Afghanistan’s “youth boom” means that the country has a large generation of young people with high expectations for a better future – and high levels of frustration. Such a situation provides fertile ground for radicalization.

Boys in Badakhshan: do they have a brighter future? Photo: Norwegian Afghanistan Committee, 2013

Afghanistan’s population is estimated to have grown by as much as 2.4 per cent in 2014, and around 68 per cent of the total population is under 25 years of age. The absence of a strong and responsive state means that young Afghans’ prospects and quality of life are blighted by lack of security, poverty, drug dependency, lack of educational opportunities, and unemployment.

At the same time, young Afghans’ expectations have risen steadily over the past 13 years as a result of Afghanistan’s increasing openness to the outside world. Exposure to the media and internet create demands for education, employment, better living conditions and greater buying power. Young Afghans want to live different – and better – lives than their parents’ generation, and they expect the government to provide them with the means to do so.

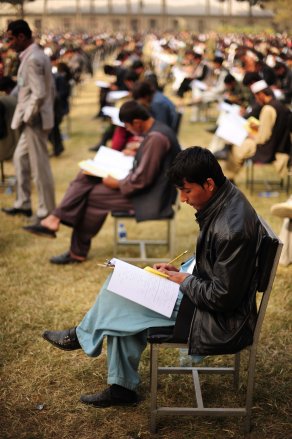

Examination day: young men at an upper-secondary school in Kabul. Photo: NATO

Young people’s raised expectations combined with government shortcomings have caused widespread frustration among young people in towns and rural areas alike. This frustration has in turn created an opportunity for political and religious movements to exploit and mobilize the younger generation. Along with ethnicity, religion has long been a key instrument for violent and non-violent political mobilization in Afghanistan. Political groups with overt religious agendas are hard at work influencing and mobilizing young educated women and men. These political-religious groups are inspired by, among others, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt (for Sunni Muslims) and the ideology of the Iranian regime (for Shia Muslims). These groups are exerting enormous influence on young people through mosques, universities and colleges. Using CDs and social-media platforms, such as YouTube, they are succeeding in spreading their messages to even wider audiences. The groups’ understanding of differences between young people in urban and rural environments enables them to target their media efforts in order to mobilize different groups. In particular, they understand the increasing power and significance of Afghanistan’s growing urban centres, and target their efforts to mobilize the large young urban population.

Opposing forces

Afghanistan is often seen as a regional battleground in the struggle between radicalized religious groups and democratizing forces. The country’s traditional social structures have broken down after many years of civil war, but there have been few meaningful attempts by young people to replace them. Young people’s exposure to the outside world has left them confused and searching for answers. They question old identities and loyalties, while at the same time Afghanistan still has far to go in building a new national identity.

There are two primary forces that are competing to fill this vacuum: on the one hand, there are people who want a process of democratization that would be led by Afghan civil society, politial movements and public authorities; while on the other hand, there are the more organized and focused radicalized forces, which enjoy broad support in rural areas.

Afghan civil society and democratizing political movements, which represent the counterforce to radical religious groups, have limited influence outside urban areas and suffer from a lack of coordination. They also lack deep-rooted popular support. They have a broad unofficial mandate and focus on all segments of Afghan society, not just young people. And they wrestle with multiple issues in the areas of security, human rights and the rule of law. In contrast, the radical groups have a single target group – young people – and a simple agenda. In addition, many of these groups enjoy historical legitimacy in a religious country such as Afghanistan. Civil society, which is mainly funded by international donors, has less credibility, not least among rural Afghans. As a result of the civil war and the brutal killings organized by “political parties”, many Afghanis are sceptical about political parties and movements.

The way forward

Although the “soft radicalization” of young Afghans has huge implications for the country’s future, the phenomenon is being largely ignored. “Soft radicalization” is a form of radicalization that does not directly encourage the use of violence, but justifies terrorists’ use of violence on religious grounds. It also promotes a culture of intolerance and disparages women and religious minorities. In the medium- to long-term, the soft radicalization of young people may have an enormous impact on the future of democracy both in Afghanistan and in the region as a whole. The radical discourse denies the importance of women and women’s role in society, condemns democratic politics, and encourages sectarian hatred between Shia and Sunni Muslims. In the longer term, these radical groups may train and equip an “army” of young Afghan men and women with thoughts and ideas that will encourage them to resist progress, marginalize or exclude creativity and innovation, choke freedom of expression and prevent the social, cultural and legal changes that could strengthen the rights of women and religious minorities. As of today, far too little has been done to create a counterforce to this radical “army”.

While attacks by the Taliban grab international attention, the radicalization of Afghanistan’s large youthful population, along with its potential social and political consequences, has been ignored.

We must hope that this issue will finally receive the attention it deserves from the newly formed National Unity government and Afghan civil society. In the absence of strategic and systematic efforts to counter religious radicalism, we may one day wake up to find yet another radicalized generation and a lost opportunity for democracy and development in Afghanistan.

- Guest blogger Shaharzad Akbar is chairperson of Afghanistan 1400, a political mobilization platform for young Afghans, and co-founder of QARA Consulting, a public relations and political risk consultancy.

- This blog post is published in connection with the Afghanistan Week 2015

- This text was first published in Norwegian: ‘En ung og sårbar tid’ (Norwegian Afghanistan Committee, 2015)

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext