Wenche Iren Hauge exploring the mine (clearance) field in an LTTE-controlled area in northern Sri Lanka, 2004. Photo: Private archives

In my experience, successful peace processes are marked by close interaction between actors who engage with the process for a long time, know the conflict and the parties well, and gain their trust. Trust is more important than anything else. The long-term actors might be from NGOs or from civil society. They certainly don’t have to be people from political circles. They are vitally important in the first, most difficult phase, when the process is vulnerable, and trust is gradually built. This creates a foundation for the UN to play a role in later stages. The UN is a large apparatus, and when it enters a process, the dynamic is immediately changed. However, at some point it is often necessary to have UN agencies on board, not least when a peace agreement has been signed, in the demobilization phase, when there is a need for monitoring, and when it’s time to disarm non-state actors and organize the surrender of weapons. At this stage, the role of UN agencies can be critical.

Wenche Iren Hauge, interviewed by Åshild Kolås

Åshild Kolås: Before you started working as a researcher, which life experiences were the most decisive for your choice of studies, and what led you to your career path?

Wenche Iren Hauge: Travelling abroad had a major impact on those decisions, but I should probably start out with a brief summary of my life prior to travelling, to put those travels into context. I was born in 1959 in Ålesund district hospital, since my family lived on the island of Valderøy, just outside of Ålesund on the west coast of Norway. I attended primary and secondary school at Valderøy, and went to high school at Fagerlia in Ålesund.

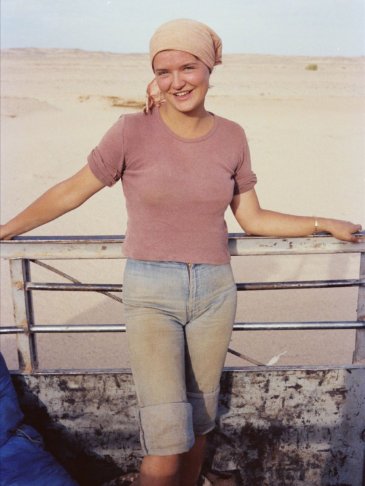

Wenche in the Sahara desert south of Tamanrasset, 1978. Photo: Private archives

When I was about to finish high school, I was eager to travel. One day at the library in Ålesund, I saw a poster announcing something called The Travelling Folk High School (Den reisende folkehøyskole). The poster explained that students at this school would travel abroad to learn about the world, and study at the same time. This was in 1978, and the school had just started up in Norway. As soon as I saw the announcement, I wanted to attend. The school year was scheduled to start in August, after the summer holiday, and the journey was to begin in the autumn of 1978 and continue into the winter of 1979.

The admission process took place at The Experimental Highschool (Forsøksgymnaset) in Bærum, Oslo’s western suburb. We had to go there in person and have a conversation with the staff. This was how we were admitted. The school itself was located at Hankø Fjordhotell, a hotel outside of Fredrikstad, on the eastern side of the Oslo fjord. We stayed at Seilerkroa (The Sailor’s Inn) and the Yacht Club for three months before we started the trip. There were one hundred students all together. Fifty of them would go to Asia by bus, and the other fifty to Africa.

A Bus Journey to Africa

I was among the fifty travelling to Africa. We bought five old buses and were divided into five groups. Each group would live in their own bus throughout the school year. We drove through Europe all the way to Sicily and took the ferry across the Mediterranean to Tunis. From there, we continued into Algeria and through the Sahara Desert with our buses, well loaded with water and diesel and whatever else we needed.

The Travelling College buses struggling to advance in the Sahara desert, 1978. Photo: Private archives

We also brought with us some clothes that we had collected at a flea market. We gave these clothes as gifts to the liberation movement Polisario, which was fighting for an independent Western Sahara. Algeria supported these freedom fighters, so Polisario had several offices in Algeria and refugee camps in Tindouf. The clothes and some protein biscuits we had baked ourselves were delivered to the Polisario office in Algiers. Then we travelled further southwards, where our buses parted ways. Some travelled all the way to Nigeria, and my bus was one of those. Others drove through Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), the Ivory Coast, and so on.

This was my first trip outside Europe. It made a strong impression on me to see the bottomless poverty in some countries, especially Niger, where children came forward to the bus, many with the eye disease Tracoma. In some areas there was very little food available. At the same time, we also saw the contrasts. In Nigeria, for instance, rich elites lived in luxury and others in extreme poverty. Multinational companies had invested in the Nigerian oil industry, and they had their own huge complexes with golf courses, swimming pools and other luxuries. This was an eye-opener for me. In addition to travelling, we read up on the countries we visited. The reading list included books about colonial history and imperialism. I became aware of the differences between the rich world in the North and the poor world in the South, and how these two worlds were connected, historically and today.

In Nigeria, rich elites lived in luxury and others in extreme poverty. Multinational companies had invested in the Nigerian oil industry, and they had their own huge complexes with golf courses, swimming pools and other luxuries. This was an eye-opener for me.

When we returned to Algiers, one student was allowed to travel to the Polisario refugee camp in Tindouf together with one of the teachers from our school. I was the lucky one since I knew a little French. Seeing the refugee camp also made a strong impression. I saw how the refugees lived in tents, out in the desert, under miserable conditions. And let’s not forget that this conflict is still ongoing today. Polisario is still there, demanding an independent Western Sahara.

Wenche with a group of Algerian soldiers in the Sahara desert, 1978. Photo: Private archives

Travelling by Train to Latin America

When I returned to Norway, I lived in Oslo and worked for a year as a nursing assistant at Ullevål hospital. This was a way to save money for my next trip, which was to Latin America. I started by flying to the United States with my family. We drove across the United States from New York to San Diego, California. From there, I travelled by train through Mexico, and later to Central America. This was in 1980, and both Guatemala and El Salvador were in the midst of civil war. It was a year after the Sandinista revolution took place in Nicaragua. I travelled for a full nine months, so I had plenty of time to see the situation in these countries with my own eyes.

Guatemala was the country that left me with the strongest impressions. The Guatemalan civil war had started twenty years earlier, in 1960, but in 1980, the conflict was escalating. I learned later that Mayan Indians and poor Ladino farmers were massacred in 440 documented incidents of violence carried out by the Guatemalan army. Most of these massacres took place in northwestern Guatemala and in the county of Quiché, where the hometown of Nobel laureate Rigoberta Menchú is located.

Guatemala was the country that left me with the strongest impressions. […] We had to get off the bus every time the military stopped us to search the passengers. The soldiers often took local people away from the bus, and we could only guess at what happened to them.

The main guerrilla group in Guatemala was Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (URNG), which fought against the military dictatorship. URNG had a programme of land reform, economic equality, and improving the living conditions for the Maya population. I travelled around the country in local buses, and experienced daily life firsthand. We had to get off the bus every time the military stopped us to search the passengers. The soldiers often took local people away from the bus, and we could only guess at what happened to them. Large numbers of people disappeared and were tortured at the time.

The same was the case in El Salvador, where a full-blown civil war was going on. I travelled through El Salvador to Nicaragua, which was a great contrast. Young Sandinista leaders greeted people at the border, many of them women. They stood at the border crossing to welcome everyone into Nicaragua. They also wanted to inform us about the literacy campaign they had launched.

During this trip, I learned more about internal conflicts and became interested in understanding their causes. I had seen the poverty, lack of democracy and persecution that led people to join the guerrillas. At the same time, I knew that the United States supported several of the military regimes in Central America. I also reflected on the differences and similarities between these conflicts and the experiences I had from Africa, where I had learned a lot about unfair international trade relations and the consequences of multinational foreign investments. I became interested in the internal dynamics of civil wars, and also in how international actors influence these wars. When I returned to Norway, I started studying political science. If conflict studies or international politics had existed at the University of Oslo at the time, I would probably have chosen one of those disciplines. But it was difficult to find a better fit for my interests, so I ended up studying political science.

Unsatisfying Theories

What was it like to return to Norway after so many impressions during your travels, and attend much more theoretically oriented university courses?

It was not very satisfying, to put it mildly. When I started political science, the curriculum contained a lot of organizational theory and democracy theory with hardly any reference to Third World countries. The course drew on a Western academic understanding of how democracy works or should work. Later on, I had the opportunity to take a course in international economics, called ‘International Economic Politics’. It made a better fit for my interests, because there was more focus on systemic inequality and structures in world trade that put Third World countries at a disadvantage. But to begin with, there was an enormous gap between what I was given to read and what I had seen with my own eyes. I had a hard time trying to rediscover the reality I had experienced on my travels.

A Well-Intentioned but Failed Peace Treaty

How did you start your career at PRIO?

Wenche in the Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding Programme at PRIO, 2008. Photo: PRIO

That happened when I was writing my master’s thesis. I decided to write a thesis on Esquipulas II, a Central American peace treaty from 1987. Esquipulas is the name of the Guatemalan city where the treaty was signed. The treaty involved all the five countries of Central America: El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Costa Rica. It was a peace agreement that was meant to end the internal conflicts, and also bring peace between the five states. It was intended to start dialogues inside these countries and stop the practice of supporting guerrillas in neighbouring countries, such as the Contras in Nicaragua. The Esquipulas II agreement was signed in 1987, but in 1989 there was no peace in Central America at all. The agreement was not a success.

I thought this was a great topic to focus on, because it would allow me to research the internal conditions in each country, as well as the relationship between the countries, and even the role of external actors such as the United States. I wanted to return to Central America to gather material for my thesis, and was able to stay for a few months at Consejo Superior de Universidades Centroamericanos (CSUCA), the Central American University (CSU) in San José, Costa Rica. I stayed there while continuing to work on my thesis.

The title of my thesis was ‘Obstacles to the Fulfilment of the Central American Peace Plan’. I had Kjell Skjelsbæk as my main supervisor. Kjell Skjelsbæk was a prominent former director of PRIO who, after holding a position at the Institute of Political Science at the University of Oslo, had joined the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), where he also served for three years as director. When I returned from Costa Rica to Norway to complete my thesis, Kjell Skjelsbæk was seriously ill with cancer. He made an incredible effort to offer me the best supervision he could. It was absolutely amazing, and I was extremely grateful. I had applied for a grant at PRIO, and stayed there while writing my thesis. Hans Petter Buvollen at PRIO was my second supervisor. Sverre Lodgaard was the director of PRIO at that time. This was my first encounter with PRIO.

The North/South Coalition

After finishing my studies, I looked for work. The North/South Coalition (Idégruppen om Nord/Sør) announced a vacant position as Head of Information. I applied and was offered the position. The North/South Coalition was a debate forum for politicians, academics, NGO staff and the media, with a focus on North/South issues such as trade policy, debt crisis issues and development aid policies. I was the only employee of the North/South Coalition.

The board of the North/South Coalition included Bernt Bull from the Labour Party and Odd Jostein Sæter from the Christian People’s Party, both members of the Norwegian Parliament (Storting) at the time; Kalle Moene and Grete Brochman, who both taught at the University of Oslo; Jens Andvig, who was a researcher at NUPI; and Elin Enge from the Forum for Development and the Environment, an NGO. In short, I was working for a very resourceful group of people. This gave me an excellent opportunity to work on North/South issues.

It was an important learning experience for me. While I was the only employee, the North/South Coalition had a coordinator, on rotation. When I started my job, Øystein Tveter from Diakonhjemmet International Centre (DIS) was the coordinator. He was a highly skilled coordinator who worked hard to put key issues related to relations between the Global North and South on the policymaking agenda and raise public debate and awareness on north-south issues. I was inspired by his enthusiasm and fearlessness. Diakonhjemmet International Centre was the host institution for the North/South Coalition when I started the job. However, this only lasted a few years, as we only spent some years at each institution that hosted the Coalition.

