Why do satirists and critics of religion have to be so provocative? Why must they publish images that they know to be offensive to some people’s beliefs and traditions – and that brutal extremists may use as a pretext for terrorist acts?

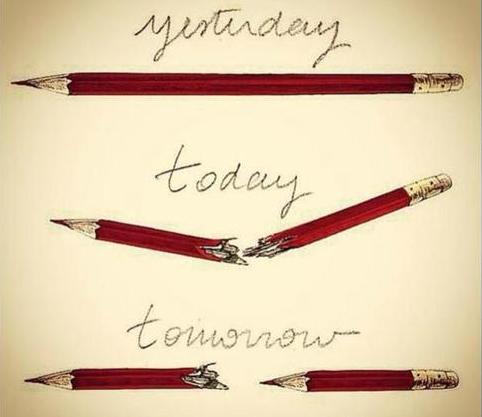

Illustrator Lucille Clerc, via Twitter (@LucilleClerc)

That such questions are asked is understandable. But for many reasons they must be answered with a solid defence of the freedom of expression.

In the wake of the terrorist acts in Paris, let us take a moment to remind ourselves of some of the most important reasons why this is so:

The backbone of a free society

Firstly: The ability to criticize religions and ideologies is a central component of a free society.

That is not to defend the validity of all criticisms of religion. Malicious attacks throughout history on Judaism, which have often been characterized as attacks on a powerful elite, are an all too clear reminder of this fact. Many other examples, contemporary and historical, can be added.

But nonetheless, the moment we declare that certain beliefs are off limits for public criticism – either in print or in speech – is the moment that we put an end to true freedom of expression, belief and thought.

This is because your beliefs – or mine – may be next on the list for prohibition. After all, what is blasphemous to one person will often be an article of faith to another. Therefore, the legal space, even for that which we react against ethically, must be open and secure.

A high threshold for satire

Secondly: We must apply an especially high threshold for satire. By its very nature, satire provokes and will sometimes deeply offend.

By all means, not all satire is worthy or appropriate. Seen from the perspective of ethics, or simply of generally acceptable behaviour, some satire is crude and unnecessarily offensive. To use an example: Suppose that the topic of our discussion here was satire that lampooned categories of people such as women or homosexuals. Would we insist that editors should publish more such satire, and that it would be cowardly to fail to do so due to fears of the potential reaction? Scarcely so.

But all the same, attempts to gag satire – whether by legal means or by threats of violence – will mean that we will lose that vital channel for freedom that disrespectful satire represents.

Polite and compliant satirists, who stick to clear limits regarding the targets of their lampooning, are every authoritarian leader’s dream.

Live with differences, including religious differences

Thirdly: Yes, of course it is acceptable to respond to assertions that one finds hurtful or offensive. It is acceptable to believe that images of the Prophet Muhammad are sacrilegious.

But one’s response should be limited to the weapons of the satirists, journalists and editors themselves: words and images.

Threats, killings and other forms of de facto suffocation of opinions are illegal, outrageous and unworthy – and moreover conflict with the interests of every religion and system of belief.

Hence, we must learn to live with differences, including differences about holiness and religion, and to address them through heated exchanges of opinion, not through violence, punishment or intimidation.

Publication entails responsibility

Fourthly: It is acceptable for an editor or publisher to believe that something should not be said or published because it may offend. Editors make such decisions everyday.

Publishing an opinion entails responsibility. For example, I must take responsibility for what I am writing here.

But this concept of responsibility cannot be used to suggest that I should take responsibility for other people’s use of my opinions to justify violence and brutality – assuming that I myself have not directly encouraged the use of violent means. Such an extension of the concept of responsibility is clearly unacceptable.

For these reasons we must never cease to protect the rights and safety of people who provoke and challenge – of those whose boundaries for what is acceptable may be different from one’s own.

Their freedom of expression must remain secure, for only then can democracy be secure.

This text was published in Norwegian in Aftenposten 12 January: Etter Charlie Hebdo: Vi må aldri slutte å slå ring om rettighetene til dem som provoserer og utfordrer

Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext