In making the choice between pessimism and optimism, it may be a risky business to lean on everyday news. Let us rather have a look at figures that reveal more long-term tendencies.

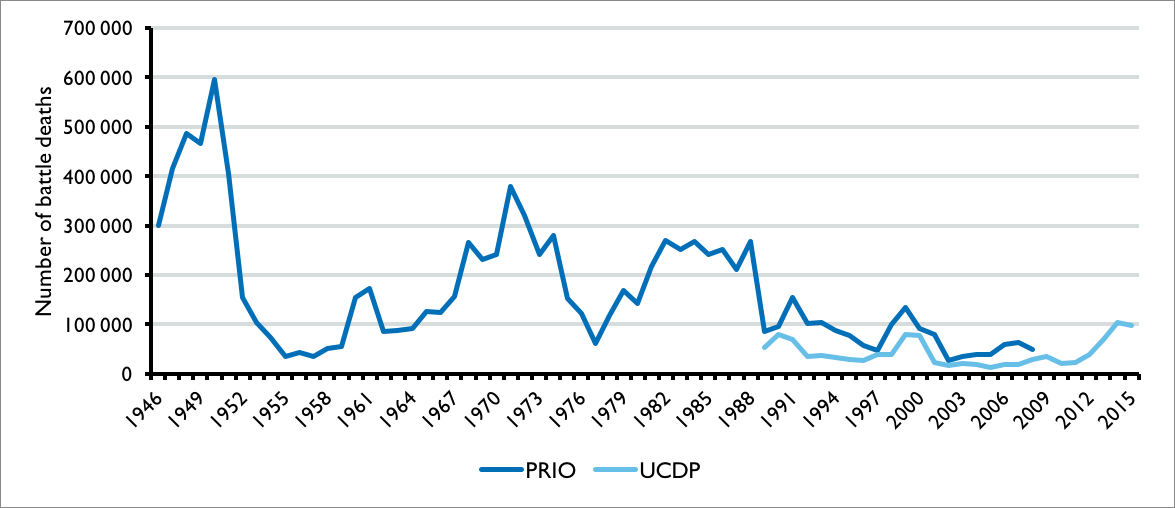

PRIO: Data from the Peace Research Institute Oslo. UCDP: Data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program

Steven Pinker’s book The Better Angels of Our Nature, published in 2011, painted an optimistic picture of mankind emerging from its violent past. Since then, however, the trend has gone in the wrong direction. My work on a book in Norwegian on the same topic has been conducted during this reversal. The US election has changed this reversal into fears of a major and dramatic setback, if we are to listen to the most pessimistic accounts. Nevertheless, there are still good reasons for optimism in the longer term. The data recorded by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) suggests that currently there are three main trends in armed conflicts: a long-term reduction in violence; increasing fragmentation; and geographical concentration.

Less violence in the long term

As the graph shows, the number of fatalities in armed conflicts has fallen sharply in the period since the end of World War II. Several particularly bloody conflicts stand out in the graph. The first peak is the result of civil war in China and of the Korean War; the second is primarily due to the Vietnam War; and the third reflects the Iran-Iraq War and the Soviet Union’s intervention in Afghanistan. On the far right of the graph we see the impact of the civil war in Syria. Despite the setback experienced in recent years, the peaks have gradually become lower, and the long-term trend is still a decline in the number of fatalities. If we had included World War II, this trend would have been even clearer. And the relative fall in violence becomes even clearer if we take account of growth in the global population. In the worst year of World War II, the likelihood for both civilians and military personnel of being killed due to battle-related action was approximately 1:500. In 1972 it was 1:12,000, and in 2014 1:70,000. These figures apply to conflicts where a state comprises at least one of the parties. In the case of non-state conflicts , i.e. conflicts between armed groups where no government is involved directly as a party, the rise in violence since 2011 has also now ceased. The same applies to one-sided violence (genocide and other forms of organized violence against civilians). A total of 118,000 people were killed in armed conflicts in 2015, compared to 130,000 the year before. Current wars have not however reversed the long-term reduction in the risk of being killed in armed conflict.

Fragmentation

The number of ongoing armed conflicts increased sharply during the Cold War, partly due to the emergence of many new and unstable states as the result of decolonization. Following the end of the Cold War, the number of armed conflicts fell by one-third. After the millennium, the number remained relatively constant, before rising again in the last couple of years. One reason for this is the fragmentation of many conflicts. The UCDP has registered three simultaneous armed conflicts in both Syria and Mali, with two simultaneous conflicts being registered in several other countries. In the case of non-state conflicts, this fragmentation is even more marked. The UCDP registered 16 non-state conflicts in Syria in 2015, and 13 in Nigeria. If we look at the number of countries that are experiencing armed conflict within their own borders, there is no increase – in fact we see the opposite.

Geographical concentration

World War II and the Cold War were more-or-less global conflicts. It was difficult for states not to become involved – especially if they happened to be neighbors of the main parties. Armed conflicts occurred in pretty much all parts of the world. Although we avoided direct military confrontation between the superpowers during the Cold War, a number of local conflicts were violently inflamed by superpower support for one side or the other.

Today’s conflicts are different. The most important aspect of this is what is referred to as the East Asian Peace. The region where a number of the bloodiest wars since the end of World War II unfolded has avoided major armed conflicts for over 30 years. In Sub-Saharan African there have also been fewer people killed in armed conflicts than during and immediately after the Cold War. In Latin America, the civil war in Colombia is now the last active conflict, and even that has produced only a modest number of fatalities in recent years.

The conflict picture is now overwhelmingly dominated by the Middle East and bordering regions. In 2015, 86% of the fatalities in inter-state wars and civil wars occurred in an axis from Libya to Afghanistan. Outside this region, only Ukraine, Nigeria, Somalia and Sudan exceeded the threshold we apply to define a conflict as a war (at least 1,000 battle-related deaths in one calendar year). This concentration in the Middle East applies also to non-state conflicts and one-sided violence.

This pattern also has a religious aspect. In general, the countries that are currently experiencing armed conflicts are countries where the majority of the population are Muslim. Terrorist atrocities outside the Middle East are also often perpetrated by Islamists. The vast majority of victims of these various forms of armed conflict are Muslims. But of the four countries with the largest Muslim populations, Pakistan is the only one severely affected by armed conflict. The three countries that lie somewhat distant from the central region of conflict – India, Bangladesh and Indonesia – have long been free of armed conflict.

A reason for optimism?

The picture presented by the media in 2016 may give reason for cautious optimism, but also for the opposite. Tension is rising in Asia, where China is on the offensive and is in dispute with its neighbours about several groups of islands. North Korea has detonated its fifth nuclear weapon, is developing long-range missiles, and is threatening to attack South Korea and Japan. The conflict in Ukraine is very far from resolved. The superpowers are deeply divided about many ongoing conflicts. In the Middle East and in neighbouring countries, scarcely any improvement can be detected.

On the other hand, the conflicts between the United States and Cuba and Iran have been de-escalated. There is a reduction in violence in the countries that have had the most long-lasting internal armed conflicts in the post-war era (Colombia, the Philippines, India and Myanmar). We can detect a shared understanding by the superpowers that they must at least attempt to check the conflict in Syria.

When choosing between a pessimistic and an optimistic interpretation, it may be risky to allow oneself to be guided by daily news reports. All things considered, the long-term decline in the number of fatalities in armed conflicts provides the most reliable basis for cautious optimism.

- Nils Petter Gleditsch is a research professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and is also professor emeritus of political science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU). His book Mot en mer fredelig verden? [Towards a more peaceful world?] will be launched this week by the Norwegian publisher Pax Forlag. The most recently revised update of the conflict data from UCDP was published in Journal of Peace Research in the September issue.

Reference:

Erik Melander, Therése Pettersson & Lotta Themnér (2016) Organized violence, 1989–2015. Journal of Peace Research 53(5): 727–742.

- This article was published in Norwegian in the daily Aftenposten: ‘Lys i enden av tunnelen?‘ 9 November 2016.

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext