Elizaveta Gaufman, Security Threats and Public Perception: Digital Russia and the Ukraine Crisis, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, 222 pp.: 9783319432007 (hbk)

Book Review by Bohdana Kurylo

The transformation of the Russian state under the presidency of Vladimir Putin, which has culminated in the current crisis in Ukraine, has been of great interest to security studies scholars. Hence, it is surprising that inquiry into Russia’s security politics has mostly remained the domain of neorealist approaches. In this light, Elizaveta Gaufman’s book, Security Threats and Public Perception: Digital Russia and The Ukraine Crisis, is a welcome contribution. The question that guides Gaufman’s inquiry, which reflects a concern shared by other second-generation securitisation scholars, asks: ‘under what conditions are threat narratives successful?’ (p. 4). In other words, what types of threat-framing are most likely to lead the audience to accept a specific threat construct?

Gaufman argues that the securitising move is successful if it is grounded in an existential threat and personification, whereby the threat is attached to an individual or a group. Importantly, the threat narrative must resonate with previous threat constructs, which are stored in the collective memory, and be broadcasted on the governmental level. Gaufman uses Halbwachs’ (1980) concept of collective memory to refer to a ‘shared pool of information held in the memories of two or more members of a group’. Given that the audience at stake is the general public, looking at social network discourses- or digital memory- was helpful for investigating whether the official discourse had gained support at the grass-roots level.

..Gaufman goes beyond securitisation theory’s narrow fixation on the adoption of extraordinary measures in order to ascertain the ‘success’ of a securitising act. Instead, the author shows that audience response can be a more precise indicator of successful securitisation..

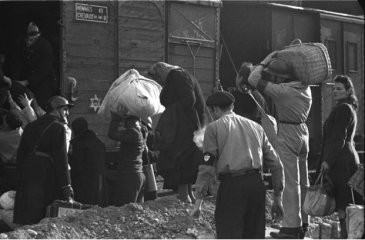

Apart from securitisation theory, the book combines enemy image research and memory studies to analyse threat narratives in Putin’s Russia. The presence of ‘the Ukraine crisis’ in the book’s title is rather misleading as it informs only one chapter. In fact, the book’s horizon is much broader, giving equal attention to at least five more different threat narratives. Having established its theoretical framework and methodology in chapters 1-4, the book moves on to discuss threat narratives with regard to the USA; fascism discourse in relation to the Ukraine crisis; Russia’s ‘spiritual bonds’; homosexuality; migration; and a cluster of specious non-existential ‘threats’, such as China and Russia’s Jewish population.

Gaufman goes beyond securitisation theory’s narrow fixation on the adoption of extraordinary measures in order to ascertain the ‘success’ of a securitising act. Instead, the author shows that audience response can be a more precise indicator of successful securitisation. In other words, the securitising move is successful provided that the audience re-articulates and co-constructs the threat narrative. Conceptualising the embeddedness of threat narratives at the audience level helps problematise the notion of the audience, addressing a major theoretical and methodological limitation of securitisation theory. Highlighting the importance of collective memory reveals the significance of the audience as a securitisation actor, whose role is usually hidden behind the speech of the securitiser. The book’s significant discovery is that the very authority to define the threat belongs to the audience ‘because it is the level to which prejudice is consigned’ (p. 40). Even in authoritarian contexts, such as Russia, the official security discourse ‘needs to be congruent with what society has to say about security’ (p. 21).

Gaufman also makes an interesting point that securitisation can be represented in the form of a spiral, originating from a speech act and culminating into extraordinary measures. The latter can, in turn, initiate another cycle of threat construction. In so doing, securitisation can be self-perpetuating and consist of multiple cycles. The idea implies that securitisation processes are more complex than usually conceived, but the author does not develop it further. Nonetheless, precisely this idea could allow the analysis to go deeper by uncovering the continuity and change of securitisation as a historical process.

As such, rather than being seen as a recent development initiated by Putin, securitisation related to the Ukraine crisis can be seen as just one of the many cycles of securitisation that have occurred through the centuries. For example, the perception of the Euromaidan as a fascist movement is essentially based on the original construction of fascism as a security issue. It might be that the resulting collective memory also functions as a binding force that makes securitisation a continuous process in history, albeit periodically dormant. Consequently, focusing predominantly on Putin’s Russia captures only one cycle of securitisation. A stronger historical perspective dissecting the continuity of securitisation could complement the book’s empirical findings. This would require concentrating on fewer case studies instead of trying to cover so many at the expense of their depth.

Furthermore, the book only briefly mentions the notion of mnemonic security – ‘protecting a certain flow of historical narratives’ – stating that it can function as a legitimation strategy (p. 6). Arguably, more attention could have been given to how securitisation may be used in the service of mnemonic security. The latter can be vital for salvaging society’s recognition of the sovereign as sovereign, especially when it comes to Putin’s Russia (Heath-Kelly, 2016). In other words, can securitisation be initiated in order to rewrite memory rather than memory be used to legitimise securitisation?

While addressing these sorts of questions would have strengthened the book’s contribution, it nevertheless offers a framework of analysis that can be applied to various threat narratives in democratic and non-democratic contexts alike. Bringing collective memory into the study of securitisation shows the need to understand the culture-specific embeddedness of threat constructs, as opposed to the many de-contextualised analyses of securitisation. Future research might consider expanding this framework beyond the focus on threats. One might analyse how collective memory impacts the construction of the referent object, the responses of the audience, security measures and the very meaning of security. Ultimately, given its security focus, this review cannot do justice to the book’s vast contribution to the fields of Russian politics, memory studies and digital humanities, which deserves a separate discussion.

References:

Halbwachs, M., 1980. The Collective Memory. New York: Harper & Row Colophon.

Heath-Kelly, C., 2016. Death and Security: Memory and Mortality at the Bombsite. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

If your child comes home from school and tells you they participated in an obstacle course with some soldiers in P.E. class, should you be worried that their

If your child comes home from school and tells you they participated in an obstacle course with some soldiers in P.E. class, should you be worried that their