As ongoing post-electoral violence across West-Africa continues, especially in countries such as Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire, the region is forced to urgently address the implications of long-term economic decline and poor governance systems.

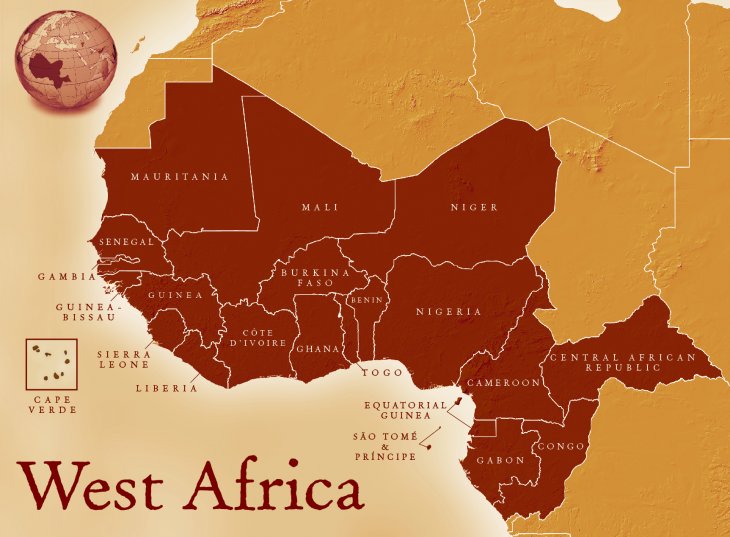

“Map of West Africa” CC BY

What are the key driving forces for the current troubling political atmosphere?

Post-election Violence: Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire

2020 has been the year of many political battles across West Africa, as more than five of the region’s countries were set for presidential election, including the Francophone states of Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire. An announcement by electoral commissions in these two nations on October 24th and November 3rd respectively showed a win of 59.5% of the vote for President Alpha Condé of Guinea and 94.27% for his colleague Mr. Alassane Ouattara in Côte d’Ivoire. These victories, which meant that the two presidents had secured controversial third terms in office, came days after violent protests with police firing tear gas canisters at demonstrators in streets across Conakry and Abidjan.

What makes these two elections interesting is their similarity when it comes to several factors including the following:

Let’s start with the first factor.

Manipulation of the Constitution

After decades of military rule and political turbulence, Alpha Condé became Guinea’s first democratically elected leader in 2010. Before assuming office, Condé had been a long-standing opposition figure who had criticised the ruling regime for lack of democracy. Many of his supporters were therefore shocked when the 82-year-old Condé decided earlier this year to push through a new constitution that would allow him to run for a third term. Since the announcement of this referendum on the constitution changes, Guinea has witnessed nationwide protests, often led by the opposition candidate Cellou Dalein Diallo.

Meanwhile in the neighbouring country, Côte d’Ivoire, soon after Mr Condé’s successful third term bid in October, critics pointed out Ouattara’s decision to run for another term as a new blow to West African democracy. This occurred less than three months following a military coup in neighbouring Mali in August. Similar to Condé, Ouattara had also been in opposition and gained power in Côte d’Ivoire following the 2010 presidential election that had resulted in a civil war and the killing of up to 3000 people. His decision to run for another term has led the world to doubt West African states’ ability to consolidate democracy. While opponents of the 78-year old Ouattara have claimed that he broke the law and the two term limit proclaimed by the constitution, Ouattara disputed that he decided to run again for another mandate under a new constitution approved in 2016. Côte d’Ivoire’, which is the world’s top cocoa producer, has made great economic progress in the past years. However, the recent situation has made people question how long this economic prosperity will continue to last.

The situation in Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire highlights a continuous backward pattern of democratization currently witnessed in around the world today. In these two specific cases, the paradox is that the first protector of the constitution became the first violator of the rules of the constitution.

Election Dispute and Opposition

Since the announcement of the elections results, the streets of Conakry and Abidjan have seen little signs of peace. With massive violent protests led by the oppositions and their young supporters, this is a political crisis many saw coming. Doubting the transparency of the electoral authority, Guinea’s 68-year old opposition leader, Diallo, who had declared himself the winner of the first round, accused the incumbent Alpha of electoral fraud, irregularity and breaking the law to hold on to power. With the result showing only a 33.5% win, this has triggered confrontations between security forces and Diallo’s supporters who primarily come from the Fulani ethnic group. Recent event shows that Diallo, who filed a complaint with the Constitutional Court, lost the legal battle against the incumbent.

