Uganda has signed a pipeline deal with Tanzania and Total to transport crude oil from Uganda’s Albertine region to Tanzania’s Tanga port for refining, but the secrecy that surrounds this $3.5 billion project attracts questions around its viable benefit to the citizenry. For Uganda, this oil presents huge opportunities and significant risks.

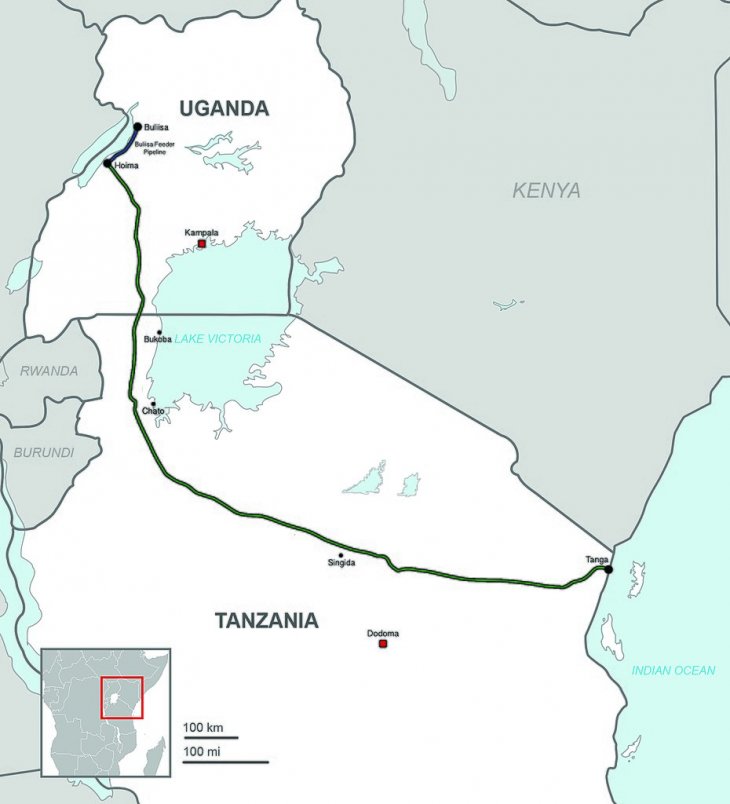

Proposed Uganda pipeline. Wikimedia Commons

At all London Tube stations, there is a consistent reminder to “mind the gap between the train and the platform.” This is to always alert travelers about the risk of not taking the necessary precautions when entering and leaving the train wagons. It is precisely to avoid any accident that may arise when they miss a step and get trapped in the gap between the train and the platform.

I apply this analogy to Uganda’s oil resource programing and the highly theorized ‘resource curse’ or ‘paradox of plenty’ or the ‘poverty paradox’ to insist on Uganda’s need to ‘mind the gap’ between her oil resource and the likely outcomes.

Decades ago, Uganda made commercial oil discoveries. Since then, the country has made more strides, through the legal and policy framework, to manage this resource.

Not so many years ago, Uganda emerged from conflict and made a transitional justice (TJ) policy to address, not only its past conflict legacies, but also the regional disparities that exist in development in all its dimensions. However, the secrecy of oil policies and laws provide a conducive environment that may manifest a consistently theorized ‘resource curse’ phenomenon with a missed opportunity to address it through the TJ policy.

The resource curse is literally a situation of abundant natural resources co-existing with less economic growth, less democracy, or worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources, as Smith and Walder reiterate in their new book “Rethinking the Resource Curse”.

At the height of this theory is poor resource governance that culminates in conflict. Oil is a dominant resource whose governance has either provided transformative outcomes for countries where it exists, or defeated the purpose of its existence and the optimistic outcomes that come with it.

Uganda’s civil society has continuously engaged different line ministries on the importance of managing the country’s resources for the benefit of all citizens, especially those that still live in abject poverty. Through comments from citizens evident in reports and documentaries like “Uganda’s Black Gold” by the Refugee Law Project, the population’s fears, challenges and hopes with its oil were examined from more than eight years ago.

These reports and documentaries indicate tension and a sense of marginalization especially by the residents of districts in the Albertine region where oil was discovered. Issues range from job creation, displacement and compensation, and environmental protection. These are also issues of mistrust, challenges of ownership, potential for conflict, environmental conflict, and local beneficiaries, with emphasis on open discussions and agreements between the citizenry and their government as a remedy.

In the Foreword of Uganda’s National TJ Policy, the Government of Uganda’s commitment to peace and justice is reaffirmed with justice promoted as a necessary precursor to sustainable development, attributed to the National Development Plan which is a ‘peaceful and stable Uganda’.

The Albertine region is among areas that have been mostly affected by past armed struggle, which has slowed its growth, destroyed and disrupted its infrastructural development. Addressing these wrongs would mean more attention to the needs of the people in this area through policy to benefit from the proceeds of a resource (oil) discovered in their region. Guided by the country’s transitional justice policy, it is incumbent upon the legal regime to ensure that the resources are well distributed and ensure regional development as an approach to preventing future conflicts.

In the spirit of righting wrongs, government must accommodate democratic nationwide conversations on how these resources can be governed. Restricting these discussions to a few ‘experts’ and ‘political players’ is a mistake that will take decades to rectify. This is because the legal and policy frameworks on natural resources governance do not only affect political players, but also people at the grassroots affected by what Abiodun Alao calls the ‘overarching national interest’ through eviction from their land without due compensation, and a loss of habitat, including the flora and fauna, their source of livelihood. Transparency and accountability in the whole process from discovery, exploration to sharing into the revenue from these resources is a prerogative that every institution or individual must hold in high regard if Uganda is to circumvent the ‘resource curse syndrome.’

Learning from the history of conflict and stagnancy in other resource-rich countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Nigeria and Angola, Uganda has the choice to make of whether to follow the path of a blessing like countries such as Botswana and Norway, or to tread the curse trajectory like countries in the former. If Uganda’s choice is the latter, minding the gap is through promoting transparency and accountability is essential.

- Dennis Jjuuko is a Doctoral Student of Global Governance and Human Security at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

- The Project: Green Curses and Violent Conflicts

Nice research indeed

This is a great piece. How I wish our policy makers can choose the path of a blessing!