After a short while at the Centre, it was time to move. This happened to be just at the time when Dan Smith became the new director of PRIO. Bernt Bull invited Dan to join the board of the North/South Coalition on behalf of PRIO, and Dan agreed. Soon after, Øystein Tveter and Bernt Bull also asked Dan to arrange for PRIO to host the Coalition for the next two-year period. Dan agreed to this as well. The North/South Coalition moved to PRIO, and I was based at PRIO as the Coalition’s Head of Information. This was how I came to PRIO (the second time).

Working with Dan Smith

I had a very good collaboration with Dan. He held a great interest in all aspects of international relations and had no issue with incorporating North/South relations and related political and economic challenges into his conflict and peace orientation. I learned a lot from him. When it was time for the North/South Coalition to move again, there was a vacancy as a junior researcher at PRIO. I had enjoyed my time at PRIO and my interactions with its research community, so I decided to apply for the job. It was in a project called ‘Dynamics of Conflict Escalation’. I applied and was offered the position.

The objective of the project was to test conflict theories with quantitative data. So, I had to work quantitatively, which I was less used to. I worked closely with Tanja Ellingsen [at PRIO until 2012] on this project. As it began to draw to a close, Dan asked me whether I had considered applying for a doctorate. I started to think about his suggestion and concluded that it might be the way to go if I wanted to continue a research career and delve into the topics that interested me. I applied to the Research Council of Norway (RCN) for a PhD grant and was successful, and so the PhD project was funded from the RCN’s Poverty and Peace programme.

Fieldwork in Haiti, 2015. Photo: Private archives

In addition, Dan submitted an application on my behalf to the Ford Foundation, and I got additional funding for the doctoral project, which had the title ‘Causes and Dynamics of Conflict Escalation: The Role of Environmental Change and Economic Development, A Comparative Study of Bangladesh, Guatemala, Haiti, Madagascar, Senegal and Tunisia’. This was a huge comparative project where I had selected the cases on the basis of the quantitative study I was about to complete.

For the comparison, and as I was looking for the importance of lacking economic development as a potential cause of conflict, I selected countries with different levels of economic development. I chose two conflict countries that were low-income and two that were lower middle-income, and in addition two peaceful countries of which one was a low-income and one a lower middle-income. When I started the project, these two latter countries remained peaceful, although the situation changed somewhat later, unfortunately.

Explaining Peace through Systematic Comparison

What were your conclusions on the peaceful countries?

The cases were systematically selected. The two peaceful countries were Tunisia and Madagascar. Madagascar was then a low-income country and Tunisia a lower middle-income country. The conflict countries Haiti and Bangladesh were low-income countries, while Guatemala and Senegal were lower middle-income countries. I chose countries with slightly different levels of economic development. In that sense, the quantitative background was useful for the selection process. However, it became clear once I had started on the case studies that qualitative methods, especially fieldwork with interviews, would be my main methodology.

The head of the National Cultural Institute in Antananarivo […] explained: ‘There is a word in our language called fihavanana. It means solidarity. […] If you live in the same area as me, I have a problem hurting you, because we have walked the same road, been drinking the same water.’

I travelled to all the six countries and carried out fieldwork. In the conflict countries, I interviewed actors on both sides of the conflict: from the government side and from the non-state armed groups. In the peaceful countries, I interviewed important actors who had information about political factors and cultural features that might have helped keep the country peaceful.

This was an interesting exercise, especially in Madagascar. I found that socio-economic, ethnic and religious divides often created a fertile ground for conflict, especially where there was a deep cleavage between the economic elites and poor marginalized groups, and when the economic cleavages coincided with the ethnic and/or religious divides and created the deep conflict fault lines. In Madagascar, these dividing lines were not so clear, and identities were partly intersecting.

In addition, I discovered cultural features that contributed to peace, such as a concept known as fihavanana. The head of the National Cultural Institute in Antananarivo, Juliette Ratsimandrava, explained it to me as follows: ‘There is a word in our language called fihavanana. It means solidarity. This idea is transformed into the life of the neighbourhoods. People who live in the same block as you develop some sort of solidarity with you. If you live in the same area as me, I have a problem hurting you, because we have walked the same road, been drinking the same water.’

The interesting thing about this concept was that it was known and respected throughout Madagascar, also in the armed forces. So, through several major political crises in Madagascar, including incidents in the 1970s and 1980s, both the protesters and the police had shown restraint and remained non-violent. The concept of fihavanana was often referred to by those who explained this situation.

Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

You have used both quantitative and qualitative methods in your research. How would you describe your own experience with different methods, and how do you see the significance of methodology for the results of peace research?

I think combining quantitative and qualitative methods can be very good. For my doctoral project, for instance, it was important for the comparative aspect of the study to select the countries systematically. I did this on the basis of quantitative surveys I had conducted in the previous project with Dan Smith. When I carried out the case studies, however, I preferred qualitative methods, as I needed to reach a deeper understanding of the conflict and its context. As a general rule, I think there is far too little collaboration between quantitatively and qualitatively oriented researchers.

Another issue is the lack of awareness about limitations in one’s own method, on both sides of the aisle. With regard to how I had selected my case countries, it was reassuring to know that I had done this systematically. This gave me a good basis for the qualitative work, lending strength to the findings and the reasoning around the conclusions as well. The qualitative methodology also gave me a lot of important material based on interviews and key documents that were useful. And with the quantitative data as a foundation, I was on solid ground when comparing the countries based on their level of economic development. This was very useful. I don’t think there needs to be any contention between the use of qualitative and quantitative methods. It would be good to have more dialogue and reach a better understanding of the limitations of both.

The Importance of Fieldwork

You have a good deal of fieldwork experience. How has that impacted your research?

Yes, you are right that I have done a lot of fieldwork. In addition to the fieldwork already mentioned, I have had projects with fieldwork in Colombia, Nepal and Sri Lanka. I have also carried out several projects focusing on local models of peacebuilding in Haiti. In the doctoral study, it was incredibly useful to bring out the comparative perspective. I saw, for example, that the land issue – the struggle for access to land and natural resources – was extremely important as a cause of conflict, especially in the smaller conflicts. I found this consistently and clearly. However, I think this is a conclusion that it would have been difficult to reach without having done fieldwork.

Wenche on a project trip to a Nepalese village, 2016. Photo: Private archives

Since then, I have become very interested in peace processes, and in disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) processes, particularly in the gender perspective of these. The interest in peace processes started while I was working with Dan Smith, and I was asked to carry out an evaluation of Norway’s role in the peace process in Guatemala. This brought me very close to the Norwegian actors who were involved there, for example State Secretary Jan Egeland, a former PRIOite who was also the head of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Gunnar Stålsett, who was there as a representative of the Lutheran World Federation (LWF), and Petter Skauen from Norwegian Church Aid (NCA). The evaluation work not only gave me a close-up view of a peace process, it also led me to think more about how peace is achieved.

Recently, I have focused more on the post-conflict phase, and on disarmament, demobilization and reintegration processes in particular. There are several important issues that I am interested in, particularly the gender perspective and the role of minors in conflict. This focus has developed mainly as a result of questions that have come up during fieldwork.

The data I have collected and other findings during fieldwork have given rise to several new research projects on these topics. One example is the WOMENsPEACE project, where we studied women’s participation in conflict and peace processes in Nepal and Myanmar. During interviews with ex-combatants in Nepal in 2016, I realized that several of them had joined the Maoist Army as minors, and then I also became interested in doing more research on what had happened to these minors after the DDR process, and to investigate this through a gender perspective. We must not forget that the minors are also females and males.

The Utility of the UN in its Various Roles

You have attended several major multilateral conferences, and you have also studied the UN contribution to peace processes. What are your thoughts on the conferences you have participated in, as well as the role of the UN in peace processes? What are the opportunities and what are the challenges?

The first UN conferences I attended were as a representative of the North/South Coalition. I attended the UN conference for Least Developed Countries in Paris in 1990, the United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development in 1992, and the Social Summit in Copenhagen in 1995. These conferences were highly relevant to North/South issues, which is why I took part in them. I learned a lot about rows between countries at such conferences, since every country has its fads or pet objectives that it wants to gain acceptance for. It takes an enormous effort to reach an agreement on a text, and the process can be tedious. The result is often the least common denominator. Still, these conferences are important. I personally had a mixed experience though. In part, it was nice to see that joint efforts were made, and the countries were able to agree on a text. On the other hand, the text would inevitably be watered down along the way, because of the difficulty of reaching an agreement when everyone held on to their pet objectives.

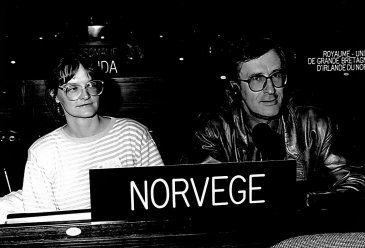

Wenche and Øystein Tveter as members of the official Norwegian delegation to the UN Conference on the Least Developed Countries, Paris, 1990. Photo: Private

Since then, I have seen more of the UN in other roles and contexts. I found that the UN played an important role as a mediator in the last stages of the peace process in Guatemala, from 1994 to 1996. In that case, Norwegian actors were engaged in the early phase of the peace process. However, it came to a point in 1994 when the process reached a stalemate and it became important to have a mediator with more leverage, and so the UN was brought in. This was when Jean Arnault was appointed as a mediator in the peace process. He was a very skilled person who, together with the others involved, not least the conflicting parties themselves, managed to bring about a final peace agreement in 1996.

I have found that successful peace processes are marked by close interaction between various actors who have been involved for a long time, who know the conflict and the parties well, and who have gained their trust. Trust is more important than anything else. The long-term actors might also be from NGOs, or civil society. They certainly don’t have to be people from political circles. They are vitally important in the first, most difficult phase, when the process is vulnerable, and trust is gradually built. This creates a foundation for the UN to play a role in later stages.

I would say that a successful peace process is characterized by a good division of roles and wise interactions between the various actors involved in the facilitation and mediation. I have less faith in peace processes where there is a lot of prestige involved, and where people from the UN are drawn in without any special relationship with the parties, or without the trust that is needed.

The UN is a large apparatus, and when it enters a process, the dynamics are immediately changed. However, at some point, this is often necessary, not least when a peace agreement has been signed, and in the demobilization phase, when there is a need for security and monitoring, and when it’s time to disarm non-state actors and organize the surrender of weapons. At this stage, the role of UN agencies can be critical.

I would say that a successful peace process is characterized by a good division of roles and wise interactions between the various actors involved in the facilitation and mediation. I have less faith in peace processes where there is a lot of prestige involved, and where people from the UN are drawn in without any special relationship with the parties, or without the trust that is needed. A good interaction between different actors is important.

In Colombia, Norway played an important role in the peace process. The UN was involved in a major way only at a late stage. UN agencies were strongly involved in the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration process. In general, I think many peace processes could benefit from the UN staying longer into the post-conflict period, when the implementation process begins. This is the most vulnerable phase of a peace process, the point when armed groups have given up their only leverage for the implementation of their demands: the capacity to use their weapons. At this point, it is important that an independent party is present to monitor the implementation of the peace agreement and ensure compliance by all the parties involved, including the government authorities and the security forces. Not least for the sake of civil society, the UN is very important at the crucial final stages of a peace process.

Thank you for sharing your important insights, Wenche.