For Afghans, Christmas 2020 marked 41 years since the Soviet intervention. Ever since, this poor, mountainous country in Central Asia has been a focus of global attention. Can we now see signs of a peaceful solution?

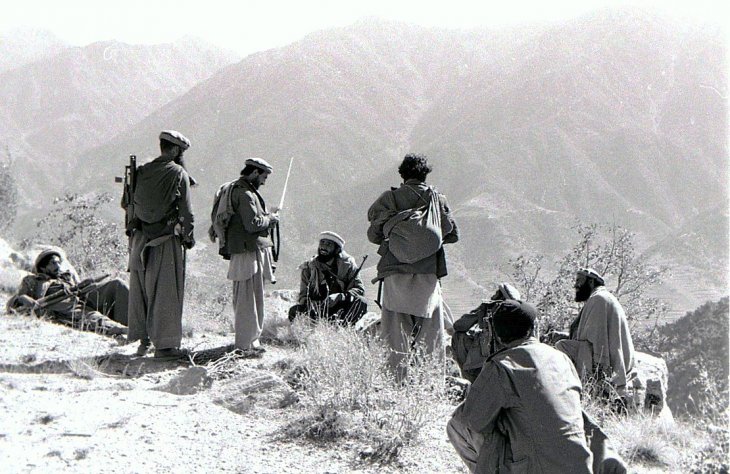

Afghan rebels in Kunar province in 1985. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A tweet posted on Christmas Eve by Muska Dastageer, a young Afghan woman with a sound basis for her opinions, could be read as a cry for help:

“As families come together this night, Afghans are away from, fear for and mourn their loved loved ones for the fourth consecutive decade. As a thousand hands from abroad continue to play with our lives, I wish peace to their nations and ask that they please will let us have peace too”.

Dastageer’s Christmas tweet made a deep impression on me. I believe that the roots of Afghanistan’s conflict are local, and that the solution needs to be Afghan. But there are unavoidable questions.

- Would the conflict have grown to such dimensions without external involvement?

- Have the Afghan people had a chance to negotiate peace on their own terms?

The uncomfortable answer to both these questions is no.

The Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan in order to salvage a communist regime facing imminent collapse. A collapse that was due to the regime’s extremely violent treatment of its own population. The Afghan Communist Party had seized power in a coup d’état in April 1978. The aim of the Soviet regime in Moscow was to salvage a neighbouring country’s communist government, just as it had done in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Soviet special forces killed the sitting Afghan president on 27 December 1979. Large numbers of Soviet troops then entered Afghanistan. Moscow wanted a communism with a more human face. The intervention took many lives and forced millions to flee their homes. Many Afghans experienced the Soviet presence as an occupation and an escalation of warfare.

The international community reacted strongly, and this soon translated into direct support for the fledgling Afghan resistance movement. This support united Islamic and Western countries, as well as uniting political forces from left to right. In Norway, there were spontaneous demonstrations between Christmas and New Year’s Eve in 1979. Strategists in Washington saw Afghanistan as an opportunity to inflict a mortal blow on the Soviet Union.

In Pakistan, fleeing Afghans had to register as members of resistance groups in order to gain refugee status. Seven resistance groups gained official approval. These groups were assigned central roles both in distributing aid to refugees and in sending money and weapons to fighters over the border.

After a while, foreign fighters began to arrive from other Muslim countries. Afghanistan offered opportunities for training. Money and weapons for resistance groups flooded in through the same channels. On the battlefield, the foreign fighters were of little significance.

In 1989, the Soviet Union withdrew its last soldiers from Afghanistan. Three years later, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Afghanistan’s communist regime collapsed. Factions from the government and the security forces merged with the various resistance groups. Kabul was divided up into ethnic zones. The resistance groups each took control over their own government ministries.

Before long, the heroes of the resistance were at war with each other. Civilians were mistreated or killed simply because they belonged to the wrong ethnic group. Outside the capital, the various warlords controlled their own territories, oppressing the local inhabitants and extorting taxes from travellers. When a new movement, the Taliban (made up mainly of religious students, taliban means “students” or “seekers of truth” in Pashto), emerged in autumn 1994, many people saw it as a sign of hope for a better future.

During the 1990s, Afghanistan’s neighbours were the dominant actors in the country. The rest of the world was more concerned about events in the Balkans, in Rwanda and in other places. Different countries in the region supported different groups. Just like today, their involvement in Afghanistan was not primarily Afghanistan-related. Pakistan, for example, which leads the list of countries that have played a destructive role in Afghanistan, was motivated primarily by its relationship with India.

In the 1990s, there were only three things that aroused interest in Afghanistan. The first was its exports of opium, which only increased in scale. The second was the human rights situation, particularly the position of women, under the ever-more-repressive Taliban. The third was the Taliban’s alliance with the international terrorist organization al-Qaeda, founded by foreign fighters from the 1980s. International attention was focused on these three issues when the UN Security Council imposed sanctions on the Taliban in 1999. The isolation of the Taliban was almost total.

But with al-Qaeda’s attacks on New York and Washington on 11 September 2001, Afghanistan once again became the focus of global attention. The alliance between al-Qaeda, a radical, internationally-oriented terrorist network, and the far more traditional and Afghanistan-focused Taliban was in many ways unnatural, an alliance born of necessity.

The alliance would cost the Taliban dearly. Their efforts to control al-Qaeda’s activities failed. The United States held the Taliban directly responsible for the 9/11 attacks, and viewed al-Qaeda and the Taliban as one and the same. Barely a month later, the American-led intervention began. The Taliban realized quickly that the battle was lost and withdrew their fighters. By early December, a new transitional administration was already in place.

This new administration was based on warlords from an older generation, who had previously been driven onto the defensive by the Taliban. As a result, one oppressive regime was swapped for another. International military operations became increasingly intense, particularly in areas were the Taliban had been strong, and the consequences for the civilian population were grave. Slowly but surely, the Taliban leadership succeeded in rebuilding their military organization, much assisted by the unpopularity of the international military campaign, but also with support from Pakistan and others.

Just over two years ago, President Trump decided that enough was enough. The United States initiated talks with the Taliban, contrary to the wishes of the Afghan government. In February 2020, the parties signed an agreement. The United States would withdraw its troops, and the Taliban promised not to allow international terrorists to operate on Afghan soil. A basis was established for direct talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government. After many, long-drawn-out discussions, the parties recently succeeded in agreeing on a set of rules that will form a basis for the talks. The talks are paused over the Christmas season, but set to resume on 12th January.

At the same time, American troops are departing, and everything suggests that Joe Biden will continue the withdrawal. The Taliban’s position has been strengthened by their agreement with the United States. The Afghan government wants a ceasefire, but the Taliban want to talk and fight simultaneously. The parties are far apart, and both will have to make painful concessions to get the talks moving. The peace process must be given time, and international actors must display patience.

In recent years, the conflict in Afghanistan has claimed more lives than any other conflict worldwide. Right now, we are seeing a new wave of terrorist attacks. A number of activists and journalists have been basically executed, and there is heated debate about who is behind these killings. Fears that the war will continue, and that the suffering will intensify, are great. Our hope is that 2021 will be a year when the violence subsides, and the distance between the parties gradually diminishes. Next Christmas, perhaps we will see hope for Afghanistan where conflicts are being resolved, not with armed force, but through political dialogue.

- This text is based on an op-ed which was first published in Norwegian in Vårt Land on 29 December 2020: Julebudskapet fra Afghanistan

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext ANS