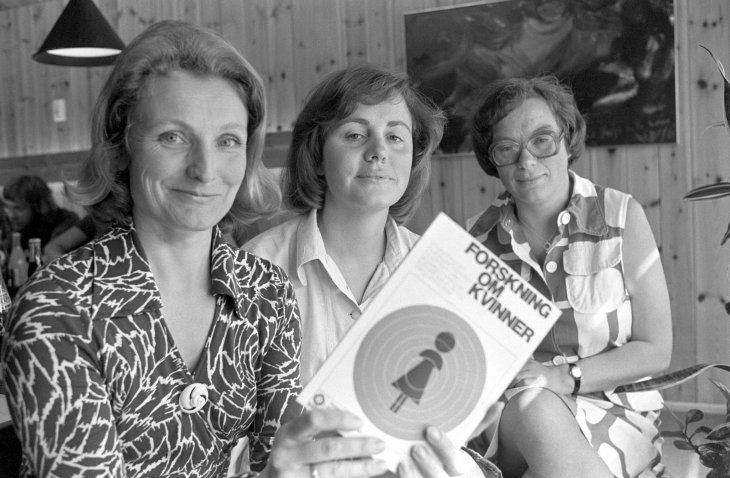

From left: Assistant Professor Helga Hernes, Lecturer Hanne Haavind, and Mari Holmboe Ruge from the Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities (NAVF), working on the study Research on Women in a committee under the Council for Social Science Research, 21 June 1976. Photo: NTB Scanpix

Mari Holmboe Ruge, interviewed by Kristian Berg Harpviken

Mari Holmboe Ruge’s life has been guided by the radical vision of a peaceful world, and a pragmatic conviction that robust organization is the key to achieving it. Mari played a critical role in PRIO’s first decade – analyzing, administering, advocating – to build the foundations for a knowledge-based global order. She later held posts in research funding, research policy, and research administration, where the same basic commitments prevailed. Throughout it all, in parallel to her professional career, Mari has been actively engaged in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF).

Born on 20 July 1934, Mari was a child of 11 at the close of the Second World War. During the war, her father was a leading figure in the non-violent Teachers’ Resistance. Her future husband, Herman Ruge, became a conscientious objector despite descending from a family of military officers – as did Johan Galtung, who was a close friend of the family and a prime force in founding PRIO.

Interviewing Mari Holmboe Ruge at her home in Oslo on 19 December 2018, I sensed the contours of a radical student collective, rooted in networks of family and friendship, and highly active in the debates of the Norwegian Students’ Society. It was this collective that became the core of PRIO.

Kristian Berg Harpviken: Thanks, Mari, for agreeing to be interviewed. I have looked forward to this conversation – more so the more I have read up on your career. It is really exciting to get to talk to you. You played such an important role for PRIO during a critical period.

Mari Holmboe Ruge: Well, of course. Looking in the rear-view mirror one does of course realize that, doesn’t one? I have also been thinking about how it was the very first job I ever had. And I hadn’t finalized my studies, either, when PRIO was founded and I started there.

I understand. But I had thought that by then, you had completed your studies at Columbia University?

I did depart from Columbia that same autumn. Herman and I both got one of these Fulbright scholarships to take a year in New York. He was at the physics lab there, he got a minor assistant post at the lab. He had completed his cand. real.[1] exam in physics and had already worked at Sentralinstituttet for industriell forskning (the Centre for Industrial Research) on the emerging science of automation. I had not completed my studies. I had taken geography and started with French, which I put aside because I didn’t like it, and I planned to pursue studies in history. But then things happened and I took sociology, still a young discipline at the time.

And then there was this opportunity, so we left on the America boat in 1958, during the summer, and lived there until the following summer. There, we rented a room in the university flat that Johan Galtung and Ingrid Eide had, right by campus. We moved twice, but stayed in that area.

I started my master’s in sociology. You know, when one is in the middle of it… Later, you realize that the teachers you had are the ones that appear in the footnotes and that sort of thing. Then there was Otto Klineberg,[2] and there were a few people like that, I didn’t really understand who they were… then, wow, there he was! And then that autumn I got pregnant and my eldest daughter, Lotte, was born on 22 August. I had to return by boat because they did not allow me to fly. So, I got home around 1 August, and she was born on the 22.

And then I started [at PRIO], in fact, could it be on 1 November? It was quite… I hadn’t finished by then, hadn’t completed my thesis as I should. I only got around to doing that the following year, when I completed my master’s degree. So, I was still a student when I began working at PRIO under the wings of Johan.

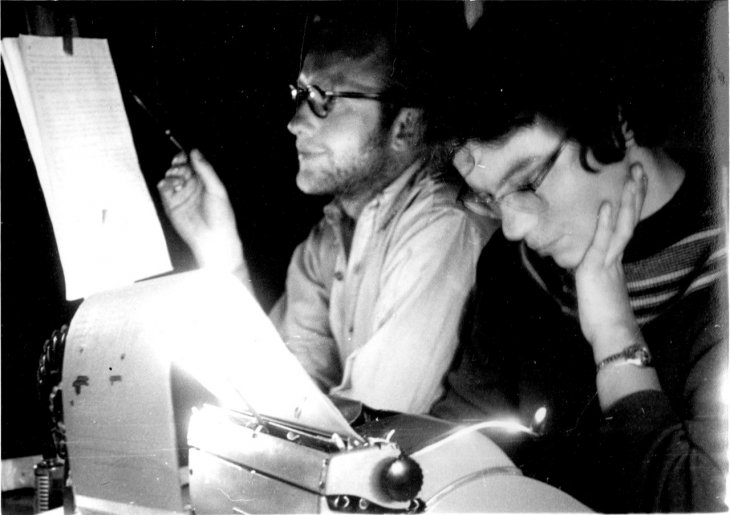

Johan Galtung and Mari Holmboe Ruge working at PRIO. Photo: Ruge’s private archives

So, what was the topic of your dissertation, then?

It consisted of a content analysis of racial conflict in the United States. We went on fieldwork to Charlottesville, which today is remembered for the white supremacist demonstrations in August 2017.

[My dissertation] was a content analysis of racial conflict in the United States. We went on fieldwork to Charlottesville […] At Columbia’s sociology department there was a, if not radical, at least liberal environment. I can’t recall that there were any black students among us though.

At Columbia’s sociology department there was a, if not radical, at least liberal environment. I thought it was nice to be a part of that. I can’t recall that there were any black students among us though. I can’t… I have never thought of that before, but I don’t believe there were.

So, there you see. We lived in New York’s 118th street, close to a steep park, which we had to walk through to get down to Harlem. And, on the southern side of campus, you found the Puerto Rican quarter. But around Columbia? The people living there seemed all to be descendants of European Jews, wasn’t that so? We didn’t live in Harlem but we spent some time there. And we went there for shopping, and I noticed that in almost all of the shops the shopkeepers were white.

We knew very little about what kind of society surrounded us, but I can’t remember that I ever found it unpleasant. Once, I forgot my handbag in one of these drug stores where we had been sitting down to have a bite. When we returned three hours later, it was still there, and it contained everything we possessed in this world. I remember our stay there as a very positive experience.

Were you satisfied with your studies there?

Yes. But it was very course-based. A lot of statistics. I do not now remember much of the actual content. But there was a lot of learning by heart. The courses were not supposed to lead to a PhD. Like I said, we returned home late in summer, when Lotte was born.

Mari Holmboe Ruge, pregnant with her child Lotte, and her husband, Herman Ruge in New York, July 1959. Photo: Ruge’s private archives

The Pioneer Years

By then, did you already know Johan well? Did the two of you go home at about the same time?

He and Ingrid had gone home already the year before, after their son Andreas had been born. They had not planned to travel home with a newborn, but it didn’t quite work out as planned. Andreas was born three weeks early, on 6th December. They got home by Christmas, with the baby in a bag. And they surprised all the grandparents, who had no idea that a child was on its way.

And we came home the following autumn, or summer. Our friendship with Johan went far back. While Johan and Herman were two years apart, they had both attended Vestheim high school, and their parents knew each other. General Otto Ruge [1882–1961], the brother of my father-in-law, was a very close friend of Johan’s father. Yet Johan and Herman only really got to know each other at university. They were fellow students, but I don’t think they were ever friends during their school days.

And they both studied mathematics?

Yes. Herman became a physicist, and Johan was also a mathematician. This must have helped them get to know each other so well. Ingrid and I had met each other during our school stays at an international school camp (skoleleir), which Ingrid was involved in organizing.

So Herman and Johan, and you and Ingrid, knew each other independently?

Yes, we did. So we were friends from earlier. That was also the reason we ended up accompanying them to New York. And surely also the reason I found my way to sociology. That wasn’t something I had been thinking about before.

And sociology was a young discipline in Norway in 1959, wasn’t it?

It was, and what brought us to it was our general interest in international issues. We had all – I am sure you have too – written essays on how the world could become a better place. My father was an engaged teacher (skolemann).

If we move forward to 1958–59, how did PRIO come into being, the way you see it? You were in the midst of it, present at its creation.

Yes, I was in the midst of it. I had not however had any contact with the Rinde family, who made it possible financially. I came in as a research assistant for Johan. And that became a part of my everyday life.

Were you recruited already during your stay in New York?

Yes, in fact I was. He was very eager that I should start as soon as possible. But my child was, as I said, born on 22 August, and then it became…

I realize this was anything but an extended maternity leave?

No, as you can understand, it was not. And we did have some scholarships and some other arrangements, but then Lotte’s sister Ellen was born on 1 December 1960 – in other words, only 15 months later. So, if I have been somewhat hesitant to talk about all of this, it is because it was a rather exhausting period. I may have subdued – no, not just ‘may’, I really have repressed a lot of this. I have been thinking: how did we manage? There were no kindergartens. We had a nanny, who came to help, and I worked part-time. At that time, we were out at Lysaker, and that was also rather cumbersome.

If I have been somewhat hesitant to talk about all of this, it is because it was a rather exhausting period. […] I really have repressed a lot of this. I have been thinking: how did we manage? There were no kindergartens.

You were at Polhøgda?[7]

Yes, we were at Polhøgda. In reality, I had the sense that it was a continuous hurdle race where you always had to be on time for this or that.

It is the case, I guess, with all pioneer projects, that there is no limit to how much time you can invest.

It is very much like that, isn’t it? And Ingrid had Andreas, who was eight months older than Lotte. Ingrid spent a lot of time at the office. Amongst other things so that she could breast-feed him. This is how our children became siblings forever. They have become very fond of each other and have a lot to do with each other, as siblings and friends. And that is very nice. So, our collegial friendship was passed on to a new generation.

My days at the time were by and large taken up with reading proofs, calculating coefficients, things of that sort. It was meaningful in a way. And, with time – because Johan and Ingrid travelled a lot – I was the one who was present. I went to lots of our conferences. They lived abroad, which I couldn’t and really didn’t…

So, they had long stays abroad, the two of them?