Meanwhile in Côte d’Ivoire the unrest related to the election has so far killed up to 35 people, and for many brought back painful memories of the 2010 civil war when Ouattara’s predecessor Lauren Gbagbo refused to step down after defeat. Despite complaints of irregularities and fraud accusation made by the main opposition candidates, including former president Henrik Konan Bedie and Prime Minister Pascal N’Guessan, their joint effort to boycott the vote has massively failed.

Likewise, it is important to mention the role played by social media in these contexts. In both cases, social media have been used by the political oppositions to mobilization and coordinate their supporters locally and nationally. It has also enabled the oppositions to gain international attention and amass support for their causes. On the governments’ side, crackdown on internet and social media has maximized their suppressive tactics when it comes to dealing with the opposition supporters. For example, in Guinea, cutting of the internet, international calls and social media was used as a tool by the incumbent president Condé to suppress street protests in opposition strongholds.

Ethnic Polarization and Resource Curse Syndrome

Both president Ouattara and Condé are from similar ethnic groups, often referred to as Malinke in Guinea and Jola/Madinke or Dioula in Cote d’Ivoire. After years of violent conflict between the South and North (where the marginalised Jola are based) which ended following the 2010 civil war, Ouattara was elected as Côte d’Ivoire’s first Jola and Muslim president. The Jola are the country’s second largest group and make up around 27.5% of the overall population of 26 million.

Meanwhile in Guinea, Alpha Condé continued the legacy of the politically dominant Malinké ethnic group. This group has ruled Guinea since the independence led by former president, Ahmed Sekou Touré in 1960s. Continuing this legacy meant that Mr Condé had to find a way to reconcile with Guinea’s largest ethnic group, namely the Fulani, who make up around 33% of the population compared to 31% of the Malinké. Understanding the ethnic dynamics within these countries can be very helpful in analysing the high ethnic polarization shadowing the two current elections. In Guinea for example, ethnic tension remains between the opposition led by Cellou Dalein Diallo supported by the Fulani and the newly re-elected President Alpha Condé, mostly supported by the Malinké and other ethnic groups.

Nonetheless, is fundamental to comprehend that in West Africa, precisely in the Francophone countries, having political power is often seen as the only way to access the country’s resources. This pattern has significant implications for whoever is in power, their ethnic belonging and redistribution of the nation’s wealth. As the narrative concerning the ethnic group in power being directly in charge of the country’s resources continues, this leaves many of the ethnic polarized countries within the region at risk of witnessing high ethnic tension during election period. The unequal distribution of wealth and resource related grievances contributed to Côte d’Ivoire experiencing post-election violence several times, even leading to the 2010 civil war and breakdown of society.

The ingroup fights over limited resources in these countries have been further exacerbated by the pandemic. As borders are closed and movement from one country to another has been drastically reduced because of the global lockdown, the already weak economies of these two countries continue to suffer. The price of basic needs and the rates of unemployment have increased exponentially. With social distancing, schools are closed and most of these governments do not have the financial capacity to provide education to the youth.

Meanwhile, the population numbers continue to increase, especially in the urban areas. For example, in Guinea, with most of the country’s 13 million people living in extreme poverty despite the presence of the world’s largest reserves of bauxite, from which aluminium is refined, various ethnic groups harbour other economic grievances. The country’s youth remain highly uneducated and unemployed. With no hope of economic progress, desperation kicks in and migration over the Mediterranean to Italy becomes the only way out of poverty.

What are the regional implications?

While Guinea is still trying to find a resolution to its political turmoil, the level of post-election violence in Côte d’Ivoire has steadily escalated. The current ethnic tensions witnessed in both countries pose serious threat to the West African region’s stability, as we may see some spill over effects that could translate into cross-border conflicts with complex underlying factors. As the world continues to watch the progress in the two nations, we should not forget that resolving the ethnic issue will be challenging because many of the region’s countries have similar ethnic compositions (e.g. Fulani and Malinké are both present in Senegal, Liberia, Mali, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone as well in Nigeria, Niger, Mauritania). This also indicates that urgently finding a peaceful and economic solution to Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire’s problem should remain a priority not only for regional, but also international actors.

If not, the disastrous consequences of this current political violence trend may be felt across the whole world, and not only in West Africa.

Inequality, poverty are drivers of violence. Politics and leadership in religion has become a source of employment and power seemingly this is what will enable access to resource many are scrambling for it, not as a way or a means to bring development that will benefit the people. There is urgent need to find ways for equitable distribution of resource to curb the escalation of violence.

[…] Condé passing a constitutional referendum that granted him an extended third-term presidency. In a similar bid to that of Mr. Alassane Ouattara of the Ivory Coast, Condé’s third term also sparked violent protests across the country that resulted in gross […]