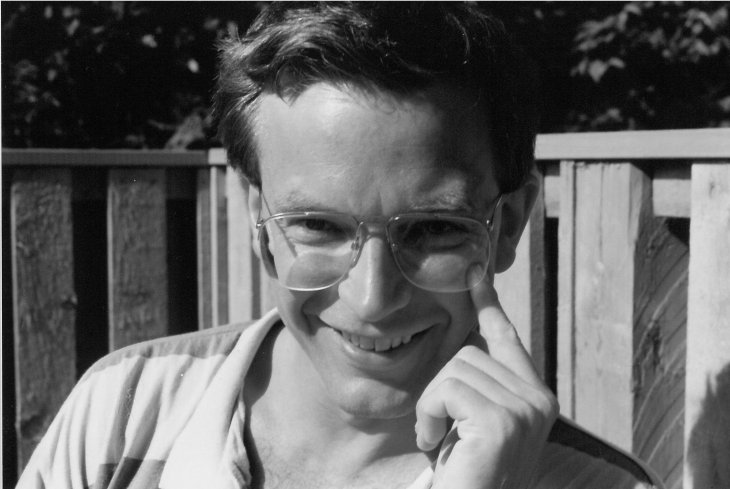

Stein Tønnesson in the early 1980s, when he held a student scholarship at PRIO. Photo: Stein Tønnesson’s archive

When looking back, I find nine paths I have explored in a quest to understand war and peace: War as war, war as horror, outbreaks of war, severity of wars, war endings, peace viability, regional transitions to peace, peace practices, and peaceful “utopian moments”, such as 1948, when the UN Declaration on Human Rights was adopted. A possible tenth path is one I have mostly shied away from: major peaceful utopias, such as a Harmonious or a Classless Society. While I have walked on all nine paths, the three I have travelled the most are outbreaks of war (in Indochina), transitions from widespread war to relative peace (in East Asia), and a peaceful utopian moment (the 1973–82 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea).

My studies of revolution and war in Indochina (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia), and also elsewhere, have led me to a conviction that peace, almost any kind of peace, is preferable to war. War rarely leads to any positive improvement, and entails enormous suffering. I define “peace” as absence of war and violence, and I see such absence as desirable in almost every situation. Since war and violence are negatives, the mere absence of war and violence is already positive peace. The term “negative peace”, I think, is a misnomer. If the absence of war is “negative peace”, then violence – the opposite of peace – would be positive, which is absurd. A mere absence of war is already positive peace. Yet it may be just a minimal, fragile or shallow peace. Peace building, as I see it, is about transforming a minimal peace to a deep and viable peace.

“Structural violence” is another term I see as misleading. If we call injustice, inequality or exploitation structural violence, then this may lead to the conclusion that we have a right to counter the structural violence with violence, and thus we have an argument for war.

Although PRIO has been dominated by the social sciences, it has also been a scholarly home for historians, philosophers and theologians. In this essay, which I first presented as a keynote address to the Norwegian History Days on 1 June 2018, I try to make sense of my life as an international historian and peace researcher.[1]

An essay by Stein Tønnesson

I was trained as an international historian, first by my father at the dinner table, and then at the universities and colleges of Århus, Lillehammer and Oslo. I have spent long days with loads of files in the national archives of France, Britain, the US, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore – and Norway. Yet I did not seek a university career. During most of my professional life, I have thrived at multi-disciplinary research centres: the Norwegian Institute of Defence Studies (IFS) in Oslo, the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS) in Copenhagen, the Centre for Development and the Environment at the University of Oslo (SUM), the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) in Washington DC, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University, and notably the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), where I was an MA student 1980–82, a doctoral student 1988–91, director 2001–2009, and am now a research professor. At present, I work in close partnership with the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security (MIPS) in Yangon.

This is the first time I have made a systematic attempt to give meaning to my professional life. I felt a sense of relief when discovering that it seemed possible. All my nine paths appear in some way to have helped me understand how war and peace have come about historically, and how peace may become viable.

I believe strongly in the possibility of learning from history. What else could we learn from?

The main source I have used for this essay is my Curriculum Vitae (“course of life”). That is where I found the nine paths that cut through my life as a peace historian.

First Path: War as War

The first path is not exactly peaceful. I call it the study of war as war. My ventures into war studies have allowed me to meet and learn from security analysts and strategic thinkers at thinktanks and military academies, notably in China, Vietnam and the US. I have tried to use the same methods as they do, and have learnt to cite authorities such as Sun Tzu, Carl von Clausewitz and Admiral Alfred T. Mahan. “Know thy self, know thy enemy”, says Sun Tzu. So, if war is my enemy, I must know war.

When I tell my Chinese colleagues, many of whom are hard realists, that it does not make sense strategically to build fortresses on underwater reefs in the South China Sea, since the US Navy can destroy them at will, my argument stands and falls with strategic reasoning. My motive, however, for advancing this particular argument is my wish for peace around China.

As a kid in Bærum, west of Oslo, Stein Tønnesson was engaged in many fights between “cowboys and Indians”. For a similar experience in a later Norwegian generation, with “cowboys” having been replaced by US army soldiers and “Indians” by Vietnamese guerrillas, see Johan Harstad 2015. Max, Misha og Tetoffensiven. Photo: NTB Scanpix

Military matters have always fascinated me, although there are no military officers in my family. I trace the fascination back to my childhood in Bærum, Oslo’s rich suburb in the west, where we replayed the battles between cowboys and Native Americans (whom we called “Indians” at that time). I made multiple drawings of guns as a little boy and resented my peace-loving parents, who took me to demonstrations against nuclear arms and denied me the right to carry a handgun when all the other boys in our neighbourhood – and some girls too – had guns aplenty. Poorly armed as I was, I was shot dead all the time, and forced to lie face down while counting to fifty.[2]

As a teenager I devoured books about Alexander the Great, Harald Fairhair, Genghis Khan and Napoleon Bonaparte; I remember how much it annoyed me when a book about King Charles XII of Sweden allowed a cavalry regiment to play a decisive role on the right flank when it was actually situated on the left flank. I had drawn a sketch of the battlefield, with units in their right place.

My two main heroes until I discovered Chairman Mao Zedong were Winston S. Churchill, who saved England, and Colonel Birger Eriksen, who rescued the Norwegian government from total humiliation in April 1940.

More recently, I had mixed feelings when watching the film Darkest Hour and hearing Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax put forward the same peaceful arguments for seeking Mussolini’s help to negotiate with Hitler that I myself have advanced in favour of talking to Kim Jong Un. My former hero Winston pursued his irrational instincts and opted for war at all costs.

Since his childhood, Stein Tønnesson has been fascinated by the drama that took place in the entrance to the Oslo Fjord in the early hours of 9 April 1940, when Colonel Birger Eriksen ordered the sinking of the German cruiser Blücher. Photo: Riksarkivet / Wikimedia Commons

It was not until my university studies that I began to empathize with the 1,000–1,400 Germans who perished when the cruiser was bombed and torpedoed from Oscarsborg by Colonel Birger Eriksen on 9 April 1940, thus allowing the Norwegian king and government to escape from Oslo and resist the German invasion. When I first heard that German soldiers who managed to swim and climb ashore in the Oslo fjord were given food and warm clothes by Norwegian civilians instead of being rightfully killed, I was appalled. It took time for me to understand that, in 1940, guerrilla warfare remained unthinkable for Norwegians. War was for soldiers in uniform.

