New media, new content

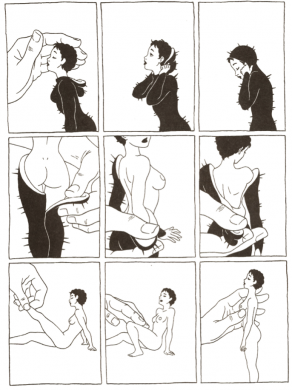

Reem: “Thorn,” Tuk-Tuk 7, pp. 37. Tuk-Tuk is a bi-monthly independent magazine run by a collective of young artists.

Warning: This is all work in progress, so it leaves much to be desired. But this subject is so fun working on that I wanted to share what I have even if it is still pretty undeveloped. OK, here goes:

During the last few years, the literary scene in Egypt has been enriched by a new kind of medium: Comics for grown-ups. Arab comics for grown-ups is a new cultural phenomenon which is only now beginning to attract attention, not least thanks to the efforts of Marcia Lynx Qualey, and it provides a rich, fun and stimulating window into contemporary Arab culture. In the course of a few years, we have seen manga-inspired horror stories, crime noir set in Cairo, and anthologies with stories ranging from the funny and surreal to deeply disturbing accounts of poverty and oppression. The most visible venue for the new comics is Tuk-Tuk, a bi-monthly independent magazine run by a collective of young artists.

Reem: “Thorn,” Tuk-Tuk 7, pp. 38

Comics as such is of course not new to Egypt. There is a decades-long tradition of comics magazines for children in the country, like Samir, and some of the strips in these magazines are very sophisticated and may speak to adults as well as children. But the phenomenon I am writing about here is independent comics for grown-ups, with content of a nature that has necessitated “for grown-ups only” stickers on the cover. This arguably started with the publication in 2008 of Metro, Egypt’s first graphic novel, written by Magdi al-Shafi’i. Metro is a piece of noir fiction about a young computer programmer who robs a bank in desperation as the system prevents him from making it, filled as it is with corruption and crime.

In the year before and after the revolution, there was an intense blossoming of other kinds of comics, and in fact a publishing house dedicated to comics was recently established. These comics span a wide range of themes, styles. Many of them are not political at all, but just for entertainment.

But there is also a discernible tendency towards critique, whether it is couched in humorous or more serious terms, and this is what concerns me here. In particular, I want to comment on how comics may be a channel for criticizing patriarchal authoritarianism of Egypt, prominent before the revolution and resurfacing after it. Many of the artistic expressions during the revolution shared the same critical bent. One of the founders of Tuk-Tuk and a central figure on the Egyptian comics scene, Mohammed Shennawy, expressed the dual socio-political and artistic aims of Tuk-Tuk:

“We wanted to make stories, not only cartoons, for grown-ups, and light stories in ‘ammiyya about real issues in the street, not educational stuff. Also we wanted to export an Egyptian way of drawing. (…) And it would contain themes relating to government, to the family, all the traditions, the taboos, the clichés, we are against all that.”

Read more at The New Middle East Blog, where the full text was published 17 April 2015.