In 2017, approximately 90,000 people died as the direct result of armed conflict. This figure is down for the third year in a row, and is now 31 percent lower than in 2014.

Nearly a third of all conflicts – and four of the 10 most serious wars worldwide – now involve a local division of Islamic State (IS).

The largest and most important of the non-state conflicts in 2017 was the conflict between IS and the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Defence Force (SDF). SDF fighters in central Raqqa in 2017. Photo: Mahmoud Bali. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Better but not good

The very latest data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) show that in 2017, there were 10 ongoing conflicts in the world that had each taken at least 1,000 human lives. These 10 wars were taking place in eight countries: Afghanistan, DR Congo, the Philippines, Iraq, Yemen, Nigeria, Somalia and Syria. In addition, there were 39 ongoing smaller armed conflicts, each of which had killed 25–1,000 people.

In Syria alone, there were as many battle-related deaths in 2017 as in all conflicts worldwide just 10 years ago. The most violent year since the start of the new millennium was 2014, when there were over 132,000 battle-related deaths, of which nearly half were in Syria.

IS still a threat

Most of the reduction seen in 2017 in the number of people killed was the result of the war in Syria being somewhat less intense than in previous years. But we cannot take it for granted that this reduction will continue. Although IS is under strong pressure in Syria and Iraq, the organization has put down roots in 15 other countries.

There are active branches of IS in Russia, Egypt, Iran, Lebanon, Turkey, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Pakistan, Chad, Libya, Mali, Yemen, Niger and Nigeria. Many of these branches are local organizations that have applied for recognition as the local representative of IS.

In Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Philippines, the level of violence is so high – with over 1,000 people killed in each country – that we categorize these conflicts as wars. This means that IS is a party to four out of 10 wars. After years of intense warfare, IS has now lost most of the positions it held in Syria and Iraq. But the organization continues to pose a genuine threat.

More non-state conflicts

Forty-nine of the conflicts recorded in 2017 were so-called state-based conflicts, where a state comprises at least one of the warring parties. While the number of state-based conflicts has declined, which has resulted in fewer people being killed in organized political violence in total, we see the opposite trend for so-called non-state conflicts. In 2017, there were 82 active conflicts between non-state actors, which resulted in more than 13,500 deaths. This record high total is attributable to factors such as the outbreak of violent conflicts in DR Congo and the Central African Republic.

The largest and most important of these non-state conflicts in 2017 was the conflict between IS and the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Defence Force (SDF), which resulted in the killing of at least 5,000 people. It is rare for a conflict between non-state actors to result in more than 1,000 killings, but it is also rare for a non-state actor to benefit from significant support from the United States Air Force, as has been the case with the SDF.

In Mexico, a long series of non-state actors, mainly drugs cartels, have been more or less permanently at war with each other over recent years. In 2017, approximately 800 people were killed as the result of these battles. Even so, these killings represent only a small proportion of Mexico’s annual total of 15–20,000 violent killings.

Stable levels of violence against civilians

IS also dominates organized violence against civilians. Of the approximately 7,000 civilian victims of organized violence recorded in 2017, IS was solely responsible for more than one-third of the deaths. Boko Haram, a group with links to IS, was particularly active in attacking civilians in 2017, especially in Nigeria, Cameroon and Niger. The Rohingya minority in Myanmar is one of the world’s most vulnerable ethnic groups, and 388 Rohingyas died as a result of one-sided violence in Myanmar in 2017. An San Suu Kyi’s government has been strongly criticized internationally for its failure to stop the bloodshed.

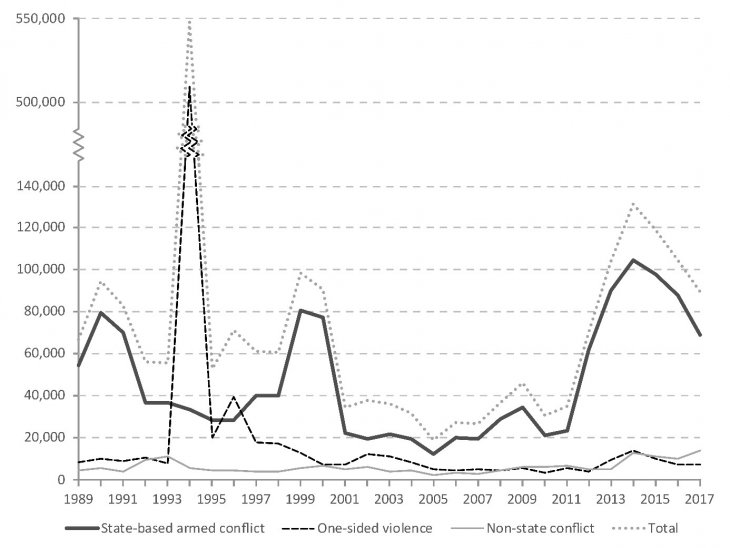

Formally organized non-state groups were behind the majority of organized violence against civilians in 2017. This has also been the usual situation in recent years. Even so, states are responsible for killing most people over the longer term. The largest genocides in modern history completely dominate overviews of the numbers of people killed. 65 percent of all killings of civilians since the end of the Cold War took place in Rwanda in 1994, as shown in the Figure 1. In fact, over 20 percent of all victims of all types of political violence in this period were in Rwanda. Syria accounts for approximately 13 percent of this total, Afghanistan approximately 7 percent, and DR Congo, Iraq and Ethiopia/Eritrea each account for approximately 4 percent.

Figure 1. Total number of fatalities in organized violence by type, 1989–2017 . Source: Pettersson & Eck (2018), Journal of Peace Research

Only one interstate conflict

All of the largest anthropogenic disasters in modern history are the result of either genocide or interstate conflict. The war between Ethiopia and Eritrea in 1998–2000 was the most recent major conflict between two countries and resulted in the killing of over 100,000 people. This conflict has threatened to reignite several times, most recently in 2016. Fortunately, this has not happened.

In 2017 there was just one conflict between two states that took more than 25 lives: the conflict over Kashmir between India and Pakistan. Even though this conflict has the potential to become a major war, the number of people killed has remained at a low, stable level since 2003.

Approaching the UN Sustainable Development Goal?

The main aim of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal number 16 is to reduce the number of people killed in armed conflicts worldwide. Compared with the situation 10 years ago, it may seem as though the international community has lost some of its most important means for dealing with war and conflict. Ten years ago, the UN Security Council was an effective body that was willing to intervene where conflicts were on the brink of chaos. That will no longer exists.

In recent years we have seen a major growth in the number of conflicts where external parties are involved. This is a worrying development that increases both the intensity and duration of conflicts. How IS develops in the future is accordingly extremely important. Will the setbacks experienced by IS in Syria and Iraq leave the organization significantly weakened, or will it be an actor we must take into account for many years to come? Only time can tell.

- This text was published in Norwegian in Dagsavisen on 25 June 2018: ‘Færre mister livet i konflikt‘

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext