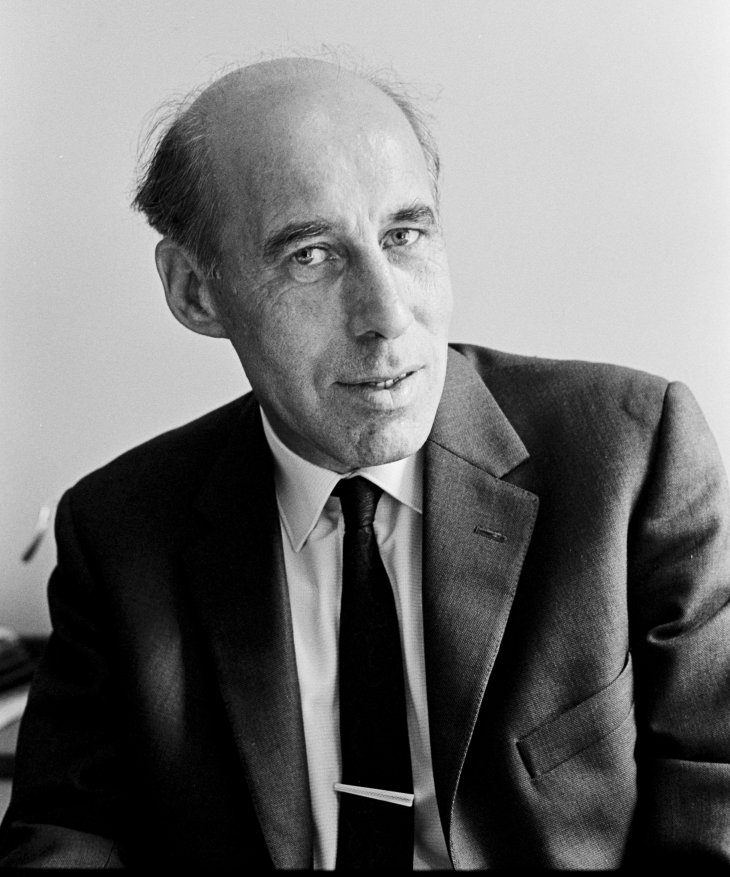

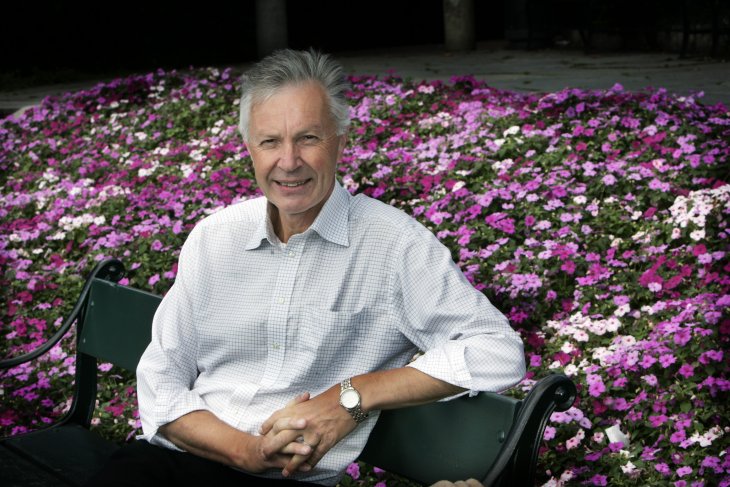

Sverre Lodgaard (right) with John Sanness (left; 1913–84), director of the Norwegian Institute for International Affairs 1959–83 and leader of the Nobel Committee 1979–81.

Sverre Lodgaard, interviewed by Hilde Henriksen Waage

What kind of journey was it, from life as a young researcher at PRIO in the 1960s, to directorial roles at PRIO and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s? How do Sverre Lodgaard’s life and work connect with his research career, his directorial roles, and social trends? And how does his journey relate to the evolution of PRIO over a period of 60 years?

The journey runs from a small village in Trøndelag County, where Lodgaard spent his childhood and early teenage years, to Oslo. When, how, and why did Lodgaard arrive at PRIO, and why did he end up in jail for refusing to do military service? In the 1970s, PRIO became notorious for its political radicalization. Lodgaard’s research areas – East-West relations; the anti-nuclear movement; non-proliferation; disarmament; and heavy water – were a perfect fit with this radicalization.

But 1987 represented a watershed. That year, after having spent several years at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Lodgaard returned to PRIO as the organization’s director and embarked on a massive clean-up operation. PRIO was transformed from an institute of hippies and left-wing radicals into a reputable research institute, welcomed in from the cold by the Norwegian Ministries of Defence and Foreign Affairs, political authorities, and the Research Council of Norway. A new epoch had begun.

Hilde Henriksen Waage: Who was the young Sverre who started out on this journey?

Sverre Lodgaard: I was born into a working-class family in 1945 and was the younger of two brothers. Like the other inhabitants of Singsås, a village halfway between Røros and Trondheim in Trøndelag County, we had what we needed, but nothing more. It was a good start: a small, very secure and stable community to grow up in.

The village had a few hundred inhabitants. I read with interest the little I could find about the wider world. In 1959 I moved to Trondheim and started at the Cathedral School, which was then a lower secondary school followed by gymnasium (college). However, my favourite subjects weren’t social sciences, but maths and physics. When I realized that the laws of nature could be expressed mathematically, I was walking on clouds. I thought it was utterly fantastic.

Given that maths and physics were your favourite subjects, and that you were living in Trondheim – Norway’s technological citadel – why on earth didn’t you study science? Why didn’t you become a civil engineer?

I came across a prospectus for the University of Oslo and read about something called political science. It sounded interesting and I had an early interest in politics, so I ended up there. But only for a year, I thought, then back to science.

You say that you came from a Labour Party or working-class family. In other words, not from an academic background. Did your parents run a farm? Did they have other jobs alongside?

My father was a carpenter and my mother a housewife. In other words, roles along traditional gender lines. My mother kept the house in good order, and my father worked hard and kept long hours. They wanted me and my brother to have an education, which was fairly typical of the times. They understood that this was the future.

But there must have been something in your background, your genes, that meant you had the ability and aptitude to study science, then later on political science.

My mother thought it was a pity not to have any higher education. She talked about that several times. My grandfather was a farmer and he ran the farm very well. He had five children. Two boys. The elder would take over the farm, and the younger had to get an education. He became an electrician. The girls didn’t need any education because they would get married and be provided for. He was old-fashioned, my grandfather. My father went to folkehøgskole (Folk High School) [school with no exams], nothing beyond that, but he was good with numbers.

So, you moved to Trondheim?

I lived there for five years altogether: two years of lower secondary school and three of gymnasium. I lived in a bedsit during the week. It was only an hour-and-a-half by train from home, and I went home every weekend. So it wasn’t that big a deal. Before that I went to the local school in Singsås every other day – Monday, Wednesday and Friday, or Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. That way we got pretty good at cross-country skiing. Having finished the gymnasium, my brother encouraged me to do something else for a while – that is, something other than maths and physics. That “something” became political science.

Singsås. Photo: NTNU Museum via Flickr / CC BY

Political Science

Indeed. So, hadn’t you thought at all about this Oslo plan before reading the university prospectus?

No, I was easily influenced at that stage. In the beginning, I thought this new field of political science was a peculiar subject. I didn’t really get the hang of it. To a seasoned scientist, it seemed fuzzy and hard to pin down, but after half a year it began to dawn on me what it was about.

But you must have liked political science, because you carried on with it?

I liked it more and more. Especially as student politics gradually took hold. That peaked with the Oslo Student Association. I was on the Board, vice chair, in the spring semester of 1967. There were Wednesday and Saturday meetings. After the Saturday meetings we were often on the front pages of Oslo newspapers the following Monday, with reports on debates of public interest.

And we had unlimited amounts of money! At that time, more beer was sold at Dovrehallen [a famous beer-hall in Oslo] than at any other place in Norway. We had an annual net profit of one million kroner, a large amount of money at the time. When inviting speakers and planning the artistic interlude between the lecture and the debate, we could therefore choose pretty freely.

So did these Saturday meetings have a set programme, with a lecture, an external lecture, an artistic interlude, and then a debate? What was it that caused you to be all over the newspapers on Monday mornings?

