Kristian Berg Harpviken as Director of PRIO (2009–2017). May, 2017. Photo: Ebba Tellander / PRIO

Kristian Berg Harpviken in conversation with Arne Strand

If we fast-forward to today, peace research – well, actually all research – faces a new challenge that has become more and more obvious over recent years. This is that powerful political forces do not respect the core values that serve as the foundation for research: namely, the obligation to seek the truth and to build logical and consistent arguments.

Peace research has been a success, says Harpviken. Today, the study of war and peace is central to a number of academic fields. The most important finding of peace research is that the extent of warfare in the world in recent decades has been only a fraction of what it was during the major wars of past centuries. The key reasons for this decline are democracy, greater economic equality, international cooperation, and peacebuilding/peacekeeping operations and dialogues. ‘The greatest paradox of our age,’ Harpviken says, ‘is that most of us don’t see any of this, and that more and more we are giving up the things that made the world a better place.’

Kristian Berg Harpviken welcomes his good friend and colleague, Arne Strand (The Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), Bergen, Norway), to his newly built log house at Harpviken Farm, which lies on the shores of Lake Mjøsa, just north of Brumunddal. The two men trace the connections from their shared life-long commitment to Afghanistan to today’s global challenges, via research policy and the important contributions of peace research to our understanding of the world. Harpviken was formerly Director of PRIO (2009–17). His research focuses on Afghanistan and the Middle East, civil war, peace processes, social movements and migration. He has been associated with PRIO since 1993, when he joined the Institute to work on his M.Phil. dissertation.

Education and Interest in Peace

Arne Strand: The first time I met you was in 1989. At that time, I encountered a conscientious objector doing his civilian national service at the offices of the Norwegian Afghanistan Committee (NAC). You stood out slightly from the others doing civilian national service – for one thing, you were quite a bit older. I found out that in fact you’d already run a farm, studied economics, and achieved the military rank of second lieutenant. You were able to draw on your training in economics, and in addition you were studying for a university degree.

You weren’t a typical person to be doing civilian national service, but nonetheless, you’d refused to do your military refresher training. Can you explain a bit about your background and tell us a little about the choices that led you to do civilian national service and be a conscientious objector?

Kristian Berg Harpviken: Yes, so firstly I’d had an interest in international policy and peace and conflict ever since my early teens. I wasn’t a particularly diligent student during my final years at school, but I had some very good social sciences teachers who inspired me and stimulated my interest in international relations. But even so, when I was 18, 19, 20 years old, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do when I grew up. A farm became available within our family, and so I bought it, did a course in horticulture, and worked as a farmer for several years. I’d actually grown up on a farm, but with animal husbandry as the foundation. There was a lot I didn’t know, so it was a steep learning curve, but I really liked practical work and you get to use many different aspects of yourself as a farmer, so it was an exciting time.

For several years, I ran the farm together with one of my best friends. Even so, as time went on and we got our routines established for production, obviously it became a bit less exciting, because it was very much about just continuing along the same track. And quite quickly I became restless intellectually. I started to study a bit of economics on the side, first at the Norwegian School of Management [in Gjøvik] and then at the University of Oslo. And then I decided to lease out the farm. At that point, I’d been running it for five years after finishing my horticulture training. So in that respect, I’m a retrained farmer. Nowadays, my farming experience is in the distant past, but it’s clear that what I gained from it is a way of thinking in the round about a small business and seeing the direct effect of your own efforts on what you can afford when you’re preparing for Christmas at year’s end. So yes, it’s a background that I value very highly, and I’ve gained a great deal from it.

Kristian and Waldemar Zawadzka preparing for planting leeks in the greenhouse at Harpviken farm, 1985. Photo: Ole Martin Stensli

And then, after you had been through military service, you decided to say ‘No, that’s enough!’. Was it then that you got involved in peace studies? Had you gone through a period of reflection that made you decide that you were through with the military? What was the reason that this became a turning point?

Well, I was already sceptical about doing military service even when I originally enlisted. I was in the military all through 1981, and somewhat randomly I found myself in an officer training corps and trained as a junior officer. I got really good at using mortars – I knew absolutely everything about mortars. And it was interesting, I learned a lot in the military. And I was in the company of a lot of interesting people. In many ways, our evenings at the barracks were one extended study circle, where we critiqued Norwegian defence policy and the military’s organizational structure. There was a lot of pacifist debate in the barracks during the evenings. And there were several of us who even thought about becoming conscientious objectors during our military service, although nothing came of it. So I completed my military service and got my second-lieutenant’s star in the post a few years later. But when I was called up to do my military refresher training, my ideas had matured sufficiently that I decided to refuse to serve.

My motivation was purely nuclear pacifism. I thought it was impossible to defend participating in a defence strategy that was dependent on nuclear weapons. It was already clear to me then that Norway was an integral part of NATO’s nuclear strategy. At that time, we had the NATO Double-Track Decision, and in addition, there were developments underway that had the potential to bring about the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons on European soil. It was pretty clear that if global war broke out, it would be played out in Europe with the United States participating from a distance. The victims would be here. With the development of tactical nuclear weapons, the threshold for nuclear warfare would be lowered. And I found that this was something I absolutely couldn’t support. For me, it was unthinkable to take my place in a command structure where I might have to take up arms at short notice on the basis of those principles. So that was my motivation for refusing to serve. And strictly speaking, that’s not a basis for avoiding military service in Norway. Conscientious objectors are supposed to be total pacifists, not nuclear pacifists. But I wasn’t challenged on that point during my interview with the local sheriff. So instead of doing well-paid refresher training as an officer, I spent four months doing badly-paid civilian service. A kind of mild punishment, but actually I got a lot out of it.

It was pretty clear that if global war broke out, it would be played out in Europe with the United States participating from a distance. The victims would be here. With the development of tactical nuclear weapons, the threshold for nuclear warfare would be lowered. This was something I absolutely couldn’t support.

Are the things you do driven by chance events, or do you make deliberate choices? You ended up doing your civilian national service with the Norwegian Afghanistan Committee (NAC). Was that a choice you made, or did it come about by chance? At that time, the NAC was a solidarity organization that wasn’t particularly strongly opposed to the use of force in the Afghanistan conflict.

It had a lot to do with chance. Because I had completed my initial military service, I only had to do four months of civilian national service. And so I found myself at Dillingøy on the Oslo Fjord — home to the renowned headquarters for the civilian national service. There was a large board with possible jobs for people doing civilian national service. Mostly they were jobs at care homes and kindergartens. Very valuable work, but that wasn’t what I was most interested in.

Basically, there were only two jobs that appealed to me. The first, which I put at the top of my list, was at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). The second was with the NAC. I phoned PRIO, which turned me down. I don’t know why. It amuses me now, however, to think about how my first approach to PRIO ended in outright rejection. Perhaps it was because I would only be with them for four months. Or perhaps I didn’t manage to convince PRIO that I had anything to offer. But then I moved on to the second job on my list. You’re completely correct when you say that the NAC was a solidarity organization that explicitly supported the use of violence by the Afghan resistance movement. I’m not sure how much I was aware of that, but if I look back, I do remember the NAC’s posters and their images of resistance fighters, mujahedin, sitting on mountain tops with their Kalashnikovs silhouetted against the sunset. Those images were similar to a more recent genre, known as ‘helicopters at sunset’, which was widely used by the allied forces in Afghanistan after 2001. One rarely sees the victims of war, but instead we get to admire extraordinary examples of technology and uninjured soldiers, all set against beautiful landscapes.

As I see it, I was working at the NAC at a point when we were fairly deliberately moving away from supporting the resistance movement, its commanders and warlords, and towards acting in solidarity with the Afghan people, who were mainly victims of the war. So I can lend my support to that. But something that I’m rather more self-critical about is that we, myself included, to a large extent accepted the conflict patterns of the Cold War and did not see the opportunities, in the context of Afghanistan, for dialogue across the conflict between the resistance movement and the so-called Communist regime in Kabul. Completely to the contrary, we rejected any attempted approaches. Today, it’s easy to see that if we had achieved some kind of reconciliation, a peaceful solution, something that was resisted by both the United States and Pakistan and other supporters of the resistance movement, then yes, Afghanistan could have been a much better place to live in today. It’s a sad story, and I have to shoulder my share of the responsibility.

The Afghanistan Laboratory

I’ll come back to that topic, because in reality your experience at NAC provided you with opportunities to gain insight into, and to experience working within, a conflict – an experience that was completely different to what you would have got by doing your civilian service at PRIO. So what you did next was to continue with Afghanistan. Just a few months after I met you for the first time, you had become my deputy and the NAC’s Agricultural Coordinator.

The direction you chose then, which you perhaps hadn’t thought of as leading towards research, seems to have given you an extremely rich practical background and strong skills with empirical data. This wasn’t what you set out to get originally, but these aspects of your experience developed over time and served as a foundation for the analyses you made when you later went into research. Do you agree?

Yes, and that was an absolutely deliberate choice. I was encouraged to apply for that job, but there was competition to get a job with the NAC at its overseas office in Peshawar, which worked ‘cross border’ with Afghanistan at that time. The thing that was attractive was the opportunity to work practically and make use of some of my skills in financial management, leadership and agriculture. But above all, it was the opportunity to get to know a conflict by living and working within it.

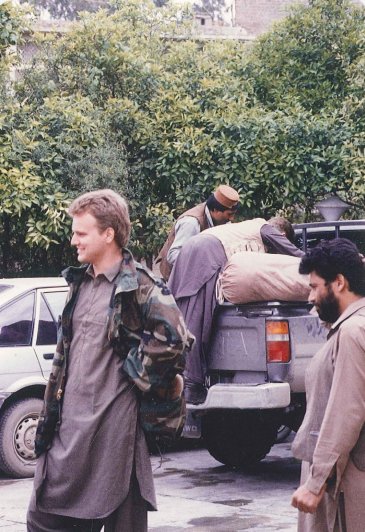

Outside the main office of the Norwegian Afghanistan Committee in Peshawar, packing the pick-up for a field trip to Afghanistan, 1990. Photo: Arne Strand

With hindsight, I’d say that in the almost two-and-a-half years I worked for the NAC, I learned more than during any other time in my life. Really, it was a completely incomparable schooling in understanding peace and conflict and seeing what they mean for people. And perhaps the thing that I take with me, the thing that surprised me most of all at that time, was how to a large extent people continue to live fairly normal lives in an extreme situation. From a distance, one thinks of war as all-encompassing and assumes that everything comes to a halt. But in reality, people continue to fall in love and have children and build houses and for that matter also to lose everything, get sick, and die. In other words, all the things that make up normal life. It struck me that despite the enormous differences on the surface, we humans are all pretty similar.

There are two things that I think we can explore in greater depth. Peshawar, in north-eastern Pakistan, where the NAC had its office, is just across the border from Afghanistan and at that time was the birthplace of two phenomena of global historical significance.

First of all, the resistance movement was based there. The resistance took the credit for having defeated the Soviet Union, in that way contributing to ending the Cold War and bringing about the United States’ global hegemony.

Simultaneously, also in Peshawar, al-Qaeda was being formed. The end of the Cold War sowed the seeds of what would become known as the War on Terror. Once the ideological battle between communism and democracy was over, a religious conflict emerged in its place. We were there in the midst of this transition. At the American Club, we celebrated the fall of the Soviet Union and the victory of the mujahedin. Five hundred metres down the road, there was a meeting of the future leaders of al-Qaeda. I didn’t see it at the time. But do you have any reflections on this radical shift in global politics?

We found ourselves at a unique observation point. Afghanistan was one of the places where the so-called ‘Cold’ War was hot. The Cold War was being fought out there through armed conflict in a proxy war between Afghan communists, supported by a large number of Soviet soldiers, and the Afghan resistance movement, with support from Saudi Arabia, the United States and others. With the end of the Cold War, the communists’ power base eroded because supplies from the Soviet Union dried up. So the roots of this radical, violent Islamism lie further back in time – we can trace them far back in the Afghan context. But the Islamists first really got the wind in their sails when the United States and its allies wanted to build up the Afghan resistance to the Soviet Union. In that regard, Pakistan also had a finger in the pie. The Afghan resistance movement became so very radically Islamist quite simply because other political representatives of the Afghan people got neither recognition or support from Pakistan, the Middle East and the United States. They didn’t even get permission to operate on Pakistani soil, unlike the Islamist resistance groups.

In that respect, we need to go back to 1979–1980 to understand the change you’re talking about. At that time, the reality was that an Afghan refugee, who crossed the border to Pakistan and wanted access to humanitarian assistance, had first to join a political party. People who arrived at the Pakistani refugee commissioner’s office without a party membership card were turned away. Very few could afford this, so this mechanism was very brutal. These parties won great influence in the resistance movement throughout the 1980s and stood ready to intervene and take leadership when the Communist Party collapsed in 1992. In that regard, the end of the Cold War had a special twist in the case of Afghanistan. I remember very well an Afghan I talked to a lot about politics. He said that now we should just dread what’s coming, because during the Cold War, we could play off one superpower against another. Now we’ll end up in the shadows, he said, so now it’s really time to be sorry for us Afghans. I didn’t see it then, but subsequently I’ve thought a lot about what he said.

Some of the Islamists who lived around us later travelled to Tajikistan and participated in the conflict there. Later, they were in Bosnia, then Iraq. In fact, the international fighters who had come to fight against Communism and atheism became al-Qaeda, and later the same type of ideology led to the founding of Islamic State. I’m not saying that Afghanistan is necessarily at the centre of this, but many threads lead from Afghanistan to the major conflicts we have seen in the 21st century.

Well yes, but the ‘foreign fighters’ – to use a term that emerged only later – were really insignificant parasites during the war in Afghanistan. They didn’t do much of importance. Admittedly, they added some resources in the form of money and weapons and sympathy from rich donors in the Gulf, but beyond that they contributed little to the armed campaign. But for the fighters themselves, Afghanistan took on great significance. The mountainous country became a laboratory, a training camp, an opportunity to gain battle experience and to build a reputation as fearless warriors. There weren’t many Afghans who believed in this reputation, because of course they saw how little benefit they gained from the foreign fighters. But around the world, not least in the Gulf, it worked well. It’s difficult to imagine that international Islamism would be where it is today if it hadn’t been for the foreign fighters in Afghanistan. And it’s strange thinking about it now, given that at the time they seemed so insignificant.

Perhaps they were also inspired by having contributed to the fall of the Soviet Union? Perhaps that gave them hope that they could also overthrow other regimes by military means?

Yes, of course that’s completely correct. Even though it’s a myth that it was the resistance movement that defeated the Communists. When rebels are victorious and take power, they create a narrative about how they fought their way to victory. In reality, the war in Afghanistan was only one of many causes of the collapse of the Soviet Union. And the regime of Najibullah (Afghan president 1986–1992) survived the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and was still intact when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. It was only thereafter that the Afghan regime imploded. The contacts that certain individuals in the resistance movement had with people within the regime made it possible for them to engineer a split within the government and its security forces, so that the various military units joined up with different resistance groups. Accordingly, these resistance groups experienced a sharp increase in capacity. But those who had fought for the Communist government didn’t disappear, of course – you can still come across them 30 years later. Many of them have managed to adapt to different regimes, and have maintained varying degrees of visibility, but they have been survivors, and many of them have done pretty well out of their shifting loyalties.

What I learned from Afghanistan is that nothing is black or white, even though almost everyone wants to suggest that’s the case. Let’s stay with Afghanistan a little longer, and look at your research in more recent years, as well as your strong engagement in the public debate in Norway and your membership of the Afghanistan Commission [the Norwegian Commission of Inquiry on Norway’s civilian and military involvement in Afghanistan during the period 2001–2014] which was established by the government in November 2014 and delivered its report in June 2016.[i]

What was it that went so disastrously wrong? The parties in the Mujahedin movement from the 1980s gained power and then started fighting against each other. There was civil war. In the mid-1990s, the Taliban came in and took control of large areas of the country. Then came the attack on the United States on 11 September 2001 – the attack on the Pentagon and the Twin Towers. No Afghans were involved directly, but the response included an international military intervention in Afghanistan that removed the Taliban from power, and led to a new phase in the conflict that will soon have been going on for 20 years. What lessons can we learn from this? What could have been done differently?

Currently, one superpower, the United States, wants to withdraw. Russia is back. China has become involved. What does this mean for how we think about peacebuilding, about the opportunity that apparently arose in 2001 to create a new and democratic Afghanistan? Peace advocates whom you and I know well got involved in this; they were full of energy. What now? If the global community withdraws and, as in 1989, leaves the Afghans to themselves?

Pakistan is not present in Afghanistan for Afghanistan’s sake, even though this is what its rhetoric suggests. Pakistan is present primarily because of India. One of the biggest mistakes after 2001 […] was that India got to be a significant supporter of the Afghan government. That made Pakistan feel as though it was being trapped in a pincer manoeuvre, and that had consequences.

From a longer-term perspective, this is a civil war that began with the Afghan Communists’ coup d’état in 1978. The civil war became internationalized with the Soviet intervention over the Christmas period in 1979, and since then the war has been internationalized in various ways. It’s important to recognize that this is a complex conflict. The domestic political picture is complicated, with many actors and shifting alliances. It’s not a case of a constant conflict between two consistent parties. Alliances change the whole time on the basis of geographical identity, ethnic identity, religious identify, family acquaintance, friendships made between families and schoolfriends, and many other factors. The Afghanistan conflict is difficult to analyse.

In addition, it’s not only complex internally. It’s also very complex internationally. One thing is the superpower aspect of this, how for a long time Afghanistan was one of the Cold War’s hot spots. Another thing is what has happened subsequently, not least with 2001 and the American intervention in response to the terror attacks in New York and Washington. In addition, there is a complex regional picture, in which each of Afghanistan’s neighbours has its own role. I’ve done a lot of work on this, and my analysis deviates from the standard view.[ii]

I argue that the involvement of Afghanistan’s neighbours is not motivated primarily by an interest in Afghanistan itself. They get involved because they perceive threats to their own national security. Pakistan has been perhaps the least helpful of all of Afghanistan’s neighbours over the past 40 years. But Pakistan is not present in Afghanistan for Afghanistan’s sake, even though this is what its rhetoric suggests. Pakistan is present primarily because of India. One of the biggest mistakes after 2001 – you asked what it was that went wrong – was that India got to be a significant supporter of the Afghan government. That made Pakistan feel as though it was being trapped in a pincer manoeuvre, and that had consequences. A new proxy war commenced and has continued on Afghan soil over the past 20 years, this time between those supported by Pakistan and those supported by India. This is one element in the complexity of the Afghan conflict. Afghanistan could have sought a form of neutrality, but there has been little interest in pursuing that.

Those who say that they know a solution, and if this or that had been done differently, everything would have turned out well, have no credibility. No one can be completely certain what would have been best. It’s easy to say that much has gone wrong and could have been handled differently, but that wouldn’t necessarily have resulted in full peace and harmony.

For Afghanistan, it’s a huge paradox that during those periods when the window to a peaceful solution was open widest, the parties were least willing to take advantage of that window. Early in the 1980s, the Soviets realized that they had landed up in an undesirable conflict, but the United States and its allies – in particular the United States – saw it as expedient to conduct a proxy war against the Soviet Union on Afghan soil, and so did what they could to hinder dialogue. Something similar happened in 1986–87, when both the Communist regime in Kabul and Gorbachev’s Soviet government wanted to find a peaceful solution. This ended with an agreement, but it came too late. After 1992, when the Communist regime had fallen, the window was once again slightly ajar, but by then the rest of the world, with the exception of certain neighbouring countries, had completely lost interest in Afghanistan. The Afghans were left to their own devices. This is something that many have regretted subsequently.

For Afghanistan, it’s a huge paradox that during those periods when the window to a peaceful solution was open widest, the parties were least willing to take advantage of that window.

And perhaps the most important example of all was the period after 2001 when the Taliban were down and out and the movement almost collapsed. At that time, Taliban leaders expressed interest in, and willingness to engage in, dialogue, were minded to sign a binding peace treaty, and integrate themselves into Afghan policy, but they were rejected out of hand. Today, most influential international actors want a peace agreement, but now the local obstacles to achieving an agreement are probably greater than at any time since 2001. The tragic paradox of Afghanistan is that the better the opportunities for peace have been locally, the less international interest there has been in participating. And the greater the local obstacles have been, the greater has been the international interest in peaceful solutions.

Military Power or Dialogue

An important element in this paradox is of course that it was a weakened Taliban who were interested in negotiating. Now the Taliban are strong again, and in a position to dictate the terms for negotiation.

That’s correct. That’s one of the reasons why it’s now difficult to achieve peace. It’s obvious that some of the political views that the Taliban represent, and that they displayed during the time that they were Afghanistan’s de facto government (1996–2001), are unacceptable to large parts of the global community. Even if we believe, as I do, that dialogue is important, we cannot be certain that the Taliban are willing to share power with others and respect fundamental human rights, such as allowing women to participate in education, the labour market and politics. There are major, unresolved questions there that give very serious cause for concern.

With regard to the military aspect, we can no doubt conclude that a massive use of military force, including from Norway, has not brought about the desired result. It has neither defeated the Taliban nor created a basis for peace. Even so, it can’t explain the fact that the Taliban are back.

The Taliban’s success must have something to do with how the Afghan state is structured; on what has been emphasized, both politically and economically. There have never been so many Afghans living in poverty as today, despite the billions [of dollars] that have poured in. There has never been as little support for the Afghan government as today, despite all the measures that have been put in place to get it to function. From a peacebuilding perspective, is it individual elements, or is it the sum total of what has been done, that is wrong? What have we learned?

There was a period when we talked about Afghanistan in the context of peacebuilding. No one does that today. Nowadays, it’s usual simply to affirm that Afghanistan has lived with war for 40 years, and forget that there was a period when we talked about building peace. It’s striking how the Taliban could collapse in 2001 like a house of cards. Many of those who had served on the Taliban’s front line returned to their mosques or madrassas, or to their farms or shops, and adapted back to ordinary life. They were anticipating a completely different future. But in the course of just two or three years, the Taliban began to rebuild their network, to present a military challenge to the international forces and the government. I think there were two factors that contributed to this.

