On Oct. 25, Ivorians head to the polls for their first presidential election since the disputed 2010 election that left more than 3,000 dead and more than 500,000 displaced. Despite the previous electoral violence and a decade of civil war and political turmoil from 2000-2010, most discussion before this election has been about the country’s remarkable economic resurgence.

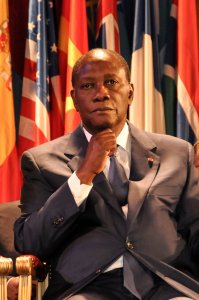

Incumbent president Alassane Ouattara is the favourite for this year’s election. PHOTO: Creative Commons.

Once known as the “Paris of West Africa,” the commercial capital Abidjan and the country more generally are again benefiting from high cocoa prices and investor-friendly policies. The World Bank estimates a growth rate of approximately 8.7 percent over the last two years.

Many analysts and Ivorian citizens believe (or hope) that the economic boom will help defuse political hostilities between the opposition parties, led by the Front Populaire Ivoirien, and President Alassane Ouattara’s ruling party, Rassemblement des Républicains. The underlying assumption is that with a growing economy, the ruling party can consolidate political support and reduce the likelihood of a closely contested election. And it does appear that the incumbent president Alassane Ouattara will win big.

Political scientists suggest that it is only when vote margins are very narrow that candidates and their supporters may resort to violence to prevent competitors from voting. Violence provides a way of “redistricting” by eliminating opposition supporters from competitive areas. After voting day, violence can escalate if politicians or supporters protest the poll results.

But can we expect economic growth to yield violence-free elections?

- Read more at the Monkey Cage, where the complete text was published 20 October 2015.

- The blog post is based on the author’s article in Journal of Peace Research: ‘Land grievances and the mobilization of electoral violence

Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire and Kenya‘