European news headlines in 2015 have been all about the refugee crisis and religion-based terrorism. Is there still room for discussing “peace”? Should we not concentrate on bombing ISIS and protect national security?

Yesterday, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet. This quartet consists of four organizations – with distinct differences – that have contributed to brokering a foundation for a democratic, rights-based society in the former French protectorate in Northern Africa. The situation in Tunisia is tense. Internal rifts, impulses from other countries that have more or less broken apart after the “Arab Spring”, along with recent acts of terror, may lead to failure for the Quartet’s endeavors. The Peace Prize is a small push in the right direction for Tunisia. If the fragile democracy crumbles and religious extremists try to establish an order of their own, will the Nobel Committee’s choice of 2015 laureate be shown to be wrong?

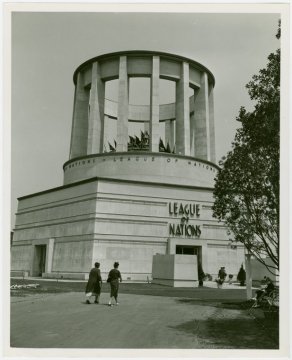

The world wars changed the conditions of international peace politics. Here, the League of Nations building at the world fair in 1939.

Since 1901 the Nobel Peace Prize has been part of a running discourse of peace politics around the questions “What is Peace?” and “How to Promote Peace?”. The answers to these questions have developed over time. In the years leading up to World War I the situation was quite similar to the one known to Alfred Nobel when he wrote his testament in 1895. International politics was dominated by the great European powers, and peace discourse focused first and foremost on preventing war between these powers. People and countries outside Christianity were generally considered uncivilized, or “half-civilized” at best. Many in the peace movement on both sides of the Atlantic saw it as a natural obligation to promote the blessings of European culture in the world at large.

The 1909 Peace Prize laureate, the Frenchman Paul Henri Benjamin Balluet d’Estournelles de Constant, is a good example. He was a politician, a jurist and a diplomat, and had served as the representative of the French state in Tunis. He was not in doubt that European influence – and French influence in particular – was good, but he was critical as to how this dominance was managed. If the European leading position was based mainly on military superiority, he was convinced that a great majority of non-Europeans eventually would strike back. He also pointed out a dilemma: If young men were sent out to safeguard the supremacy of their countries by using brute force, it was likely that many of them would bring the very same brutality home with them.. The liberal and humanistic values making the European dominance “acceptable”, would then quickly be lost.

The world wars changed the conditions of international peace politics. To a much greater extent, peace became a concern of governments. This was expressed by the establishment of the League of Nations, and later the UN and other intergovernmental organizations. Among the Nobel Peace Prize laureates were several members of national governments and people involved in the work of these large organizations. The list of laureates reveals another important development: There were fewer Europeans.

Everything from forestation to micro credit has become “roads to peace”. The concept of peace is therefore manifold. Peace Prize Laureate 2004 Wangari Maathai, who received the prize ‘For her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace’

But what was the meaning of «peace»? The answer must be that the term covered more and more. In the beginning it was about absence of war. Many believed that peace could be achieved through arbitration, disarmament and, indeed, international organization. Following World War I it became clear that oppression of minority groups and lack of democracy within states could entail a risk of war between states. Later, the experience of Nazism and the Holocaust encouraged the idea that respect of fundamental human rights was a prerequisite for peace. During the Cold War, universal human rights became a weapon in the ideological battle against communism, and also in the battle against the racial segregation in the US and in South Africa. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the South-African Albert Luthuli, the American Martin Luther King Jr, and the Russian Andrei Sakharov.

The 25 years following the fall of the Soviet Union and Apartheid have led to a further expansion of the concept of peace. Everything from forestation to micro credit has become “roads to peace”. The concept of peace is therefore manifold. The aim is not religious salvation or the realization of a political Utopia. It is rather to make a manifold of political processes happen in accordance with institutionalized norms.

The latter point is important. This year’s Peace Prize laureates represents forces that are often opposed to each other. The four have led a broad dialogue to establish a legal framework for a social order that allows change without war. This has happened not the least to counteract forces like ISIS gaining new ground. Whether the Quartet succeeds or not, the Peace Prize, with its long history, remains a weapon in the battle within the Muslim world. As opposed to more traditional security policy tools, this weapon does not separate between “us” and “them”. The prize may also have a positive impact in the European context: We are compelled to see the manifold peace as part of our defense against terrorism, not just as something we have to defend.

- This article was first published in Norwegian in Fædrelandsvennen 9 December 2015

- Translation from Norwegian: PRIO