Hilde Henriksen Waage, researcher and historian specializing in the Middle East, at her University of Oslo office with a textbook she co-edited for Professor Helge Pharo’s 70th birthday in 2013, June 2019. Photo: © Mimsy Møller / NTB Scanpix

Hilde Henriksen Waage, interviewed by Henrik Syse

Between Israel and the Palestinians there has always been a huge asymmetry of power. There is a strong party and a weak party, and this has made it impossible to achieve a genuine peace. A nice little bridge-builder like Norway cannot easily change the policies of the stronger party, particularly when this party is backed by an even stronger one, the United States. I say this not because I am pro-Palestinian or an Israel-hater. My point has nothing to do with love or hate. I say this as an academic researcher.

Henrik Syse: Ok, Hilde, I know this is what you have been saying all along. One of your research projects was even called ‘The Missing Peace’. Let me still ask about your expectations for the future. In 2039 you will be 80 – and I will follow in 2046. Maybe this is a banal opening question, but will the Middle East be more peaceful then?

Hilde Henriksen Waage: I do not believe so. I am basically a positive and optimistic person, but when it comes to the conflicts in the Middle East – and there are many of them – I am afraid we will not be any closer to a peaceful resolution. Research into history has rather shown us that things have gotten much worse.

Is that a conclusion you draw on the basis of your study of history? Or is it more a conclusion based on what you see as of 2019?

Both. The one should not exclude the other. As a historian, I often ask myself: what if anyone had asked me to be a negotiator or mediator in the Oslo Process? Based on the premises of that process, what would I have answered? I would have said: ‘No. I cannot do that based on those premises, because I have no belief in it succeeding, based on the knowledge that I have.’

We will certainly come back to that. This is indeed an exciting aspect of interviewing you: you have a rich PRIO history, and at the same time you have done research on one of the most famous and important conflicts there is, not only in the Middle East itself and in many parts of the world, but more specifically here in Norway. You have written about a subject that fellow academics and specialists find interesting, but that has also been a key part of Norwegian politics and society, and that has made many people really angry. Let’s start with you, though. If you were now being interviewed by someone who knew nothing about you, what would you say about your background from before PRIO?

Born into the Salvation Army

I was born in Drammen. ‘Harrybyen’ Drammen, as some say – you know, ‘the redneck city’, as I guess one would say in the US. That is how many people saw it then. I was born into a middle-class, bourgeois, Christian home, where my parents believed in what the Bible said, and they believed in the State of Israel. In other words, I grew up in a pro-Israeli home. So, you might say that these issues were with me from day one, this interest in and the strong viewpoints on the Middle East.

In the 1970s, my friends – or rather, the friends of my parents – had joined what is today the Socialist Left party (SV) and what we now call the Palestine Committee (Palestinakomiteen). And in the early 70s, in the social environment that I was part of, that was really unusual. These friends were my parents’ best and closest friends, but they had a political standpoint that was pretty far removed from that of my parents. My parents were people of faith. Both were active soldiers in the Salvation Army, which I was certainly part of, too. My dad taught at Danvik Folk High School (Danvik Folkehøgskole) in Drammen, which was owned by the Inner Mission (Indremisjonen), the more conservative part of the Norwegian Christian Mission movement.

And I remember from when I was a little girl that my sister and I were dismissed from the table when my parents and two of their very close friends, Ingrid and William, were discussing Israel. I wondered what could be so wrong about this country of Israel that it made my parents and those I considered my aunt and uncle so angry that they simply could not behave in anything resembling a normal way.

But at the same time, your parents were progressives in their way. Your father was what we in Norwegian call a ‘husstellærer’, or someone who taught home economics and domestic care, right?

My father was a composite character politically speaking. He had a great influence on me. I believe that for him – and there were differences between my father and mother – the support for the State of Israel, as for many of his generation, was very much premised on the persecution of Jews during the Second World War, as well as his basic socialist beliefs. But this was socialism within the framework of the Christian People’s Party (Kristelig Folkeparti); that is what we are talking about: a form of Christian Socialism. So, for him there were many important reasons to support Israel.

My father was educated as a teacher, and at Danvik Folk High School he taught English. When I was five years old, he brought our whole family to England to study for a year at the University of Newcastle. And so, I started school in England at the age of five, and I thought it was terrible. I did not understand a thing they were saying, and in Newcastle it was ice cold – that is what I remember best. And this was a pretty radical thing to do at the time. Mum had to work in a school for girls who had committed criminal acts but were too young to be imprisoned. Dad had to live with an English family in order to learn English.

And so, he taught English. He was also very preoccupied with philosophy, so I grew up with Socrates and Plato, and Dad sat through all our vacations reading philosophy books. And he was deeply engaged in the push for equal rights for both sexes. He was, I believe, the first man – along with 120 women – to attend the Teaching College for Home Economics and Domestic Care (Statens lærerskole i husstell) in Stabekk [west of Oslo]. There, he took a one-year course in home economics in order to become a teacher, and to provide a male example in this role when it comes to equality between the sexes. That is what I grew up with.

Now, just for the record, and to get the historical facts straight, tell me their full names and dates.

Indeed. Dad was Johan Henriksen, originally from Fredrikstad, son of a Finnish father who had fled Finland because he did not want to serve in the military. This must have been before the Russian Revolution and the Finnish Civil War, and I would think that this would have warranted the death penalty. So, instead he became a ship captain and sailed the seven seas – and ended up in Fredrikstad in Norway. My mother, Ragnhild, whose maiden name was Myhrvold, came from Drammen. She hailed from a poor working-class family, with a father who was an artistic painter and a stay-at-home mother. My mother obviously had talents because she had received stipends from several sources so that she could complete high school, which was quite unusual for girls of her class background at the time. She had academic talents and ended up as a schoolteacher, exactly as she had wanted. As for the dates, Dad was born in 1929 and Mum in 1931. And it was my mother’s side that were active in the Salvation Army.

The Salvation Army is in a way my second home, my spiritual home. There, I’ve attended everything from Sunday School every Sunday to Sunday services at 11 – holy meetings, as they were called. I have been through all the ranks in the Girl Scouts, and sung in their Ten Sing choir, even singing solos before I managed to destroy my voice. In short, this was my home, and it was also at the first co-ed Scouts Camp of the Salvation Army in 1975 that I met my husband.

This is a good background for you to have, since it gives you direct knowledge of a part of Norwegian society – the Christian community – who have been extremely interested in your work, not least on Israel. At times, when you have been maligned or attacked, I am sure you must have thought, ‘how can they say such things?’ It might then be good to know a bit more about this environment from the inside, and to know that it is also a place for warm and engaged human beings.

When I started studying Israel in the 1980s, I did not come into it from a radical, pro-Palestinian youth background. I came into it from completely the opposite side. But then I realized that there was something about the relationship between the map and reality that did not quite fit.

Yes, indeed. To this day, I feel great affection and warmth towards the Salvation Army. I mean, I could nominate them for a Peace Prize. There is something about their understanding of Christianity, and their social work, which I have appreciated from when I was very young all the way until now. I just need to hear a brass band and it makes me happy. Although I am not now active in the Salvation Army at all, it is and remains my spiritual home. And this is what many do not know about me: namely, that when I started studying Israel in the 1980s, I did not come into it from a radical, pro-Palestinian youth background. I came into it from completely the opposite side. But then I realized that there was something about the relationship between the map and reality that did not quite fit.

Drawing of Hilde by Dagbladet’s legendary cartoonist Finn Graff, 2004.

How long did your parents live?

Dad did not reach a very old age. He died in 1998 at the age of 69. He had been seriously ill for many years. My mum died in 2015, at 84.

And your sister, how much younger than you is she?

My sister Ragne is two years younger than me, born in 1961 – and a teacher, like the whole family, really.

Becoming a Historian

And that leads us to the start of your studies. When did you decide that you wanted to delve in the manifold problems of the Middle East?

Well, at the time I was living in Trondheim, because my husband Geir [Morten Waage] attended what was then called NTH (Norges Tekniske Høyskole), and today is called NTNU (the Norwegian University of Science and Technology; Norges Teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet). He was studying to become an engineer.

And you married in …

Ahh, that’s 100 years ago now. In 1980. At that time, I had already studied for three years at the Teachers’ College in Halden, and then I moved over to history to take what was then called grunnfag and mellomfag in history [equivalent to a Bachelor’s degree with a major in history] in Trondheim. I was about to start my Master’s degree (hovedfag) and was wondering what to write about. In Trondheim, there was a totally different environment for history than in Oslo. The emphasis there was on the history of the labour movement, women’s history, and so on. And I soon realized that those fields were not really my main interest.

Already at the Teachers’ College I had become interested in international politics and Norwegian foreign policy, even if that was not much discussed in our home, with the exception of the Middle East and my dad’s political interests. And as we were winding up in Trondheim, planning to move back to Oslo, I called the professor at the University of Oslo who advised students on such topics. That was Helge Pharo. All I knew about him was that he was an 800-metre track runner. I had even seen him running around at the University. And I had found out that he was advising students who were writing on topics related to foreign policy. So, I called him up and told him my name politely, and I wondered if he could help me come up with some topics. And he said: ‘Well, I think you should write a thesis about European integration.’ And I went: ‘Ugh! [Æsj!]’ And he replied: ‘Excuse me? What are you saying?’ ‘Well, I didn’t mean to say “ugh!”, but don’t you have anything else?’ I just thought it sounded so boring. ‘OK, what about the conflict between Greece and Turkey since 1945?’ And I said: ‘Well, that’s a bit more interesting, but you haven’t quite hit the target.’ So, I simply said I would think about it, and then I started reflecting on all those loud discussions about Israel that I had grown up with. And I thought, why not just study the one thing I have always wondered about: what is so wrong with that country, since it makes everyone so angry?

A few days later, I called Helge Pharo back and asked: ‘What about Norway’s relationship to the foundation of the State of Israel? Could I write about that?’ And he replied: ‘Is there anything to write about on that?’ He has since said that that was an incredibly stupid thing to ask, not least in light of what I actually found. Well, that is how it began. And I think the reason why I chose to write about the Middle East was exactly that background of experiencing all those discussions about Israel.

This must be around 1983? Or 84?

This is 1983.

May I just mention a funny anecdote? I finished high school in 1984, and I chose to write for my written exam in Norwegian about the conflict in the Middle East. I knew that could be a topic that came up, so I had really prepared. And my big hero was Shimon Peres. And the 18-year-old Henrik wrote about how Peres broke with Menachem Begin’s line. Well, I always say that if they had read my exam from 1984, they would have had peace now! But of course, no one but the examiner ever read it. I came from a home where support for Israel was seen as part of the support for western ideals and not least part of our obligation since the war.

But I remember how my father, an active politician, always stressed to me the importance of respecting belonging and culture, and that was in many ways what got me to think more deeply about the plight of the Palestinians. But enough of that – how did the history of Israel lead you to PRIO?

Well, it’s 1983 and I’ve had this conversation with Helge Pharo, and we have spoken several more times about how to proceed, and we agree that I should apply for access to the archives of the Norwegian Foreign Ministry. That was, of course, Helge’s idea, and I was very enthusiastic. And he assumed that it would be easy to gain access to those papers – nothing controversial there. Everyone knows that Norway at the time was a strong and warm supporter of Israel. At the same time, PRIO announced a possibility to apply for student stipends. Well, all I knew about PRIO was the noise generated by Nils Petter Gleditsch and his book on NATO listening stations in Norway.

Oh, I remember that, too.

Arriving at ‘Hippie’ PRIO

I remember it very well! I had an image in my head of Nils Petter in this court case, and all the publicity around it. But I had no strong preconceptions about PRIO, except that I thought it was probably a bit of a rabid, ‘hippie’ place, to put it that way. I thought that it was not quite in the mainstream, but I did not really know much about the place. Anyway, I thought this must be a good idea, so I actually spent two months writing my application and I flew from Trondheim to Oslo to go to an information meeting for students in late 1983.

There were lots of students there, maybe 30 in total. Asbjørn Eide, the father of Espen Barth Eide [who later became both Defence Minister and Foreign Minister of Norway], chaired the meeting. I brought this application that I had worked so hard on – a project outline of about seven pages. I remember there was this other girl who was working on domestic violence, and Asbjørn Eide told us both after the meeting that we could just go home – our topics were not ones that PRIO would be interested in.

And I was so disappointed – I had travelled all that way and everything. So I went out into the corridor, and I saw someone I did not immediately recognize. I soon realized it was Nils Petter Gleditsch, who had been listening in from the outside through an open door. And he said: ‘Hey you, don’t go. I am interested in your topic. Tell me more about what you want to write about for your thesis.’ I knew that Nils Petter had already advised several history students. Well, I told him about my plans, and he said that I should write an application. ‘I already have an application,’ I told him – you know, ever the good girl, having done my job and all. ‘Well, give it to me, then,’ he said. ‘You’ll hear back from me.’

Well, I went back to Trondheim and I heard nothing. And in January 1984 we moved to Oslo, and someone called me and said I had received a whole year’s student stipend at PRIO. There had been 70 applicants in all, and two were successful. One of them was me, and the other – I later heard – was Jan Egeland. And that is how I came to PRIO. It really feels quite arbitrary.

Well, not really that arbitrary. It seems to me that Nils Petter, listening to you, understood that your project outline was truly good. You had already then decided that your topic would be the founding of Israel and Norway’s relationship to that event, right?

Yes, yes.

But you still had no clear impression that there was something there that gainsaid the official story?

Quite right – I had no such impression at all. I had formulated this as my topic, and I had – during the fall of 1983 – sent applications for access to the relevant archives of the Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet), the Labour Party’s parliamentary group, maybe also the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO), and that’s all I remember. And I had not received any replies yet. So, I was just waiting, while I had started reading relevant literature.

OK, let us just take the formalities. You got a stipend and could work from PRIO. Who was your supervisor?

At the University of Oslo, where I was part of the programme in history, it was Helge Pharo. And at PRIO it was Nils Petter Gleditsch. It was the two of them.

