In December of last year, the Chinese state jailed a physician in the city of Wuhan. His crime? Attempting to warn authorities against the occurrence of a potentially contagious and deadly new virus. The physician, Dr. Li Wenliang, has since died from the same disease whose spread he tried to contain.

A funeral in May 2020 in the favelas of São Paulo. Photo: Léu Britto | @fotovielas

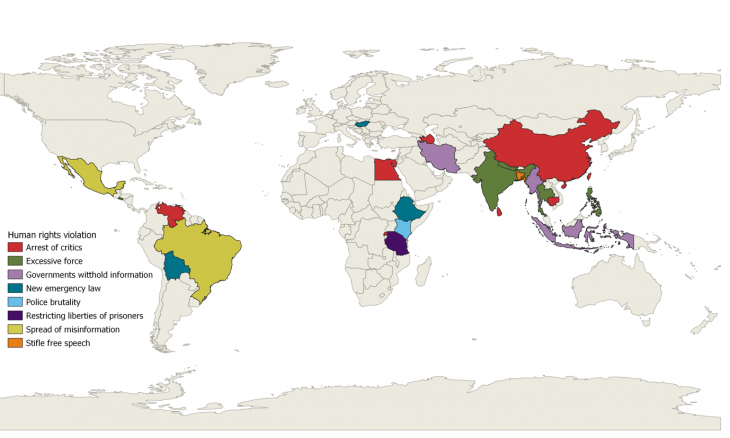

This established a pattern. As the coronavirus and the COVID-19 disease spread, regimes across the world responded by attacking and arresting critics, violating human rights, and by imposing unchecked and draconian emergency laws. The contagion is shown in the map below. Toward the end of March of this year, Human Rights Watch noticed the disturbing pattern. Across South-East Asia, in countries such as Cambodia, Philippines, Thailand and Myanmar governments were actively taking advantage of the coronavirus pandemic to crack down on critics, in the process curtailing core civil and political liberties.

Tracking Governments’ Responses

Since March, PRIO has attempted to track and monitor such government actions and we have built a database that now allows for some very preliminary discussion. This database is necessarily limited. For one, this is ‘live’ tracking; we have not had the time and resources to go back to check and double check each and every report as we would if we were producing a standard dataset.

Internationally, democratic stalwarts are preoccupied with their own problems and concerns and have limited bandwidth to either sanction human rights abuses or support pro-democratic forces.

Perhaps more importantly, what we have been able to compile necessarily only represents a portion of actual cases. To track and monitor coronavirus-related human rights abuses we rely on media reports. The attention of the media is, quite understandably, focused on the actual pandemic. That, combined with restrictions on movement in general as well as the very efforts of governments to stifle free speech we document, is likely to bias our sample downwards. That is, we are most likely missing important events. With these caveats, we here present some tentative findings.

It is, of course, nothing new that regimes take advantage of events to secure their position or extend their power. Democratically elected regimes do that probably just as often as autocratic regimes. Often, this is completely legitimate, such as a democratically elected government calling a new election when times are good, and the economy is booming. It is also perfectly legitimate, though of course also debatable, that many democratic regimes have used emergency powers granted them within existing laws or enacted limited emergency laws to deal with the coronavirus pandemic.We have compiled a database of government actions linked to the coronavirus epidemic that constitute human rights abuses, curtailments of core civil and political rights, and/or extra-judicial actions. Our definition is quite broad but still excludes most of the measures enacted by most governments in response to the pandemic. We have tried to differentiate between legitimate and illegitimate actions as well as ‘normal’ taking advantage of circumstances and more malignant efforts. Many of these decisions are necessarily subjective, adding another caveat to the list above.

But there’s also a long tradition of undemocratic regimes using events to extend or secure their hold on power. From the infamous Reichstag Fire Decree that marked the end of German democracy, to the 30 year-long ‘emergency’ law-rule of Hosni Mubarak, we can now, sadly, add several attempts by governments to use the coronavirus to suspend democracy. As a consequence, the world will emerge from this pandemic less democratic and less free than it was when it all started.

Eight ways to sacrifice human rights

Governments have, as always, shown great ingenuity in figuring out how and why human rights have to be sacrificed in order to fight the pandemic. As such, we have put efforts into eight different categories: arrests of critics, excessive use of force, intentionally withholding information, enacting new emergency laws, police brutality, restricting liberties of prisoners, spreading of misinformation, and stifling of free speech.

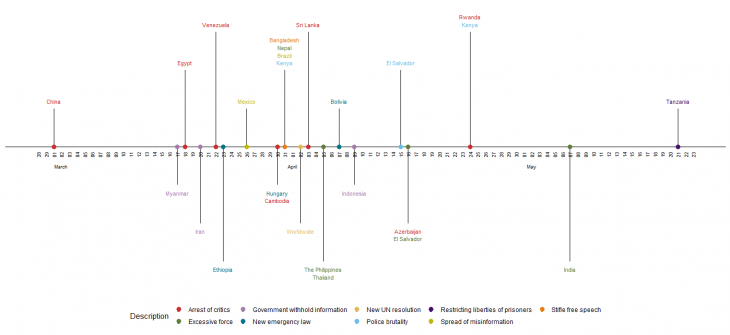

Figure 1.

A timeline of such actions is shown in Figure 1. It marks when something happened, what country, as well as what category of actions it belonged. We see a flurry actions in particular concentrated within the month from mid-March to mid-April. After this we have seen much fewer specific actions, though this may very well change as the pandemic moves around the globe.

It is maybe not surprising that so much happened within this four-week window. This is the period where the global awareness of the grave risk the pandemic confronted all countries with really took hold. We would expect, and could even to a large extent forgive, some government missteps as well as over-reactions in this window. Early efforts to downplay the risk of the pandemic, including arresting critics, would fall within the scope of such actions.

Beyond this, however, we see that governments did not attempt to rectify past missteps. Instead, they have doubled down on the use of force and human rights abuses in their response to the virus. We also see governments, most famously the Hungarian, that enact emergency laws with little or no limits on scope and with no expiration date. These actions have had some almost tragically comic results: while Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil has downplayed and ridiculed the pandemic, criminal gangs have instead stepped up and are enacting measures to prevent contagion.

This pattern, of democratic backsliding and a tightening of the autocratic screw, we know from the past. Autocrats and wannabe dictators can use precisely these tools to undermine existing institutions and secure their own power. Once more firmly secured, these powers are hard to take back. Unfortunately, this means that the world will be less democratic after the coronavirus then it was before.

What now?

This process is unfolding just as the two most important countervailing forces are absent. On the home front, the ultimate guardians of democracy and civil liberties, people united in the streets, are at home. Either under complete lockdown or under restrictions on freedom of movement or assembly. Consequently, mobilizing against the government, a task that in the best of times is hard and dangerous, is now even more daunting.

Internationally, democratic stalwarts are preoccupied with their own problems and concerns and have limited bandwidth to either sanction human rights abuses or support pro-democratic forces. The UN Security Council is in deadlock, and even if it wasn’t, the current dynamics of the Council almost guarantee that anything relating to defending democratic institutions will not be seriously considered.

This, to a large extent, leaves us looking to the broader UN and the big family of UN agencies. Ever since the passage of the Sustainable Development Goals, and especially SDG 16, the UN has had a clear mandate to support and defend ‘inclusive, accountable, and just’ institutions. If there ever was a time we needed the UN to step up to that challenge, it is now.