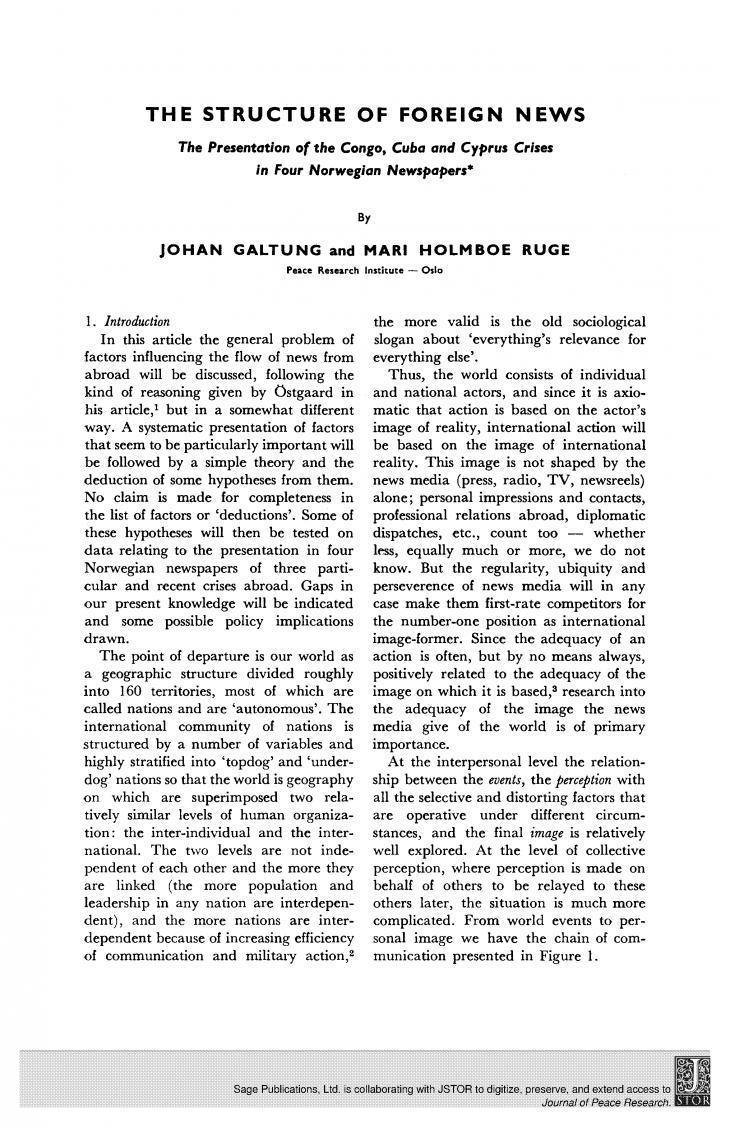

They lived in Chile for quite a period. That is where I know they stayed the longest. But their second son, Harald, was born in Morocco. They were away a lot. And I, well, we didn’t have an institute secretary or anything, so that was very much the role I took on – a role that somebody had to fill. In addition, I did a number of other things. In terms of research, I worked on content analysis, with categories and things like that. My thesis, as I said, was based on that. And then we wrote the much-cited article in the Journal of Peace Research on the ‘Structure of Foreign News’. I checked: I was googling a little yesterday, and then I saw that – oh wow, it is really everywhere!

Johan Galtung & Mari Holmboe Ruge (1965) ‘The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers’, Journal of Peace Research 2(1): 64–90.

It’s important for me to say – because many things can be said about Johan, and we will not spend much time on that – that in those situations he was, which was remarkable at the time, extremely generous. He included me as a co-author. What I had done was the groundwork, to examine the data, tick off boxes, things like that. Yet he did include me as a co-author!

So, you did much of the coding?

I did all of the coding, we didn’t have anybody else who could do that. He didn’t need to include me as co-author, but he did.

You also collaborated with US researchers, didn’t you? With [J. David] Singer and others? On US-funded projects? I have noticed that you co-authored several articles.

Yes, that was the way, and that was how it had to be. I learned the discipline much more thoroughly that way, didn’t I? So, I have benefited greatly as well.

Then there were lots of people coming to Oslo, as well, in order to be part of the new environment?

That is precisely what happened. I don’t know what others have said about this, but people came to Oslo because they wanted to work on the topics we were working on. So, because we are back in the 1960s and early 1970s, the political agenda was at the forefront. It is significant that it came to be named the ‘Peace Research Institute’ – that ‘conflict’ was not included in the name.

That is what it was called from 1966, when it became fully independent?

That is when it happened. Exactly. It was an important statement. In the Netherlands, a similar initiative was taken, but their one used an entirely incomprehensible name – The Polemological Institute. It means exactly the same thing, and sounds very nice, but reflects a wish to avoid the political concept of peace. The Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) is also a part of this story. NUPI became the foreign policy institute. PRIO and NUPI were … I don’t know if we should call them adopted siblings. Some supported one, others the other, and both have done well. But, being a peace researcher – that was to make a political statement.

Then there were these strong Nordic connections. They came to us, almost like refugees, university refugees, because of what Johan stood for, which was an inter-disciplinary approach.

It is significant that it came to be named the ‘Peace Research Institute’ – that ‘conflict’ was not included in the name. […] Being a peace researcher – that was to make a political statement.

Yes, I do know some of those who came to Oslo in the 1960s – including Raimo Väyrynen, Peter Wallensteen – and they speak about their Oslo experience as having been formative.

Non-Violent Resistance

In the aftermath of the Second World War, my father, Haakon Holmboe [1905–80], was very interested in international affairs, and obtained a UNESCO scholarship for travelling in the US and around Europe to investigate what they did in terms of international education. He was part of a group of history teachers who contributed to cleaning up German history books.

He was also a part of the first cultural delegation that visited the new People’s Republic of China in 1950 and wrote letters home. During the German occupation of Norway, he had played a role in the Teachers’ Resistance and been among those interned at Kirkenes.[8] I have written about all of this, in a little book distributed among members of my family.[9] But, regardless, these are threads that take us far back. In that way, things are interconnected.

The Second World War and your father’s engagement must have had quite an impact on your family and yourself?

Yes, you know, it did. Not the least for my mother. That is the way it was.

I have frequently brought international visitors to the Resistance Museum in Oslo, and although I don’t know a whole lot about it, it is my clear impression that the Teachers’ Resistance is rather meagerly represented in the history of Norwegian resistance overall.

It was a non-violent campaign, after all. My father was a member of the Resistance Museum’s first board. He had then become a grandfather (to my children), and I remember that he had small boxes put in place so children could climb up and look into the cabinets. You may be right that the Teachers’ Resistance has not been given all the attention it deserves, but what is even less known, for sure, is the Parents’ Campaign. Very little work has been done on that. It was not included by the leadership of the Resistance Museum, clearly because it was a campaign run by women. So, it is barely known at all that a quarter of a million Norwegian parents wrote protest letters against the Nazification of Norwegian schools.

They signed: ‘My child shall not!’ The male resistance leaders were so worried about this campaign, that some link in the chain might crack, because it was women who travelled around carrying those letters… So, there were in fact two separate organizations. There was the Teachers’ Union and the Female Teachers’ Union. And they had a foundation also in a network of priests. So, they travelled around and distributed information about what was going on. And they managed to keep it secret. Apparently, full laundry baskets with letters arrived at the ministry that were never counted. And now they are gone. This is a fantastic effort that is barely known.[10]

Very little work has been done on [the Parents’ Campaign]. It was not included by the leadership of the Resistance Museum, clearly because it was a campaign run by women. So, it is barely known at all that a quarter of a million Norwegian parents wrote protest letters against the Nazification of Norwegian schools.

What was the thinking behind the reluctance of the Resistance movement (Hjemmefronten) to recognize the Female Teachers’ Union?

From what I have understood, the Teachers’ Protest – which, at least when it came to arrests, concerned only male teachers – had contact with the leadership of the Resistance. They knew each other. My father was in Oslo and picked up directives (paroler, as they were called) in a matchbox. And he got cash that he would carry and distribute to those who needed it.

But the female teachers’ campaign didn’t have such help. They never got any authorization from the Resistance leaders. It was truly a non-violent campaign. You know, these were Women’s League people [i.e. Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, WILPF]. And they knew what they were doing. I knew Helga Stene [who played a key role in organizing the Female Teachers’ protests], or I got to know her, through the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), but I knew nothing then about what she had been engaged in. I have tried to read up on this, pick up things here and there. It seems that two generations had to pass before we could start talking seriously about the war. That I understand. Because I have it in me as well. And that which holds something personal in it, is not easy to put aside.