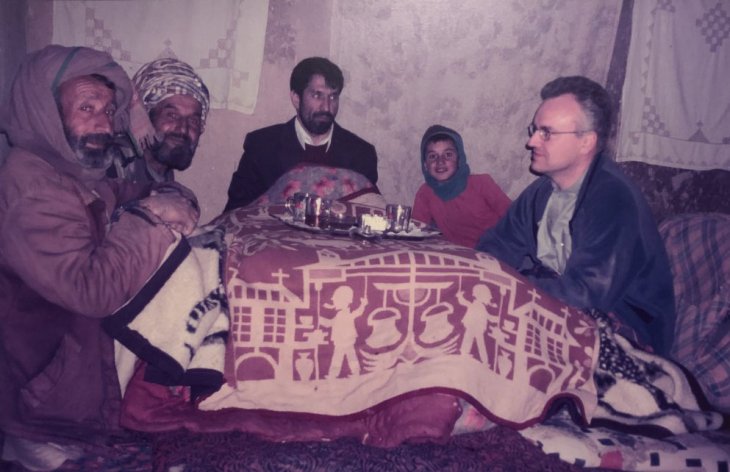

Kristian conducting an interview in a village outside Herat, Afghanistan, December 2002. Photo: Private archives

One was that the people who were appointed to important positions in the country, not least to leadership positions locally, had little legitimacy. They were former commanders, former warlords. They were well known. If there was one thing that Afghans knew, it was what these people stood for. Many Afghans would no doubt have said that although they had little sympathy for the Taliban, there was one thing the Taliban had done that they saw as valuable, and that was that they had got rid of precisely these people. But then the international community turned up and reinstated them. It was almost as though the world was vacuumed for former warlords who could go and fight against the Taliban during the intervention in 2001. We brought them back after they had won the war for ‘us’. When I say ‘we’, I’m not implying that I supported that war, because it wasn’t something I wanted. These warlords were generously rewarded with attractive and powerful positions in the new structure of government. Locally, there were many people who objected to this. Obviously, to a large extent, this was also about local conflicts: regardless of whom you install in a governmental structure locally in Afghanistan, there will be some history of conflict between them and others. In any event, it motivated people to look for an alternative, and the only available alternative at that time was the Taliban, who were in the market to begin to recruit and rebuild their organization.

One factor that I think was equally important was the internationally run military campaign. In autumn 2001, there were few international soldiers; in fact, there were no soldiers, only some intelligence agents, military advisers and air controllers [identifying targets and directing aerial attacks] and that kind of thing in the intervention phase. But soon afterwards, a number of international soldiers arrived, who worked with Afghan militia groups and the Afghan army, and they carried out this work in a way that took many lives, trampled on people’s rights and destroyed people’s harvests and infrastructure. These soldiers generally conducted themselves in a way that was widely seen as completely unacceptable. And once again, the people had only one alternative when it came to seeking protection, and that was to turn to the Taliban, who were slowly rebuilding their organization. In that way, the Taliban got the wind in their sails.

If you take away those two factors, it’s impossible to explain the resurgence of the Taliban. Because even in their heartlands, the Taliban were not a very popular organization in 2001. There had been many uprisings, protests against the forced conscription of young boys to their forces, the use of force to collect taxes, and that type of thing. It wasn’t inevitable that the Taliban would manage to rebuild, they had to have help to achieve that. And they obtained that help from the unfortunate decisions that were taken following the international intervention.

The Afghanistan Commission

Norway is one of the few countries that attempted to conduct a critical review, by establishing the Afghanistan Commission in 2014, of which you were a member. The conclusion was that the only positive result of Norway’s many years of engagement in Afghanistan was that Norway got to demonstrate its reliability as a NATO ally.[iii] The Commission’s report was extremely critical.

What was it like to be involved in that process? Internal discussions are one thing, but it’s a different thing to defend the findings in public afterwards. Am I right to think you didn’t get much opposition? All the same, it was a brave move; many countries have just wanted to forget, avoided any discussion of their own roles, and just continued to provide aid. You are a researcher with a strong empirical background, concerned with opportunities for peace. Was it challenging?

What was it like to meet Norwegian politicians and tell them that what they’d done over the past 14 years had scarcely resulted in anything positive, and that you could document this fact?

It was extremely interesting work with very able people on the Commission and in the secretariat, and the work gave me the opportunity to meet all the key decision-makers in Norway. We also interviewed international decision-makers. We got to ask how they had viewed the developments, what they had thought, what was the basis for their thinking, and what decisions they had made. Obviously this was incredibly interesting, especially for someone who had followed events in Afghanistan so closely. I also saw that the Commission’s conclusions, although they were rather critical, were largely perceived as an accurate summary of Norway’s role in Afghanistan. Yes, they are harsh conclusions, which deviate sharply from the official justifications supplied in advance of, and during, the involvement in Afghanistan.

I remember an article in [the Norwegian newspaper] Aftenposten [1 November 2007] written by the leaders of the three parties in the red-green coalition government: the Labour Party, the Centre Party, and the Socialist Left Party.[iv] What I realized afterwards was that in that article, they tried to consolidate a kind of joint position, despite their strong disagreements. In that article, not a single word was devoted to the importance of Norwegian participation for Norway’s alliance with the United States and NATO. So when we came later, and said that that concern for the alliance was probably the most important reason for Norway’s engagement in Afghanistan, and that the preservation of the alliance was the only thing that Norway was successful in achieving, our statement stood in stark contrast to the types of justifications that the three party leaders had supplied in Aftenposten.

Minefields – Work to Impact Policy and Practice

I’m sure we won’t succeed in leaving the topic of Afghanistan altogether, but now I’d like to move further along in your research career. Of course this grew out of your work in Afghanistan, and also came to encompass the problem of landmines, among other things.

Yes, it grew from the fact that I’d worked in Afghanistan. In the 1990s, when I returned to Norway, I started working towards an M.Phil. In my dissertation, I wrote about political mobilization among Afghanistan’s Hazara people, an ethnic minority, which also to a large extent is a religious minority, because most Hazaras are Shia Muslims, unlike other ethnic groups in Afghanistan, who are Sunni Muslims.[v] The Hazaras went through a dramatic period politically throughout the 1980s, with various forces that ideologically and in other ways pulled in different directions. I thought this was an exciting topic to work on. In a sense, this was a study of non-governmental military groups: how they build themselves up and how they justify their activities, and recruit, and organize themselves and behave in conflict. This is an interest that I’ve continued to pursue, for example in my study of the Taliban.

The landmine issue re-emerged as a political problem just at the time we were both working there in the late 1980s and the early 1990s. People saw the enormous human consequences of the landmines and started mine-clearing measures, rather helplessly in the beginning. Some of the people involved became influential in what from 1992 onwards became the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), which in 1997 secured an international treaty banning landmines, and was even awarded the Nobel Peace Prize the same year. This was something that captured the interest of a retrained, practically-oriented farmer, both politically and practically. At one point, I went to Afghanistan with a colleague to take part in a mine-clearance course. I wanted to learn the techniques, and there was a lot to learn. But to start with, I was most interested in the political aspects, in the idea of landmines as an ethically unacceptable weapon.