The Student Association was a time-honoured, important platform. It had been for a long time and it stayed that way right up until the Marxist-Leninists of the Workers’ Communist Party (AKP-ml) came along, took over and ruined it.

But during the same time, you continued your studies, held 13 elected roles of various kinds in student politics, and sat on the Board of the Student Association. And you also had to decide on a research topic – what to focus on and write about for your magister degree. With your interest in maths and physics, you could have opted for a quantitative approach to political science, but you didn’t do that?

Johan Galtung and PRIO

While I was sitting in no. 11 Uranienborgveien in Oslo [U11, the administrative office of the Student Association], I got a phone call. I can’t remember from who, but I was asked if I would be interested in becoming an assistant to Johan Galtung. It was a paid job. NOK 800 a month. The way I saw it, I would have been a complete idiot to say no to that. Money was pretty tight at the time.

Galtung had a project for the Council of Europe, and it was in that connection that he needed an assistant. As for the topic of my dissertation, I said to Johan that I would prefer a topic where I could apply quantitative methods. That was not to be. The dissertation was about interaction patterns across the East-West divide in Cold War Europe and did not require much of that kind.

But did that mean that at the same time as you were writing your magister degree thesis, you arrived at PRIO as an assistant on a project for Johan Galtung, funded by the Council of Europe? And did this contribute to determining your choice of topic for your thesis?

The thesis was inspired by the Council of Europe project, and so I decided to study international relations, that particular branch of political science. In the years that followed, my own research was about European politics – across the East-West divide.

We have now got to the topic of PRIO. Because here we have two parallel tracks: completion of your studies at the University of Oslo and your arrival at PRIO in 1967. I’d really like to hear more about this Johan Galtung. Today, many people are still well aware who he is. I remember him from NRK [the Norwegian national broadcaster] when I was young. He appeared on television drawing rectangles and diagrams with a marker pen. That fascinated me enormously. That was many years before I realized that I would end up at PRIO. But what was Johan Galtung like when you arrived? What was it like to have him as a mentor and perhaps as your guiding star? Were there advantages? Disadvantages?

It could be a roller-coaster ride – with strong encouragement and strong criticism. No doubt that was part of his personality. I think most students experienced both sides. With hindsight, it is easy to see that he was an excellent supervisor. For example, I was asked to write a chapter for Cooperation in Europe, the book from the Council of Europe project, and the first draft I sent to him – he was somewhere in India, with Arne Næss [legendary professor of philosophy] – certainly wasn’t much to speak of. It was poor. When I got his comments, he had picked some elements that perhaps weren’t all that bad and indicated how I could develop them. In effect, I was encouraged to write a whole new text, which I did, and which actually became a chapter in the book.

Generally, Johan was first and foremost an enormous source of inspiration. I believe some of his best publications date back to the years around 1970, combining theoretical sophistication with empirical research and rigorous methodology. The results were outstanding. His article on imperialism, A Structural Theory of Imperialism, from the early 1970s, may still be his most cited work.

Was he around much at PRIO, or had he already started globe-trotting?

He has described those years, the second half of the 1960s, as PRIO’s golden age. I can well understand why he saw it that way. Then, the foundations were being laid for a series of new recruitments. It was an exciting time. Galtung communicated well and was inspiring also for people involved in practical politics. We hadn’t yet seen the most radical version of him. This manifested itself in the Peace Academy, for example, which I took over from him and headed for a while.

What was the Peace Academy?

Researchers, civil servants, military officers, journalists and MPs met at PRIO at 10am on Saturday mornings, and we stayed until 2-3pm debating issues of current interest. Originally, a lot was inspired by Johan, but others also made opening interventions. At that time, Johan, the academic man, may have harboured another, related ambition. I believe he would have liked to become head of some international organization. He actually put himself forward for the role of rector at the United Nations University in Tokyo. As you know, that didn’t materialize. Instead, he increasingly distanced himself from establishment politics and particularly from the Norwegian political establishment.

Would you say that both PRIO and Johan Galtung himself were reputable at the end of the 1960s with contacts in the political community, hosting seminar series, debates and serious research? And that political radicalization hadn’t yet really taken hold, either in Galtung or among PRIO’s researchers?

The very nature of peace research meant that since the East-West divide was the major line of conflict in international politics, the focus of our research had to be on reducing tensions, building bridges and seeking solutions. Accordingly, PRIO evolved in a different way from other Norwegian research institutes.

Most of what NUPI [the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs] stood for in the area of security policy had an obvious basis in Western interests, and in Norwegian interests as part of the Western world. PRIO was different, but so far, we liaised very well with proponents of mainstream Norwegian foreign policy.

At the start of the 1970s, there were major changes. A number of younger researchers, of your age plus or minus a few years, arrived at PRIO. I don’t know in what order, but didn’t Nils Petter Gleditsch, Helge Hveem, Per Olav Reinton, Tord Høivik and Ottar Hellevik all arrive at PRIO in the late 1960s or early 1970s?

The ones you mention are all three, four, or five years older than me. They were already there when I arrived. I was the Benjamin of the family for a short period. And then Kjell Skjelsbæk arrived a bit later, soon after me. It was a good community to join. Politically, it was in opposition to official Norwegian foreign policy, and that was okay with me. There was a striking level of self-confidence in the group. At times, we made bold arguments that probably went beyond what was reasonable, with all the fervour of youth.

Labour Party Politics

Would you say that the battle over the EC, in other words, over Europe, was the first topic that made political involvement and radicalization take off? Or were there other topics?

That was at any rate the first political issue that engaged us all very strongly, except for the Vietnam war. Here, too, we argued with great self-confidence, and I think we were pretty good at it. I remember hearing via back channels from people we had invited to debates, and who were on the other side, that they had thought it over more than once before accepting our invitation, being uneasy about what they would encounter. And that they were relieved when debates ended in fair fashion for all involved. We were a young, successful, slightly zealous group, who came from an interesting and well-reputed institute.

Weren’t any of you in favour of the EC at that time?

PRIO was against membership of the EC, and NUPI was for it. Some collaborators at NUPI were against, and they left the institute for a period of time. They – Harald Munthe Kaas [who became a well-known media commentator and author] and Arne Treholt [who would later go into politics, become a state secretary, and be arrested and convicted of spying for the Soviet Union and Iraq] – set themselves up in an apartment at Skøyen. There was no room for them at the inn. The fronts were hard at that time.

And they were to become even harder. This was primarily a political matter. This wasn’t the theme for your research, was it?

Actually, for me it was. I learnt much from the works of Martin Sæter, supervisor for my thesis. My television debut, by the way, was also on the emerging European integration and how Norway ought to relate to it. It was a debate with Einar Førde [Labour Party MP and minister, among other things] siding with me, and Johan Jørgen Holst [later head of NUPI and Labour Party defence and foreign minister] on the other side. Two people on each side; you were either for or against.

Were the political roots of most researchers at PRIO, yourself included, basically in the Labour Party? They weren’t on the far Left. You didn’t flirt with the Workers’ Communist Party or similar groups?

Few flirted with the Workers’ Communist Party, but there were a lot of people who weren’t in Labour. And the founder himself certainly wasn’t a Labour Party member. He did not want to have anything to do with the Norwegian America Party, as he called it.

So, was he a member of any political party?

No, I don’t think so. He kept his distance from all parties, although he had close contact with Knut Frydenlund [a Labour Party MP and later foreign minister] and Finn Moe [chairman of the parliamentary foreign affairs committee]. Finn Moe had radical leanings, and he took an interest in what was going on at PRIO. Earlier, he had also been among the initiators of NUPI.

Given your background, your childhood and teenage years, is it correct to say that you personally had links to the Labour Party?

I sympathized with it before I came to Oslo. Then I became a member, and in 1969 I was recruited to its International Committee.

What was that?

The party had an International Committee that functioned best when the party was in opposition, and in 1969 the party was out of office. The chairman was Reiulf Steen [MP, minister and leader of the Labour Party 1975–81]; later Knut Frydenlund took over, and Guttorm Hansen [Labour party MP and President of the Storting] was a driving force at that time. Much of what I had worked on in connection with Cooperation in Europe – building bridges over the East-West divide – naturally translated into a keen interest in West Germany’s Ostpolitik. On the International Committee, it was primarily Guttorm Hansen who represented that thinking and reported on the Brandt-Scheel coalition’s Ostpolitik. [Willy Brandt was the leader of the German Social Democrats and Scheel of the German Liberal Party]. Guttorm Hansen visited Germany and made incisive reports on developments there.

Journalist and politician Guttorm Hansen. Photo: Frits Solvang / CC BY / Oslo Digital Museum

But am I correct that, over the longer term, your relationship with the Labour Party has fluctuated?

Things got so stormy during the EC debate that there were consequences. I decided to leave. My wife [Ingrid Eide] said I made no bones about it, so when Knut Frydenlund phoned and wanted to talk about the agenda of the next meeting, I told him in no uncertain terms. I left the party in the spring of 1973 and joined the Socialist Electoral Coalition [Sosialistisk Valgforbund, a precursor for the Socialist Left Party], but I didn’t join the Socialist Left Party when it was founded. Right until the start of this century, I wasn’t affiliated with any party.

So where have you ended up now?

I went back to where I began. When I returned from the UN in 1997, I once again became member of the International Committee. The Labour leader was now Thorbjørn Jagland. After a while he wanted me to chair the committee, and I accepted. I made it clear to Thorbjørn that I wasn’t a Labour member, but he didn’t think formal membership was important.

I had a free hand to issue invitations to the meetings. It depended on topic and competence. Membership of other parties wasn’t a barrier as long as the person in question was not known to have a leading role. There was a lot of interest in attending, and I found it all productive and rewarding. We had some very good discussions.

I took on this role for social as well as political reasons. When I returned from the UN, I wanted to re-establish contacts and dip my finger into what was going on in Norwegian politics. Not on a weekly basis, not even every month, but perhaps every other month in connection with some issue or other of topical interest. Then, in the beginning of this century I got a phone call from a Labour MP in connection with my deputy membership of the Nobel Committee, appointed by the Labour Party. Winding up, he suggested that I pay the membership fee. Being involved in a bit of party work at that stage, I thought I might just as well do so. That’s how I got back to the roots.

There are some recurring themes here. Your political engagement is really a factor throughout your whole journey. You changed party affiliation slightly, but not your actual political standpoint. Is it fair to say that’s pretty firmly within the Labour Party?

Yes, on the left wing of the party. But there has been no continuity in my political engagement. I could engage, on and off, on issues that I thought were interesting and important, but then, after a while, I did not have the stamina to follow up. New issues, new interest, and then a new lull. Guttorm Hansen invited me to the Storting [parliament] and put me in the Press Gallery so I could see how parliamentary life played out in practice. Perhaps he had a longer-term motive for doing so. But when I left the party in 1973, it was clear to me that I was not made for politics. I realized that I should concentrate on research.

Indeed. No doubt many people think that researchers – including me – at PRIO and at other places that conduct research on international questions really want to be politicians. But what we really enjoy is getting on with our research. We have a desire to learn more, think, and analyze. That’s what we really like doing.

Yes, no doubt we think – both you and I and many others in our profession – that there is more excitement in research-related problems than in humdrum day-to-day politics.

A Conscientious Objector

As an introduction to the major topic of political radicalization in the 1970s, which would result in PRIO being branded a disreputable institute populated by hippies and radicals, I’d like to talk a little about you and military service. Because in the 1960s, military service was compulsory in Norway, and all Norwegian men were conscripted. And that would certainly also apply to you.

Initially I applied for, and got, a deferment. Meanwhile, I had begun writing about nuclear weapons and nuclear policy. I had my views about the Norwegian Armed Forces and their integration into NATO, in which nuclear weapons were an important element.

At the same time, we had our own self-imposed restrictions – no stationing of nuclear weapons in time of peace, no foreign military bases, no flying of allied aircraft over Norwegian territory east of 24 degrees. As for nuclear weapons, this meant that Norwegian military personnel didn’t get any training in the use of such arms. Even so, nuclear weapons were part of Norway’s defence strategy. The implication was that allied forces, not Norwegian troops, might use these weapons on or from Norwegian territory in case of war. The reasons for my conscientious objection evolved over time and I ended up with the slogan Armed and Defenceless.

At its peak, NATO had 7,000 nuclear weapons in Europe alone. […] I drew a line in front of myself and said: ‘not this’, and I’ve never regretted taking a principled stand. […] It was classified as politically motivated conscientious objection, and the court ruled that I had to go to prison.

What did that mean?

At its peak, NATO had 7,000 nuclear weapons in Europe alone. When there were large-scale NATO exercises and these weapons were used in war games, the supreme commanders reported that Europe had been destroyed. Everything that was supposed to be defended would be destroyed if such weapons were used. I drew a line in front of myself and said: ‘not this’, and I’ve never regretted taking a principled stand.

However, there was no basis in Norwegian legislation for allowing someone to do alternative civilian service for such a reason. It was classified as politically motivated conscientious objection, and the court ruled that I had to go to prison. Stjørdal and Verdal District Court found that the minimum sentence required by law, three months, would be enough. The prosecutor appealed to the Supreme Court – four months had been the usual – but the Court upheld the sentence.

And so you had to serve a prison sentence?

I served it in the Bayern section of Oslo County Jail. I was offered another place where conditions were more benign, but I wanted to see how the ordinary prison system worked. For me, this wasn’t punishment of the kind that hit many others. Other inmates might lose their jobs, their families might fall apart, and so on. None of this applied in my case. At first, my impressions of prison life fluctuated, but after three months my understanding of life behind bars had stabilized.

Oslo County Jail. Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

So, you had to serve your sentence in Oslo County Jail in an ordinary cell? It’s just unbelievable to be sitting here and hearing that. Who were your fellow prisoners? All different types?

All sorts of law-breakers. There was no segregation according to type of crime. And this was the first time I saw people using narcotics. The drugs were given to a prisoner on remand. The stuff was injected into oranges and his lawyer was the courier. After three weeks behind locked doors, I got a job as assistant orderly – I’d realized that was the perfect job, because then my door would be unlocked from early in the morning until five in the afternoon and I could read and write a bit in-between work in the corridors.

I was offered another place where conditions were more benign, but I wanted to see how the ordinary prison system worked.

I commented on a book manuscript by Gunnar Garbo [a Liberal Party politician and peace activist] and finished an article for the Journal of Peace Research. I handed out food, brought clothes to and from the laundry, and cleaned cells. When I delivered the meals, the prisoner would often stumble slowly from his bunk, in a daze. I’d shout that he had to bloody well get up and take his food! I didn’t realize what was going on. Drugs. As early as 1974.

Yes, but presumably this made an impression?

It did, because it was a new world for me – and I stayed in touch with a couple of inmates afterwards. One of them had been imprisoned during the war, but never in peacetime – until now. He and two close relatives had explored 10 different ways of earning money, including stealing and selling Volvos. He was a trained engineer and used a drill bit that was so fine that when he picked the steering-wheel lock, no one could see the hole with the naked eye. After I was released, it wasn’t long before he got out too. He helped me install the electrical equipment in my new apartment and turned up in a modern Volvo! The story had its colourful aspects! I heard from him some years ago, from Spain.

Life in prison could be a bit dismal, especially in the beginning, so when I was set free for a few hours each week to give my introductory lectures on international affairs at Blindern [the University of Oslo] I thought it would be a relief. It turned out differently. Time passes rather quickly when you get into the rhythm of prison life, but the hours at Blindern took me out of that rhythm. So, in a sense I was happy when the lecture series ended. I got out in December 1974.

PRIO’s Egalitarianism

The third group of questions concerns political radicalization in the 1970s. PRIO became an institute with a fairly bad reputation. It’s worth noting that when I arrived at PRIO in 1984 as a young postgraduate, you weren’t there, but I found an institute populated by hippies and radicals – a situation I could scarcely have imagined given my conservative upbringing in the Salvation Army and other evangelical communities.

So, perhaps we should begin with how PRIO was structured. And here, I think, for the sake of readers in 2019, we need to proceed step by step, in considerable detail. In 1971, a new structure was introduced at PRIO – it was still in place when I arrived in 1984: the staff meeting was the highest decision-making body. Everyone had an equal vote, whether you were a secretary or a researcher. The structure was completely flat [egalitarian]. There was no hierarchy of any kind. There was a ‘leader’, who was elected on a rotating basis. And there was a salary system that eventually resulted in a secretary becoming the top earner. So, I’m wondering: what was the point of this new structure? Why was it introduced?

The background was a strong collective feeling, reinforced when Johan took off for other parts of the world. His departure meant that we had to find a way to govern ourselves. In the beginning, I thought it was an appropriate structure, not particularly problematic. The people who were there – you listed them a while ago – functioned well as a collective. And it was the spirit of the age – at least among those of us who were there at the time. Ideas about egalitarianism, staff meetings, and collective structures were considered fair and reasonable. So we tried it out. But once the arrangements were put into practice, objections emerged, little by little, and over time they became pretty strong.

When this system was introduced, Johan Galtung had left PRIO, so the researchers there at that time were Asbjørn Eide, Helge Hveem, Marek Thee, Tord Høivik, Nils Petter Gleditsch and you. In the politically radical atmosphere of the 1970s, you had a strong belief in the collective, in solidarity, which you thought would function successfully. So was there agreement initially about having an elected leader, which would be a rotating role; about the staff meeting having the highest decision-making authority; and about the flat structure and the salary system?

No one emerged as the natural leader when Johan left, and there were ideological undercurrents working in the direction of a flat structure. The group you mentioned functioned well together, so the staff meetings naturally became the highest decision-making authority. The salary system came a bit later. That system put the flat structure to more of a test, but initially we all supported that, too.

What was the basis for the salary system?

Everyone was supposed to have equal pay. Ideally, an equal hourly wage regardless of position. Researchers and administrative personnel were to be paid on an equal basis. It was pursued so energetically and zealously, particularly by Nils Petter and Tord, that it had a provocative effect on some of us who had supported it at the beginning but saw more disadvantages as time went on. Disagreements about the salary system caused tensions within the group. So when the Institute got into a hostile encounter with Norwegian authorities and public opinion at the end of the 1970s, PRIO was an institute at war with itself.

Revealing Military Secrets

At the same time as this was going on, a drama was playing out in several acts under the title The Battle Against Secrecy. This title covered a number of related issues. What was your view of this unfolding drama, which ended with PRIO being branded a spy institute, and with Nils Petter Gleditsch up in court and being found guilty?

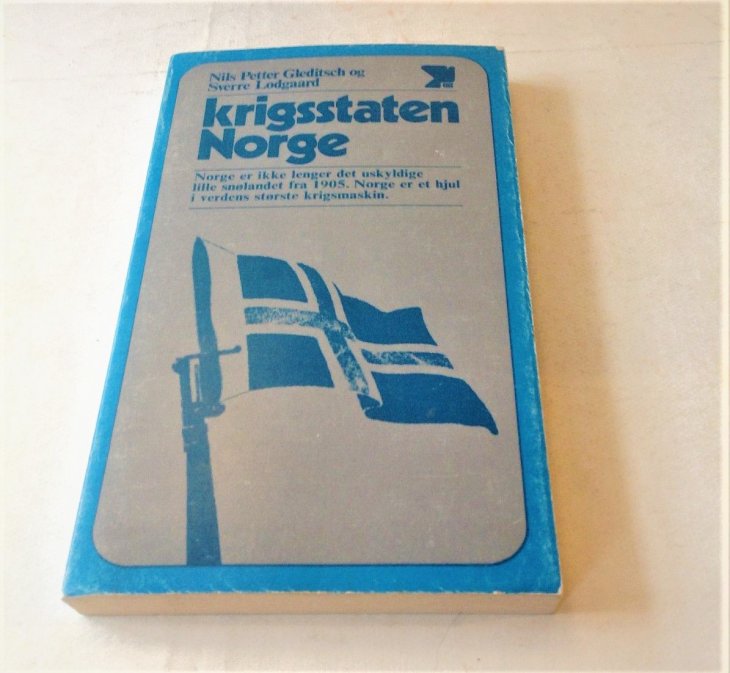

On my part, this goes back to a book that Nils Petter and I published around 1970 called Krigsstaten Norge [Norway – the Warfare State]. The title was borrowed from the title of an American book, The Warfare State by Fred Cook. Our intention was to shed light on how much, and in what ways, Norwegian politics and society might be considered militarized, and the consequences of this. In the Norwegian context, the title was hype. It did not resonate. So that was a blunder. But there was nothing fundamentally wrong with the project. Already at this stage we were trying to bring out into the open things that had been relegated to the shadows. The battle for transparency, against secrecy, had already started.

By way of extension, Nils Petter and I had a harder look at Norway’s self-imposed weapons restrictions. What were the actual contents of these restrictions? How did they work in practice? Under bilateral agreements between Norway and the United States, we put our territory at the Americans’ disposal. The United States financed the installations, and Norwegian personnel were assigned to run them in order not to breach Norway’s base policy, which prevented foreign military personnel stationed on Norwegian soil in peacetime. Times of war and crisis were a different matter. We tried to bring out into the open matters that the authorities weren’t so eager to talk about. They might be our own ‘secrets’, or it might be American ‘secrets’, but to a large extent we were targeting Norwegian secrecy, because classification of information was more comprehensive in Norway than in the United States. Norway was more closely aligned to the British tradition, which had relatively strict classification rules.

So far, nothing had caused any fuss. For instance, Nils Petter and I wrote an article for the Nordic journal Cooperation and Conflict about the self-imposed restrictions, which received favourable comments from many quarters. Then, a military officer, Anders Hellebust, arrived at PRIO with a magister degree thesis in the making. It was fed into the PRIO context, and Nils Petter knew how to shape it with a view to public attention. I was also a part of that. At that point in time, a mentality had developed along the lines that since we thought it important to bring things into the open, we should also ensure that we got decent media coverage.

Krigsstaten Norge [Norway – the Warfare State], written by Nils Petter Gelditsch and Sverre Lodgaard in 1970.

We weren’t in the media so much in the late 1960s and early 1970s. But when these projects began to take shape, we thought that if we were to be successful, we would also have to summarize our messages in straightforward, easily understandable words and feed them to the media. To exaggerate a little: getting into the media became a criterion of success. We thought we had something interesting and important to present, and media coverage became a criterion of success.

So there was no research-related disagreement between you and Nils Petter? In fact, quite the opposite?

That’s right. We had coinciding research interests, and we co-authored some publications.

But all these cases – the ‘lists case’, the (Finn) Sjue case, and several others – meant that PRIO increasingly encountered massive prejudice from many quarters, and as time went on, universally, not least from the establishment media. The overall effect of these cases, political involvements, statements in the media, research interests and focus, meant that suddenly PRIO had drifted into a kind of shoal of unfortunate situations.

That’s a bit exaggerated. But the report on the Omega and Loran-C stations (which had been set up on the Norwegian coast to help US submarines navigate) was controversial, and then came the report that set out to map US-Norwegian intelligence cooperation. There wasn’t anything earth-shaking until then, but then it came, suddenly and brutally. Above all else, that was the parting of the ways.

So here you’re referring to the court case and the charging of Nils Petter Gleditsch and Owen Wilkes in July 1979, the court case in May 1981, the verdict in June 1981, and the hearing before the Supreme Court in February-March 1982. It was this case that became the high – or the low point – so far. But from the end of the 1970s and up until then, Nils Petter had made an enormous contribution, both in terms of research and also political engagement.

And he ran this project with customary enthusiasm and systematicity in order to uncover as much as possible about what kind of operations were taking place, especially under the bilateral agreements between Norway and the United States. It wasn’t necessarily the case that Nils Petter thought it was unreasonable for Norway to put its territory at the disposal of American operations. We had a security guarantee from the United States, and this was a significant part of the bargain. But he thought the secrecy was detrimental.

In the United States, if investigative journalists use open sources to establish that something spicy is going on that hasn’t previously been brought into the public domain, that’s the politicians’ problem. In Norway, things were viewed differently. And perhaps it is fair to say that the situation wasn’t quite as clear-cut as if the material had been obtained exclusively from open sources. For example, if you get close to a military intelligence station and see a sign prohibiting entry, but then find another way without a sign and go in that way, then you’re in a grey area. On the margins, sole use of open sources may not have been clear-cut.

And then came the report that set out to map US-Norwegian intelligence cooperation. There wasn’t anything earth-shaking until then, but then it came, suddenly and brutally. Above all else, that was the parting of the ways.

When the report was in draft form, Nils Petter invited me to read the first 30 pages. That was only natural, given that we’d collaborated on similar issues for many years. I then went to his office and said there’s a 50 percent chance you’ll be prosecuted. But he wasn’t having it. He found my assessment completely unreasonable. His understanding of the political and social consequences of his work had significant flaws.

Why wasn’t it natural for you to collaborate with Nils Petter on this?

It was something he was doing on his own, together with Owen Wilkes. Without remembering the specific details, it wasn’t that he invited me to collaborate and I said no.

Because wouldn’t it have been obvious for him to ask you?

In a sense it would. Probably, there were other intervening factors here. We were busy doing different things. I had begun writing for SIPRI’s Yearbook: from 1976, I wrote the nuclear non-proliferation chapters. But it certainly also had to do with the nature of the work. It was sufficiently sensitive for Nils Petter and Owen Wilkes to find it best to keep things to themselves. PRIO wasn’t kept informed about what was going on. However, to the extent that anyone else at PRIO had any insight into what was going on, it would have been me.

With hindsight, doesn’t it seem a bit strange that you and Nils Petter, given that your research interests were really very closely aligned and that you had written and edited several books together – both this one about Krigsstaten Norge [Norway – the Warfare State] and the one about Norge i atomstrategien [Norway in the Nuclear Strategy] – didn’t continue your collaboration on this in 1978–79, and that it became a Nils Petter/Owen Wilkes project? One that you didn’t participate in, or didn’t want to participate in, or weren’t informed about?

I didn’t have any wish to join the project, and I don’t think Nils Petter had any wish for that either. But we did have a research relationship that was close enough for me to be aware that something like this was going on. And I was interested in some related questions that didn’t have to do with military intelligence, e.g., to what extent Norwegian researchers had accepted money from the American military to conduct research for them and to what ends. But I never wrote about it because Nils Petter and Owen were leading that work too.

In the aftermath of the publication of the report by Nils Petter and Owen, there was internal uproar at PRIO. In an earlier interview, you said that the report was like a bomb. And in light of the highly collective, close-knit nature of PRIO, isn’t it really somewhat strange that a report and a research project would come suddenly, like a bomb? Tord Høivik was leader at that time, and he experienced it as very unpleasant. What are your own recollections of this?

Of course, it was a paradox that a project that aimed to uncover secrets had itself been kept secret from the rest of PRIO’s staff. The fact that such a project had even been worked on hit the staff like a bomb. I was in a special position, because I knew that something like this was afoot, as I mentioned when I referred to my comment to Nils Petter after I’d read the first 30 pages. And to repeat, Nils Petter and Owen can’t have understood the political consequences of what they were doing. Their enthusiasm and determination to uncover things that had been out of sight got out of hand.

A week after the report was published, PRIO issued an official statement, which said that the publication of the report by Nils Petter Gleditsch and Owen Wilkes would have been stopped if it had been subject to a ‘broad administrative process’. The statement was written by the permanent staff members at PRIO, which included you. And it emphasized that PRIO was not taking a position on the content of the report, but that the work on the report had been kept virtually secret from the rest of the staff.

Yes, it was – with me as a minor exception.

But isn’t it really quite extraordinary that all the permanent researchers at PRIO went public with a statement criticizing Nils Petter Gleditsch and Owen Wilkes?

Well, it hadn’t happened before. And I’m pretty sure it hasn’t happened since.

Institute at War with Itself

So, by then, was PRIO no longer a pleasant place to work?

The sum of several events meant that it had become very unpleasant. The report on military intelligence brought things to a head – it was the last straw. But at the same time, the salary system and the flat structure was also a major source of tension and misgivings. We’d all been in favour at the beginning, but many of us became more and more lukewarm as we saw that the system wasn’t working. In that respect, much of the responsibility rests with Tord and Nils Petter, because they implemented the system with such an alacrity that when PRIO came into the spotlight because of the said report, it was an institute in conflict with itself. At that point, there was very little that was positive about being at PRIO.

So events happened in parallel here: the onslaught of massive media attention in connection with the publication of this report, and at the same time, a feeling among other PRIO researchers that they hadn’t been kept informed, or at least not well enough?

The staff weren’t kept informed.

But you had seen the first 30 pages?

Yes.

And at the same time, the third factor was an ongoing and growing conflict about the flat structure and the salary system.

That’s correct.

Six Years at SIPRI

That led to you leaving PRIO in 1980. Why did you leave? Where did you go, and was this linked directly with the internal conflicts?

It was a case of pull as well as push. I was already writing for SIPRI – the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. SIPRI was very well funded and had an excellent infrastructure. I worked there for six years. Very rewarding years. At the time, it was an optimal home for me. PRIO was the opposite. An unpleasant workplace. I was unhappy and wanted to get away. In that sense, things were pretty simple for me. Though it was inconvenient as far as my family was concerned, even Ingrid [Eide], my wife, thought that it was the best solution. The situation at PRIO had become pretty unbearable.

And Ingrid, who was one of PRIO’s founders, was no longer at PRIO. So where was she?

She had a position at the University of Oslo, at the Department of Sociology, and spent some time in Parliament as an MP for the Labour Party. It had caused a bit of a stir – also internationally – that Ingrid and Johan [Galtung] had separated at the end of the 1960s and that I had married Ingrid. But it happened without causing Johan and me to fall out. We could have our disagreements on other matters, but the relationship was not damaged because of family affairs.

The reason for that had much to do with the coincidence and timing of what happened on his side and what happened on mine. He married a Japanese woman, Fumiko Nishimura. In the spring of 1971, just as I had finished my magister degree, we travelled together to an international conference in Romania and had a pleasant time. And Johan was on the committee for my dissertation.

So to start at the beginning, what happened was as follows: two of PRIO’s founders – Ingrid Eide and Johan Galtung – were a married couple. Was it in 1969 that Ingrid and Johan Galtung got divorced?

Yes.

And then, my goodness, Sverre Lodgaard marries Ingrid Eide, the ex-wife of Johan Galtung.

Later that year.

Indeed. There wasn’t any hanging around here. You went straight into new relationships, because at the same time as Johan Galtung found his new Japanese wife, while you continued to have an excellent relationship with Johan Galtung, both professionally and personally, he sat on your magister degree committee, and everything was just fine. Have I got that right?

We were both a bit proud of it. But without the fortunate circumstances – the simultaneity of things – it could hardly have ended that well. And apropos your question, I fully understand that it is of some interest, in the context of PRIO’s history, to know what happened.

Yes, I think it’s really good that you’ve said this. Because I’ve been wondering whether I would dare step into this territory. But of course, it is true that this isn’t a completely personal matter, because it did involve the real core of PRIO’s founders and a permanent staff member.

Well, yes and no – I can’t see that it had major consequences for anyone.

No – but it could have had. If things hadn’t gone well, there could have been consequences. So does this mean that in 1980, you and Ingrid moved to Stockholm?

No, Ingrid stayed here.

Okay, so Ingrid stayed here, but you moved to Stockholm and remained there for six years. You left PRIO, which had become an unpleasant place to work. At SIPRI, you continued to pursue your research interests – non-proliferation, disarmament, and heavy water.

Following up on my thesis I first wrote a series of journal articles about economic cooperation – East-West joint ventures. I also studied what happened when things got really tense between East and West, such as with the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. What was cancelled, and at what point did cooperation pick up again?

I published my first journal article on non-proliferation of nuclear weapons around 1974–75. And in liberal Norway, I could be in prison in the autumn of 1974 and be on the Norwegian delegation to the first Review Conference for the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) six months later. Not only was it possible, it all happened quite naturally.

From then on, my research was all about security policy, nuclear arms control, and disarmament, for a long while. Right from the beginning, my interest in the evolving arms control regime had a distinct non-proliferation element, and it was that element that brought me out into the world, to the international jet set on these issues. From there, I widened my scope of research to encompass broader issues of international affairs.

In liberal Norway, I could be in prison in the autumn of 1974 and be on the Norwegian delegation to the first Review Conference for the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) six months later.

Heavy Water

You continued your work at SIPRI during the 1980s, and there you also became interested in the topic of heavy water. How did that come about?

It started a bit earlier, with the establishment of the Nuclear Supplier Group (NSG). The NSG developed a trigger list, i.e. a list of nuclear materials, technology, and equipment that should not be sold, or that one should be cautious about selling, and then only under the international safeguards. In 1977, the NSG added heavy water production equipment to the list, to be exported only under International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards. For the forthcoming Yearbook, it therefore seemed natural to compile an overview of such equipment and of the most important transactions involving heavy water. I visited Norsk Hydro in this connection to investigate what had happened to Norway’s heavy water.

So, were you still at PRIO in 1978, when this work on heavy water started?

Yes, I did this chapter for SIPRI’s Yearbook just before Christmas 1978. Norsk Hydro produced heavy water and had sold some of it to the United Kingdom and France. Later, it turned out that Norwegian heavy water also ended up in other countries, in Romania and most probably in India. But it was only the day before Christmas Eve that I asked myself where Israel got its heavy water from. At that stage, I had a fair overview of the international market and who required safeguards, so I quickly understood it must have come from Norway.

At first, I thought the heavy water had passed via France, because the French helped Israel to build the reactor where the water would be used, and Saint Gobain Technique Nouvelle had designed the reprocessing facility. When I mentioned this in a conversation at the [Norwegian] IFA (Institute for Atomic Energy) [now IFE, Institute for Energy Technology], I was told that 20 tonnes of Norwegian heavy water that was in the United Kingdom but was surplus to British requirements had been withdrawn and sent to Israel. At that time, a company called NORATOM handled the transactions. And so, I put a sentence into the Yearbook chapter: ‘Less well known is the fact that Israel obtained its heavy water from Norway’, marked it in the margin and sent a copy to Viking Eriksen, head of IFA. That set the alarm bells ringing.

Because it was absolutely not public knowledge in Norway that Norway had sold this heavy water to Israel.

No, it wasn’t. And an emergency meeting was convened at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

With you?

I put a sentence into the Yearbook chapter: ‘Less well known is the fact that Israel obtained its heavy water from Norway’, marked it in the margin and sent a copy to Viking Eriksen, head of IFA. That set the alarm bells ringing.

Oh no, not me, but Jens Christian Hauge, [former head of MILORG, the military part of the Norwegian Resistance Movement during the German occupation, later defence minister and leading Labour Party politician] who had negotiated the heavy-water deal with Israel; the secretaries general in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Trade; Viking Eriksen; and maybe a few others, to prepare themselves for the publicity that would ensue as soon as the SIPRI Yearbook came out.

That was my media debut. It was a crazy ride for a few days, and I learned a bit about how experienced media people could operate. For example, Norsk Hydro’s press officer Jon Storækre rang Dagsrevyen [NRK evening news] before the programme went on air, so that there would be no time to double check with me. He put up straw-man arguments, claiming that I’d said so and so, and that he had to correct it.

So, the Norwegian authorities denied this in the media? Did they claim that you had misunderstood?

What Storækre said was that Hydro hadn’t sold any heavy water, it was NORATOM that had sold it. But I hadn’t said or written that. I was well aware of NORATOM and made my rebuttal later in the evening. The daily Dagbladet had it on the front page. I went to the editorial offices – at that time it wasn’t so unusual to do that to make sure that one would be correctly quoted. When I entered Arve Solstad’s [the chief editor’s] office, he was sat there with some of his collaborators. He seized the initiative and said: ‘You are front page material!’ In the media circus that followed, I had many supporters, including at the IFA and in the press, and I was confident about my case.

But wasn’t this a rather sensational revelation?

It was headline news.

It didn’t really fit with how Norwegians saw themselves. But did the Norwegian authorities continue to deny it? Or did they stop commenting on it after a while? How did it end?

The television news wanted me and the foreign minister, Knut Frydenlund, to debate the issue. Frydenlund didn’t want to, which is understandable. The Secretary General at the ministry also didn’t want to be on the air with me, so we were interviewed separately. He said that Norway had conducted inspections, and that this was allowed for in the governmental agreement with Israel. In practice, the one inspection that he referred to was a visit by Jens Christian Hauge in 1961. He had seen where the heavy water was stored while waiting for the reactor to be operational in a couple of years. Of course, that had nothing to do with international safeguards. Heavy water is supposed to be inspected at the moment it enters the reactor and is put to use. IFA reacted when they heard it – it was a pack of distortions – and phoned me to back me up.

To me, it was always clear that […] the Norwegians knew perfectly well what was going on. Later, when Olav Njølstad examined Jens Christian Hauge’s papers for an excellent book about this towering figure, he found an envelope labelled ‘Heavy water for Israel’.

Many years afterwards there were doubts about whether those involved knew what they were doing. In his fascinating book Strålende forskning [‘Radiant’ Research] about the history of the IFA, the historian and current director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute, Olav Njølstad, wrote that he didn’t believe they did.

To me, it was always clear that since the reactor in question would be run on natural uranium and heavy water and was kept free of inspections, the Norwegians knew perfectly well what was going on. Later, when Olav Njølstad examined Jens Christian Hauge’s papers for an equally excellent book about this towering figure, he found an envelope labelled ‘Heavy water for Israel’. The contents showed, beyond doubt, that Hauge knew what the heavy water would be used for. So yes, they knew, and they thought it was right.

For my own part, let me just add that as the author of a doctoral thesis entitled Norway – Israel’s Best Friend, and as someone who has researched the relationship between Norway and Israel, it’s as clear as the light of day that the Israelis knew what they were doing. They always do. And when the Norwegian authorities allowed Jens Christian Hauge, a passionate supporter of Israel, to participate in the negotiation and inspection, there’s no doubt that this wasn’t about civilian objectives.

Returning as Director

Sverre Lodgaard returning as Director. Photo: Private archives

And so we come to your directorial roles. In January 1987, you returned to PRIO as its new director. On the one hand, this was a break: you got your first directorial post and you became director of PRIO, which had never previously had a director. On the other hand it represented continuity in the sense that you returned to PRIO, your academic home.

I remember it well. I was a young postgraduate when you came back, I was finalizing my master’s thesis on Norway’s attitude to the founding of the state of Israel, and in 1987 I got a doctoral fellowship from the Research Council of Norway. So I know a lot about the questions I’m asking now, because I had personal experience of this enormous change. I remember that there were still staff meetings, and that those of us who were young students, taken together with those doing civilian national service, had a majority at these meetings, so we could vote down one proposal after another, overruling all the permanent researchers, if we felt like it.

Basically, there wasn’t really any governance or control. Everyone could come and go as they liked. You could come to work in the weirdest clothes. This was the institute that you returned to and that I was working at as a young student. But why did you come back to PRIO?

I’d had leave of absence, initially for two years. Then it was extended for two more, and then another two years. I guess Nils Petter had a hand in it. A moment ago, we talked about the conflicts of the late 1970s. All the time, in spite of the controversies, I was conscious of the quality of Nils Petter’s research and his importance for the institute. When the fall-out from the famous report occurred, I was already on my way to SIPRI, but with a dual mind of what had happened. The detrimental aspects were obvious, but so were Nils Petter’s importance for the institute. Perhaps it was the case that he also saw value in keeping me within the PRIO family, by ensuring that I got an extraordinary leave of absence. PRIO’s administrative secretary (in fact administrative director), Tor Andreas Gitlesen, came on visit to Stockholm and explained that the egalitarian salary system and the flat structure were about to be abolished, and I decided to return to PRIO.

But wasn’t this a condition you imposed in order that you would return? Or was it the case that people at PRIO realized that they had to go through these processes in order to get you back?

I’m not quite sure about the answer. What came first. My memory isn’t good enough. But I wouldn’t have come back if there hadn’t been a green light to abolish these arrangements.

As far as I remember, at any rate, a very clear opinion was expressed that this had to be sorted out. In other words, you weren’t prepared to come back and start off with lots of negotiations and arguments about the flat structure and the salary system. So if you were to come back, it had to be clear that you would start with a clean slate.

That’s right. I wanted to implement a clean break. It had to be sharp and clear-cut. A lot of things had to happen more or less simultaneously. We’ve talked about the salary system and the governance structure, but there was also the research programme and how we structured and issued our publications. And we had to find new premises. Rådhusgata was unbearable. All of that simultaneously.

I said in a farewell address to you in 1992, when you left your directorship of PRIO, that PRIO under you in those five years had been on a road from anarchy to dictatorship. Then I corrected myself in the speech, and said that perhaps it was enlightened absolutism.

I think at this point I ought to note that I was your successor. In other words, you chose me to take over as the director of PRIO. And it’s for you to say whether you regret that or not. But I was certainly very close, both to you as director and to the changes that occurred. But I would like you to say something about – and this is part of the story –whether it was necessary at times to be pretty uncompromising in order to implement these major changes.