The Second World War and Early Peace Research

Can you say more about the impact of the Second World War on your engagement with peace research?

It has been there all the time. And in a way, it was amplified by the fact that I married Herman. Not so much because of his uncle Otto Ruge, who followed a long family tradition of engaging with the military. In the days of the Danish-Norwegian state, young Ruge boys were sent to Copenhagen at the age of ten or so to become military officers. For me, it was far more important that Herman was a pacifist. He objected to military service. He and I have basically followed each other throughout.

So, how important do you think the war experience was for shaping PRIO’s origins? Was it just there as an unspoken backdrop? Was it made explicit?

We did not make these things explicit. The wars that we studied were not the recent one we had experienced ourselves, but duels in the Middle Ages and the conflicts of the period after the Second World War.

So, you actually stayed away from the recent Norwegian war experience?

I don’t think this was a conscious decision. It was just…

If one had addressed it directly, would it have become difficult?

Yes, this was at a time in history – the end of the 1950s and beginning of the 1960s – when, for example, being the child of a Nazi collaborator was a really difficult theme to bring up.

Right. But the key decision-makers in Norwegian society had been formed by the war experience, by what they did during the war?

Absolutely, yes. I mean, they had all been involved, in one way or another, but drew different conclusions. This was politicized within the debate.

This had less to do with research than with politics. For those who opposed Norwegian membership in NATO, it was important to bring on board people who were known for having played a role in the Resistance. To bring them along. It was Karl Evang[11] who took the initiative to get that debate started in the 1950s. And, concerning Vilhelm Aubert,[12] a lot of people were unaware of his prominent role in the Resistance. I did not know until I attended his funeral and discovered that he was given full military honours. Well, he had been a key member of XU [the Norwegian Resistance intelligence unit].

It was strange seeing that. Here you sat with those who had had him as a teacher, those who held him as a friend. I was surprised. But it was also a cultural thing. For me, when I attended the funeral of Herman’s uncle, Otto Ruge, there were so many people there, I wondered if they would be able to get in at all. The parliament and everybody else were there. Wow! Is that what it was like? I had met him at Christmas family parties, and I knew who he was, but not how central he was.

So, I have basically lived my life in an environment where the war experience was important, but without really lifting it up to examine it. I think that is the right way to describe it. For me, it has been important to engage in things related to international peace.

Peace Activism

Ingrid and I were both recruited into the WILPF in the mid-1950s. At that time, we were both students. And this was just after a plane crash had occurred, an accident that killed virtually the entire leadership of the Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights.[13]

They were on a delegation trip to the Soviet Union. The plane crashed. That included the leader of the Women’s League and many others in the Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights. They lost their entire leadership. The Women’s League wanted to bring in younger members – Ingrid’s mother was part of that milieu – so we did not have to do the dishes, we were taken straight into the national board. And, in a way, we got right into international work on a fast track.

So, this means that you were both peace activists before you became peace researchers?

Yes, absolutely. That went hand in hand. Herman, after all, was one of the students who distanced himself from the pro-NATO camp and attended these East European student festivals. He went to Bucharest, and we went together to a student festival in Warsaw in 1953. And at that time, a resolution was adopted in the Students’ Association (Studentersamfunnet) that this was something Norwegian students should not do.

A resolution promoted by whom?

Well, they controlled the student organizations. It became known later that the student associations were supported by the CIA. It was a tiny little university environment, where we knew each other. Our parents had also known each other as students, and so on.

And the Students’ Association was an important meeting place at the time?

Yes, very important! We attended Saturday meetings at the Students’ Association for many years. That was what we did. We did of course also drink beer, but that was where the debates unfolded. And they could be rather heated. It was the main platform for the open exchange of views.

Non-Violence as Pragmatism

Now, talking about the war, or rather about what the war meant for the research environment: a few years back, I had a long conversation with Gene Sharp, the author of so many key texts on non-violent activism. This was when he visited Norway to receive the Prisoner’s Testament Prize from Travel for Peace (Aktive fredsreiser). I was privileged to have him with me in my car all the way down to Risør. That was very interesting, we had a long conversation.

That must have been interesting. Absolutely.

And he, amongst other things, was preoccupied with your father.

Yes, he had heard about the Teachers’ Resistance and wanted to interview… he came here because he wanted to meet Johan and learn about what he stood for. Sharp was among several PRIO student visitors who rented a room in our house, where I still live.[14] Through this, he got to know about my father.

Gene was extremely keen to talk about his conversations with your father. At the time, I had no idea that I would be talking to you today, so I was not the one drawing attention to your father’s role.

He saw this as a non-violent campaign. And, in that way, not as part of the Norwegian Resistance Movement, which included a military wing (Milorg).

In our conversation, he went as far as saying that much of what he had been working on later in life was inspired by what he had learnt in Norway, about non-violent protests in the course of the war.

Yes, I can imagine he did. Non-violence was, as my father said, the main weapon we possessed. But for him it was not a moral principle. He said it was what it became, and that it worked. But my father also conducted exercises with Sten guns with his high school pupils.

Non-violence was, as my father said, the main weapon we possessed. But for him it was not a moral principle. He said it was what it became, and that it worked. But my father also conducted exercises with Sten guns with his high school pupils […] what he called ‘German lessons’

Jacob Jervell[15] has since told stories… And Jacob, whom I came to know quite well, had my father as his teacher for five years. He was inspired by him, they were both the sons of priests. But Jacob has an account of what he called ‘German lessons’ [i.e. gun practice].

So, my father was not a pacifist. He also went to the Trysil mountains and received airdrops. And it was after one of these trips that he got arrested. That was quite some time later than the teachers’ protests. He did not want to talk about this later, but that was what happened.

So, his use of non-violent tactics was a pragmatic choice?

Yes, it was. It was what he saw as possible. I believe he writes that, during the transportation of the arrested teachers by ship to the north, there were two who resisted – I am not sure how, but on a principled pacifist basis – and they were locked into a room of their own so that they would not influence others.

The women-led Parents’ Campaign was of course entirely without weapons. Ingrid and I met Gene Sharp again when he attended the Films from the South festival. His interest in the non-violent aspects of the Norwegian Resistance probably gave us a new understanding of it as well. Yet, strangely, the work of Gene Sharp and that of Johan – who had also collaborated with Arne Næss[16] on Gandhi – did not become connected. Johan’s work on non-violence was very theoretical – I’m referring to the work on Gandhi’s political ethics.

You are referring to Johan Galtung’s project with Arne Næss becoming overly theoretical? Is that what you are thinking?

Yes, it had to be. But then, Arne Næss had also been active in XU during the war. So, I’m wondering what role the war actually played. I believe that it is only now that we can see the contours of that more clearly. Many of those who I met in the Women’s League, who were then adult women, were active during the war, but also before the war. They were politically active, they understood where things were heading. So, they had been anti-Nazis for a long time.

I think that generation – particularly those who had spent time at Grini [a detention camp close to Oslo, run by the occupation forces from June 1941 to May 1945] – wanted to leave the experience behind. They probably hoped that it would kind of fade. Herman’s sister, who is five years older than him, spent 15 months at Grini in her early twenties. She was arrested for distributing illegal newspapers. She said that it took many, many years before she could bear to talk to her children about it. It was only towards the end of her life that she found the energy to write some of it down.

Pensioner and Activism

So, by now, I have actually been a pensioner for 20 years. But overall, you may say that my whole professional life has revolved around the connection between research, politics and society. I don’t know it if has left many traces, but I, at the very least, have had quite a variegated experience, and I think my professional life has been interesting.