Right. And they worked well together?

Oh yes. In my opinion, and I know they don’t quite agree with me, but I truly feel that I would never have completed that degree or become a historian if it hadn’t been for the enormous support and backing and excellent advice they gave me. They did so from two different places, not together, but it worked very well. And then I remember, in February, that Nils Petter told me that he had found money for me so I could go to the US to delve into archival files there, too. And I had to tell him: ‘But, Nils Petter, I can’t do that – I’m expecting a child.’ And I thought it was terrible. But he just said: ‘Oh, how lovely.’ And I replied: ‘Do you really think so?’ Because that wasn’t really my plan then. So, there was no trip to the US at that point. But I had a child and I continued writing my thesis at PRIO.

Nils Petter [Gleditsch] told me that he had found money for me so I could go to the US to delve into archival files there, too. And I had to tell him: ‘But, Nils Petter, I can’t do that – I’m expecting a child.’ And I thought it was terrible. But he just said: ‘Oh, how lovely.’

And so Kristoffer was born, right?

Yes, in September 1984.

Hilde pregnant with Henriette, with son Kristoffer (left), her daughter Katrine (right). Photo: private archives

And when did you pick up the writing again?

Oh, there wasn’t much of a break.

Typical you, eh?

Well, I am not very good at being pregnant either. There was work more or less all the time. I collected sources and brought the literature with me constantly, and I had this new typewriter with a correction key.

Oh yes, I remember that one – the correction key! Fantastic!

Oh yes, fabulous. This was before personal computers, right? And I remember my husband Geir said, ‘The only place you do not work is when we are out on the boat; otherwise you are carrying this stuff around all the time’. And I did. With the baby and everything. Writing and writing.

And when did you submit your thesis?

That took some time – I submitted in May 1987.

And you were at PRIO all the time, except when you were at home due to maternity leave. Did you have any income?

Oh, things were really tight. And do not imagine that we had a huge civil engineer’s income from Geir at that time, because we did not. But I did have the student stipend from PRIO, and then – which partly explains why things took so long – I got a stipend from the Research Council of Norway that was given to one female history student and to one female philosophy student, in order to encourage recruitment of female researchers within those male-dominated fields. And that was quite a big stipend, several thousand kroner a month for a full year. That was good, because I realized that I had a much more daunting task ahead of me than I had initially realized. And I had the baby and everything. But anyway, it all ensured that I had time to write quite a comprehensive thesis and still have money for food.

The First Controversial Findings

Tell us more about the process – because this thesis would become quite controversial.

To be honest, I was a bit gullible and naïve about what it would be like to deal with politically controversial questions. I do believe, as I did then, that it is possible to be a proper historian, a good historian, and to be judged academically on the basis of one’s work. Unfortunately, however, that has not been my experience – that’s not the way it is when you reach conclusions that contradict widespread opinions.

And what were those conclusions?

I was a bit gullible and naïve about what it would be like to deal with politically controversial questions. I do believe, as I did then, that it is possible […] to be judged academically on the basis of one’s work. Unfortunately, however, that has not been my experience – that’s not the way it is when you reach conclusions that contradict widespread opinions.

Well, my conclusion was the following: Norway had not at all supported the creation of the State of Israel from the beginning. Norway had first wanted to send the Jews who had survived Hitler’s extermination attempt to somewhere in South America. That was official Norwegian policy, and the Labour Party first got angry with me saying that, because they did not want to admit that they had supported a Jewish colonization of South America. They hoped that could be passed over in silence.

And these were not just minor figures within the Labour Party?

No, no, this was the [Einar] Gerhardsen government’s stand, and it was held by the two leading figures of the Labour Party at the time: Haakon Lie, the party’s general secretary, and Aase Lionæs, who for many years chaired the Nobel Committee. Aase Lionæs was very angry with me. And I was so surprised, because I had only seen her on TV. And I could not understand why they were so angry at what I had found in the Foreign Ministry’s and Labour Party’s own archives. I will say about Haakon Lie, though – and much can be said about him – but when I interviewed him about this he said: ‘Can you imagine, Hilde, that I could have stood for something so stupid back then? But that’s what I thought at the time, so I just have to stand by the mistaken opinions I had.’

My conclusion was the following: Norway had not at all supported the creation of the State of Israel from the beginning. [… ] And I could not understand why they were so angry at what I had found in the Foreign Ministry’s and Labour Party’s own archives.

The greatest problem came with the Foreign Ministry. And I was not prepared for that, since I had received so-called privileged access to still classified documents. That meant I had access, but that the ministry reserved the right to read my manuscript after I had done my research, before publication. And that’s what created the problem, because when I handed them my finished thesis for what’s called ‘release’ from the ministry, I got into trouble with some of those bureaucrats and friends and colleagues of the actors I had written about.

What I had found out, in brief, was that four top Foreign Ministry bureaucrats had gone behind the back of the Gerhardsen government, which had decided to support Israeli membership of the UN: first, in the Security Council, where Norway had a seat, and then in the General Assembly. They simply sent a telegram of their own where they added their own sentence – and I found this in the source materials as a handwritten addition – saying that Norway was not to support any Israeli UN membership, but should instead abstain from voting in both the Security Council and in the General Assembly.

Did they have any support elsewhere in the West for this – what about the UK, for instance?

The UK was a bit of a special case, because they had been the Mandate Power in Palestine and had keenly felt the problems associated with creating a Jewish state there. So, they were against.

Hence, these Norwegian bureaucrats were not all alone.

Right. What they primarily referred to was international law, since most of them were lawyers and experts in international law. They did not want to formally recognize a state whose borders were not clear, which was at war with its neighbours, and which had created a huge Palestinian refugee problem. They did not want such a state to become a member of the United Nations, at least not at that point. What created the huge commotion was of course the fact that these were now unfaithful servants vis-à-vis the Norwegian government, even had they not succeeded. And in 1987, that became too much to handle for the Foreign Ministry: that I had found and could document that leading Foreign Ministry officials had gone behind the back of the government.

So, what was the process, then, to get this declassified and published?

The deal was that I could publish the findings, but that the sources should remain classified. I was called into a crisis meeting at the ministry, two days before Christmas Eve, I remember. I had the sense to bring Helge Pharo. I did not know at this point what I was going to be asked. All I had got – signalling that this was serious – was a phone call to my parents, with whom I was living temporarily. The ministry said that I had to come and give them some answers, but I didn’t know what the questions would be. In that phone conversation, they explained that the contents of the conversation remain classified until you get there in person. And when I came for the meeting, the whole leadership of the ministry was there.

Those are the bureaucrats, right? Not the political leadership.

That is right. The Foreign Minister, Thorvald Stoltenberg, knew nothing about this. They called the thesis ‘indecent and slanderous’. They demanded that I re-write the thesis in forty different places in order for me to have it declassified and published. And I fought back. Not because I’m tough or anything, but because the agreement I had signed with the ministry stated that the ministry could demand information be withdrawn if it pertained to state security or purely private information. But there was nothing like that in the materials of my research. It was just that they did not like its conclusions. So, when I replied that I refused, the ministry people were really shocked that this young lady would not give in to their demands to have the ministry portrayed in a better light. I simply refused.

They called the thesis ‘indecent and slanderous’. They demanded that I re-write the thesis in forty different places in order for me to have it declassified and published. And I fought back.

This must have been quite a tough process – and I assume it was not solved overnight. Probably Christmas and the New Year passed. You said it was good you brought Helge Pharo. What was Helge’s reaction?

His reaction was sharply critical, just like mine. We both tried to find out what this was all about before we went into the meeting, and we each tried to figure out how to react and what to say. I remember we met a relatively young man out in the corridor before the meeting, a Principal Officer (byråsjef) called Knut Vollebæk [later to become a Foreign Minister representing KrF (The Christian People’s Party)]. And we had no idea what the meeting would bring up, right? And he pulled me aside and said something like: ‘This meeting will be pretty terrible for you. But try to keep calm, and I will help you solve this afterwards.’ If I had not received that warning ahead of time, I don’t know how things would have gone.

I mean, both I and all the Foreign Ministry people were so angry. The lawyer they had called in to evaluate whether they could sue me for libel actually said that the ministry probably didn’t have a very strong case. But in a way, that didn’t help. Helge Pharo defended me, and that was good. He defended me and also history as an academic field, both during the meeting and afterwards, and I remember he said something like: ‘This is a really good thesis: it is academically strong, she has treated the source materials professionally, and I cannot see that she has been slanderous in any way, or has pressed the sources too far – I actually think she could have gone much further.’

Well, after several rounds – this must have taken something like nine months altogether – the Foreign Ministry finally gave in and cleared the thesis. The Foreign Minister, Thorvald Stoltenberg, had also gotten wind of the story, and I have been told that he said to the ministry’s people: ‘Get this matter out of the way now, please. Can’t you see that you are doing more harm than good?’

I guess this says something about the respect people like Thorvald Stoltenberg and Knut Vollebæk had for academia, after all – and the way in which they understood the fact that people have different roles. But what about PRIO? How did PRIO relate to all of this? Who was PRIO’s director then?

Sverre Lodgaard – and Sverre was a personal friend, from what I remember, of several who had been in that meeting at the Foreign Ministry. They had spoken to him several times, both before and after the meeting. Beforehand, he had assured them that I was a nice person who would undoubtedly listen to their advice. After the meeting, I have been told, they called Sverre and said: ‘You said this young woman was nice? Well, she is not – she’s tough as nails and won’t give in to anything.’

So, it was not primarily PRIO that played an active role here, but more Helge Pharo on behalf of the field of history, but of course with full academic, moral, and personal support from Nils Petter Gleditsch, who was also very concerned about the problem of secrecy. He had encountered this kind of situation personally just a few years earlier. Well, Helge Pharo really fought for this, also in his role as Department Chair for the History Department at the University of Oslo. And I think you are right about another thing: I think I was greatly helped by the fact that people like Thorvald Stoltenberg and Knut Vollebæk saw that one has to understand the role of the academic – and the Foreign Ministry bureaucracy just didn’t do that.

And then the thesis was released from the ministry and given to a commission at the University of Oslo, I presume.

No, not quite. The three people in the commission had already been permitted to read it, that was part of the contract. So, I had already passed my exam, with a very good grade, even, and to make matters even more difficult for the ministry, I had received a doctoral stipend, while they were still quarrelling and holding the thesis back. They essentially claimed that I did not understand a thing, while the academics came in from the side and gave me solid credit.

What happened to the thesis – it became a book right?

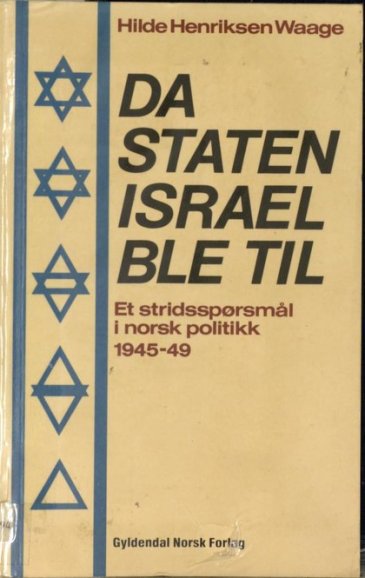

Hilde’s MA thesis (hovedoppgave) was published as a book in 1989.

Yes, by the time we were well into 1988 and the thesis had been released from the ministry, I wrote letters to more or less every publisher I could think of. I think I sent around 12 letters, saying: ‘Hi, I’m Hilde, and I have this thesis. Would you like to publish it as a book?’ I had no expectation that I would hear anything back – maybe Pax would reply, a socialist publishing house, but that would be it, I thought. And then I got one positive reply after another. I chose Gyldendal, and I was really proud when my thesis appeared as a book with them, under the title of Da staten Israel ble til (When the State of Israel was Born). I remember doing one of my very first media appearances shortly afterwards, about this book that had stirred up so much trouble. I recall one of the Foreign Ministry’s top bureaucrats went on NRK’s (the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation) news show Ukeslutt and said, ‘This is the book that we say is worse than Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses.’ Well, that’s how it ended!

One of the Foreign Ministry’s top bureaucrats went on NRK’s Ukeslutt and said, ‘This is the book that we say is worse than Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses.’

And the book came out in 1989?

Yes, right, 1989.

From Israel 1949 to Suez 1956

Tell us about the doctoral stipend.

Well, that was Helge Pharo again. He pulled the strings for me. I was going to finish my master’s so I could become a high school teacher, right? It is April 1987, and I’m completing my thesis and he springs it on me: ‘Hilde, shouldn’t you apply for a doctoral scholarship?’ ‘No, no, are you crazy?’ I remember replying. But he protested and said I wouldn’t get a scholarship right away anyway. I would have to apply several times. ‘Try now, and then you come back again next year, and then maybe … It’ll take you just two weeks to write the application, and I’ll tell you if it’s too bad to even send in.’ So said Helge. And I abided by what he said. I created a project about Norway’s relationship to Israel and the Suez Crisis in the 1950s, sent it in, and pretty much forgot about the whole thing. And then, in October 1987, they called me from the Research Council of Norway and told me, congratulations, you have a doctoral stipend!

Wow! And by that time, you had received your fine grade for your master’s, right?

Yep. And this was before the whole trouble with the ministry, which started around Christmas. In 1987, I actually had a rather long leave of absence because of an eye operation, but I was back at PRIO in 1988 getting ready to start my doctoral work, and then in 1989 I was pregnant again, with child number two, who arrived in September. That is Katrine. And I stayed home with her until April of 1990.

And let us take child number three right away, too.

Interrupted by PRIO Directorship

No, no, we will take another break from my academic work that I had first. I am a historian, you know. We have to get the chronology straight! Well, there I am, working away on my doctorate with two kids until we get to around May 1992, which is when Sverre Lodgaard calls me to his office, the Wednesday before Ascension Day (Kristi Himmelfartsdag).

The second floor of Fuglehauggata 11, right?

Yes, and I’ll never forget. I was really wondering what he wanted to talk with me about, because he was so insistent. And I’m way into my doctoral work, and I’m busy with the kids and everything. And then Sverre tells me that he has got a new job in Geneva and has to leave PRIO a year before his director’s tenure runs out. And he says: ‘I want you to be named deputy director and take over as director when I leave PRIO in August.’ I was pretty shocked, really shaken. Was he joking? I mean, I was so young, and there were so many other more senior researchers whom he could have asked, and he asks little me. That’s how I felt. But I did say yes.

And why? Because you liked the challenge? Because you liked PRIO? Maybe because you have a crazy streak?

Hah-hah – all of the above! Well, except I do not really have a crazy streak. I am pretty rational, to tell the truth. But there are two things that have always characterized my work life. First, it is my genuine joy and interest in doing historical research. And second, I love working with people, and I love to manage and lead others, to get things done together with others – that is something I have always enjoyed. So even though I had zero leadership experience, except for girl-scouting and a bit in Sunday School and things like that, and I guess some leadership experience from back when I studied to be a teacher, I did not really have proper leadership experience. But I always had the interest in directing and making decisions. And according to Sverre, those were abilities that he had detected. And so, I thought, well, how old was I? 32? 33? Well, I turned 33 that year in August.

Hilde and Geir (right) before a map of Palestine in 2014. Photo: Private archives

You were indeed young to be PRIO’s director.

Yes, at first I decided that it was unthinkable. But then I realized what an amazing opportunity it was. And so, I went for it – I mean it was only for a year anyway. But the Research Council got really mad: another leave of absence? You know, an eye operation, and then another child, and now you are going to be the director of PRIO?

I guess another trait that made you do it is that you are very conscientious. You want to do your duty.

Yes, I guess so.

And so, you think that someone must do the job anyway, and now I am being asked, and I’d better do it.

Yes, and remember, it was only for a year. We had to be quick and start the search for a new director. And hiring a director in an academic institution is not that easy. I remember I was asked at the same time to sit in a select committee that was going to help the Lund Commission [on the secret services in Norway], and I said no to that. And people told me: ‘You cannot decline that!’ But I had to make some choices. So, I guess I am quite determined and conscientious – and I did see that director job as an opportunity. I guess I was even quite flattered.

Did you enjoy it?

Yes, very much. We also speeded up the process of getting a new director, which became Dan Smith. And when he had been selected, it must have been around February 1993, I had to tell him – I guess this was becoming a tradition: ‘Dear Dan, I’m having another baby.’ That was the first thing I told him! And on top of it all, the pregnancy was not going too well. So, I had to ask him to start earlier than planned. Our original plan was for him to start in autumn 1993, but he actually started coming to Oslo and overlapping with me in late spring.

But the pregnancy did end well.

Yes, Henriette arrived in October – around the same time of year as the others!

Meeting Three Good Men

Let us go back to your fights with the Foreign Ministry. As we have already heard, some people have been quite important to you. One of them later became Foreign Minister, Knut Vollebæk. Tell us about him.

I have experienced that there are some people who, quite independently of their political party affiliation or standpoints, can effectively cut through the red tape and the challenges and make decisions that are morally right. I can mention at least four of them, and we can start with the one you just mentioned: Knut Vollebæk. Already in 1987, as I pointed out, he was the one who took me aside before that troublesome meeting and assured me that things would probably work out. I remember that when I would sit in the ministry’s library working on my doctoral thesis in the early 1990s he would stop if he saw me and say: ‘Hilde, remember to call me in advance if I need to bail you out again!’ He always had that basic respect for the independence and integrity of the historian and the researcher, and that continued later, after his time as Foreign Minister, when he was ambassador to the US.

There are some people who, quite independently of their political party affiliation or standpoints, can effectively cut through the red tape and the challenges and make decisions that are morally right.

Then there is Vidar Helgesen, from the Conservative Party, who was State Secretary (Deputy Minister) in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the time when there was so much controversy around my research on the Oslo Process and Accords in the early 2000s. He made sure, against all the resistance among several within the bureaucracy, that my report was released. I will come back to that.

And then there is another, who contacted me as these storms were ongoing and I was in real trouble. I remember our eldest daughter Katrine one day took the phone and told me, ‘There’s a man called Stoltenberg who wants to talk to you’. I picked up the phone and he went, ‘Yes, this is Thorvald Stoltenberg’, and this was while his son Jens was Prime Minister, and I had of course interviewed Thorvald previously. Now he called me to say that, ‘Well, you know, with Jens being Prime Minister and everything, it’s hard for me to really say anything, now that you’ve stirred up all this trouble with your research. But I want you to know, from Jens and myself, that it is important to be able to look oneself in the mirror every day and do what is right!’

Interesting – sounds like Thorvald.

Jens even said to me a few times, whenever I met him on some occasion: ‘You know, Hilde, my dad often talks about you at home, and he always speaks so highly of you.’ It took some courage to tell me that, because I was not particularly popular within the Labour Party at the time, to put it diplomatically.

Jan Egeland, ‘The Saviour’

Yes, this is basically about understanding one’s proper role, isn’t it? What about Jan Egeland in the midst of all this. When you started out at PRIO, you and he were there together as master’s students, right?

Hilde Henriksen Waage presenting a report on the Oslo Accords, with Jan Egeland, who had been active in the process, commenting on the findings. Photo: Tor Richardsen / NTB Scanpix

Yes, Jan could certainly be mentioned as a fourth politician who has made a difference to me. I remember when we sat there in the 1980s, when PRIO was still down by City Hall in Rådhusgata 10, and the noisy trailers went straight through that street – that was before the tunnels and everything. The office building was shaking, we often could not hear what we were saying. He was writing his political science thesis, and I was writing my history thesis.

And I remember him saying, as he was writing on the role of small states in world politics and I was writing on Israel and Norway: ‘Hilde, you know, this academic life is not really for me. I think I’ll go out into the world and create some peace.’ It’s true! I mean, already then, he was travelling around the world. He was active in Amnesty, he had been to Colombia, he was a news anchor in NRK, and he was tanned and handsome. And always so nice! A really inspiring person. And I remember answering him: ‘I agree, this academic life isn’t really for me either. And writing this thesis is so tough. Maybe I should just stay home and raise children.’ And he replied: ‘I don’t believe you! In a few years you’ll be a Middle East expert.’

And he was right!

Well, I know Jan, so I may be biased. But whenever I came across him in the materials about the Oslo Process, I saw that he had a real and genuine wish to create peace. I even wrote a book chapter about him once, which I wanted to call ‘The Saviour’, but the publisher wouldn’t let me. The thing about Jan in this context is that when my research started appearing on the Oslo Process, he was open and absolutely willing to answer questions, and he admitted that while their ambitions for peace were real, they had in many respects failed. In short, he was able to reflect critically on his own role. And that takes some guts.

I actually remember a meeting we had in Fuglehauggata, where you presented your first report on the Oslo Process, and Jan Egeland was there as member of the panel. And for me, knowing a bit about the tensions you had experienced vis-à-vis the Foreign Ministry and the Labour Party, it made an impression on me when Jan said so clearly that these things have to be spoken about and questioned. I mean, he was someone who was clearly associated with the inner circles of the Labour Party.

Yes, you are right. He had been State Secretary (Deputy Foreign Minister) and had definitely been part of the Oslo Process.

Fellow Historians

Let’s go back to PRIO as a workplace. It’s been filled with some interesting people, right? And among them are several historians, such as Tor Egil Førland and Stein Tønnesson. What is the place of historians and history at PRIO?

To answer that I will have to go back to Nils Petter Gleditsch. Due to his work on NATO and secrecy and all of that, he was deeply interested in genuine historical research, gaining access to secret sources, and analysing them. Hence, when I came to PRIO, there was much historical research going on. There was Morten Aasland, who is now in the Foreign Ministry and is ambassador to the African Union, there was Roger Sørdal, who was writing on U2-flyovers and spy balloons, and then there was me. There was Stein, too, but he had already been there for a few years (1980–82), had just completed his master’s degree, and left PRIO around the time I came. But he was certainly someone I knew of and in a way took over from at PRIO, although I hadn’t actually met him.

And Nils Petter continued to recruit historians: Tor Egil Førland, now professor of history at the University of Oslo, who was writing on export restrictions and CoCom [the ‘Coordinating Committee’; the Western bloc’s organ for strategic export controls], and Olav Njølstad, who was writing a thesis on Jimmy Carter’s containment policies. Olav is now the Director of the Nobel Institute. I remember Olav and I shared an office down in Rådhusgata. And Stein came back in 1988, after three years at the Institute for Defence Studies (Institutt for Forsvarsstudier). So yes, it’s true, there were many historians. There was Odd Arne Westad, too. He was one of the COs (conscientious objectors) and in a way a junior to the rest of us. But he has gone on to great things – he recently went from Harvard to Yale. All of us found ourselves in this environment around Nils Petter Gleditsch and Helge Pharo.

Fitting in at PRIO

Exciting. But tell me, what was it like being a woman at PRIO?

Well, we are in the past century, right? And there have been a number of changes to what it’s like being a woman in what is still, although not as predominantly, a male-dominated environment. I will admit that I felt a bit of an outsider when I came to PRIO. It occurred to me that most of the women who were there – or who had been there before me – were quite radical feminists, and here I came with my family and kids and everything. And my main cohorts were these male historians who could come across as super-clever, a bit arrogant, and quite good at showing off – or so I felt. But those guys, you know, who are today the Nobel Institute Director and the Department Chair at Blindern and so on, they must have liked me – if not personally, at least as a historian.

We even founded a small club, which we called ‘Internasjonalen’ [The International, after the famous Socialist anthem]. That was Olav Njølstad, Tor Egil Førland, Stein Tønnesson, Odd Arne Westad – and me. I may not have fit in completely, but I did hang out with these guys and continued to work as hard as I could while wondering: Do I really fit in here? Maybe I should just stay home with the kids? I guess what really made a difference was this deep interest in history that we all shared.

I really don’t feel it has been difficult being a woman at PRIO. […] People at PRIO generally are preoccupied with equal rights. But overall, in society at large, things have clearly changed since the 1980s. I recall [my husband] telling his colleagues he had to pick up the kids in kindergarten, and being asked: ‘Don’t you have a wife to do that kind of thing?’

You were at PRIO from 1984 to 2005, before moving on to the university. Did conditions for women change over that time?

Well, to be honest, in spite of what I just said, I really don’t feel it has been difficult being a woman at PRIO. Remember Nils Petter, who thought it was so nice I was having this baby, right? Also, people at PRIO generally are preoccupied with equal rights. I guess it has been more difficult being someone a bit from the outside, from this bourgeois, Christian environment in Drammen, and also not being part of any academic elite. But overall, in society at large, things have clearly changed since the 1980s. I recall Geir working as an entrepreneur and telling his colleagues he had to pick up the kids in kindergarten, and being asked: ‘Don’t you have a wife to do that kind of thing?’

Hilde Henriksen Waage presents a report on Norway’s role in the peace process in the Middle East from 1993–1996: ‘Peacemaking is a Risky Business’. Others pictured are from left: Jon Hanssen-Bauer, Stein Tønnesson and Nils Butenschøn, April 2004. Photo: Håkon Mosvold Larsen / NTB Scanpix

Good Directors – Necessary Changes

So, tell us about the PRIO directors you have worked under.

That’s a funny story. Because when I came to PRIO in 1984, it was something of a hippie institute, with a flat structure and the secretary getting the highest pay of all. We had these common-room meetings for all, where the COs and students were in the majority. We could – and sometimes did – vote down proposals from the tenured research staff. I especially remember one time when I had a visitor over from the Foreign Ministry, and there was one of PRIO’s researchers at the time – I won’t say who – who came with those big, baggy Bermuda shorts and no shirt and sat down in our lunch room with his feet on the table. Things were just floating around, to put it that way. It was quite chaotic, both when it comes to leadership and the organizational structure. Time was ripe for a change, and that is why Sverre Lodgaard was hauled back from Stockholm and SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) where he was working. He came in 1987 and was faced with quite a clean-up task.

Well, for me who came in 1997, I still heard about all of that, the most visible result of it probably being the punching machine for logging hours.

Yes, that was one of the most visible manifestations, but there were so many other things: the salary system, the titles, the director, clothing expectations – I mean, we suddenly started talking about how we were to dress at work. And the punching machine, ahh, yes. For most of us that was pretty strange. Were we to stamp in and out like workers in a factory? All in all, though, I do think it was necessary to meet the demands of the times.

The directors during your time at PRIO have all been different personalities. What can you say about them?

I would say that PRIO has been very good at recruiting leaders who have been right for the times. It was necessary to have a Sverre Lodgaard who could put things in order. It was then necessary to have a Dan Smith who could open up for Foreign Ministry and other sources of funding, which in turn made it possible for PRIO to expand and continue its activities. And it was necessary to have a Stein Tønnesson, who could consolidate our activities so that we did not grow too much, not least when it comes to politically operative projects, instead emphasizing PRIO’s strength as a research institute.

What about the external profiling of PRIO?

This has definitely been strengthened under Stein and later Kristian (Berg Harpviken) and Henrik (Urdal), who speak Norwegian and know how central PRIO ought to be to the Norwegian public debate. That was a key part of Stein’s mission – to make us visible not just as researchers, but as contributors to public debates about international politics.

And during much of this time, you were the deputy director.

Hunting for Funds

That is right, from 1992 until I left PRIO in 2005. Fundraising was an important part of my work all that time. Under Dan, that became a core part of our activities, but in many ways, it was strengthened under Stein due to the emphasis on PRIO becoming even more visible in the public eye.

And that reminds us of an interesting topic: namely, PRIO’s need to be visible, not just due to financing and fundraising, but also because we need and want to share our research findings. To me personally, that has always been an important part of PRIO: the encouragement to be visible, without any sort of central censorship from PRIO’s leadership. And that certainly brings us back to your research. You, after all, became part of a very public and visible debate about Israel and the Oslo Accords.

Well, we could have a long interview about this one topic, because this is immensely important in my view. On the one hand, PRIO is absolutely dependent on external funding, and I have myself had two major projects financed by the Foreign Ministry. On the other hand, this can get quite difficult, because one may get into conflict with one’s funder – as happened to me vis-à-vis precisely that institution, which was also PRIO’s most important funder.

Exactly, and that takes good leadership to guide a way through such a situation.

Indeed: one has to protect the integrity and freedom of the researchers. That was crucial to me, particularly as some of my research became so controversial, both in parts of the Foreign Ministry and within the Labour Party. I mean, when the Foreign Ministry indicated that I should change or tone down my conclusions, that was when I said a clear and unequivocal no.

This brings us back to your master’s thesis, which was more controversial, I guess, than your doctoral work. Tell us a bit more about the controversy with the Labour Party.

Well, a good example is the May 1 Labour Day parades in 1956, when one of the parade floats displayed a living birch tree with a bloody axe wedged into it, accompanied by the following text: ‘Let Israel live.’ I found out through my archival research that this parade float did not come from the Labour Party headquarters at Youngstorget in Oslo. It came from the Israeli Labour Party and the Israeli Foreign Ministry, which shows that the latter actually had a hand in deciding what would be the Norwegian Labour Party’s message.

I guess Haakon Lie, the long-time Secretary General of the Labour Party, was crucial here.

Oh yes, he was the most important of them all, facilitating close contact with the Israelis, and starting negotiations on the export of heavy water to Israel, so that they could build an atomic bomb. We even have the story of the 34 Vampire airplanes, which Haakon Lie wanted to smuggle over to Israel – we do not even know where they ended up.

But still, the main conclusion, that the Labour Party supported Israel, is relatively well-known, isn’t it?

Yes, but I think in the 1980s and 90s, at a time when Norwegian public opinion was starting to turn around, it was difficult for many within the Labour Party to admit that they had been such strong supporters of Israel.

Back to your continued research: did you never lose interest in the Middle East, and think, hey, I’ll study Venezuela instead?

Not at all. I think many of us researchers get a little obsessed. Especially when we get to work on things that are genuinely topical and right at the centre of the news. That is a privilege in so many ways. I felt that I did not do research solely for my colleagues at the university. Quite the opposite: the public at large really cared about these issues. To make it even more topical, I wrote my doctoral dissertation at the same time as the Oslo Process was happening. I remember that right after I had defended my doctorate in February 1997, Dan Smith came to me and said, ‘Well, now we’ve shielded you long enough’. In other words: go out there and get a funded research project! And obviously, I had to turn to the Oslo Process and the Oslo Accords. I was really curious: how was it that Norway, still in many ways Israel’s best friend from the old days, was supposed to have got on equally well with the Israelis and the Palestinians?

I came to PRIO in February 1997, and I remember that on my second week here, you defended your dissertation. And I was thinking, wow, this is fantastic! What a place! Talking about funding, though, where did you get funding for the Oslo project?

We went to the Foreign Ministry. I remember Dan Smith really wanted me to move into more contemporary studies on the Middle East, and this was the obvious thing to go for. So, I got in touch with the people doing internal evaluations at the ministry, and we took it from there. We had several meetings before we got the contract signed in 1998, and it seemed to us that some at the ministry really believed it best that the ministry itself do the full evaluation of both the politics and the use of funds for the Oslo process.

PRIO researcher Hilde Henriksen Waage presented the report ‘Norwegians? Who Needs Norwegians?’ on Norway’s role in the Middle East before the Oslo Process. Former Prime Minister, Kåre Willoch, gave comments (pictured left), January 2001. Photo: Tor Richardsen / NTB Scanpix

But we did get project funding in the end. What they did, though, was make it into a two-phase project. The first part, to be undertaken between 1998 and 2000, would be about how Norway got engaged in the first place. That part of the project was under the title Norwegians? Who Needs Norwegians? And then they did not really commit to the second part. That came later, after quite a lot of noise.

The Oslo Process

There is indeed a lot of noise stirred up throughout, here! But first, a short digression: there is a play called Oslo, which has become quite popular. It’s about the Oslo Process.

Oh, dear.

Has the author of the play taken your findings into account?

Not at all. I mean, I do read newspapers. And I have read several stories about this play – how the writer had a child in the same class as Mona Juul’s and Terje Rød-Larsen’s twins in New York, and how he got so fascinated with Terje Rød-Larsen’s own story about his role. That play really constitutes the fairy tale version of the process. It reproduces all the myths about Norway’s role. And I have come to realize that even though I have published so many academic articles on this subject, and have gone in depth into the details of the process, I will never be able to change the way these things are perceived internationally – and even really in Norway.

So, if someone who had seen the play wanted to know exactly where your story is different from the one portrayed in the play, what would you tell them?

Well, ‘the fairy tale version’ – as I call it – is that the Oslo Process is primarily Terje Rød-Larsen’s achievement. He decided that he would try to do something that no one had been able to achieve: create peace in the Middle East. That is when I would say: that is not how politics or peace diplomacy works, and that is not the way in which peace negotiations take place. You cannot just show up in Jerusalem and say: ‘Hi, I’m Terje. I come from Norway, let’s make peace.’ It is just not possible.

And I find it strange that people believe in such a version. I would immediately add that Terje Rød-Larsen has played an important role, with his initiative and his way of approaching the whole situation. But that is not how it began. Because someone had been working on this for years. And that someone was the Norwegian Labour Party, which for years had worked systematically to position itself in that role. But in the play, that is completely swept under the carpet, and it becomes a one-man show with that man’s lovely wife as a helper.

The play ‘Oslo’ presents a ‘fairytale version’.

The Missing Counterbalance

That takes us back to the Oslo Process as such. You have always claimed that one must take power seriously. Israel is the stronger party, and the stronger party will formulate most of the premises. I guess your claim is that this is where we often go wrong – that we do not do enough to even out those power discrepancies.

Yes, that is a position I have always held. And it is hard for me to understand that people can get so angry with me over that. I simply point out that there is a real asymmetry of power! As I have already said, there is a strong party and a weak party. And it is simply not the case that a nice little bridge-builder like Norway can easily change the policies of the stronger party, particularly when that party is backed by an even stronger one, the United States. I can’t see what on earth is so sensational about pointing that out. But in my case, making that factual point is what created all the noise around my two reports. But of course, my conclusions did not feel flattering for Israel, or for the Norwegian governments and the Norwegian Labour Party.

What have the reactions been like in Israel? I am not thinking of those who are in active politics and may have something to defend, but of researchers and others who know the Oslo Process and history well.

Ah, I remember coming to present my findings at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and I was so nervous. I thought: ‘I may have been in trouble for my research conclusions before, but I’ll surely get a real beating now.’ But that didn’t happen. Israeli academics, even Israeli politicians, have a much more ‘realpolitik’ approach to all of this. So, the first question to come up after the lecture was this: ‘Of course we Israelis are the ones deciding, who else should it be?’ So that actually went very well – I got much support. It went considerably worse on the Palestinian side, and I was not prepared for that either. Many of those I interviewed among the Palestinians, and those I later shared my findings with, were angry. Maybe that reaction is not so strange when having to admit that they had entered into a deal according to Israel’s rules of the game, and based on Israel’s premises, because they were so weak.

What about the United States in all of this? They are obviously the strong party behind Israel. But are there not periods in US politics where they have exerted more pressure on Israel, too, such as under George H. W. Bush?

That is exactly the discussion I want to encourage. The moment that American administrations, whether Democrat or Republican, see that this one-sided support of Israel hurts them, you will see that they are willing to shift course. We saw it with the Eisenhower administration in 1953, and during the elder Bush’s presidency, as you said, in 1991. They took new initiatives, and they criticized and corrected their close ally Israel. So please note here that I am not saying peace and a new direction for the Middle East are impossible. But those two instances are exceptions. Mostly, American presidents have moved the US in an ever more Israel-friendly direction, which makes peace less likely.

Joining the University and Learning Hebrew

In 2005, you left PRIO for the University of Oslo, maintaining a 20 percent link to PRIO. Was that an obvious step for you, or a hard decision to make?

Oh, it was very hard. I had been at PRIO since 1984. I had taken on a whole spectrum of roles at PRIO – from being a cleaner to becoming its director. And I felt, and still feel, that PRIO is a fantastic place to work, with such excellent colleagues, such a good environment, and so much fine leadership, which not least has helped us all understand that we must work hard on financing all our research, because PRIO does not have its own money. But at the same time, PRIO manages to take care of each individual researcher. Indeed, I have so many good things to say about PRIO that I could give a long lecture just about that. But I felt that all the noise around my work was making it more problematic to stay on, both for me and for PRIO. It was not that I did not get support internally, because I received strong support from everyone at PRIO. There was no one there who did not wish for me to stay on. But with all the heated discussions around my work on the Oslo Accords, I did feel it was becoming more difficult.

Hilde Henriksen Waage and Gregory Reichberg at a cleaning Dugnad at PRIO in Fuglehauggata, 2004. Photo: Håvard Bakken / PRIO

So, when a professorship was announced at the University of Oslo, with a start date of August 1, 2005, I applied and went for it. Remember, I had studied for three years in a teacher’s college, and my aim was always to be a teacher, not a researcher. For as long as I can remember, I have always enjoyed communicating and teaching. The funny thing is, I had always imagined that in order to be a professor of history at the University of Oslo, you had to be a man and be 60 years old. When I realized there was actually an opening for me, I knew I had to give it a try. But it was with a truly heavy heart that I handed in my resignation at PRIO. I was crying. And Stein Tønnesson, our director then, was not too happy about it.

The rest of us were not too happy either. That has to do, I think, with your ability to care for your colleagues and your fellow human beings. That is something people do emphasize about you. We celebrated your 40th birthday not too long ago, right? Or I guess it was 60. Anyway, it made an impression on me how everybody talked about your love and care for the people around you – colleagues, students, family, and friends. You are also a good listener. And on top of it all, you have had your share of serious health challenges – with your eyes, and with respiratory diseases, among other things.

Sometimes you even have problems with reading or driving, and often have to spend parts of the year locked up in Gran Canaria, because the Norwegian winters get too cold. For someone who loves her family so intensely, that cannot be easy. And still you stay so engaged and positive. Where does that come from?

Well, thanks, but I really do not know. It is true, however, that I like working with and being close to people, and not least interacting with students and young researchers. That is true whether it is a young Henrik Syse coming to the institute in 1997 or my students coming to me today. I really love engaging with other human beings. It gives me a lot as a scholar, too. I learn so much from others, including from my students; not just by lecturing, but also by advising, commenting on papers, leading seminar discussions, and helping students finish their theses. And I do suppose it is true that I spend quite a lot of time on my students.

Yes, you do. But what if a student comes to you and wants to write a thesis that challenges your conclusions. How would you feel about your job as adviser then?

Oh, that is just fine – great. I may feel inside that this student will not actually manage to disprove my findings unless he or she has found some documents I simply did not know of. But under all circumstances, I would find that exciting. I should add, though, that I feel I have left behind my research on Norway’s role in the Middle East now. I have moved into other topics, even if they are related. Right now, I do quite a lot of work on peace negotiations as such. That builds on my work on the Oslo Process, which I learned so much from and take inspiration from. But it goes beyond that. What happened in the peace negotiations after the war in 1948, or after the wars in 1967 and 1973? What happened when Syria invaded Lebanon in 1976? These are genuinely exciting topics, because I find that what happened internally, and the agreements actually reached, are not at all the way they have been portrayed to the outside world.

Let me add that one of the really great things for me, since I do not have time to dig into all of these archives myself, is to send young master’s students to do research in, say, the Carter archives, or the Reagan archives. And now I have taken a bachelor’s degree myself in modern Hebrew, so that I can much more easily access the materials in the archives in Jerusalem.

Fantastic, a bachelor’s degree in modern Hebrew.

No, it’s not fantastic at all. It’s crazy, that’s what it is. It is very difficult to learn Hebrew, a Semitic language, when you are a Norwegian. But it has been a great help to me. Now I can access and understand so much more of those archives in Jerusalem.

Hilde as an exchange student at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, July 2015. Photo: Private archives

We are getting towards the end, Hilde. Just let me say what an incredibly journey you have been on – and have shared with us. Let us finish now with your family, which means so much to you. They have supported you all the way.

Yes, absolutely. I sometimes feel as if my husband Geir and the kids have been along for the ride, to put it that way. They have certainly not chosen this voluntarily. At times, there has been a fair share of phone calls, even death threats, and police claiming I need protection. Often, our children have taken those phone calls, so they have heard it all. Their childhood was filled with comments about this mother of theirs. Remember, I was quite visible in the media, more so then than now. They had to live with that.

But as one of them once said to me: ‘We’ve never had any other mum. This is what we’ve grown up with – I mean, we thought that everyone sat listening to the foreign-policy news hour on the radio at breakfast on Saturday mornings, with their mum hushing them so she could hear everything.’ So, to them, this life has not been strange at all. Even when others have asked them, ‘Aren’t you afraid something might happen to your mother, working on all these dangerous things?’ They have answered: ‘Nah, mum says it’s nothing to worry about, and we talk to her on the phone every day.’ Having said that, of course Geir has had to hold the home front together with three kids, when I have been on these research visits to the Middle East.

And in 2020, you have your 40th wedding anniversary!

Yes, indeed. It is actually our anniversary tomorrow, the day after this interview. But that is just 39.

If we can finish up by having you say one important thing about PRIO that you have taken with you, one thing that has really made an impression on you, what would that be?

When I come back here now, in my 20 percent position, and we work on applications, for instance, I see how much people help each other. In spite of all the pressure and the dangers of not succeeding, we do support each other. PRIO could have been a very, very stressful place. And naturally, there is stress at PRIO. But still, there is a solid framework here, and extremely good leadership. That trickles down into the entire organization. Quite simply, and in general, people are kind to each other.

Thank you, Hilde!

I found this interview very interesting and educating. The issue of power dynamics. I have always been interested in Israel from the biblical point of view and a bit of history. After reading this interview I now want to know more.

Great story!