Undergoing mine clearance training hosted by the Monitoring, Evaluation and Training Agency, Jalalabad 2001. Photo: Private archives

There was more value for money in clearing three landmines buried around a village water hole than in clearing a large, fenced-off minefield in an area where hardly anyone dared venture anyway.

The unique thing here was that we gradually developed a broad alliance of anti-war activists, retired soldiers, politicians, humanitarian organizations and mine-clearance organizations, who stood together and pursued this campaign and to a large extent were successful. When negotiations on the Mine Ban Treaty were completed in 1997, not all countries were ready to sign. The superpowers, and several other important countries, such as Israel, India and Pakistan, have still not done so. But the reality was that the Treaty was complied with. For a long time, hardly any new landmines were deployed. Now, the situation is different. In a number of conflicts, landmines are again being used on a significant scale. In the long period after 1997 when landmines weren’t used, I became interested in mine clearance, how one went about that work. I realized that large-scale resources were being used to clear the largest possible areas, and remove as many mines as possible, without any prior assessment of what was most important for the people living there. In brief, it was about finding a mechanism for establishing priorities. There was more value for money in clearing three landmines buried around a village water hole than in clearing a large, fenced-off minefield in an area where hardly anyone dared venture anyway.

Let us take this as an example of two things: a collaboration between researchers, activists and politicians who actually achieved something, and the independence of research. Independent research led to change in how the actual work of mine clearance was conducted. You contributed both to achieving a ban on mines and to addressing the problem in the most economically efficient way for the people who were really affected.

This is a brilliant example, I think, of how a collaboration between critical research, critical activists and politicians can lead to positive change. Not just politically, but also in the way of approaching a problem. Here, we see how a researcher can make a contribution to peace.

Obviously, the researchers had to deal with the political authorities. The first thing to say about that is that many of the most important agents for change were found within various countries’ civil administrations, and not necessarily in activist communities. If it hadn’t been for a number of pioneers, including in the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, there would never have been a Mine Ban Treaty. The activists also drew a lot on research and also conducted some research themselves. Some of it was pretty good, while some was less rigorous. It was a challenge that people tended to throw around numbers – the number of mines in the world, how many people were killed by mines, and so on – that lacked any empirical basis. After the Mine Ban Treaty was signed, these numbers came back to haunt them. They had established such an enormous estimate for the size of the mine problem that it would have been impossible to solve. And so there was no real reason to try to do anything. One had to downscale the estimates in order to get rid of the mines. Now some realistic estimates were needed, not the activist estimates that had motivated political action. It was an interesting turnaround.

And then we also worked closely with the mine clearance organizations. They found much of their expertise among people with military backgrounds. They had organizational cultures that differed from both those of the activist community and those of the rest of the aid community. Mine clearance is a risky activity. It requires discipline and thorough organization. We now challenged these organizations on how they fixed their priorities, showing that in practice, the consequences of not conducting a socio-economic analysis in advance of a clearance operation could result in a rich local landowner benefiting at the expense of the poor, without the organization even realizing it. And yes, not everyone was equally happy to have this pointed out. We had some difficult discussions. But we worked and conducted dialogues with the various organizations, carried out field studies on the projects they themselves were implementing, and also worked in a climate where there were others who were also working towards the same goal.

And then a fundamental change took place in the way people thought about mine clearance. Now there was more dialogue with the local population and a larger number of rigorous socio-economic analyses, and the operations were followed up and evaluated, both as they were underway and in the first few years after completion. This made it possible to avoid taking measures that as a starting point were based on the best of intentions, but in fact had major negative consequences.

And so does peacebuilding, the types of elements it may involve, then come into the discussion?

Absolutely. Something we were interested in was how mine clearance could contribute to peacebuilding. One thing is that mine clearance makes it possible for people to start working again, to cultivate the soil and drive on the roads, to move back to rural settlements. And that in itself in a way helps to bring about peace. In addition, one can also organize mine clearance measures in a way that builds bridges between groups that have been in conflict: one can recruit mine-clearance operatives from several population groups; one can recruit people from what was an occupying power to clear mines they laid themselves, in a gesture of reconciliation. There are many ways one can envisage building peace as an extension of mine-clearance measures, and we worked on that intensively for a period at the end of the 1990s and a little into the 2000s. I felt that we got support for our ideas. It’s been good to see that some of the work we did then has been taken up later, for example in the peace process in Colombia, where there has been a very strategic use of mine-clearance measures as a contribution to reconciliation and peacebuilding.

Research into Migration

I also see a connection with another field in which you have built your research career, that of migration. I’ve always seen PRIO as one of the leading centres for research into migration. You were a part of that. Can you tell me a bit about it, before we touch on your leadership roles at several levels in PRIO?

What was it that made PRIO so good at research into migration? Was it because of a strong theoretical basis, or because people had extremely good field experience, or because of the way it was organized? Is there something we should learn from here?

I’m not going to take much credit for research into migration being a strong area at PRIO. It obviously has a lot to do with a number of individuals who were both able scholars and creative when it came to method, theory and data gathering. I think those were the main factors. In addition, I think that at PRIO we have been good at creating a workplace that provides a stimulating environment. It lets its researchers discover their strengths, and carve out their own place within the organization. And then it has something to do with the fact that migration itself – not just directly conflict-related migration in the form of surges of refugees and internally displaced people, but also other types of migration – is often closely related to conflict. The large scholarly community at PRIO that studies conflict and peace has, I believe, contributed to the development of research into migration.

In this respect, I am somewhat critical about migration as a distinct field of research. Research into migration has become a research topic in its own right, almost a separate discipline. Migration forms a part of many social changes. If we look at change processes in Norway today, and subtract how people relocate because that’s a separate research discipline, then we won’t understand much about what’s going on. We don’t understand so much about the politics either, we don’t understand so much about local conflicts. And there I’m thinking not only of international migration, but just as much about internal migration. If people move from Otta to Oslo, it affects the age structure, the sex ratio, and business development. I think the context of research into peace and conflict has been of great importance for the development of a broad-based environment for research into migration at PRIO.

You have also ended up in the midst of debates about immigration to Norway, and not only in relation to the themes you just outlined.

Well yes, and there’s been internal debate within PRIO about that. Traditionally, PRIO has focused on international conflicts, and has avoided research into situations that are purely Norwegian. But then we have come to realize that many conflict-related factors do not follow national borders. If you’re going to work on war and peace, you have to liberate yourself from the system of nation states. And if you don’t liberate yourself completely, you must at least look across the system of states and national borders. Migrants are often important actors in the regions and countries that they come from. For someone studying the Afghan conflict, it may be necessary to keep track of what is happening among the exile communities in Norway, Germany and the Netherlands. We have become more and more interested in transnational considerations and networks.

One finding in PRIO’s research that has gained a lot of attention is that – quite contrary to the general assumption that immigrants are concerned about their homelands and spend a lot of time there, and are poorly integrated into the country they have relocated to – these immigrants often have the resources necessary to be active in both countries. In other words, there is no contradiction between being active in the area you come from and being well integrated in the country you have come to. In fact, there’s a synergy. Research into migration has contributed to a good deal of myth-busting by not only looking at the countries that migrants come from, but at the networks that bind people together over borders and great distances.

I question this idea of the so-called ‘refugee crisis’. It’s true that there was a dramatic increase in the number of refugees coming to Europe, but we are talking about slightly over one million refugees arriving in a continent with over 500 million inhabitants. Calling this a crisis rings hollow when you have situations like the one in Lebanon, where one million refugees arrived in a country with five million inhabitants.

I think the debate in Norway has been one-sidedly focused on rights. ‘They mustn’t be given rights! They must be sent back. There’s a duty to send back those who don’t fulfil our criteria!’ In contrast to the landmine debate, this debate has become extremely politicized. Strong emotions come into play. Supporters of immigration clash with anti-immigration voices in the Norwegian debate. It’s a difficult debate to get involved in.

It’s a difficult and sometimes ugly debate. Many of PRIO’s migration researchers have found it unpleasant to take part in it, not least when they encounter posts on closed forums on social media, which can be unpleasant, bullying, and sometimes threatening. And it’s correct that the debate on migration has changed a great deal. It’s clear that until 2015, many migration activists were saying that we must open our borders. I don’t think I’ve heard anyone say that since 2015. That viewpoint has died out completely. Now, even the most ardent activists will say that we should respect our international obligations to a greater degree, and ensure that people who are in real need of protection have the opportunity to get it. Today, this moderate view has become the most radical position. The debate on migration is difficult and very polarized.

In my opinion, it is also about many other conflicts. We see that people justify their opposition to migration in many different ways, and I think many of us have made a bit of a mistake in thinking that opposition comes mainly from the far right. There is strong opposition to migration, supported by different arguments, across the whole political spectrum, among trade unions, on the left, in rural communities, in the Centre Party. In many other countries, fear of migrants is apparent also among Christian democrats and conservative Christian communities. There are various types of reasons, but opposition to migration resonates in almost all types of ideological landscapes in Europe. This is cause for great concern, because it can clear a path for unconventional alliances that could become powerful. The world is fundamentally unfair, we all know that. At least in the short term, it is unrealistic to envisage an end to the system of nation states.

Of course, it’s easy to enter into a purely theoretical debate about the integration of refugees, but when the reality was suddenly that thousands and thousands were coming into Europe, after Turkey had opened its border, the debate became completely different.

That’s definitely correct. I question this idea of the so-called ‘refugee crisis’. It’s true that there was a dramatic increase in the number of refugees coming to Europe, but we are talking about slightly over one million refugees arriving in a continent with over 500 million inhabitants. Calling this a crisis rings hollow when you have situations like the one in Lebanon, where one million refugees arrived in a country with five million inhabitants. When the surge of refugees was perceived as a ‘crisis’, rather than as a challenge that Europe should tackle by working together, it was because a general scepticism about immigration had grown so strong that it was possible to use that scepticism to gain political support for that perception.

We saw this most clearly in the most migration-friendly European countries, Germany and Sweden, where the authorities made complete U-turns. It’s easy to forget now, but when Sweden’s conservative prime minister Fredrik Reinfeldt spoke about it as an opportunity to ‘open our hearts’, there was no suggestion that Sweden should close its borders. That was completely out of the question. His party campaigned for election on this basis and suffered huge losses.

In fact, more Afghans returned to Afghanistan in 2001–2002 than came to Europe later. Is there anything that researchers can contribute in these types of contexts?

Many participants in the public debate are not very receptive to what I would call facts, to hard, factual information. Obviously, that’s disappointing for us researchers. But researchers must also be careful that they don’t take on a purely activist role. That is the other trap that one may fall into if one gets too frustrated about the public debate. I think that we researchers have to come to terms with the fact that we do not have political power. We have a lot to contribute to these debates, but the results are seldom a carbon copy of what we suggest or support. And it’s also not our role to determine policy. Our role is to enlighten politicians and inform the public debate. Once we realize this, I think our influence becomes greater than if we take on an activist role.

Yes, perhaps over time, but perhaps not when the topic is one that researchers are passionate about and believe that they have knowledge about there and then…

I think that we researchers have to come to terms with the fact that we do not have political power. […] it’s also not our role to determine policy. Our role is to enlighten politicians and inform the public debate. Once we realize this, I think our influence becomes greater than if we take on an activist role.

The PRIO Director

We’ve talked about your varied background, with research that contributed to changes in international policy and practices in the area of international aid. We’ve talked about research into migration and how the field has developed. As a researcher, you’ve had a two-track career. The whole time, you’ve been involved in both research and administration.

You were Research Director at PRIO when we worked together there, then later you became Deputy Director. And, in 2009, you decided to apply for the job of Director. Why did you do that? You weren’t a conventional theoretically-oriented researcher, but someone who combined theory and practice. What ambitions did you have when you took on that responsibility?

Just working at PRIO was a dream in itself. When I was doing my M.Phil. in sociology at the University of Oslo, I wrote my dissertation on a student fellowship from PRIO. So when I got a job there in 1995, it was a dream come true. And then I got new contracts and new opportunities, and as time went on, I became Research Director. But I wasn’t really looking for a career in research management, it was research itself that I was passionate about. However, when I was asked to take on management roles, first as Research Director, then Departmental Director and then Deputy Director, I found that doing the organizational work was enjoyable, that it was fun getting things to function. That no doubt had quite a lot to do with my background. Even so, it was only after the position of Director had been advertised that I began to think of myself as a possible candidate. I really haven’t thought about it before. That might sound a bit strange, because by then I’d already been Deputy Director for nearly four years. But that’s how it was. And once I began thinking about it, I realized it was something I wanted to do.

Kristian with his daughter, Anna, at PRIO’s offices in Fuglehauggata, 1995. Photo: Victoria Ingrid Einagel

Also, I believed I had something to contribute. For me, it was about the fact that I find leadership and organization enjoyable, and that it’s particularly enjoyable to head an organization that does something important. The job of director at PRIO became a leadership role that I was passionate about. I think I also had some advantages: one was that I felt I had good relationships with everyone working at PRIO. I didn’t have any likes or dislikes. That’s a clear advantage if you’re going to head an organization where you’ve already been working a long time.

And so what was it that I wanted to achieve? I was very well aware that I – to use a Norwegian expression – was jumping after Wirkola [a Norwegian expression that basically means ‘I had a hard act to follow’].[vi] In other words, I was taking over an organization that was well run, that was perceived as one of the best academic institutions in Norway, and that had a strong international reputation. There’s no one who works on peace and conflict who isn’t aware of PRIO. That meant I didn’t have any ambitions to be a revolutionary, to tear things down in order to build them up again. It was more about preserving the good qualities that PRIO already possessed and developing them further. I realize, of course, that this process of further development requires a rather high level of commitment. It’s one thing to preserve the good qualities, to recreate them every day; that’s not something that happens of its own accord. It’s easy to think that one just needs to stand still, but that view is fundamentally flawed. In order to preserve the good qualities, one has to engage in constant renewal. It’s about generating new ideas, it’s about employing new people, finding new ways of doing things, ensuring that the organization receives continual injections of new energy and enthusiasm, so that people have the desire to create something.

And at the same time, there’s the additional factor that you’re operating within changing external conditions. And so you have to adapt and find opportunities in these changed conditions and create something new. There’s no doubt that PRIO has changed a lot over the past decade and has become a more professional organization. This applies to leadership, on which we’ve placed a lot of emphasis, to training, to systemization, routines, and recruitment, both in general and at a senior level. It’s about research communication. And it’s about administration in general, everything from financial management to human relations. It’s about research administration specifically. In that respect, I’m thinking in particular about improving funding applications and the implementation of research projects. These areas have become very much more demanding, with more criteria that have to be fulfilled, and more intense competition. Nowadays, there’s a larger number of powerfully competitive institutions than was the case 10 years ago. And this also applies to a number of other things, such as security and preparedness routines, that we have made much more professional. So it’s clear that PRIO today is a more professional and better structured organization. That’s been almost essential; there has been a conscious organizational shift that we have all engaged in together.

Research Dissemination

Is it possible to generate academic knowledge, assure its quality, publish the results in reputable journals, and disseminate knowledge to those who may benefit from it either practically or politically – all at the same time?

We’ve done a lot of work to improve our communication skills. The way we think about dissemination has become engrained in the organization, and for good reasons. Traditionally, researchers, also at PRIO, would think mainly of writing research articles, books and book chapters as an integral part of their research. To generate new knowledge, and make it known to fellow academics, is fundamental to everything we do. But it is equally important to communicate this new knowledge to other audiences. In my experience, reaching out to other audiences is often also a key to having a greater impact on academic audiences. In addition to academics and the general public, we must also target a more specialized audience, namely the policymakers and stakeholders who might use our knowledge for developing new policies or holding on to successful ones. To reach them, we need different tools. We have innumerable tools at our disposal.

When we find ourselves sitting on an interesting research finding, we should identify the most effective channels for reaching the relevant audiences. Ideally, all research projects should have tools that reach all three types of audience: academia, the general public, and practitioners. But we can’t do everything all the time, so we have to make informed choices. Ultimately, it is about what I would call musicality. In other words, the ability and willingness to keep track of the ongoing social debate, to keep track of ongoing processes. Where will it be possible to plug in this knowledge? Who will be receptive to it? You may have the world’s most interesting research finding, but if your timing is wrong, or if you don’t see where you should plug it in, it will never get further than your desk drawer or your computer.

This is a subsidiary question, but to what extent did it become your job to disseminate research findings when you were director of PRIO? As someone who was often called up by the media, could you use your position to disseminate results from your colleagues’ research projects?

How does one generate a unified understanding of the many elements that are produced within an institution such as PRIO? Are there mechanisms for achieving this?

As director, one has both one’s own research and that of others to use as the basis for dissemination. It’s obvious that one will be more secure, more competent, within one’s own research portfolio. And one should participate in the debate oneself. When it comes to research by other people, it’s more complicated. Often, it’s the person in charge who is invited to comment, even though he or she is not the one with the most knowledge about the topic in question. There are good reasons for instead asking the researcher who has actually done the research to present it.

Kristian in the studio for an interview on NRK P1 radio. Photo: © Signe Margrethe Dons

There has to be scope for both approaches, but it’s clear that in the main fields where PRIO has engaged in systematic research over long periods of time, such as the study of trends in peace and conflict, it’s important that the director is able to present it, to promote PRIO’s brand and set external footprints. But one must present it with full respect for, and acknowledgment of, the people who have done the work. In general, this is a win-win situation, because the people who have done the work are also interested in seeing their work made visible.

Gender Distribution and Leadership

I have great respect for the gender-related research advanced by PRIO. PRIO has not yet had a female director, but there have been many visible women within the organization who have been at the forefront of the debate about gender, peace and conflict. Indeed, this is an example of the balance you talked about, whereby you promote those who have expertise and they are granted permission to grow within their role. Is that how it is?

The fact that PRIO has not yet had a female director, apart from a brief period when Hilde Henriksen Waage filled the role during her term as deputy director, is nothing to be proud of. In fact, it is also not long since PRIO promoted its first woman to a research professorship.

I think it’s slightly strange that such a strong scholarly environment has not hired a woman as director, either from its own ranks or from the outside.

That’s true, but over a 10-year period, we have gone from having an extremely lopsided gender distribution at the senior level to a situation that is completely and utterly different. When I say senior level, I’m thinking both of women in leadership positions and women who rank as professors. Some of it has to do with demographics: a new generation has emerged whose members have struggled their way up, completed their doctorates, worked hard, and been strongly engaged in their work. It’s also about a deliberate policy to promote the careers of women in peace research.

Photo: Used with kind permission from Killian Munch

Framework Conditions and Organizational Culture

This leads me to ask about PRIO’s financial structure and research funding. How much scope is there for strategic interventions? Even though PRIO has core funding, the Institute is locked into three-to-five-year funding cycles for its research projects. At the same time, one must be constantly ready for action and taking up new issues and ideas.

There is scope to be strategic, but it is far too restricted. PRIO has core funding that corresponds to around 15–17% of its total budget. To a large extent, this is tied up in the costs of research management and drafting new project-funding applications, and it provides inadequate scope for pursuing new ideas. In reality, this means that when someone at PRIO gets a good idea, or wants to build up her or his expertise about a new topic on the horizon, the Institute is not able to allocate much in the way of resources until it has obtained external funding. And these external funding cycles operate slowly. It might take one, two, three, or even four years to get the funding. But by then, the ship has sailed, you’re too late.

From this point of view, I think our strategic room for manoeuvre is inadequate. Our core funding should correspond to about a third of our turnover. That would be ideal. I wouldn’t ask for more than that, because it’s healthy to exist in a market and compete for external funding. Research is not like an ordinary business activity, however. It needs a lot of long-term planning. Accordingly, our core funding is far too small. When the financial room for manoeuvre is so restricted, it makes the institution dependent on the commitment and initiative of individuals. New research initiatives cannot be set in motion from above. I would have liked to have seen the Institute get greater opportunities to control its research agenda, set priorities, take up new ideas and new topics.

If you think about the whole spectrum of activities that you engaged in as director – structural change, funding, organization, communication, research policy, and public debate – what would you wish to highlight as your most important achievement? You were active in many arenas and were highly visible in the public debate, both in Norway and internationally.

It’s difficult to say that it was my achievement, because it was all about teamwork, but I think the professionalization of PRIO as an organization is something to be proud of. We talked a bit about communication and how we think about communication. In that connection, we’ve changed direction towards what I’d call an integrated approach to research communication. Instead of thinking that in my role as a researcher I have an obligation to communicate with other researchers, and perhaps to some extent to communicate with other audiences when I feel like it, we have now adopted a rounded approach so that we communicate constantly with a range of audiences, and these activities are integral to our project development and implementation. I really believe that we have developed an approach that makes a difference, that increases our visibility and, not least, our ability to reach those audiences we should be reaching. We have also become better at arguing that our projects are worth funding. We have put in place a way of thinking about communication that is fundamentally strategic.

Does this also mean that the organizational culture is one in which the researchers themselves are eager to communicate their research and get involved? That’s the impression I get. I think that PRIO has an extremely competent communications department that is capable of motivating researchers and improving the products they produce.

Yes, the most important thing is the actual organizational culture. Just creating good-looking diagrams and documents has little value in itself. The key thing is for the communications to be anchored in the organization and its research. The entire organization has contributed to developing the system we now have at our disposal. In addition, our support functions are focused on change: on working on strategy; and proposing communications strategies for specific projects and initiatives. The primary function of the communications department isn’t to work on individual products.

The Development of Peace Research and the Challenges It Faces

Let’s turn now to the field known as ‘peace research’. You were Director of PRIO for eight years and you have been involved with the organization for a long time. PRIO has a central role in international peace research. But what have been the major changes during your time? Is it correct that peace research has moved from having close links with peace activism towards engaging in critical reflection on that activism?

Has peace research moved from being anti-military towards engaging in dialogue with military circles? What are the most important changes? I’m asking about this, because afterwards I want to ask you about how we should think about making positive changes to our world today, where a lot of things are not going particularly well.

Peace research has developed in several different phases, and I don’t think that I’ve made my analysis sufficiently detailed that I could sit down right now and write an article about your question here and now. But very broadly, I would say that if we go back to the 1970s or 80s, it was usual for PRIO and other peace research environments to be seen as institutional participants in international peace activism. Peace researchers did not have strategies that were purely research-based, but they engaged themselves in issues where they hoped they would be able to promote change – in disarmament, for example. Peace research represented an aspect of the anti-war activism that emerged in the wake of World War II and which reached its peak during the Cold War, not least after NATO’s Double-Track Decision in 1979, which was when I decided to refuse to attend my military refresher training.

After the end of the Cold War, the fronts changed. There was scope for communication and alliances between groups that had not previously been on speaking terms. As you mentioned in one of your earlier questions, peace researchers began to conduct dialogues with military decision-makers about security policy. They began to discuss military strategy and military ethics (jus ad bellum and jus in bello) – questions that peace researchers had not touched with a bargepole previously. There were a lot of sour faces in activist communities because of this, but it was necessary for peace research and for maintaining its relevance. If we go a little further forward in time, particularly to the War on Terror after 2001, we see a dramatic shift in thinking about war and peace and the use of military means. The use of military force internationally, as a means to manage, damp down, and prevent conflict became acceptable, at least if a UN mandate was in place.

There was also another shift, perhaps not as early as 2001, although the seeds of it were already there at that time. This was a shift from focusing on conflict resolution and the laying of the foundations for lasting peace, to being content with a lower level of ambition, mainly managing conflicts to ensure that they did not spin out of control and have major negative consequences. Much of the international involvement we are seeing today in Libya, Mali and other places does not aim to create lasting peace. The goal is simply to keep the problems at a level where their effects will not be too damaging – at least not for the outside world. This is something that peace research must come to terms with: we find ourselves in a different political climate and have taken on a role that is perhaps more defensive.

For you and me, Afghanistan is perhaps the most striking example of this trend, but the same applies to Iraq, Syria and Yemen. And there is hardly anyone today who believes it is possible to make peace between Israel and the Palestinians. The political will, and the belief that one can go from war to lasting peace, have been weakened. At the same time, quantitative research has contributed to raising awareness about how much more peaceful the world is today than it was during the two world wars and the Cold War. Although things have gone in the wrong direction over the past decade, we know that we have a lot to lose. Accordingly, it’s important to maintain the multilateral cooperation that was built up after World War II, to avoid further terminations of disarmament agreements, and to avoid a new Cold War – this time between the United States and China.

It’s important to maintain the multilateral cooperation that was built up after World War II, to avoid further terminations of disarmament agreements, and to avoid a new Cold War – this time between the United States and China.

And there’s also another area where I think that we peace researchers have an important defensive role to play. That is to defend scholarly research. If we fast-forward to today, peace research – well, actually all research – faces a challenge that has become more and more obvious over recent years. This is that powerful political forces do not respect the core values that serve as the foundation for research: namely, the obligation to seek the truth and to build logical and consistent arguments. Opponents of scholarly research are gradually emerging in all sorts of media. The United States is led by a president who permits himself to misquote a research report one minute, and then say the complete opposite the next, without losing any support from his voters. Sometimes I feel as though we have a debate in which the value of research has become purely decorative. People continue to use research and its status to give weight to their own arguments, but they neither understand nor respect the basic research value that is the value of truth.

Director of the PRIO Middle East Centre Kristian Berg Harpviken at the event ‘Preserving Spaces for Dialogue in the Middle East’, Jordan, 3 March 2020. Photo: Indigo Trigg-Hauger / PRIO

The misuse of research is an attack on research in general, and these attacks come from politicians fulfilling leadership roles in some of the world’s most powerful countries. There are politicians who would prefer not to have strong, independent research communities and who have many instruments at their disposal for undermining independent research: everything from discrediting serious researchers in the public media to removing funding; or prosecuting academics who produce findings or interpret data in ways these politicians do not like. This situation is troubling. I’m not sure how we as researchers should deal with it. I believe that an important starting point is to avoid falling into the trap of starting to argue like the most tendentious politicians: we should not be too activistic; we must avoid inaccuracy both with statistics and other facts; we must insist on the value of truth, even when this is uncomfortable. If we fail to do these things, we will lose our basis for meaningful communication.

This means that we must ask disagreeable questions and report disagreeable findings, including those that we ourselves find disagreeable. If we find, while conducting research into migration, that in certain situations a particular type of migration promotes conflict, then we must be willing to say it – even if we don’t like it. Researchers must reflect on their own role and their own practices, and strengthen their adherence to scholarly values.

Is there now less explicit peace research because areas that were traditionally seen as peace research have become integrated into other fields and scholarly disciplines? Has there been a shift in the whole focus and understanding of peace and conflict research, a move away from its earlier themes?

Yes, what many people think of as peace research’s crisis is actually its success. If we go back 30 or 40 years, peace research was a peripheral activity conducted by a tiny group of researchers. Today, peace and conflict research is central in a number of disciplines and also in interdisciplinary research. In the study of international relations, and partly also in political science, we see that themes from peace research often dominate. But as you said earlier, this type of theme, a broader understanding of war and peace, is important in a range of research fields: migration; inequality; health – one could make a long list. So although peace research as a concept is perhaps less prominent than before, it is also more generally accepted. The themes, concepts and perspectives that peace research has put onto the global research agenda have a larger place than ever. Not a single week goes by when I don’t notice politicians, media commentators and intellectuals using Johan Galtung’s ideas from the 1960s. Positive/negative peace and structural violence have become inevitable parts of the international political vocabulary.

This also means that there are an incredible amount of smart people who now work on this type of research and help renew it, with regard to both method and theory. One of the themes that I’ve been curious about for many years, but which I haven’t worked on systematically myself, and also couldn’t find any really good research on, is how local communities adapt, survive and interact with the parties involved in difficult conflict situations. Then we see how in recent years, a number of new, extremely rigorous projects have emerged, which examine how local communities adapt, how they work with the armed groups in order to acquire some kind of security and scope for action. And what are the constraints, what are the types of conflict that make it most difficult for local populations to adapt? So there is a lot to look forward to within this field of research.

I agree completely. Let’s move to a different topic. I have worked a little with Turkey, where our strength used to lie in our collaboration with Turkish researchers. That has now become very difficult.

We are faced with irreconcilable dilemmas, which nonetheless give us an even greater responsibility to engage in the kinds of issues that have now in fact been put off-limits for local researchers. At the same time, COVID-19 makes this all the more difficult. Is it possible to change our ways of working? Are there themes, forms of collaboration that we can explore?

Your example of Turkey makes this dilemma clear. Researchers there used to enjoy complete academic freedom and could collaborate academically in a normal manner. But then there was a political backlash forcing them to be very careful with what they say or write. Russia is another example, although there the change has been more gradual. And we have seen a clampdown in China under Xi Jinping. So we have to turn our attention to how we can work academically with countries that lack academic freedom, be it China, Iran or Venezuela. What types of research collaboration do we have? In our field – peace and conflict research – there is scope for conducting the type of scholarly dialogue that is sometimes called ‘science diplomacy’. We have to open up and think more broadly. We can conduct scholarly dialogues with academic environments that are not necessarily similar to our own. These may be completely different types of knowledge environments. In many countries, heavyweight knowledge environments exist in the civil service, business, civil society, in all parts of society.