Imagine being at a dinner party with friends. Some you know from before and some are new to you. You are served a welcome drink, smile, and begin to greet the other guests. The conversation starts amicably with exchanges about the weather, where you are from, recent events and perhaps your connections to the host or hostess. After initial pleasantries have been exhausted, the conversation turns to lines of work. One guest might work in insurance, his spouse could be an engineer and their friends, the hosts, might be teachers and writers. A few new guests join your conversation which then moves to schools and the state of the roads in the city. Then the insurance guy tells a surreal story about an insurance fraud case he has just recently worked on. Everybody laughs, spirits are high, and then the smiling crowd suddenly turns to you and the inevitable question is asked: So what do you do? Imagine that you are me in this setting.

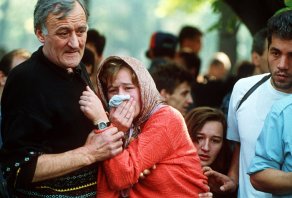

My job, and research focus, are not dinner-party or small-talk material… Funeral during the siege of Sarajevo in 1992. Photo: Mikhail Evstafiev – Mikhail Evstafiev. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is the moment to take stock of my audience quickly and accurately, because the rest of the evening hinges on my answer. Is this a crowd where the answer should be “I am a researcher,” suggesting a kind of generic occupation, perhaps evoking images of a scholarly detective equipped with methodological and theoretical knowledge to tackle the undiscovered? In such a case, the remainder of the evening will entail discussions about science and research. Or is this a crowd where I can go a little further and say “I am a peace researcher”, which inevitably turns any conversation into a sombre discussion of world affairs, in which men turn talkative and women turn silent. Or is it the kind of crowd where I can talk about what I really do? Can I utter the following explicit sentence: “I am a researcher in psychology focusing on crimes of sexual violence in war?” What is at risk if I do? How will the evening unfold after a confession like that?

I have been in this situation many times. I have tried all sorts of different responses, but when opting for the explicit confession, a series of likely and possible outcomes follow. My occupational confession always seems to elicit awkward silences and odd glances. People look at me as though I am tainted by the stigma associated with the subject-matter that I study. Most people turn awkward, unsure as to how to respond. Is a joke in order? Or is the appropriate response to seem even more concerned, not just about the state of world affairs, but about humanity itself? Many conversationalists pause and suddenly realize their drink is empty and needs refilling, or look around in order to plan another means of escape. Maybe they themselves also feel tainted by the stigma attached to the crimes and hence take evasive action. Clearly, and not surprisingly, my job, and research focus, are not dinner-party or small-talk material.

I have researched crimes of sexual violence in war for more than 15 years. I fine tune my social conversations because of my work and how it affects me. I do this as a way of stifling my urge to scream out about the horrors I have studied and attempted to understand. Realizing what impact an outcry might have on others, and me, I hold back and resist the temptation to be loud. Instead I write, quietly and with pain, about what I find out. I try to transform the insights into academic language and format, in order to reach audiences who can take in the message, and whose urge is not to hide and run for cover. I wish to reach audiences who need to listen, and who are paid to listen, fellow academics and policymakers. This is my job, I could have said that at the dinner party — yet I seldom do.

When my research focused on the lives of survivors of crimes of sexual violence things were somewhat easier. For my listeners I became the outlet for their empathy with the victims and horror at the loss, grief and trauma the victims had experienced. I could often find myself overwhelmed with sympathy and admiration – not for me as a person but for the resilience and survival of the victims, which I described. I experienced this victim-oriented research as rewarding and important. Switching the focus to perpetrators of the same crimes has not evoked the same reaction and has proved much more difficult to tackle — on several levels.

Norwegian guidelines for researchers in the social sciences, law and the humanities ask the researcher to “show respect for the values and views of research subjects, even if they differ from those generally accepted by society at large. Researchers should not ascribe irrational or unworthy motives to anyone without providing convincing arguments for doing so”. How could I apply this guideline to the study of perpetrators after having studied the victims of their crimes? Would it be unethical for me to try to understand the mindsets of the perpetrators? Further, could it be seen as a betrayal vis-à-vis the victims? Would I be stigmatized for even showing an interest in the perpetrators’ world views?

Not dinner-party or small-talk material… “Karaman’s House”, a location where women were tortured and raped near Foča, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photograph provided courtesy of the ICTY

Crimes of sexual violence are a problem for society because far too many men commit such crimes. Without perpetrators, of course, there are no victims. Having this understanding as a starting point, I decided I wanted to study perpetrators as a class, not individually. I did not wish to enter the perpetrator’s worlds and investigate their values and views, but I still wanted to find out about the thinking surrounding the perpetrator’s crimes. Getting to an understanding of what possessed them to commit such acts in the midst of chaos, fear and violence was, in my view, important. Were they ordered to do these things or were they acting out of their free will? Did they see their behaviour as sex or violence? What would they say if they were asked to explain? Since I could not ask my questions directly to the perpetrators themselves, where could I turn?

The answer was the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). This court has asked a number of significant perpetrators to explain publicly what they have done. In the ICTY court the perpetrators were being held accountable and their stories were scrutinized and weighed. Eventually the individuals in question were found guilty and sentenced. The court has asked principal perpetrators whether they considered their actions as taken in furtherance of their military goals, or as leisure activities? What would they say in their defence regarding these acts? What were their explanations and excuses? Numerous transcripts with lawyers, victims, witnesses and perpetrators reveal new insights about the criminals and their crimes. Stories about military behaviours unfolded in the courtroom where narratives of normality and abnormality were convoluted. The audience was, and is, a world that has come to adopt new norms and reactions to these crimes, norms that resist the notion that these acts are normal in war, that they are collateral damage and unavoidable.

What the studies of the ICTY’s dealings with perpetrators of sexual violence crimes have shown, above all, is that the legal process also results in stigma transference. By bringing these crimes and the perpetrators to court, the stigma normally attached to the victims is slowly, but inevitably, transferred to the perpetrators. In the courtroom, far more victims than expected were able to hold their heads high, tell their stories and place the blame on the perpetrators, while the perpetrators looked down, refused to talk or occasionally admitted and apologized for their actions. A new normative order has evolved – and with some luck this will have a deterrent effect on future potential perpetrators.

At my next dinner party, this is the story I will tell. That is, if anyone still wants to listen. Or, maybe I’ll just say that I am deputy director at a research institute, and write an article about my research instead…

- For further reading, here is Skjelsbæk’s article “The Military Perpetrator: A Narrative Analysis of Sentencing Judgments on Sexual Violence Offenders at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY)“, recently published in Journal of Social and Political Psychology.

[…] http://blogs.prio.org/2015/04/tainted-by-stigma/ […]