A New Era of Normalcy

Sverre Lodgaard fishing during his time at PRIO. Photo: Stein Tønnesson

This must have been the one and only time I felt I had to be uncompromising on many basic issues at about the same time. I did things that weren’t normal, things I wouldn’t have done under other circumstances. But then, the situation at PRIO wasn’t normal either.

Among the things I mentioned, the salary system was the easiest to put in place. The decision had been made. We would go back to the usual for research institutes. As for the governance structure, that too had been decided: the flat system would be abolished. But then a new one had to be introduced, and things like that do not function properly overnight. It takes time for a new set-up to be up and running and operating smoothly.

PRIO hardly had anything that deserved to be called a research programme. There were diverse projects. We had to establish some priorities. PRIO was a small institute at the time, so resources had to be concentrated around a few main programmes. Some projects had to go. There was no future for women’s studies as a separate branch of research, or terrorism for that matter. Some of these conversations were uncomfortable, in particular because people realized that a new era was in the offing and they were looking forward to being part of it. When they were told ‘no, we cannot accommodate you’, it was painful. Understandably, some reacted with disappointment and bitterness.

In addition, the office building at no. 4 Rådhusgata was an unpleasant place to work. The noise level was unbearable. There were heavy vehicles driving past right outside, making the building shake. There were exhaust fumes and huge amounts of dust and dirt. In some offices, it was difficult to hear what people were saying on the phone. So, what could we do about that?

I heard that the university department of anthropology had its eye on no. 11 Fuglehauggata at Frogner, but that they hadn’t signed a contract yet. No doubt the anthropologists would describe what followed as overly offensive on my part. And in a way it was. I phoned Jens Kristian Thune, a top lawyer, and asked him to assist. I knew him from my time in the Student Association, even though he belonged to an older generation.

Thune had hunted down the hidden fortune of shipowner Hilmar Reksten and secured NOK 600 million for the government, and was an important figure in Norwegian public life for a generation. ‘What is it?’ asked Jens Kristian. ‘It’s about using a sledgehammer to crack a nut,’ I said, and explained what I was after. He said ‘Okay, I’m on board.’ So we negotiated with Veidekke, the company that owned the building in Fuglehauggata. I conducted the negotiations on our side, as is usual in such situations, with Jens Kristian as my coach. He didn’t have the time to discuss with me in advance – we did it in the car on the way to the meetings. He was utterly professional, making the right compromise proposals at the right moments.

So you bought no. 11 Fuglehauggata?

We rented it. We laid claim to most of the building and offered the rest to the anthropologists, who turned it down. Instead, social scientists from across the street moved in. We sold Rådhusgata for NOK 10–11 million, and Jens Kristian’s help was invaluable in that phase too, as I had no experience in making such deals.

We used some of the money to refurbish Fuglehauggata and adapt it to our needs, but as far as I can remember we were left with NOK 7 million or so. Foundations are legally obliged to have sufficient reserves to cover the salaries of all employees for three months in case they have to close down, and a solid reserve is a dear asset anyhow. This was a major operation. Just the fact that we got away from Rådhusgata made most people positive about the overall plan.

Did you say dictatorship? Yes, I didn’t see any reason to debate whether it was acceptable for representatives of PRIO to go around in workmen’s overalls, making visitors wonder. There had to be a minimal dress code.

Yes, so did you just say that? I’ve never been reprimanded for my attire, so I wonder how you went about it?

Well, I must have said something.

I wonder how you dealt with this? Do you remember?

I don’t. Maybe it was a case of people picking up signals. People were happy to get away from what had become a negative feature of life at the institute.

Perhaps it’s not necessary to say that much about it. Because when we moved from the old offices in Rådhusgata to the new offices in Fuglehauggata, which we thought were really posh, there was such a big shift in the level of office facilities that perhaps people didn’t feel it was that natural to go around in all kinds of swimming trunks and without shirts and so on, as had been completely commonplace at Rådhusgata.

So perhaps this contributed a little to the upgrading of dress and other things. And of course you didn’t look like a radical yourself. You made sure you wore smart clothes and a jacket, sometimes even a suit, to work. I certainly hadn’t seen that before in Rådhusgata.

The Punching Machine

But this developed of its own accord – one thing led to the other. I also wanted to have an overview of people’s whereabouts. It hadn’t been like that before. People came and went more or less as they liked. I installed an item that was current at other workplaces at the time – a punching machine, to register presence and absence – something that wasn’t used only in private companies, but also in the public sector. But I would never have thought of introducing such a thing if it were not for the need to ensure regular presence at the workplace. I realize it must have seemed like some kind of shock therapy.

You can say that again! Because you didn’t engage in any in-depth or broad consultation about the punching machine.

I didn’t, but I should have done so, with the trade union.

I remember arriving one morning and there were five, six, seven researchers standing around a box on the wall, which had been nailed up by the director, and I remember asking, ‘What on earth is this?’ I hadn’t seen anything like it before in my life. And there was silence, I think because we didn’t know whether we should smile, get angry, or react, because the shock effect of the clocking-in clock was pretty instantaneous.

Yes, precisely.

But did this cause any fuss? I remember I clocked in and out quietly.

No, there wasn’t any fuss. Today, arrangements are much more onerous. People have to keep timesheets. A much tougher measure. But at least I achieved a degree of order, ensuring that the staff would be present during working hours. To sum it up, the changes were about getting the institute into such a state that we could receive visitors without embarrassment and without being the object of unpleasant and negative attention.

On another level of respectability, I remember that when I was interviewed by Jarl Munch from NRK (Norwegian Public Broadcasting) upon return from Stockholm – Norway wanted Israel to return heavy water – I was made to understand that NRK had not been in the habit of dealing with PRIO. PRIO was ignored. I also knew there were MPs who were sympathetic towards PRIO, but who in light of what had happened had tried to deflect attention from the institute, keeping it out of the limelight so that the annual funding could continue.

But you were planning to put more in place? You had become the director. The institute’s Board, as it was christened, was technically an advisory organ for the director, with the exception of the appointment of future directors, where the Board had real power. You needed a Board with appropriate authorities, much the way other institutes functioned. Hadn’t that happened at PRIO before? At least it hadn’t worked out. So how did you do this?

My impression was that the Board had gone along with things, with the flat structure and the salary system etc., even though I doubt that they could have imagined something similar at their own institutions. I saw the board as passive bystanders. I phoned around to find a new chair. And I got no, no, no, no.

Anders Bratholm, no. He had been in the circle around Johan right from the start. But Anders also had merits from the war, as a member of the resistance, and for what I know his refusal may have been linked to the court case against Nils Petter.

Finally, Bernt Bull accepted, after discussing the matter with Knut Frydenlund. Bernt Bull had been political adviser at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs when Frydenlund was foreign minister. He belonged to that rare breed of Labour Youth League (AUF) members who were both teetotal and pro-NATO.

Trygve Ramberg also deserves a mention. He was chief editor at Aftenposten and affiliated with the Liberal Party (Venstre). He and I talked a great deal about how to get PRIO back on track. Trygve was a great man and an invaluable advisor.

And when PRIO moved to Fuglehauggata in the autumn of 1987, did you want to have some kind of opening ceremony?

Yes, to mark new times. Knut Frydenlund had passed away and the new foreign minister, Thorvald Stoltenberg, attended. Thorvald lived up to expectations in his well-informed and customarily elegant manner.

And contributed to making PRIO more reputable? Because wasn’t this what it was about?

Exactly – I think the staff felt that he conferred a sense of confidence in what we were trying to achieve. We had taken important steps on the research programme and the governance structure. The first budget from the Ministry gave a boost – an additional NOK 1.6 million – covering the rent for Fuglehauggata. That was encouraging.

We didn’t expand massively during my term as director, but the budget was doubled. I took guidance from the way things were done at SIPRI. While important decisions had been made – we talked about that – there was still a lot that needed to be put in place. The new Board was supportive. But even so, it took time to streamline the new set-up and get people used to it.

Another example: all SIPRI’s books were published by Oxford University Press. A large, well-reputed publishing house. I wanted a similar arrangement for PRIO’s journals and books, and invited half-a-dozen British publishers to make bids. I wanted our most important publications to be with one publisher: books, the Journal of Peace Research and what became Security Dialogue – formerly the Bulletin of Peace Proposals. In the end, SAGE made the best offer. Both journals and two or three books each year in a book series.

Not to forget or belittle: some staff members had difficulties getting the new governance structure running in their veins. If they mobilized enough, they might have their way. I struggled a bit there. We had to allow for the new structures to take root over time.

So was this the thing you found most difficult?

In any event, it was the administrative matter I worked on the longest.

Opposition from a New Angle

Sverre Lodgaard. Photo: Private archives

Can you remember the areas in which the resistance was greatest, or where it came from? I think I remember that in the beginning, as you said as well, there was a kind of relief. People were eager for things to be a bit more orderly here. But resistance developed as time went on. Do you have any memory about which areas this came from?

Yes, I do have some. I invited Johan Galtung to give lectures on major topics of peace research. Håkan Wiberg, too, another leading scholar in the field. After a while, Tor Egil Førland came to me on behalf of young historians – we were fortunate enough to have five or six at that time, including you, Stein [Tønnesson], Førland, [Nils Ivar] Agøy and Olav Njølstad, who was doing his civilian national service and acted as my assistant for a while. A very strong group.

Tor Egil said that if I did more of that, the group would consider it a step backwards for PRIO. And it wasn’t just you historians, there were also others who were less than enthusiastic and didn’t turn up. They said that they had heard Johan speak so many times before that it wasn’t all that interesting to listen in once again. I disagreed, because I thought Johan was constantly producing new material. Here we had an interesting clash of scholarly opinion. I yielded and ended the lecture series in light of the reactions and because the lectures were under-attended.

On a related issue: I spent some time preparing for the 60th birthday celebration of our founder. It was the proper thing to do – besides, it was part of my job to show Johan the attention he deserved. He appreciated it. He rang me the next day and said that he and Fumi had talked about the event and had found it better than a comparable event for Arne Næss. That was kind of his yardstick.

I remember that Tor Egil and I sat at the back for that 60th birthday celebration, because first we had a lecture by Johan Galtung himself, and then we had a dinner at the Norwegian Institute for Social Research. And I remember that I was almost a bit in shock over Johan Galtung’s speech at that so-called seminar. Because he made a thunderous speech about the role of the United States in the world, which he didn’t have anything particularly good to say about. I remember I’d been at several of these seminars, but the icing on the cake was this long speech he gave at his 60th birthday celebration.

You’re completely right. At that time, he was giving a series of lectures on the international role of the United States, about overt warfare, about so-called covert actions by the CIA and so on. And this was a broadside. There was no Q&A after that lecture, so we went straight over to the Norwegian Institute for Social Research where the party continued, and where I gave a short speech praising him i.a. for his courage. I had always found his courage impressive. However, he didn’t see it that way himself – belittling himself, I thought, which was otherwise not his habit.

Let me mention another matter, about productivity and the conduct of research projects, which was conflict-ridden and unpleasant. I asked a couple of staff members to show what they were doing, as they had not published much for a while. In response, they presented a book outline that they claimed was very promising and that they had busied themselves with for quite a long time, but nothing ever materialized. They hadn’t written anything. That was painful. I was quite annoyed and did not hide it.

At PRIO that was really a new development. That someone would actually require their fellow staff members to produce research, and if we hadn’t done it, whether we were students or doctoral fellows or researchers, then Director Lodgaard would say, ‘We can’t have this.’ It felt – and of course it was – very different, and it made an impression. And many people felt that they were coming up against a director who was making demands. Some people thought that was fair enough, while others thought it was unreasonable.

Yes indeed – some came to me and said I had been unreasonable.

Of course, it’s part of the picture that this was something new. Because before, down in Rådhusgata, if one had been a master’s student there for five years and not produced anything, one could still wander around in shorts with no shirt and it was no problem.

But that was no longer the case once we came to Fuglehauggata. And it was very clear that we were now in a new era. But fundamentally, was there an acceptance that this was necessary and that this was a new era?

Yes, that was certainly my impression. That there was acceptance. Colleagues came not only to convey discontent, there was more support, and I felt that very clearly. No doubt there were a few hangovers from the flat structure. That’s something you just have to understand, it’s human. I understood there was something there lingering on, but ultimately it disappeared.

And within this process, from when you returned in 1987 until 1992, there were members of staff who weren’t allowed to stay at PRIO. Because wasn’t there a streamlining of PRIO in all areas?

Programme priorities and concentration of resources meant that some had to leave. I had bad feelings about it, but there was no way around it. For much of the rest – ordinary working hours, presentable working conditions and so on – the streamlining you mention was a transition to normalcy. It was so obvious that there was no reason for lengthy discussions. The shortcut, cutting straight to the chase, was the right way.

And so it’s not unreasonable to characterize the five years when you were director as a path from virtual anarchy, i.e. chaos, to a dictatorship or enlightened despotism? There was really no doubt about who was in charge now, steering the PRIO ship, sometimes with measures that were harsh and direct?

But you know, when you shoulder the director’s responsibilities, your perspective becomes a bit different. I felt that ever so often it was me who had to back off. I had my doubts, not so seldom, about what was going on, but found it best to let it pass. Much depends on your vantage point.

Leaving PRIO for UNIDIR

During your second three-year term, it suddenly became evident that you were going to leave PRIO prematurely, in 1992. I remember that we were very surprised. Why?

I was pretty content, to be honest, with how things were going at PRIO. In essence, I felt I had done what I wanted and what was expected of me. PRIO was in good shape, with a good staff, and in that sense I felt free to leave. And then a job came up that I was interested in. I applied, or rather Norway put me forward as a candidate, for the role of director of the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, UNIDIR, in Geneva.

Johan Jørgen Holst was foreign minister and did much to support my campaign. Bjørn Skogmo in Geneva, Martin Huslid in New York, and Bjørn Kristvik on the Board of Trustees likewise. Thanks to their efforts, my candidacy succeeded by a clear margin. The Board had 20 members and only two of them voted for another candidate. So, I moved to Geneva and stayed there for just over four years. It was a new horizon opening up, which brought me to all the main regions of the world.

These were good years, and there were some difficult times as well. UNIDIR’s Board of Trustees was also the UN Secretary General’s advisory board on security and disarmament and I was involved, first in an ex officio capacity, and then as an elected member up until the new millennium. At first under Boutros Boutros-Ghali and then under Kofi Annan.

But were you tired of being director of PRIO and thinking that now you would look actively for something new? Or was it the case that PRIO was getting into good shape and you had actually planned to serve out your term, and then this job turned up? Or a bit of both?

It was mainly pull, not push, and I felt free to leave. I was approached from Geneva and encouraged to apply.

So there wasn’t any plan?

No, there wasn’t any plan. An opportunity turned up. I could have stayed on, but then it was exciting to do something new. And I wasn’t yet 50. So there was time for new adventures.

Exactly, and then you were in Geneva until 1997, before returning once again to Norway as the director of NUPI (Norwegian Institute of International Affairs), PRIO’s – how should I put it – partner and competitor, for 10 years from 1997–2007. Was that a plan?

Sverre Lodgaard as Director of NUPI in 2007. Photo: Terje Bendiksby / NTB scanpix

Returning as Director of NUPI

No, there was no plan there either. [Nobel Institute Director] Geir Lundestad, who was chair of the advisory board at NUPI, phoned and said I ought to apply for the job. My new Swedish wife Marianne [Lodgaard] and I – we got married in 1994 – discussed what to do: continue to live abroad or move to Norway? She didn’t have a full-time job in Geneva – it was difficult for spouses to get jobs there – just a part-time engagement at the Swedish school. So we decided to move to Oslo. Marianne got a job almost immediately at the WWF (World Wildlife Fund).

Around 1990 the world changed, profoundly, and after a while there was little difference between PRIO and NUPI. They complemented each other, and to date there’s been no conflict to speak of between these institutes. Still, NUPI was different from PRIO. Giving clear signals is important everywhere: research is the main function and a smooth-running administration is important to facilitate it. At PRIO I had looked for the right person to head the administration, in fact I made several attempts. Terje Bruen Olsen spent a year on a clean-up operation and did a great job, but it was only when Grete Thingelstad arrived that things fell into place.

At NUPI, the relationship between the permanent researchers who had always been on the government payroll, and those who had been recruited on a project-by-project basis, was delicate. The parameters were changing: now the permanent staff also had to make project applications and contribute to the generation of revenues.