. The focus on urgency, on the fact that something must be done quickly, shapes our perception of what is happening in the world, what kinds of alternatives are available, and what kinds of compromises are justifiable (see ‘Humanitarian action and global (dis)order’ in States of Emergency pp. 29-58).

From a socio-legal perspective, this result means that we should be concerned about how the law influences society’s response to coronavirus. Our concern should extend to the law’s intended, unintended and concealing effects. The initial proposal for the Emergency Powers Bill drafted in secret and presented on 19 March, entailed a comprehensive transfer of power from the Storting (the Norwegian parliament) to the government, with the objective of bypassing existing legislation and adopting temporary regulations to adapt the relevant laws to “coronavirus measures”. The proposal provoked an uproar: lawyers, civil society organizations and academics expressed scathing criticism. The following week, the Storting voted unanimously in favour of a heavily amended law. The government has continually emphasized that there was no intention to deviate from human rights legislation. But how the coronavirus regulations restrict citizens’ material and procedural legal safeguards, and possibly their human rights, is an empirical question, which should be analysed by applying our toolbox of qualitative and quantitative research methods.

At the same time, we must investigate how the management of coronavirus has affected the law (see Retten i samfunnet: en innføring i rettssosiologi by Thomas Mathiesen). We must investigate how the coronavirus pandemic, as a shaper of opinion and a materially new factor in need of rapid regulation, affects fundamental constitutional principles, such as legality, the rule of law and legislative processes. A good candidate for investigation is the Smittestopp (‘Infection Stop’) app.

