A new conflict pattern has appeared in Myanmar. Amidst a spiraling economic, social and health crisis, armed fighting is no longer confined to ethnic minority areas but has cropped up in cities and regions where the ethnic Bamar are in majority. They see themselves as pursuing a nation-wide resistance. Preventive diplomacy is needed to stop the country’s descent into omnipresent civil war.

From protests to armed struggle

Following Myanmar’s military coup on 1 February 2021, an unprecedented non-violent Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) emerged and spread to most of the country. After some hesitation, the military (Tatmadaw) launched a brutal crackdown. The Tatmadaw’s reaction was not new. In 1988, it crushed a revolt in Yangon, killing thousands. In the 1990s, it killed much greater numbers of civilians when defeating the Mong Tai Army in Shan State and destroying the strongholds of the Karen National Union (KNU) in Kayin State. In 2016–17, it raped, murdered and burned the villages of the Rohingya in Rakhine State, driving 800,000 across the border to Bangladesh. These are just the worst examples.

What was new after this year’s military coup was the intensity of the protests in the regions and cities where the ethnic Bamar are dominant, as well as in the Kachin, Kayah, Kayin and Chin States. The non-violent movement reached its apex in March–April. Then it lost steam. Too many people were killed. Yet the movement remains active today. In the first week of November, flash mobs, street demonstrations, prayer marches and monk-led marches took place in at least 12 places. Since May, however, local activists have concluded that non-violence cannot work against reckless brutality. Myanmar’s majority population now view the Tatmadaw almost as a foreign occupation force. Military families are obliged to live inside military compounds.

Members of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy (NLD) have played a leading role in the emerging armed movement. This is new. The NLD has never called for the use of force in the past. After the coup and the incarceration of Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, NLD members with experience of non-violent struggle seized the initiative. First in the Civil Disobedience Movement. Then in the armed resistance that emerged in March–April and spread to more than half of Myanmar’s 330 townships.

The People’s Defense Forces (PDFs)

A number of new armed groups were formed during the crackdown in March. This was before the setup of the National Union Government (NUG) on April 16 to lead the resistance against the military junta. Fueled by a generation whose outlook was formed under Myanmar’s political opening 2011–20 and who knows how to use communication technology, the new armed groups have already proven themselves as a highly determined resistance movement. Sometimes they fight alongside Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) and receive weapons and training from them, but mostly they fight on their own. They do not yet depend on any central command structure although the NUG now does its best to develop command and control.

On May 5, 2021, the NUG decided to endorse and encourage the creation of People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) and, on September 7, it proclaimed a “nationwide defensive war.” NUG has since tried to raise funds and acquire weapons to equip the PDFs with a view to converting them to regular armed forces, organized in five military regions.

The spontaneous rise of the PDFs was much facilitated by social media (notably Facebook) and the encrypted communication apps Signal, Whatsapp and Telegram.

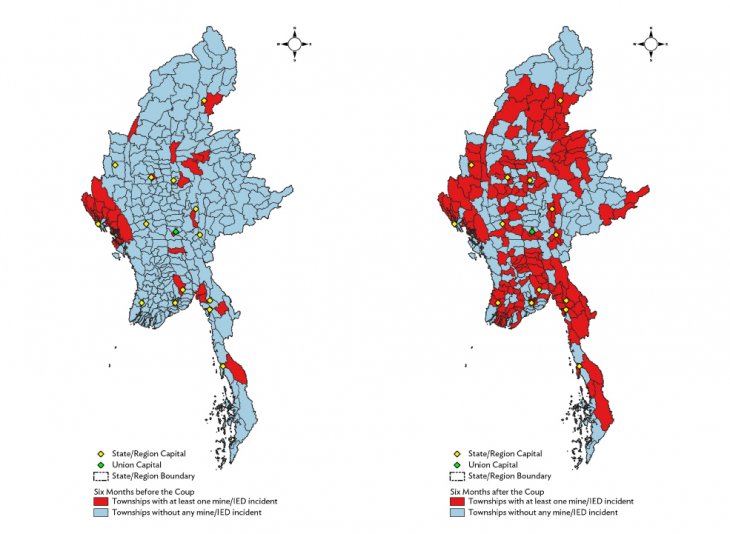

The escalation of armed conflict in Myanmar after the military coup on 1 February 2021. Townships with at least one Mine or Improvised Explosive Device (IED) incident during the last six months before the coup (Map 1) and during the first six months after the coup (Map 2). Source: Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security (MIPS).

Youths all over Myanmar learned how to make Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and to use them in targeted attacks, guided from mobile phones.

The PDFs use several tactics: Surprise assaults on small police or military units; burning of police stations, destruction of the military owned Mytel company’s telecom towers; and assassination of alleged collaborators. At least 730 assassinations of alleged collaborators were registered between 14 March and 2 November 2021. This wave of murders has undoubtedly deterred many local military supporters from accepting appointments from Senior General Min Aung Hlaing’s junta. It has failed to take control of local governance. In many places, local power remains in the hands of NLD adherents.

The junta has sought to alert international opinion to PDF “terrorism.” Yet these attempts have fallen on deaf ears since the Tatmadaw’s human rights violations are on a much higher scale. The NUG has set up a Human Rights ministry and officially prohibits any violation of human rights or the Geneva conventions. So far, however, the NUG has limited ability to constrain the locally formed armed groups, which are known as LDFs (Local Defence Forces).

The amorphous nature of the resistance movement and the strong support it receives from local communities makes it hard for the junta to quell it. The scene is set for a civil war that could either lead to a prolonged disaster or the downfall of the military regime. A key question is if the strongest of Myanmar’s ethnic minority armies will join in the fight.

The Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs)

While the Tatmadaw concentrates on repressing the resistance from the Bamar majority, some of Myanmar’s more than 20 ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) see a chance to expand their territories and local political power.

The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) is one of the strongest Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) in Myanmar. Its HQ is in Laiza, right next to the China border. Like other well established EAOs, it controls some territory and mostly operates in uniform. It had a signed ceasefire agreement with the Union government from 1994 to 2011. Fighting occurred intermittently during 2011–18. Then an informal ceasefire was put in place, which lasted till after the 1 February 2021 military coup. In March, when the military (Tatmadaw) shot and killed protestors in the Kachin capital Myitkyina, the KIA came under pressure from its grassroots to fight back. Intense fighting followed, with many casualties and internally displaced people. The KIA’s post-coup experience resembles that of the EAOs in Chin, Kayah and Kayin States, but differs from developments in Shan and Rakhine States, where fighting actually decelerated before and after the coup. Photo: Paul Vrieze / VOA / Public Domain

By contrast to the PDFs, most of them are not engaged in an existential struggle. They are in control of certain territories and have limited territorial aims. They often operate in uniform, tax local companies, provide rudimentary education and organize health services. They act like states in their local settings. In a recent study of Myanmar’s traditional pattern of conflict, we find that they rarely act in unison. When one group fights, others stay calm or agree to the Tatmadaw’s offers of ceasefire. If they are allowed to control some territory and uphold certain funding streams, they tend to stick to such ceasefires. Since 1989, this has allowed the Tatmadaw to divide-and-rule in the ethnic minority areas.

This pattern has not changed since the coup. In Kayin, Kachin, Chin and Kayah states – and in the Kokang autonomous area, local EAOs have engaged in fighting with the Tatmadaw, often alongside PDFs or LDFs. These are areas where the NLD gained huge support in the November 2020 elections. In most of Shan and Rakhine States, however, where the strongest EAOs are located, the Tatmadaw has not met active resistance. During 2018–20, Rakhine State saw intense fighting between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army (AA). In November 2020, however, it agreed to a ceasefire. This has allowed the Tatmadaw to concentrate on fighting the PDFs. It has also allowed the AA to reinforce its troops and create parallel local governance structures in north and central Rakhine.

In Shan State, only the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in Kokang has launched attacks against the Tatmadaw. The United Wa State Army (UWSA), the strongest of all of Myanmar’s EAOs, has stuck to the favorable ceasefire agreement it got in 1989, while supporting other EAOs with weapons and training. In north Shan, an alliance of two EAOs – the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and Shan State Progress Party (SSPP) – has launched offensives against another EAO instead of fighting the Tatmadaw. This other EAO, the Restoration Council for Shan State (RCSS), has decided to maintain its ceasefire agreement with the Tatmadaw while fighting the TNLA-SSPP alliance. The top leaders of the Karen National Union (KNU) also stick to their ceasefire, while some of the KNU’s local brigades are engaged in fighting the Tatmadaw.

It remains to be seen if the strongest EAOs will join the struggle of the PDFs against the military junta. Some of them have much to lose. On the other hand, if they do, the Tatmadaw might be forced to engage in talks with the NLD, NUG and the EAOs, reform itself and give up some of its political power. By joining and supporting the PDFs, the EAOs could strengthen their chance to obtain a federal compromise with large-scale local autonomy for ethnic states and autonomous areas.

ASEAN’s Opportunity

Myanmar’s descent into a vicious civil war is just one aspect of the crisis that has befallen its people since the 1 February military coup. The economic, social and health crises have brought even greater loss of life. The coup and its violent aftermath have had a deleterious impact on the country’s struggle with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The confluence of these several kinds of crises makes it all the more urgent to seek ways to stop the violence. ASEAN, with Cambodia as chair in 2022, may be in a position to help. With backing from the UN, China and all countries concerned with Myanmar’s stability, ASEAN should use all possible diplomatic means to obtain the release of President U Win Myint and State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the reinstatement of legitimate authorities in the capital Nay Pyi Taw.

Upon their release, the NLD leaders should obtain a pledge from the Tatmadaw and NUG – on behalf of the PDFs – to a general ceasefire. In order for this to happen, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing will have to resign and leave the Tatmadaw in the hands of a professional commander-in-chief. Negotiations could then begin with the ethnic parties and EAOs, for the establishment of an interim federal coalition government to prepare for free and fair elections to a new constitutive assembly.

- Stein Tønnesson is a Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).

Accept NUG , Reject Military.