Guerrilla warfare, which is integral to a strategy called People’s War, would later become a key research interest of mine. In my youth, which coincided with the Vietnam War, I shared the idea that guerrilla tactics is a legitimate weapon of the weak. By hiding among the people, revolutionary fighters with popular support can win protracted struggles against militarily superior oppressors. I admired the revolutionary ideologues of People’s War: Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh, Truong Chinh and Vo Nguyen Giap.

Later, I discovered that the oppressive government armies of Indonesia and Myanmar (Burma) also adhered to the doctrine of People’s War, and that the British were inspired by the same doctrine in their counter-insurgency warfare in Malaya. Government armies used it against communists and ethnic separatists. In Myanmar, there was People’s War against People’s War. The Indonesian Army also used People’s War against communists but, surprisingly, the Indonesian communists did not resort to arms but allowed themselves to be massacred in 1965. In Myanmar, People’s War led to a proliferation of local ethnic armies and militias who still fight each other and the government today. Myanmar’s civil wars can now be followed – and influenced – in real time on Facebook.

At some time in the 1980s, I realized that regardless of who claims to represent the People, the blurring of distinctions between soldiers and civilians has horrible implications. There is a cynical rationale behind guerrilla tactics; its aim is to provoke the adversary to kill civilians by making it impossible to distinguish between soldiers and civilians. This is meant to alienate the population from the adversary and increase support for oneself. When ethnic groups choose opposite sides, this creates popular animosities that last through generations.

Guerrilla tactics serve to pull civilians into warfare both as victims and perpetrators and do much to increase their suffering. The result has been to prolong civil wars, sometimes indefinitely. Only in a few countries, such as Vietnam, have guerrillas been able to win their wars and seize power, and this has required massive outside help to surpass guerrilla tactics, build a conventional army and fight big battles. In the end, moreover, it has not led to any deep peace, but to repressive and sometimes aggressive regimes.

Even the United States, a superpower, has used guerrilla tactics. It learned its lesson in Vietnam during the 1960s–70s, and turned guerrilla tactics around, using that method in “low intensity warfare” in Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia and other places, with devastating consequences for the local populations. I have long regretted my youthful admiration for guerrillas. The best weapon of the weak is ahimsa: non-violent struggle. It also sometimes leads to horrible defeats, but when it succeeds it creates more peaceful societies. Peace researchers have moreover found that non-violent rebels achieve their aims more often than the violent ones.[3]

Second Path: Horror

My second path is the study of evil: destruction, murder, torture, rape, massacres and other atrocities. We should remember those who suffered and died, raise awareness of the risk of war, and remind new generations of its dreadfulness. A recent essay by Vietnam War veteran reporter Max Hastings in The New York Review of Books notes with satisfaction how rare it has become to glorify war and concludes by endorsing a quote from the Norwegian Resistance fighter Knut Lier-Hansen, who blew up the ferry SF Hydro on Tinnsjøen on 20 February 1944, causing the loss of eighteen lives, including fourteen civilians. Lier-Hansen, who lived until 2008, stated: “Though wars can bring adventures which stir the heart, the true nature of war is composed of innumerable personal tragedies, of grief, waste and sacrifice, wholly evil and not redeemed by glory.”[4]

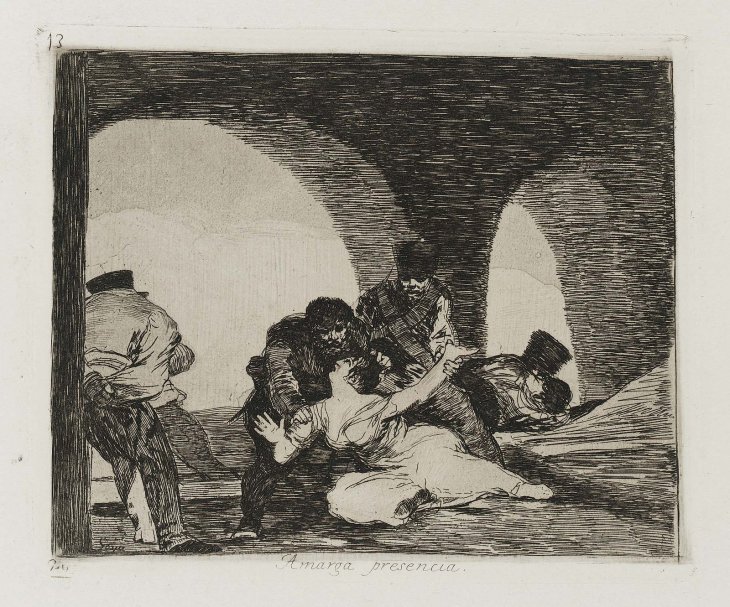

“Amarga presencia” (Bitter presence) was the title set by Francisco Goya on this drawing showing the atrocities perpetrated by Napoleon’s imperial army in the Spanish War of Independence. Illustration: Francisco Goya y Lucientes / Printer Workshop of Laurenciano Potenciano / Museum of Fine Arts Boston

The slaughters in the First World War did much to end the glorification of war in Europe. Yet tales and sketches of horror have been with us from long before. I have at home two volumes with reproductions of Francisco Goya’s Desastres de la guerra, his drawings from the guerrilla war in Spain against Napoleon’s imperial army 1807–1814. Among them is a depiction of a husband with his hands tied behind his back watching three soldiers rape his wife and daughter. The women are victimized; if they survive the rape, they may get pregnant and give birth to children with enemy genes. The husband is also victimized. If he survives, he must live with the shame of having been unable to protect.

The perpetrators, I surmise, are also victims. They lose their humanity and are condemned to live with the memory of having committed a horrible crime. I admire the work of psychologist Inger Skjelsbæk (PRIO and University of Oslo), who has interviewed victims and perpetrators of rape in the former Yugoslavia, seeking to understand the psychology and strategy of sexual humiliation.[5]

The same event that Goya depicted two hundred years ago happened again in August 2017 in Myanmar. Soldiers of the national army raped Rohingya women, sometimes in the presence of their husbands. Children fathered by the victims of the Myanmar Army’s appalling tactics now grow up in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

With this in mind, I felt a deep relief and satisfaction when Dennis Mukwege, the Congolese doctor who has dedicated himself to helping victims of war rape, finally received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018. He received it together with Nadia Murad, herself both a survivor and a leading activist in the worldwide struggle against war-related sexual violence. My hope is that the prize will help stimulate their work and struggle in the pursuit of human peace and dignity, regardless of gender, culture or religion.

In 2008, I wrote an essay about the role of civilians in war for an edited volume dedicated to the doyen of Norwegian state feminism, Helga Hernes, on her 70th birthday.[6] As a historian I could not accept the flawed idea of so-called New Wars.[7] The rape and killing of civilians is in no way new. It has persisted through the centuries. Few wars have killed more soldiers than civilians.

In my MA thesis, I wrote a chapter about mass killing through terrorist bombings. Not in Guernica, Dresden or Tokyo but in the Vietnamese port city Haiphong on 23 November 1946. Several thousand civilians were killed by French naval artillery and aerial bombardment that day. I have since visited Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, Hiroshima, Nanjing, Dresden and S-21, the Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh, from which just a few came out alive after the 1975–78 Cambodian genocide. Those few had not yet been put to death when the Vietnamese army arrived to liberate them.

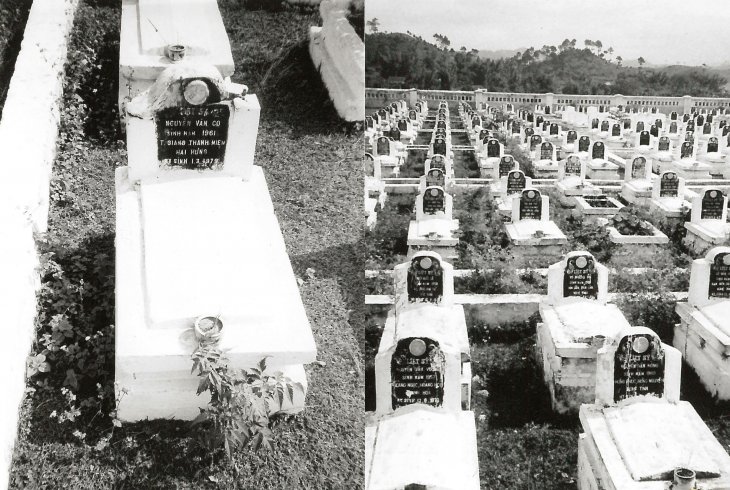

I don’t think I watched one single episode of Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s 2017 TV production The Vietnam War without having to cry. In 1974, I visited the endless rows of graves from the 1941–44 siege of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and in 1989 I saw the long lines of tombs at Cao Bang and Lang Son in Vietnam, dating from the five-week Chinese invasion February–March 1979. I noticed from the birth dates on the graves that everyone was younger than me. Some were as young as my little brother Øyvind Tønnesson, born in 1963. Wars cut off lives in their prime.

Nguyen Van Co was born in 1961. Just like all the other young men in the graves around him, he died on 1 March 1979. Photos from 1989: Stein Tønnesson’s archive

It is meaningful to study and document the horrors of war, the Holocaust, the massacres and genocides. I admire and respect those who do but have not myself ventured far on that painful path. Why, I ask myself, have I missed every opportunity to visit My Lai, where 4–500 unarmed villagers were massacred by Americans in March 1968? Why have I not gone to see the place and meet the survivors? Not because I’m afraid of grief. I do grieve. There is something else I’m afraid of: the political use of victimhood.

My Lai is exploited in Vietnam to show what the Other did to Us. Survivors have made it a profession to weep in front of tourists. I have twice gone through the Museum of American War Crimes in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon). I have seen, but did not like, the Massacre Museum in China’s former capital Nanjing, which displays the crimes of the Japanese “devils” in 1937–38 in gruesome detail but fails to mention how Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of Nationalist China, after having abandoned his capital, decided to blow up dykes so vast farmlands would be flooded and block Japan’s advance. His decision led to the death of at least half a million Chinese peasants, many more than those killed in the Japanese rape of Nanjing.[8]

Japan’s humiliation of China plays a key role in Xi Jinping’s Chinese nationalism today, just as it did in Chiang Kai-shek’s view of history. I’ve seen the cult of victimhood also in Japan. The Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo commemorates the leaders who were “unjustly” tried and executed in 1948.

When Japanese colleagues ask me how long we Japanese must continue to apologize for what our grandparents did in the 1940s, I tell them to stop apologizing and mobilize instead true feelings of remorse: try finding out what led Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Tojo Hideki to commit such crimes against humanity! If a monument were built in central Tokyo to the victims of Japanese militarism, and the Prime Minister would kneel there instead of at the Yasukuni shrine, there would be no more calls for apology.

The claim that the Japanese “rape of Nanjing” in 1937–38 had 300,000 victims plays a key role in contemporary Chinese nationalism. Tønnesson feels uncomfortable when exposed to celebration of victimhood inflicted by another group on one’s own. In the Nanjing Massacre Museum, the Japanese are referred to as “foreign devils.” Photo: X Li / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA

I respect post–Cold War Germany for its peaceful approach to the past. I want to return as often as I can to visit the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. Long quiet paths along rectangular coffins in stone. A Bauhaus graveyard. So simple. So full of mourning.

When Japanese colleagues ask me how long we Japanese must continue to apologize for what our grandparents did in the 1940s, I tell them to stop apologizing and mobilize instead true feelings of remorse: try finding out what led Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Tojo Hideki to commit such crimes against humanity!

In the Spring of 2018, I travelled with a group of friends to Dresden, and was amazed to find that the city’s military museum hardly mentions the British terror bombing of 15–17 February 1945, which cost at least 25,000 lives. A few years back, the museum had a sober and detached exhibition about the destruction and reconstruction of the city, displaying multiple perspectives without taking sides. The permanent exhibition studiously documents Nazi Germany’s war crimes but says almost nothing about the two million German prisoners of war who died in Soviet camps.[9]

Is this a step too far? Might some see it as a parody of self-depreciation? I see a risk of a nationalist backlash and feel convinced by a key argument in novelist Nguyen Viet Thanh’s book Nothing Ever Dies. He claims that “remembering others can simply be a reversal, a mirror, of remembering one’s own, where the other is good and virtuous, and we are bad and flawed”. What he instead looks for is a “just memory” that strives both to remember one’s own and others, while “recalling the weak, the subjugated, the different, … and the forgotten”.[10] At any rate, I cannot help admiring the way Germans have approached their perturbing past.

Tønnesson pays a visit to the Denkmal der Ermordeten Juden Europas whenever he is in Berlin, as a place of meditation and mourning. Photo: Glooh / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA

Third Path: Outbreaks

My third path reaches its end where wars begin. Given their horror, we must continue to study how wars break out. Many have tried. “What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta”, writes Thucydides in The History of the Peloponnesian War.[11] He calls this the “real reason” behind the war, which may be lost if one focuses too much on the immediately preceding events.

Yet, Thucydides does recount those events in much detail. His account shows how some of Athens’ and Sparta’s allies got into conflict with each other and pulled the two main powers into a mutually destructive war that both would have preferred to avoid. Thucydides’ statement about “the real reason” is often referred to in debates about the outbreak of the First World War and about the risk of a confrontation between China (rising Athens) and the USA (fearful Sparta), which could unleash a Third World War.[12]

Thucydides also looks at internal disagreements among decision-makers on either side, particularly in Athens. My own contribution to the history of outbreaks is a study of French and Vietnamese decision-making in 1946, in the run-up to the First Indochina War. When I decided, in 1980, to undertake that study, my hope was to find the origin of the whole cycle of wars in Indochina: The First Indochina War 1946–54, the Second Indochina War 1959–75 (my youth), and the Third Indochina War 1978–89 (which I observed as a concerned historian).

My studies in French, British and American archives led to my MA thesis, supervised by professor Helge Pharo at the University of Oslo, published as a PRIO Report in 1984, revised, extended and translated into French in 1987, then again revised and translated back to English for publication by the University of California Press in 2010, and finally translated and somewhat censored by Vietnam’s Communist Party before publication in Vietnamese in 2013.[13]

My key finding, which remains controversial, is that the outbreak of war in Hanoi on 19 December 1946 was due to a mistake on the part of Vietnam’s communist leaders. The French socialist veteran Léon Blum, who had just formed a transitional government in Paris, wanted badly to avoid war, and did his best to contact President Ho Chi Minh. Ho knew that Blum did not want war and tried to send him telegrams.

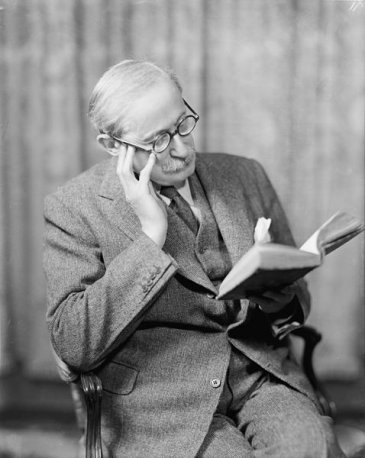

As leader of the French Popular Front government in 1936–37 and 1938, Léon Blum (1872–1950) was forced to watch how the armies of Francisco Franco (1892–1975) destroyed the legitimate government in neighbouring Spain. In December 1946, as leader of a shortlived transition government to the French 4th Republic, Léon Blum shed tears when he was forced to preside over the outbreak of the war in Indochina. Photo: Harris & Ewing Collection / Library of Congress

But the French High Commissioner in Saigon wanted war. He feared that Blum might undermine the French effort to reconquer all of Indochina and create a French-managed federation of five states. The High Commissioner realized that the French government would not allow him to openly take the initiative. Hence, he did his best to provoke the Vietnamese government into action, and he succeeded.

After having faced a series of deliberate French provocations, the Vietnamese army and militia forces (Tu Ve) launched a badly coordinated attack against the French in the evening of 19 December, and the French responded with a well-planned counter-offensive. This is how the First Indochina War began.

President Ho Chi Minh fled to the countryside, where he became a guerrilla leader. Léon Blum, before leaving power to the first constitutional government of the French 4th Republic, could not hold his tears back as he stood in front of a Christmas tree at the headquarters of the French Socialist Party (SFIO) in Paris. In the 1930s, his Popular Front government had been unable to support the Spanish Republic against General Franco, and now – again under his watch – the new French 4th Republic stumbled into a colonial war. It would last eight years, and then came the war in Algeria, which destroyed the French 4th Republic.

In my conclusion, I discussed whether the 19 December outbreak was inevitable or not. I found that it could well have been avoided if Blum and Ho had got in touch or if Ho and Giap had understood that the French High Commissioner was setting a trap for them. However, when I wanted to go further into a counterfactual argument and argue that if only the outbreak had been avoided, then the whole cycle of Indochina Wars might not have happened, I ran into difficulties. The First Indochina War, I realized, would most likely have broken out all the same. Instead of in December 1946, it would have come in the autumn of 1947.

Once the French Communists had been forced out of the French government, the Christian Democrats (MRP) had taken over the presidency of the French cabinet from the Socialists, and the Truman doctrine had singled out communists as the greatest threat to the free world, France would have broken off relations with Ho’s government. So, war would have begun in conjunction with the onset of the Cold War, instead of at a time when the French Communists, Socialists and Christian Democrats were still in government together.

When my mentor and colleague in Australia David G. Marr, with whom I have exchanged manuscripts for forty years, saw my disappointing conclusion, he asked why I had spent so much of my life studying 19 December 1946, if it did not make a greater difference. I have not found a satisfactory answer but would meekly suggest that it may be useful to have a detailed study of how a colonial governor can undermine his government’s policy, and how a young, unproven government can let itself be provoked. For national leaders to avoid war with other nations it is essential that they keep their armies under centralized control. Conflict prevention today depends on President Moon Jae-in of South Korea and Kim Jong Un of North Korea having full control of their governments and armies, and on their ability to play the wild card Trump, whose control of his own government seems shaky.

In Southeast Asia it is a problem that the civilian governments of Thailand, Myanmar and the Philippines have never fully controlled their armies. These three countries are now the only ones in all of East Asia that still have civil wars.

When learning of it in his old age, General Vo Nguyen Giap rejected my contention that something had gone wrong in Vietnamese decision making on 19 December 1946. He gave the order to attack, he claimed, and never regretted it. He had been in full control and the attack was necessary: a failure to respond would have been perceived as a sign of weakness.

In a conversation I had with him, I tried to tell him how much he could have benefitted from showing restraint that night, so Ho Chi Minh could have exposed to the French public the wrongdoings of the French High Commissioner. I also pointed out that his attack, which was meant to be launched simultaneously against all the French garrisons in Vietnam, happened only in Hanoi at the scheduled time, so the French had time to alert their other garrisons and withstand the attacks. I met Giap a few times in the 1990s and 2000s. Afterwards, in his three-volume memoir, he refuted my arguments in writing.[14] I gave my response in my 2010 book, although this part of it was censored in the 2013 Vietnamese version.

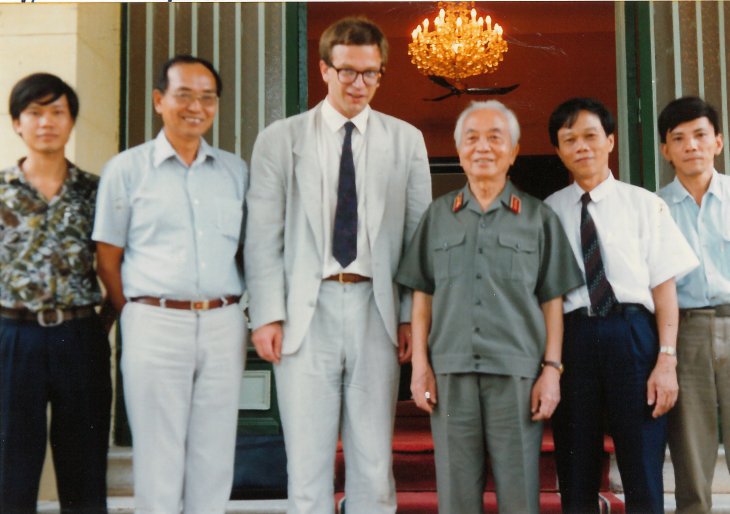

Stein Tønnesson with General Vo Nguyen Giap in Hanoi, 18 September 1992. The young man on the left, Hoang Anh Tuan, attended PRIO’s peace research course at the International Summer School of the University of Oslo, and spent a month at PRIO afterwards, studying the possibility that Vietnam might become a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This did in fact happen in 1995, and today Hoang Anh Tuan serves as Deputy Secretary General of ASEAN in Jakarta. No. 2 from the left is Mr. Nguyen Dinh Vinh, who later became Deputy Director General of Vietnam’s Institute of International Relations (today’s Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam). Photo: Stein Tønnesson’s archive

Eight years after Giap unleashed the First Indochina War, he won his big victory at Dien Bien Phu, at horrendous cost to his people. Giap frightens me. The fact that I have met him personally sometimes makes me shiver. He had so much blood on his hands, and he and I have so much in common. He started out as a history teacher, he read about Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaigns, and as a young man he analyzed class relations in the villages of the Red River Delta. My own first book, in 1976, was a study of the class struggles in the Norwegian woods during the 1920s–30s.[15] He married a Vietnamese historian and authored influential books about the struggles he had been part of.

In 1995, I attended a conference in Hanoi, where Giap met former US Secretary of Defence Robert S. McNamara. The tall and remorseful American wanted to have a real conversation with his short and proud counterpart Giap and learn from him if only one or also a second torpedo had been fired in the Tonkin Gulf incident of August 1964. McNamara assumed, as I did at the time, that Giap had been in command in 1964, in his capacity as Minister of Defence.

We did not know then that Giap had been side-lined by the Communist Party’s new leader Le Duan, and that even President Ho had become a figurehead. Giap disappointed McNamara in 1995 by avoiding a real discussion. Instead, he gave a lecture about the difference between invading another country and resisting an invader.[16]

We now know that Giap actually warned against escalating the communist insurgency in South Vietnam because he feared a full-scale American intervention. He also opposed the Tet offensive in 1968 and the invasion of Cambodia in 1978. The driver of all these fateful acts was Le Duan, who had his political background in the struggle for southern Vietnam.[17] Le Duan died in 1986 but Giap lived until 2013, reaching the age of 102. At the time he passed away, he was known to be critical of the Communist Party leadership. His funeral happened amidst an outpouring of patriotic mourning.

As Giap and McNamara grew old, they both developed more peaceful attitudes. McNamara regretted what he had done when serving as President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Secretary of Defence. Giap did not express regrets, at least not in public. The last time I saw him at his house, he was too frail to recognize me but he read out a message expressing his desire for world peace.

Fourth Path: Severity

My fourth path follows the escalation of a war after its outbreak. Its magnitude or severity may be measured in duration, the number of weapons or troops deployed, the scale of fighting, the number of casualties or the amount of destruction. The great majority of wars are small. Some are severe but only a few are catastrophic. By far the worst ones in the 20th century were the First and the Second World War. Perhaps the most significant event in the 20th century was one that did not happen: the Third World War.

The Vietnam War is the worst of all wars since 1945. It belongs with the Chinese Civil War, the Korean War, the Iran-Iraq war, and the Afghanistan War of the 1980s to a small group with millions or hundreds of thousands of battle deaths. Peace researchers emphasize, however, that small long-lasting wars, like those in Colombia and Myanmar, although they do not include big battles, have devastating consequences for their communities because they involve so much gendered violence, disrupt local economies, prevent economic development, and stimulate criminal production and trade in drugs and other lootable resources.

Another key finding in peace research is that the intensity of fighting in a civil war depends on external aid. The worst that can happen in a civil war is that each side obtains substantial foreign support. As Harvard professor Odd Arne Westad has emphasized, access to assistance from one or the other side in the global Cold War exacerbated the hot civil wars in Third World countries, not least in Indochina.[18]

The end of the Cold War brought a peace dividend by drastically reducing proxy warfare. In the 2010s, however, large-scale external support made a comeback in Ukraine, Syria, Iraq and Yemen. We need to study the effects of proxy warfare and how to prevent the external interventions that widen and prolong civil wars instead of ending them.

I have been thinking about two other factors that tend to escalate wars and increase the death and suffering. If the warring parties have equal strength and end up in a stalemate, they tend to engage in hugely destructive battles. This was the case on the Western front in the First World War, for the Iran-Iraq war from 1980–88, and during the 1998–2000 war between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Yet, stalemated wars between big armies are rare. I believe that another factor has been more fateful. This is the mix of war and revolution. They tend to feed on each other.

By far the two worst wars in the 19th century, in terms of casualties, were the Taiping Wars in China 1850–64 and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in Europe 1792–1815. They ripped societies apart through life-and-death struggles between rebel leaders wanting to totally change the world and traditional kingdoms and principalities. The rebellion leading to the Taiping Wars aimed to create a Heavenly Kingdom on earth and was led by a man who believed himself to be the resurrected Christ.[19]

I do not agree with Steven Pinker and others who say that inter-state wars are more severe than civil wars.[20] The basis for this claim is statistics that categorize wars combining inter-state with intra-state warfare (such as the Thirty Years War, the Napoleonic Wars, the First World War, the Second World War, the Korean War, the Indochina Wars, the Iran-Iraq War, the Afghanistan Wars) only as inter-state. In fact, all those wars and several others either came out of or led to revolutionary civil wars. The most severe wars are those that mix revolution with both civil and inter-state war.

In my doctoral thesis from 1991, I studied how the Vietnamese Revolution grew out of strategic decisions taken in Washington and Tokyo during the Second World War. War led to revolution.[21] In early 1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt gave Japan the impression that he intended to invade Indochina.[22] This prompted Tokyo to launch a coup against the French Indochinese regime, which had survived until then under a July 1941 agreement between the Vichy government and Japan. The coup happened, however, at a time when Japan did not have the capacity to replace the French civilian administration.

The result was a power vacuum, which coincided with a famine taking around half a million lives in north-central Vietnam. The vacuum was filled by Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh league, which until then had led a precarious existence in an area close to the Chinese border. By August 1945, profiting from the power vacuum, local Viet Minh committees had been established all over northern Vietnam. When learning of the Japanese surrender, they seized power so Ho could become president of a new revolutionary republic.

In my study of the subsequent outbreak of war between France and Vietnam, I did not emphasize the fact that the Viet Minh had revolutionary aims that went beyond national independence and unity. Ho insisted that independence and unity would be enough for his life time. Communism could wait. I am not sure if he meant it when he said it.

If France had let Ho Chi Minh run an independent Vietnam, Ho might have become a communist leader who could act independently of Moscow and Beijing – like Josip Broz Tito in Yugoslavia and Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania. Yet it is clear that the Viet Minh leaders did not just fight the French. They also fought rival nationalist factions within the Vietnamese society. During July–October 1946, while Ho was on an official visit to France, Giap, as Deputy Minister of the Interior, organized a wave of repression against non-communist parties.

The mix of multiple lines of conflict – civil wars, US intervention and bombing, massive Chinese and Soviet support for the revolutionary side, and ethnic conflict between Khmer, Viet, Lao and many minorities – made the Vietnam War the most severe of all wars since 1945.

The struggle between communist and non-communist nationalists in Indochina made it possible for France to find local partners in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, and set up so-called Associated States. The Associated State of Vietnam would later become the Republic of (South) Vietnam. The war that the US opted into in the 1960s was thus at once a civil war in South Vietnam, a war between South and North Vietnam, and a war between various factions in Laos and Cambodia.

The mix of multiple lines of conflict – civil wars, US intervention and bombing, massive Chinese and Soviet support for the revolutionary side, and ethnic conflict between Khmer, Viet, Lao and many minorities – made the Vietnam War the most severe of all wars since 1945. And then came the Third Indochina War, which did not just affect Cambodia but also Laos and the border region between Vietnam and China.[23]

In chapters I am writing for the Cambridge History of the Vietnam War and a book about the legacy of revolutions, I will go back to my doctoral thesis and put more emphasis on the role of revolution in driving the cycle of Indochina Wars. In this context, of course, it helps that I am no longer blinded by the admiration I once felt for revolutionary guerrillas.

