On September 29, 1919, in Phillips County, Arkansas, a deputy died while trying to break up a labor meeting of black farmers. The next day rumors swirled about an impending black insurrection. In response, a white mob of up to 1,000 strong formed and indiscriminately attacked blacks across the county for three days. Federal troops, requested by the governor to put down the violence, may have assisted and even taken part in the massacre. And the newspapers went along for the ride, publishing false stories about plots to massacre whites.

In reality no uprising took place. Instead, up to 240 black Americans died at the hands of white Americans.

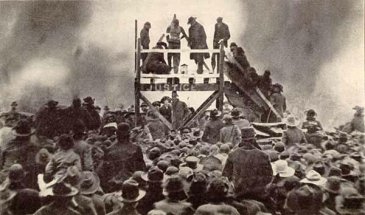

The 1893 public lynching of black teenager Henry Smith in Paris, Texas

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement is confronting this legacy of white violence against people of color and in particular African Americans. It is a living legacy that continues to claim the lives of black men and women such as George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. While the killing of people of color receives the bulk of attention there are growing calls to address the racial inequality gap created by hundreds of years of violence and repression.

The statistics are staggering

The median household income for whites in 2016 was close to $150,000, for blacks it was around $13,000. Homeownership, one of the largest sources for building wealth, is far lower for blacks, close to 40%, than whites, around 80%. The US fares little better when it comes to African Americans having sufficient income for basic needs. More than 20% of blacks are considered to be living below the poverty line compared to 9% of whites.

Even if African Americans take routes that are suppose to lead to greater income and wealth, it doesn’t seem to abate economic inequality. Higher education is considered the great leveler of the playing field. Bachelor’s degree holders earn about $30,000 more than those with only high school diplomas. Black college graduates do earn more than other blacks without a degree. However, blacks that hold degrees still make less than whites with only a high school education and earn three times less than whites with similar degrees. Owning a home also doesn’t pay off in the same way for blacks as it does for whites. Black Americans have higher mortgage rates, even when credit scores are taken into account, and their homes appreciate less than whites. No matter what, black wealth still lags.

This is only the latest iteration of campaigns to eliminate the racial inequality gap. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1967 pointed out its dangers to democracy and called for an economic bill of rights that guaranteed jobs and income as well as greater access to housing. In 1965, United States President Lyndon Johnson, addressing the commencing class of Howard University, declared that “Negro poverty is not white poverty…” and promised greater social programs to overcome centuries of oppression. Frederick Douglass in 1856 campaigned against the perils of capital accumulation and viewed the government as a means to redistribute and create a more egalitarian society.

Why racial inequality persists

Why racial inequality persists in the US despite rising living standards and African Americans “lifting themselves up by their bootstraps” is attributed to white supremacy. For centuries blacks worked as slave labor, generating wealth for whites. In 1865, the 13th amendment abolished slavery and granted citizenship to all former slaves. However, in the years that followed Reconstruction, Jim Crow laws maintained racial segregation as well as restricted voter registration across the South. Laws enforced by vigilante and state violence, many times indistinguishable, effectively created a caste system. In towns across the North, black residents fled under threat from white mobs. In Anna, Illinois, blacks left behind their businesses and homes after a mob lynched a black man accused of murdering a white woman.

Official government policy as well as violence actively prevented black wealth accumulation for much of the history of the US while at the same time assisting whites. Ta-Nehisi Coates suggests that we think of white supremacy as a pirate flag, or the plundering of black wealth by official and unofficial means.

Lynching

Lynching was the primary tool for looting hard earned black gains during and after Reconstruction. Between 1877 and 1950, over 4,000 blacks were lynched in the US. Lynching occurred mostly in the South but no region in the US escaped the tragic violence. Rare before the civil war, due to the monetary value of slaves, they spiked between 1880 and 1890, reaching as high as 150 per year.

Terrifying public and ritualistic spectacles, lynching symbolized a violent rejection and subjection of blacks by white society. Violence inflicted on black bodies acted as a symbolic act in which the victim represented the “crime” of their whole race. It served as a warning to all African Americans not to challenge white supremacy or their role within the exploitative system. The act of lynching became a primary tool in enforcing economic, political, and cultural racial exploitation.

Most victims were murdered without being accused of any crime, killed for social transgressions or demanding their basic rights. However, the economic aspect is often overlooked. Ida B. Wells campaigned her whole life to abolish racial terrorism and viewed the practice of lynching as an “antidote to black success“. While rape and the fear of black sexuality justified lynching, the cause was fear of black success.

