After traveling in Cuba for two weeks, I sit down to reflect: What is Cuba?

- A socialist laboratory for Che Guevara’s ‘New Man’?

- A vast outdoor museum of Spanish colonial architecture?

- An extraordinary collection of sixty-year old American gas-guzzling automobiles?

- A zoo for humans (excellent health care, low infant mortality, high life expectancy, cheap housing, adequate nourishment, and low personal freedom)?

- A land freed from the yoke of North American economic and political imperialism, or

- a bankrupt country subsidized successively by the Soviet Union, Venezuela, and Cuban emigrants?

- A tourist paradise with endless white beaches and all-inclusive hotels?

- A pawn in a game between big powers?

All of those, and more, although the New Man is fading into the background.

The author as a tourist in Cuba, 2017. Photo: Private

Young people mark time until they can collect enough money to leave for other countries, as noted by American journalist Julia Cooke in her 2014 book The Other Side of Paradise. Life in the New Cuba. And as confirmed by a young Cuban, by no means a dissident, who lets me know that half his friends have left the country.

There are cheerful and friendly people everywhere, but also beggars at major tourist locations.

Freedom of speech is practised mainly from abroad, as illustrated by the homosexual author Renaldo Arenas in his memoirs Before the Night Falls; he won national literary prizes but couldn’t get published in his own country. A very limited freedom of speech is exercised from the inside by people like Yoani Sánchez in her blog Generation Y and in her book Havana Real, by a few independent newspapers sponsored by Instituto Cubano por la Libertad de Expresión y Prensa and supported by, inter alia, Norwegian Fritt Ord Foundation, and by groups such as the Damas de Blanco – Ladies in White – with their weekly public march in Havana.

Cuba provides plenty of echoes of the last years of the Soviet period with revolutionary slogans mouthed with declining conviction. Yoani Sánchez tells a revealing story of her initiation into the Pioneers when, imbued with the enthusiasm of the early years on the revolution, she cheerfully donned the blue neckerchief and joined in the collective wish to be like Che. Thirty years later, her son faces the same ceremony. He keeps his mouth shut and the teacher asks him why he does not join in the chorus. ‘Che is dead. I don’t want to be like him.’ His mother is gripped by fear that he will get labeled C for counterrevolutionary. Instead, the teacher laughs, ‘Oh, why don’t you just say the slogan, why make problems for yourself?’ From revolutionary fervor to opportunistic adaptation in one generation.

Nobel economics laureate Herbert Simon in his memoirs Models of My Life belittles the value of visiting foreign countries. Indeed, a ‘travel theorem’ is now credited to his name:

‘Anything that can be learned by a normal American adult on a trip to a foreign country (of less than one year’s duration) can be learned more quickly, cheaply, and easily by visiting the San Diego Public Library.’.

For a seasoned traveler, professionally as well as for pleasure, this is hard to take. Is seeing, hearing, and smelling Cuba for myself of no value?

Of course, when you travel in an authoritarian country, you cannot avoid being influenced by what the authorities want you to see, or not to see. Travel tour organizers are also somewhat constrained in their ability or willingness to show the reverse side of the medal. No visit to Buenos Aires is complete without visiting Plaza de Mayo, where the mothers and grandmothers paraded during the years of the military dictatorship asking after the fate of their offspring who ‘had been disappeared’. But tour guides do not take their flock to St Rita’s Church in Havana on Sundays to see the Damas de Blanco parade in support of relatives who were arrested in the Black Spring in 2003.

Herbert Simon’s pessimistic view of foreign travel is confirmed on several occasions. Santa Clara is a must on a grand tour of Cuba. You get to see the remnants of the train with arms and troops meant to relieve Batista’s beleaguered forces, but halted by the second column of the rebel forces commanded by Che Guevara. And, next door, the Che memorial with his mausoleum. Che’s diaries (surprisingly candid) are on sale in multiple languages in all major tourist locations. Yet, one can probably learn more about the complex life of the revolutionary hero by reading books such as the twenty-year old biography Compañero by Mexican historian/political scientist and former communist (and, more recently, Foreign Minister) Jorge Castañeda.

A tourist visit provides little opportunity for talking to locals, apart from those engaged in the tourist trade. You can stay in a casa particular, a bed and breakfast. But unless you speak Spanish, communication will be limited. And if you do, will you have time to really get to know your hosts and overcome their potential fear of being reported to the local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution and lose their livelihood?

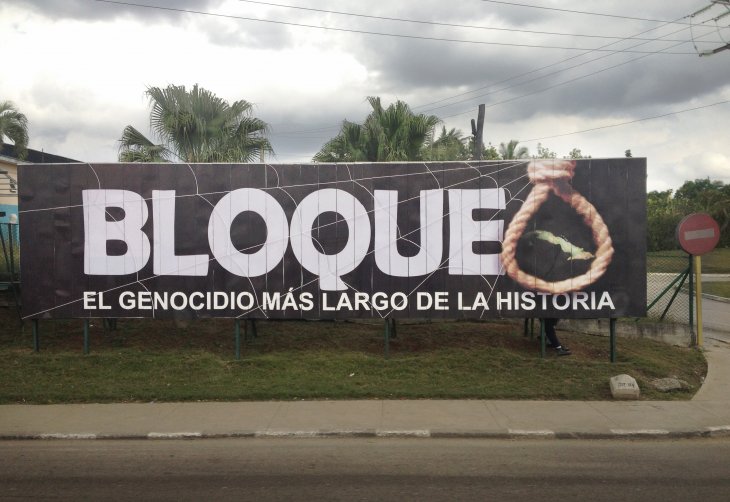

The greatest genocide in history? A view from the window in the tour bus. Photo: Private

Cuban universal education and health care are justifiably applauded, even if strained in the current economic crisis, and you are regularly reminded of these achievements when you pass local health clinics, by suitably posted quotations from the recently deceased líder máximo, or by your tour guide. However, chances are that you may have to go to your academic library to be cognizant of the strong position of Cuba in education and health care even prior to the revolution in 1959.

But, of course, my reading is not neutral either. Although I don’t think I inhabit an echo chamber either at work or at home, as a defector from dependency theory to a liberal worldview (some twenty years ago), I am probably somewhat selective in my reading. So exposure to the worldview espoused by the Cuban authorities (and by many Norwegians) is probably useful as an antidote. Besides, if you keep your eyes open, you can observe – in addition to the many attractive sights that are proudly displayed by the regime – the poverty, the dilapidated buildings, the rundown infrastructure, and the lack of public transportation. And you may begin to suspect that not all of this can be fully explained by the US economic boycott, even if a propaganda poster proclaims that the embargo is the greatest genocide of all times.

So I cannot avoid the rather unexciting conclusion that the best recipe is to supplement your visit to Cuba with a visit to your library. Or vice versa.