My brother Johan has reminded me of a question he asked our father, Kåre Tønnesson, a historian of the French Revolution, in 1971 when we were both revolutionary teenagers: “How come you are not a revolutionary when you study revolution?” The answer, which annoyed us at the time but humours us today, was: “Precisely for that reason.”

Fifth Path: Endings

My fifth path looks at how wars come to a close. They may end in victory for one side (as in the First and Second World Wars and in Sri Lanka in 2009), they may peter out as the warring parties cease to fight (as in the Malayan insurgency, which began in 1948 and became inactive long before the insurgent leader Chin Peng capitulated in 1989), or be settled through a formal ceasefire or peace agreement (as between the Indonesian government and the Free Aceh movement in 2005).

There is a debate among peace and conflict researchers about whether victories or peace agreements are most likely to bring lasting peace. This has academic interest but cannot in my view have normative implications. I find it more relevant to compare peace agreements and see why some fail while others succeed.

Many Europeans hoped the First World War would be “the war to end all war”, but the Versailles Treaty of 1920 was not the kind that could create lasting peace. Instead it prepared the ground for the Second World War, and the Middle Eastern Settlement of 1922 provided David Fromkin with the best book title I know from the field of international history: A Peace to End All Peace.[24]

My brother Johan has reminded me of a question he asked our father, Kåre Tønnesson, a historian of the French Revolution, in 1971 when we were both revolutionary teenagers: “How come you are not a revolutionary when you study revolution?” The answer, which annoyed us at the time but humours us today, was: “Precisely for that reason.”

A study I would like to see is a comparison of the five peace agreements that were made for Indochina in the period 1946–91, four of which failed while the last – in my view – succeeded. The first is the one I have studied in detail myself, while the last is the one I would most like to look into now. First France made a deal with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on 6 March 1946, which was reconfirmed in a modus vivendi agreement on 15 September. It collapsed when war broke out on 19 December.

The second agreement was made at a great power conference in Geneva on 21 July 1954. It recognized Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia as independent states, while dividing Vietnam temporarily at the 17th parallel pending national elections to be held before July 1956 in the whole country. The agreement fell apart when the anti-communist nationalist Ngo Dinh Diem took full power in South Vietnam and expelled the French, replacing them with US advisors, who did not consider themselves obliged to fulfil the Geneva agreement. Once it became clear that the agreed elections would not be held, the communist leaders in North Vietnam gradually and hesitantly, and against Soviet as well as Chinese advice, decided to foster a full-scale rebellion in South Vietnam.

The third agreement was made in 1962, again in Geneva, and this time President John F. Kennedy fully endorsed it. The aim was to neutralize Laos. The settlement quickly collapsed as Laotian factions resumed fighting among themselves and the country became a strategic asset for North Vietnam in constructing the “Ho Chi Minh trail” for the transportation of troops, weapons and provisions to the front in South Vietnam.

The fourth agreement was made in Paris January 1973 between the US and North Vietnam (with South Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam as reluctant signatories), after four years of negotiating while fighting. The 1973 Paris agreement made it possible for the US to extricate its troops from Vietnam, but the war did not end. Both sides in the civil war broke the agreement, and just two years after it had been signed (and Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho had been offered the Nobel Peace Prize),[25] a North Vietnamese offensive brought South Vietnam to surrender on 30 April 1975.

The 1973 agreement, which followed extensive American aerial bombing of Cambodia, had the additional effect of weakening the incumbent government in that country and allowing an extremist Cambodian grouping (the Khmer Rouge) to seize Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975, and install a genocidal regime. This in turn led to the Third Indochina War, pitting Vietnam against the Khmer Rouge, which formed a coalition with two other parties, receiving aid from China, Thailand and the USA so it could fight against the Vietnamese occupants and its client regime in Phnom Penh for most of the next decade.

The fifth agreement, about Cambodia, was signed in Paris 1991. It installed a temporary UN administration, set up a coalition government in Phnom Penh, and isolated the Khmer Rouge so it disintegrated and eventually fell apart when its leader Pol Pot died in 1998. Thus, the path was cleared for all three Indochinese countries to establish normal relations with each other and the rest of the world, join the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), launch economic reforms, and obtain rapid growth. The peoples of Indochina have not since seen freedom and democracy, but they live much longer and better lives than their parents and grandparents did.

Sixth Path: Viability

My sixth path, which I alluded to in the beginning, is conceptual: how do we define peace, and what does it take for a peace to be viable?

For a long time, I tried to shy away from this path, where it’s difficult to get through the tangled conceptual undergrowth that hinders understanding. My inclination was to concentrate on empirical studies, look for unknown facts and combine them with the known ones in arguments or narratives geared to sort out case-specific causal connections.

Yet I always also admired conceptual precision. Vague or misleading terms such as “holistic approach” or “root causes” do not appeal to me. I prefer narrow concepts and try to resist the temptation to widen them. Hence, I began to feel that two widely accepted concepts in peace research were mostly leading us astray. As mentioned in the beginning, they are “structural violence” and the distinction between “negative” and “positive” peace. In 2016, I decided to put my criticism of those terms into writing.[26]

Why do I not like the term “structural violence”?

First, because we already have terms to describe social and political systems that harm and shorten people’s lives in other ways than through physical violence: oppression, subjugation, exploitation, tyranny, inequality, discrimination, etc. An unequal or unjust society is not necessarily violent. If we distinguish between violence and injustice, we can study the causal relationship between violence and injustice, and the same goes for inequality: does injustice or inequality lead to more violence or not? We cannot, however, study these relationships if we subsume injustice or inequality under the term violence.

My second reason is political. If we characterize an unjust or unequal but otherwise peaceful society as structurally violent, we make it easy for would-be rebels to legitimize the use of violence against that injustice or inequality. If non-violence is instead appreciated as a virtue in itself, more rebels may opt for non-violent means of struggle.

Peace often depends on threats of violence, within states through repression and between states through deterrence. In such cases, many peace researchers speak of “negative peace”. I see that term as a misnomer. It plays on two different meanings of “negative”. Sometimes the word is used normatively, meaning bad as opposed to good. Sometimes it is used descriptively to denote the absence, as opposed to presence, of a certain condition.

However, when absence of war is called “negative peace” it negates the wrong noun. When a doctor calls a medical test negative, he does not call this “negative health.” A positive test would indicate that the patient is ill. If absence of armed conflict is negative peace, then positive peace must be war, which is absurd. In the same way as a negative test for illness is a positive indication of health, the absence of war is a positive indication of peace. Absence of war is thus positive peace.

Yet such a positive peace may be frail or insecure. What peace researchers normally mean when they call for a “positive peace” is that there should not just be absence of armed conflict but something more, like justice or equality. Hence, they feel a need to build justice or equality into their definition of peace. This is where they go wrong and distort our concepts. Fortunately, there is now a tendency to abandon the terms negative/positive peace. Peace researchers speak instead of shallow/deep, low quality/high quality, resilient/non-resilient, sustainable/unsustainable, or nonviable/viable peace.

This means that the peace-war dichotomy can be understood as a continuum with total war on one side and viable peace on the other, and with the absence of war (or violence) representing a dividing line between the peaceful and unpeaceful side of the continuum. What makes peace viable is of course a key concern in peace research.[27]

In defining the difference between viable and less viable conditions of peace, I have sought inspiration from Karl Deutsch’s classic concept of a security community. He defined it as a group of people with a sense of community and “institutions and practices strong enough and widespread enough to assure for a ‘long’ time, dependable expectations of ‘peaceful change’ among its population”.

Such communities can exist within just one state or within a territory consisting of several states.[28] Deutsch also spoke of a no-war community. While members of a no-war community keep up a military preparedness to defend themselves against each other, although they see little risk that they may have to resort to force, the inhabitants of a security community take peace so much for granted that they no longer see a need to arm against one another. A security community has viable peace.

Seventh Path: Regional Transitions

The seventh path is one I discovered only after the turn of the millennium. I had never studied statistics myself and had long found it boring. However, my exposure to quantitative peace research at PRIO and as a member of the editorial board of the Journal or Peace Research led me to appreciate statistical studies. I was intrigued by an article written by the Finnish peace researcher Timo Kivimäki, trying to explain how Southeast Asia had overcome its wars and become so much more peaceful than before.

We met and decided to cooperate, and eventually developed a research proposal together with Isak Svensson of Uppsala University. Our aim was to explain a statistical transition to peace in a major world region with more than 30% of the world’s population. This is East Asia (Northeast + Southeast Asia), which suffered 80% of all the world’s estimated battle deaths during 1946–79, but only 6% in the 1980s, and in the years 1991–2017 less than 2%.[29] How come?

The statistical finding that formed the basis for our research proposal depended on a narrow definition of peace as (relative) absence of armed conflict. Yet the research programme we developed, after receiving generous funding from the Swedish Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, included several researchers who questioned such narrow concepts. They investigated the many shortcomings of the East Asian peace as far as quality or viability are concerned.

It was clear from the outset that the East Asian Peace cannot be called either a “security community” or a “no-war community” but remains fragile with nations arming against each other, threatening each other, and making operational plans for war. Many of the regional governments are moreover authoritarian or outright dictatorial. Yet I see the East Asian Peace as representing a momentous improvement from the foregoing period. East Asia’s transition from widespread and frequent warfare from 1840–1979 to four decades of relative peace has allowed for an astounding improvement of people’s lives.

In our programme, we explored several competing theories to explain the regional transition. I developed, together with Kivimäki,[30] a “developmental peace” theory. In my view, the regional peace came about as a cumulative effect of a series of national priority shifts at different junctures. In one country after the other, the governing elite decided to shift from various kinds of ideological or irredentist priorities to aiming for state-driven economic growth: Japan 1945–46, South Korea 1961, Indonesia and Singapore 1965, Taiwan 1972, China 1978–79, Malaysia 1984, Vietnam 1986, Laos and Cambodia in the 1990s.

[T]he regional peace came about as a cumulative effect of a series of national priority shifts at different junctures. In one country after the other, the governing elite decided to shift from various kinds of ideological or irredentist priorities to aiming for state-driven economic growth

In each case, leaders emphasizing economic growth sought and obtained stability both externally and internally. Then peace followed. In 2018, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un organized a dramatic rapprochement with South Korea, the USA and China in an apparent attempt to join the East Asian zone of prosperity (while probably intending to keep his nuclear weapons).[31] The East Asian Peace is not a high-quality peace from either a liberal or a socialist point of view. It is repressive and allows for appalling inequalities. Yet it has allowed an astounding economic growth. Life expectancy at birth has risen dramatically in every single East Asian country, and, as Alex Bellamy has shown it has also led to a dramatic decrease in “mass atrocities”.[32] East Asia’s economic rise has depended on peace.

As someone interested in global history, I suggest that we make more comparisons of geographical regions with regard to levels of armed conflict, and ask questions like: how could East Asia make a transition from the world’s main battlefield to a region of peace and prosperity, while the Middle East remains mired in chaos and war? Why have Latin America and Africa had their share of devastating civil wars but very few inter-state wars?

Eighth Path: Peace Practices

The eighth path is practical. How can we characterize peaceful communication? Human interaction is of course mostly peaceful. What people do to each other, even in times of war, is peaceful most of the time. Violent events are exceptional. This is easy to forget. Researchers, even peace researchers, are drawn to studying outbreaks of violence without paying attention to the peaceful interaction that happens in-between.

I feel inspired by my colleague at PRIO Wenche Hauge, who has compared violent and peaceful communities in Haiti, trying to find out what made some communities avoid violence while others succumbed to it. She finds that institutionalized patterns of cooperation, often with informal but well-known lines of authority, have helped communities retain their internal peace. She made a similar study in Madagascar, and found there too that established institutions cutting across ethnic divides prevented disputes from being used by political rivals to whip up hostile communal sentiments.[33]

Her research conclusions remind me of findings by the Norwegian anthropologist Thomas Hylland Eriksen, whose doctoral thesis was a study of peaceful multi-ethnic societies in Mauritius and Trinidad.[34] I have been inspired by their findings, and also by peace practices I have observed in the field, and the activities organized by local and international NGOs seeking to transfer lessons learned from one place to another. Even in the worst of situations, there are people who cooperate peacefully across ethnic divides.

Wenche Hauge (1959–), photo: PRIO; Thomas Hylland Eriksen (1962–), photo: GAD / Wikimedia Commons; and Eva Østbye (1960–), photo: Collaborative Learning Projects (CDA)

In Myanmar, I have had a chance to learn from the training activities of the RAFT organization, led by the Norwegian historian and practitioner Eva Østbye. Following the principles of “do no harm” and “conflict sensitivity” as defined by Mary B. Andersson, this Myanmar based organization seeks to train public institutions, private companies and organizations in how to map out local patterns of conflict and cooperation, reflecting local “dividers” and “connectors,” as an essential phase in any planning of investments or other interventions. The aim is to prevent violent conflict and build peace.

In 2017, I stepped down from my East Asian macro approach and began working on three micro studies of interaction among ethnic armed groups and government agencies in Myanmar. I want to find out why in some places and on some occasions, people with different ethnic identities treat each other with decency and respect, while in other instances they commit heinous crimes against each other.

My research partner is the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security (MIPS). We study how ethnic armed organizations influence each other when choosing to either fight or agree to a ceasefire, and how peaceful and violent interactions are reflected in the social media.

Could the recent massive introduction of smartphones in Myanmar provide a platform not just for hate speech and violent mobilization but also for peaceful interaction across ethnic and religious boundaries?

Together with MIPS and PhD student Julie Marie Hansen at PRIO I look for differences in the way men and women use their smartphones. Myanmar is a country where people who did not have access to any kind of phone or computer until recently can suddenly communicate with anyone in the whole world.

Changes in communication patterns that have taken decades in other countries have come to Myanmar in just four to five years, in a context of ongoing armed conflicts. I want to consider the potential of social media to develop peaceful practices in a society that has not yet joined the East Asian Peace.

Could the recent massive introduction of smartphones in Myanmar provide a platform not just for hate speech and violent mobilization but also for peaceful interaction across ethnic and religious boundaries?

Some would not see this as history. I do. I find it impossible to grasp anything called “the present”. Historians study the past, which includes everything that has happened until this moment. I conceive of “the present” as a constantly moving dividing line between past and future. We form the future based on what we know about the past.

This is my rationale for having chosen to concentrate, as a peace historian, on recent history. It is the most recent history that has the strongest impact on the future. Peace practices have, however, existed throughout known history, and comparisons of such practices over time, under different economic, technological and cultural conditions, should be further emphasized in peace research.

Ninth Path: Minor Utopias

My ninth path moves ahead of the others by looking at plans, visions or goals. At some points in history, new constellations of power and influence give radical reformers a chance to change the world for the better. These are, to borrow the expression of Jay Winter, “utopian moments”.[35]

They resemble what I referred to above as national priority shifts, but Winter’s moments are international. He does not look at “major utopias” such as Paradise on Earth, a Harmonious World or a Classless Society but at “minor”, more practical utopias. One utopian moment was in 1948, when René Cassin became the key node in an international network of reformers, who seized upon a chance they got before the full onset of the Cold War and obtained the adoption of a Universal Declaration of Human Rights. What an achievement!

I feel inspired by Winter, and would like to nominate another “minor utopia”, namely the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which has become a global constitution for the oceans. The 1970s, with its quest for a new world economic order, with China’s entry into the United Nations, and US-Chinese and US-Soviet détente, provided the momentum that was needed to move forward with arms control and other international treaties.

I see the Law of the Sea Convention as a huge step in the direction of global peace. This is not because it provided fairness and equality between nations or removed all territorial conflict. The Law of the Sea Convention privileges states with many islands or long coasts (such as the USA, France, Chile, Argentina, Angola and Norway) by giving them sovereign rights to the resources in the water and under the seabed in a huge 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone. Coastal states in Latin America and Africa played key roles in pushing for that part of the Convention.

The main reason why I see the Law of the Sea Convention as a huge achievement for peace is that it sets geographical distance – not history or effective jurisdiction – as the basis for delimiting national zones. To the extent that the geographic principle is accepted, the scope of territorial conflict is drastically reduced. It does not, as on land, depend on power or territorial control but on purely geographic measurement.[36]

The main reason why I see the Law of the Sea Convention as a huge achievement for peace is that it sets geographical distance – not history or effective jurisdiction – as the basis for delimiting national zones.

Legitimate disputes can only arise in those areas where disputed islands may generate a right to an Exclusive Economic Zone of their own and thus create overlapping claims. Other disputes may be resolved through the application of established principles for how to calculate median lines, with room for just a little give-and-take. From 1999–2000, the Convention made it possible for Vietnam and China to delimit their territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zones in the Gulf of Tonkin, and also agree on a fishing agreement.[37] In 2010, the Law of the Sea Convention allowed Norway and Russia, after thirty years of negotiation, to sign a delimitation treaty in the Barents Sea.

Stein Tønnesson attends a conference with Indonesian ambassador Hasjim Djalal (1934–), Indonesia’s leading expert on the Law of the Sea, who later hosted a number of Managing Potential Conflict in the South China Sea workshops in Indonesia. Photo: Stein Tønnesson’s archive.

The Law of the Sea Convention also includes another fundamental achievement for world peace. It established the principle that the resources in “the Area” (meaning the seabed under the High Seas, outside of 200 nautical miles from all coasts) is the global heritage of mankind. Any exploitation of resources in the Area shall be reported to and taxed by the United Nations.

Unfortunately, the world’s two greatest powers refuse to accept basic aspects of the Law of the Sea Convention. The US is against the principle of the global heritage of mankind, insists on a free-for-all principle, and will not accept any global “socialist” tax. This is the main reason why the US Senate has not ratified the treaty.

China accepts the rules on The Area and pays taxes to the UN for its exploitation of deep sea resources. In 1996, the Chinese National People’s Congress also ratified the Convention. However, China does not in practice accept the basic principle that maritime zones can only be claimed on the basis of geographical distance from coasts. Unfortunately, the South China Sea, with its immense importance for world shipping, strategic role for the Chinese, US, and Japanese navies, symbolic role in Chinese patriotic imagining, and dwindling fish stocks due to weak or non-existing resource management, is a place where the capacity of disputed islands to generate maritime zones makes it hard to resolve maritime disputes.

An Arbitration Tribunal under the Law of the Sea Convention, established at the initiative of the Philippines, sought to clarify the most difficult issues in a 2016 ruling.[38] However, China refused to fulfil its obligation under the treaty to take part in the arbitration, and totally refuted the Tribunal’s award. In contravention of the geographic principle, China insists that it has historical rights in virtually the whole of the South China Sea, including waters close to other countries’ shores. China thus treats the sea as if it were land. In so doing, it breaks with the fundamental principle in international law that “land dominates the sea”, and fosters doubts about its respect for international law in general. This is a major problem not only for peace in East Asia but for peace worldwide, since it also affects China-US relations.

I have been trying to persuade Chinese colleagues that they can reach satisfactory solutions for their country, based on a loyal interpretation of the Law of the Sea, which is quite flexible, but have mostly spoken to deaf ears.

Utopian moments have allowed the creation of peace-enhancing treaties and institutions, constituting what Winter calls “minor utopias”, but they fall apart again if major powers decide to ignore or reject what has been solemnly agreed.

Conclusion

A possible tenth historical path, which I have not pursued although I flirted with it in my youth, is major utopias. Many movements in history have rejected all incumbent institutions or beliefs and have sought to create a new and shining society, based on justice, harmony and peace.

What I call the East Asian Peace, a relative absence of warfare in East Asia since the 1980s, is not a utopia but a historical reality. For a long time, East Asia has seen very little war. Yet the East Asian Peace is just a minimal or fragile peace since so many conflicts have been left unresolved. There is a constant risk of new outbreaks. Yet I think the war avoidance we have witnessed for three-to-four decades, is already a positive achievement, providing a basis for further strides toward a more viable peace.

In my youth, I was moderately fascinated by major utopias. In 1971, I wrote a school essay about Thomas Moore’s Utopia. I seem to remember that already then, inspired by my father’s cool rationality, I thought of major utopias as ideals that would never be totally fulfilled. I was not much attracted to the idea of absolute peace. I never liked the idea of Paradise and did not even believe in the possibility of a classless society, although I sometimes held it out as a beacon to strive towards.

More recently, I was deeply sceptical when China’s former leader Hu Jintao promoted the idea of a Harmonious Society. My fear was that China might use violence to defend harmony, as indeed it is doing domestically through various kinds of repression. Peace for a peace researcher is not harmony but non-violent management of conflict and non-violent struggle (ahimsa).

Visions of a total eternal peace have inspired ideological leaders and movements worldwide. Major utopias have also sometimes brought genuinely peaceful achievements. Yet they have more often provided legitimacy to human rights abuse and horrible crimes. Just like Jay Winter, I’m weary of beliefs in total peace or harmony. I have lost my faith in revolutionary change but feel inspired when regions or nations reform and turn more peaceful, and when new, innovative solutions are found to longstanding disputes. I would like to see historians do more comparisons between peaceful and violent communities.

To sum up, among my nine paths, the first (war as war) is dubious but necessary. The second (war as horror) is admirable provided it does not denounce “others” for what they did to “us” but instead helps create a just memory. The third (outbreak), fourth (severity) and fifth (endings) are classics that need to be kept alive. The sixth (viability or peace building) is fortunately a growing field of study. The seventh (regional transitions), the eighth (peace practices) and the ninth (utopian moments) are the ones I would like to pursue in the rest of my peace researching life.