Continued suffering

My research shows that black communities exposed to racially motivated violence continue to suffer economically decades later. Though lynchings continue to occur, it mostly faded from American society after the 1940s. Yet, black communities that experienced lynchings in the past are poorer today than communities that did not. Lynchings also continue to impact whites, however, its legacy leads to a reduction in poverty.

The diverging effects of lynching reinforces an idea familiar to African Americans but unacknowledged by the general US public, that white wealth is build on the exploitation of black Americans. Past violence, even hundreds of years ago, reach across generations and continue to shape contemporary economic outcomes.

Black awareness of the redistributive power of violence was recorded as early as Reconstruction. In a Kentucky Freedmen’s Bureau school in 1866, a teacher asked the school children how whites gained so much power in the US. The children replied money. When asked how they obtain such large amounts of money the school children replied “Got it off us, stole it off we all!”.

The broader white community

There is another false narrative that only a minority of Southern white extremists were culpable. However, the broader white community sanctioned and embraced the act of killings.

Taking part in collective violence was a means to signal both black subjugation and white immunity. Attending whites created a carnival like event for the collective killing. They attracted large crowds, in one case attracting as much as 15,000 spectators in Waco, Texas, to witness the announced killing, torture, dismemberment, mutilation, and burning of victims. Vendors sold food, photographed the event and corpse, while participants removed body parts that served as souvenirs.

Newspaper announcements and photographic evidence produced by the white community suggests wide acceptance and participation. “Whole families came together, mothers and fathers, bringing even their youngest children. It was the show of the countryside, a very popular show,” reads a 1930 editorial in the Raleigh News and Observer. The editorial continued, writing that “men joked loudly at the sight of the bleeding body, girls giggled as the flies fed on the blood that dripped from the Negro’s nose.” The joking and giggling white men and women were ordinary and respectable with a deep belief in defending and maintaining white supremacy for the benefit of all white people.

Blurred lines towards state violence

The events often blurred the line between state and non-state violence. While lynching is often viewed as a vigilante act operating outside the state’s justice system, this is an inaccurate account of lynching in the US. In many cases, law enforcement assisted and abetted mobs. In fact they were often the same people. Officers would regularly leave a black inmate’s jail cell unguarded after rumors of a lynching swirled, allowing a mob to kill them before any trial could begin.

It went beyond looking the other way. Arthur Raper, studying 100 acts of lynching, estimated that police officers participated in their official capacity in about 50% of those events. In the case that attracted a crowd of 15,000 in Waco, TX, both the mayor and chief of police attended.

Consequences for survivors

Communities that survived continue to feel the consequences of violence. Families are less able to purchase food, medical care, childcare, and adequate housing. Those living below the poverty line face increased adverse outcomes such as poor health, criminal activity, risky behavior such as tobacco and alcohol use, high teen births, incarceration, and reduced school performance. Not only does it affect individuals and families but it also impacts broader society. Recent studies have shown that higher rates of poverty are associated with lower rates of growth in the economy as a whole. Poverty might even have the potential to undermine democracy.

As a means to bring attention to this exploitation, anti-racist movements have targeted statues of figures that built their reputation and wealth on the subjection of people of color and indigenous communities. Statues from Edward Colston in Bristol to General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson in Richmond have been toppled or defaced, raising questions of why society venerates such figures and disregards victims.

Remembrance, acknowledgement, reconciliation and reparation

When it comes to remembering survivors, there are few public memorials on African American suffering post-slavery. In Paris, Texas, a Confederate memorial sits on the courthouse lawn but there are no markers to document the lynching of a seventeen-year old black boy named Henry Smith in 1893 or brothers Irving and Herman Arthur in 1920.

The lack of acknowledgement adds to a sense that black life is not as valued as white life.

Remembrance adds to a more complete picture of black struggle for equality in the US but it also suggests a path for addressing one of the most endemic problems within the US. Understanding that racially motivated violence not only contributes to African American marginalization but also to wealth accumulation creates policy implications at the government and community level.

Remembrance, reconciliation, and reparation, moves the past out of the shadow of Phillips County or Tulsa, Oklahoma or Rosewood, Florida, and into an environment where addressing its legacy strengthens communities.

I don’t agree with some of this but willing to understand what’s broken and help fix..