Photo: HBO

In my last Game of Thrones blog post I looked into whether there were any similarities between the War of the Five Kings and modern war in the real world. I found a surprisingly large number of similarities. Now that we have seen the end GoT, and we know who sits on the (non)-Iron Throne (and other thrones), the question remains: can we expect peace to last in Westeros? To answer this, we need to know a bit about how conflict ends and what makes peace stick.

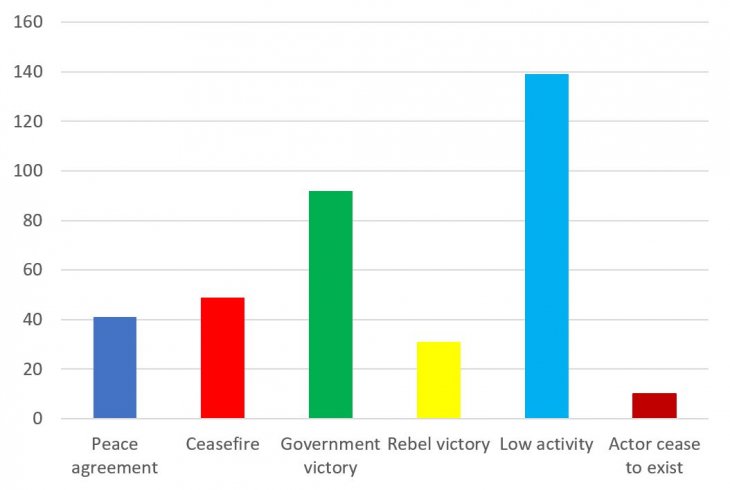

According to the UCDP Conflict Termination dataset there are several ways a conflict could end (see Figure 1). The most common is that the conflict slows down, and the level of violence becomes so low that we don’t consider it a conflict anymore. The second most common termination is victory for the Government. Now, neither of these types of termination fit what we saw in the final episodes of GoT, as the violence definitely did not cool down with Dany’s dragon rampage, and Cersei, who we would consider the government as she was holding Kings Landing and the Iron Throne, did not win.

Figure 1: Kreutz, Joakim. 2010. “How and When Armed Conflicts End: Introducing the UCDP Conflict Termination Dataset,” Journal of Peace Research 47(2): 243-250.

However, it is more difficult to decide which of the four remining categories actually applies to GoT. There is a clear military victory to Dany, the Dothraki and the Unsullied, as they burn the city and kill off anyone supporting Cersei, even after they surrender. Nonetheless, it is clear that Dany wants to continue to fight after King’s Landing is defeated, hence her victory did not really terminate the conflict. Further, when Jon kills Dany an important conflict actor ceases to exist, and thus we could put it into this small category. Yet, it turns out that even when their Queen is dead, the Unsullied still want to fight. However, the conflict seems to end when the lords and ladies of the noble houses comes to an agreement with the Unsullied, and Bran the Broken is chosen to be king. Thus, the actual ending of the war in Westeros seems to be terminated with a negotiated settlement, whether we call it a peace agreement or ceasefire.

Has there actually been a peace process in GoT? A peace process is often initiated by at least two of the actors being willing to talk. I argue the peace process is triggered when Jon travels to Dragonstone to negotiate with Daenerys, and concurrently bends the knee to her. Both Jon and Daenerys represent non-state actors that are in opposition to the Iron Throne.

But how can we know this agreement will hold, and peace will stick? To better understand this, we need to look at the process leading up to the negotiated settlement. Peace processes often last many years, and conflict often go through several peace process before peace sticks. For example, in Colombia we have seen five peace process since 1989, before we finally seem to have an agreement that is bringing peace to the country.

To answer the question, we need to look into the Westeros peace process. The first question that comes to mind is of course: Has there actually been a peace process in GoT? A peace process is often initiated by at least two of the actors being willing to talk. I argue the peace process is triggered when Jon travels to Dragonstone to negotiate with Daenerys, and concurrently bends the knee to her. Both Jon and Daenerys represent non-state actors that are in opposition to the Iron Throne. Daenerys wants to take over the Iron throne, while Jon more reluctantly has accepted to be the King in the North, and thus is representing a secessionist movement.

Jon Snow: (temporary) King in the North, and man in love with his aunt. Photo: HBO

Nonetheless, the two insurgents are joined in a fight against a common, outer enemy: The Night King. In the season finale of season 7, all the noble houses are gathered in King’s Landing to discuss how they should deal with the threat beyond the wall. This common enemy has brought them together, leading to all the warring parties, including Cersei, agreeing to a ceasefire.

A ceasefire is “an explicitly declared intention, by at least one belligerent, to suspend hostilities from a specific point in time. This [definition] of a ceasefire captures the full range of security arrangements through which belligerents might agree to temporarily suspend and/or terminate hostilities.”

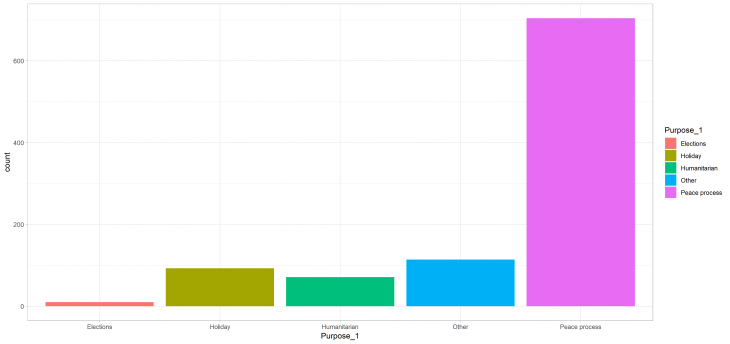

This definition comes from the new and soon-to-be-published dataset ETH-PRIO Civil War Ceasefire Dataset. This will be the first ever global dataset including all civil conflict ceasefires. In addition to information about timing and actors, the dataset also disaggregates ceasefires both on type and comprehensives. We see in figure 2 that globally the main share of ceasefires is tied to peace processes. However, ceasefires can also fulfill other purposes such as humanitarian needs, holidays and elections. For example, in Yemen the ceasefire that was signed in December 2018 was clearly geared towards the humanitarian needs for the Yemen population. It had a limited geographical scope (Hodeida), and it did not aim to end the civil war as such. On the other hand, in the Philippines, we see a large number of ceasefires being declared over Christmas.

Figure 2: Purposes of ceasefires.

While the Westeros Ceasefire can be argued to be part of a peace process or at least triggering a peace process, it probably belongs to the “other” category, since there is no category for “joining forces to kill the undead and the Night King”. Nonetheless, this ceasefire is a break in the violence between the parties, and they all agree to contribute to the army that is sent north to fight.

However, ceasefires can easily be broken. They are built on trust, and when someone breaks this trust the results can be more violence rather than less.

However, the intent in declaring a ceasefire is not always good. Some groups use the ceasefire to get breathing space to rearm and reorganize. For example, in Sri Lanka during the 2002 ceasefire the Tamil Tigers used the ceasefires to undertake a campaign to eliminate their political opponents, and thus strengthen their position until after the ceasefire. Similarly, in 1999, the FARC guerilla used the Caguan peace talks as a disguise to rearm and reorganize. This made it much more challenging to reach agreements later as the Colombian government did not trust the rebel groups to hold the ceasefire terms.

This is exactly what Cersei does in GoT. She promises that she will send parts of the Lannister army north to fight the White Walkers, but instead she is plotting with Euron Greyjoy to buy the Golden Company, and create an even greater stronghold in King’s Landing while the others fight the war in the North. This is a clear breach of the ceasefire.

A second threat to ceasefires is when rebel groups splinter, and one group is not keeping the agreement. Asal, Brown and Dalton (2012) found that “organizations with a factional or competing leadership structure and those that use violence as a tactic are at a greater risk to split”. For example, in 1996 the Government of the Philippines signed a peace agreement with MNLF. However, in 2001 the MNLF leader Nur Misuari was removed from office due to corruption charges. This leads to a splintering of the MNLF between the Nur Misuari fraction and the original MNLF groups. While the original group remained within the peace agreement, the splinter group returned to violence (Ryland et al 2018).

That one time people managed to compromise during Game of Thrones. Photo: HBO

All through season 8 we see that Daenerys is not able to rally the same sort of support in Westeros that she did in the Free Cities – instead Jon is enjoying the support and admiration of the people. In addition, when she learns about Jon Snow’s true identity and his claim to the throne, we see that there is a growing competition between the two.

Further, Asal, Brown and Dalton point out that using violence as a tactic also increases the likelihood of splintering.

We see this clearly in Nigeria. Boko Haram pledged allegiance to IS in 2015 under their leader Shekau. However, in 2016 a fraction of the group splintered and became what is known as the Islamic State in West Africa, or ISWAP. This group is directly supported by the IS head quarters in the Middle East. While ISWAP is a violent organization and has conducted a number of attacks against soldiers and military installations, they distinguish themselves from the original Boko Haram by refusing to kill Muslims.

While most groups in GoT use violence, some groups use more unnecessary levels of violence than others. Tyrion and Jon use a “winning hearts and minds” tactic similar to the ISWAP. They did not want to harm the innocent population of King’s Landing. Daenerys on the other hand did not show any mercy for Cersei or anyone else in King’s Landing, and kills innocent women, men and children in streets of the city. In fact, her actions very much resemble a genocide. During this rampage, we see Jon telling his Northern troops to fall back. This is a clear break in the insurgence allegiance.

Thus, there are two main reasons for why the first Westeros Ceasefire did not hold. First of all, Cersei took advantage of the situation and rebuilt her army. Second, through season 8 it is clear there is an escalating risk for splintering of the insurgency groups (i.e. Jon and Dany).

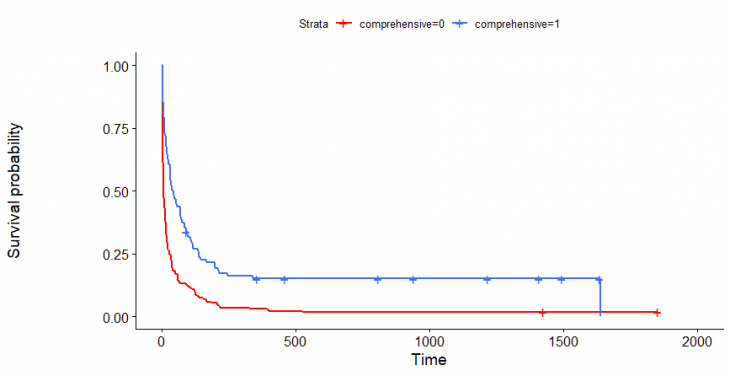

Now, the question is: how certain can we be that the second Westeros ceasefire/peace agreement will hold? Very recent research on the duration of ceasefires shows that ceasefires that are more comprehensive are more likely to last longer (Sagård 2019).

In the Kaplan-Meier plot in Figure 3, the X-axis indicates the number of days a ceasefire lasts, while the Y-axis indicates the share of ceasefires that end at a give time. The blue line indicates comprehensive ceasefires, and the red the non-comprehensive. We see that the red line “falls” at a much steeper rate than the blue, suggesting that comprehensive ceasefires last longer than the non-comprehensive.

Figure 3: Sagård, Tora (2019) Causes of Ceasefire Failure. A Survival Analysis, 1989-2017. MA thesis, Department of Political Science, University of Oslo.

The first Westeros ceasefire was not very comprehensive; it was an agreement to stop fighting until the Night King was slain. The second Westeros ceasefire/peace agreement was on the other hand very comprehensive.

First of all, in was an agreement amongst the elite on a new leadership structure. Bran was elected as king, and it was agreed that from now on the king would be elected and not designated by birth. Sam even tried to establish democracy, but was ridiculed for suggesting it. Nonetheless, the problems with competing leader structures that Jon and Daenerys were suffering from was resolved.

Sansa Stark, Queen in the North. Photo: Helen Sloan/HBO

Second, throughout all eight seasons, the North has been fighting for independence. First through Rob as the King in the North, and later when Jon was given the title. However, in the peace negotiation in the Dragon pit in the series finale, Sansa declare the North as an independent country, and is granted this by the new King Bran without conflict. Sansa is later crowned the Queen in the North.

Finally, the second Westeros ceasefire/peace agreement includes a prisoner exchange, which is a very coming trait of ceasefires. Since Jon killed their Queen, Grey Worm and the Unsullied are not willing to release Jon without any punishment. Thus, to keep the peace, Bran agrees to sentence Jon to “take the black” and return to the Wall in exchange for the Unsullied to leave King’s Landing and Westeros.

Thus, taking into account what we know about conflict termination, peace agreements and ceasefires, the Second Westeros Ceasefire/Peace agreement stands a good chance to make peace stick in the Six Kingdoms and the North. Although we should consider that Drogon could prove to be a spoiler to the peace agreement if Bran doesn’t manage to find him.

Drogon: a non-state actor? Photo: HBO