Smittestopp: Fear, consensus, trust and haste

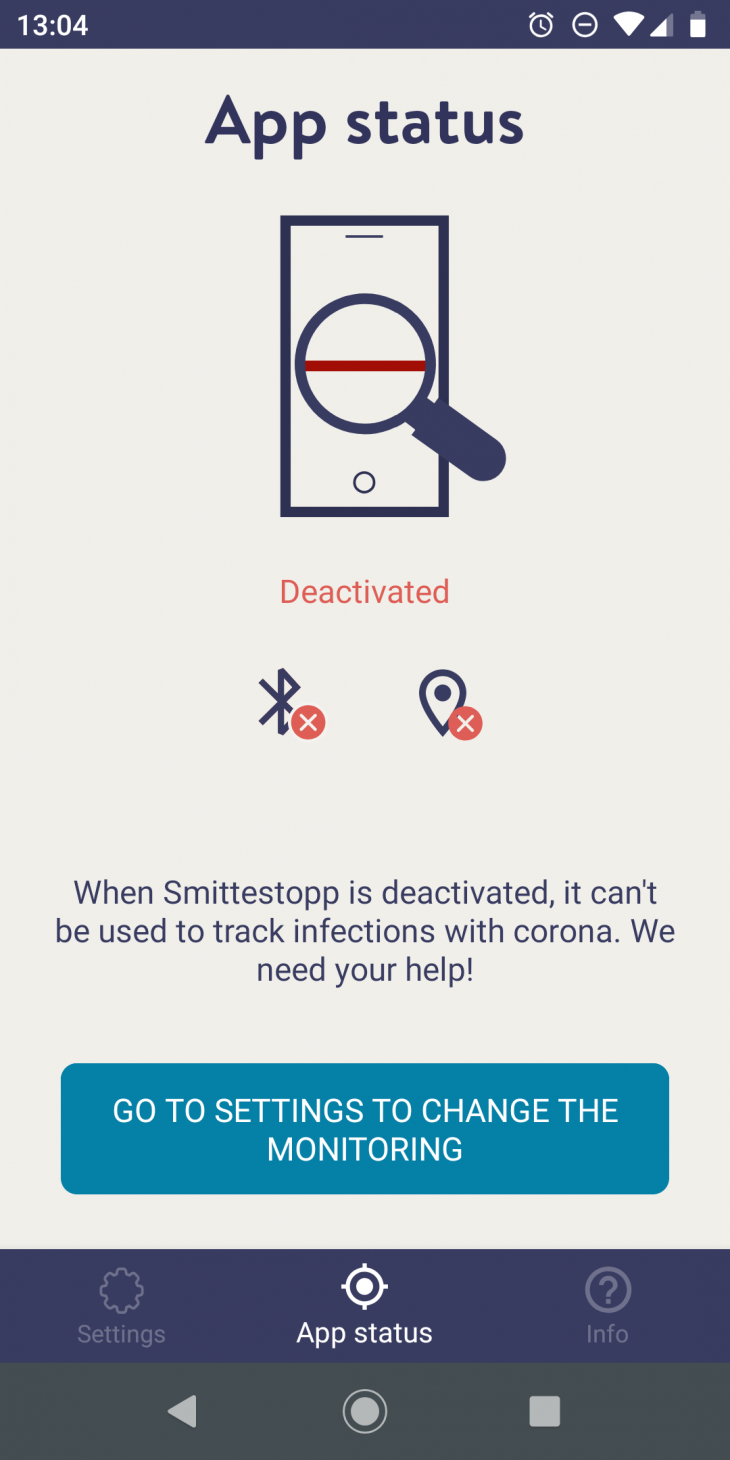

On 16 April, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (FHI) and Simula, the app’s developer, launched Smittestopp. According to the FHI, if you have downloaded Smittestopp, you will receive an SMS alert if you have been in close proximity to another app user who has tested positive for coronavirus. The alert will contain advice about how you can take care of your own health and protect others against infection.

Norwegians are enthusiastic and trusting users of commercial and public-sector digital services. By the end of April, 1.5 million Norwegians had downloaded the Smittestopp app, and as of 28 April there were 899,142 active users. Nonetheless, on 7 May the FHI announced “[we] need more Smittestopp users”. By mid-May, the app still had not found anyone infected – but collected billions of GPS positions.

One important issue to investigate concerns the relationship between trust and the extreme haste with which Smittestopp was developed and then launched as an unfinished product to the Norwegian population.

Many countries have implemented, or are now experimenting with, contact-tracing apps. It is important to be aware that the technology used for Smittestopp is not the only possible solution for a contact-tracing app. Smittestopp is being promoted according to a well-known cultural repertoire that there is good reason to examine with a fine-tooth comb.

One important issue to investigate concerns the relationship between trust and the extreme haste with which Smittestopp was developed and then launched as an unfinished product to the Norwegian population. Another issue concerns the fundamental principle involved in the fact that the state now wishes to conduct surveillance over its citizens in a completely new and invasive manner, with little if any critical push-back from import parts of civil society.

To contribute to comparative analysis of digital technology in the COVID-19 response, this blog post roughly categorizes the objections to Smittestopp.

Chaotic procurement, an unfinished product and security issues

In Norway, legal conflicts between the state and its citizens are often resolved by (re)directing the discontent into formal, bureaucratic complaints procedures. Many people are discontented with the way the app was developed: Simula contacted the FHI under its own steam and landed a contract worth 16 million kroner – the app costs NOK 45 million in total. The procurement process, or rather the lack of one, is already the subject of a complaint to the Norwegian Complaints Board for Public Procurement (KOFA).

The code behind the app has not been open-sourced, provoking criticism from members of the tech community, who believe that collective stress-testing – basically a kind of hacking dugnad – of the app’s security could have been better. Security experts have demonstrated cybersecurity problems and a potential issue with fake SMS alerts – in other words, SMS “spoofing”, where both the sender’s name and the content of the SMS are manipulated – either for fraudulent purposes or simply to scare the recipient.

Other countries have rejected this approach (or tracing apps as a public health response in general), not only because it has been thought to be ineffective, to generate “false positives”, and to have connectivity issues, but also because of the relatively invasive nature of the continuous surveillance.

A screenshot from the Smittestopp app.

Unclear communications about legally invasive objectives

The legal basis for the app is the Communicable Diseases Act and its subsidiary Regulation relating to digital contact tracing and epidemiological controls in connection with the outbreak of COVID-19 (LOV-1994-08-05-55-§7-12, LOV-1994-08-05-55-§1-2). Communicating the law is key to ensuring that a law or, in this case, a regulation, is effective. For a member of the public, using Smittestopp and understanding what such use entails requires a high level of “techno-legal consciousness”, i.e. a combination of technological understanding, awareness of one’s rights, and an understanding of risk (see “Technology, dead male bodies, and feminist recognition: gendering ICT harm theory” by Kristin Bergtora Sandvik). For its part, the government has focused on various combinations of dugnad spirit, freedom and voluntariness as means of promoting the app.

For a member of the public, using Smittestopp and understanding what such use entails requires a high level of “techno-legal consciousness”, i.e. a combination of technological understanding, awareness of one’s rights, and an understanding of risk

While the government has been at pains to emphasize that data will be deleted after 30 days, it has been less eager to explain that the app’s other objectives are research-related and that the anonymized data gathered for research purposes has a completely different life expectancy. According to Section 1 of the Regulation, its purposes – and those of the app – are to “assist in rapid tracing of, and provision of advice to – persons who may be infected with coronavirus SARS CoV-2.” Through monitoring at population level, the Regulation will also contribute to tracking the extent of contagion and evaluating the effectiveness of infection-control measures. Under “Section 6. Deletion of personal data”, we read that “location data shall be deleted after 30 days. When a user deletes the app from their mobile phone, all personal data about the user in the contact-tracing system shall immediately be deleted or anonymized.” Initially, this means that the data are not deleted, at least not in the sense that the average person understands “deletion”. In a situation such as that in Norway, with a relatively low number of coronavirus cases and relatively limited testing, this procedure also raises major questions about anonymity and identification. The Norwegian Data Inspectorate has already expressed concern about the app and continues to monitor the roll-out.

“Will it work?”: effectiveness and effect

Serious doubts have been expressed about whether the app will actually work. In other words, whether it will provide useful information to users, in the form of SMS alerts. Contact is not the same thing as infection. What should one do if one gets an SMS alert about contact? The app is still undergoing testing. Norway is in the process of reopening without Smittestopp.

The question of effectiveness is however scarcely the most interesting issue here. There are the questions about effect: what effects will the app have, not only from a purely technical perspective but also from the perspective of interpersonal relationships?

It is also important to direct critical attention to the consequences of the app for legal safeguards of technical changes in official recommendations about social distancing: a sudden change in the recommended distance from 2 metres to 1 metre pulled the rug out from under a recommendation to reduce the number of associate judges in court. If one changes the threshold for a Smittestopp SMS alert from being within 2 metres of an infected person for 15 minutes to being within 4 metres of an infected person for 5 minutes, the app will “generate” many more useful alerts – and also gather and link far more data.

At the same time, Smittestopp continues to generate location data concerning patterns of movement in the population.

Smittestopp as the problem

There is always a danger that a combination of fear and consensus will result in poor judgement. From a socio-legal perspective, we must also investigate questions about the freedom of the individual versus the collective in a dugnad context. While it is important to determine whether the technical aspects of the procurement process and the data-processing aspects of Smittestopp were legal or not, even if they were legal the fact remains that the app represents a quantum leap in willingness to conduct surveillance over everyone living in Norway. Every day Norwegians allow their digital bodies to be generated, invaded and controlled by multinational tech giants such as Facebook and Google (see “Making Wearables in Aid: Digital Bodies, Data and Gifts” by Kristin Bergtora Sandvik). The fact that it is now the state that is responsible for this invasion – by means of a mobilization based on trust and the dugnad spirit, an unsatisfactory procurement process, an unfinished product that may or may not work and apparently lacking thorough analysis of risks and consequences – makes Smittestopp an innovation that is “disruptive” also to fundamental constitutional values.

The government emphasizes strongly that downloading Smittestopp is “voluntary”. Nevertheless, prime minister Erna Solberg has said: “Personally I think that if we are going to get back our normal lives and freedoms, as many people as possible must download the app”. Commenting on the massive skepticism and criticism the app has encountered, Solberg has said: “I have respect for people’s feelings, but the fewer that participate, the longer the time there will be more stringent measures in other areas.” On the day the app was launched, the FHI tweeted “Hi folks. There are lots of people wanting to download #smittestopp right now. If you are unsuccessful, try again later. And thanks to all of you who want to take part in our dugnad in this way too.”

Perhaps we should instead be discussing how using the app restricts one’s freedom. Additionally, what happens when the type of surveillance conducted by Smittestopp becomes normalized, and participation is expected as part of one’s civic duty? Time – and socio-legal research – will show what kind of problem Smittestopp actually represents.

- This piece was originally posted at Sosiologen.no You can read it by clicking here.

- Translated from Norwegian by Fidotext

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this piece stated incorrectly that “Simula … landed a contract worth NOK 45 million.” This has now been changed to clarify that the contract was 16 million, and the total cost was 45 million.