Mari Holmboe Ruge being interviewed about WILPF in 2015. Photo: Sissel Henriksen, with kind permission

For sure it has. It must have been extremely interesting to relate to research as a political factor from so many different vantage points. In the governance structure, within research policy advice, and as a researcher.

But I have not always been sufficiently good at maintaining a sustained focus over time to stay committed to more comprehensive research engagements. And, there is something else: I grew up in a family of teachers, but I never enjoyed teaching. I look at the youth sitting there, and then I think: ‘My god, what do I know that I can tell you?’ No, I have instead thrived in offices – with a screen, a phone – and with writing stuff.

A lot of what I have spent time doing after I retired, before health issues became more prevalent, was working full time for the Women’s League. It never had the resources to pay anybody. And I thought it made sense. It worked well for me. I had this as my main engagement for at least a ten-year period.

The Women’s League! Its focus has been on peace, more than on women’s rights, has it not?

Yes, and that is also interesting in its own way. That there is an association, an organization of women, but not primarily for women’s issues. I find that it becomes more and more interesting when I ponder how the founders were thinking. These were women with a background in the Women’s liberation movement. They organized the fight for voting rights, but in 1915, when the First World War raged, they realized that without peace the right to vote would have little value. So, the first conference stated very clearly that although it was intended to be a conference on voting rights, due to the war it changed into a conference on peace, and they managed to pull this off even though it was 1915. And it is said in that statement that all participants had to declare their support for women’s right to vote. In a number of countries, the women who had been fighting for voting rights put that struggle aside, and worked for peace. Then later they picked up the struggle for the voting rights again.

Five years ago, we had our centennial, and I wrote a bit about this. When reading up on the subject, I realized that these women actively – and I believe very early on – took issue with the conception of war as a kind of heroic affair. So, after the horrors of the trench war became widely known, many saw that they were right, but they had written about this already in 1915.

Today, the League is an explicitly feminist organization, otherwise we could probably not have survived, but it was always an association for women. They wanted to present a mirror image of conventional diplomacy to demonstrate that women had the ability to organize and to contribute to decision-making.

This small organization had elaborate rules for conducting its activities, in contrast to most women’s organizations. I didn’t appreciate such formalities until many years later, but the women that I met were pioneers and had practised them since the very beginning, in order to be taken seriously by the male community. They mastered this fully. It was bothersome, but the formalities sustained the organization.

This was the first generation of women who had access to higher education. But then, they could not get a job! Or, they could get a job, but not a career that corresponded to their qualifications. So, what these women have done – and I have looked rather carefully at the Norwegian ones – is to use their competence, their language, their money, to build, to travel, to construct an organization.

And many of them never married. So, they didn’t have to ask anyone for permission to do what they did, right? For this reason, only some of them have children and daughters succeeding them, while most do not. But they were doctors, lawyers, businesswomen. They hail from a range of political parties. So that was also very clear, all the way up until I would say 1946, ‘47, ’48: to work for peace, that was something all decent people did.

We have had Conservative Party women, and many Christians, in the Women’s League. They have felt at home there. The exception is the Labour Party – their women had their own organization.

In all these years that you have been engaged with the Women’s League, what have been the most important questions for you?

We very much need organizations for connecting things. I have been out in marches and demonstrations and that sort of thing, but to me, it was always the broader, organized interaction that was most important. It might not be the sexiest of things, but not much would get done without it.

For me it is, if you ask for political issues, then it is related to organizing. Far more that than any singular issue. There are of course many important issues, but no single issue has been at the centre of my attention. So, my answer here is rather generic: there are certain environments where I feel at home. I like to be in the head office of a well-functioning organization.

And it should have a value-based international orientation. We very much need organizations for connecting things. I have been out in marches and demonstrations and that sort of thing, but to me, it was always the broader, organized interaction that was most important. It might not be the sexiest of things, but not much would get done without it.

Thank you very much, Mari.