Most Arab countries today are governed by more or less authoritarian regimes that nourish a patriarchal social and political order. This order marginalizes young people, and particularly women.

There are moments when it is openly challenged. We saw it across the Arab world in 2011 and afterwards.

Several art forms contributed to this open conflict, and among them were independent adult comics – a cultural phenomenon that really took off during the Arab uprisings and afterwards.

I think this is a medium that deserves more attention, because it shows how central cultural products can be to make sense of political dynamics. But this post is not about comics as revolutionary art. I am going to look at less explicit – but no less interesting – ways in which comics challenge patriarchal authoritarianism.

Why less explicit? The space for criticism in the Arab countries is narrow, and the personal cost of crossing red lines may be very high. This applies to art, too. Just think about the court case against Lebanese comics collective Samandal, or the harassment of Egyptian cartoonist Islam Gawish, to mention to examples. Enter political theorist James C. Scott and his concept of “hidden transcripts” as an “art of resistance”.

Here is Scott’s idea: When open criticism of the system is not accepted, and when those who are dominated lack the means to openly challenge the powerful, then people devise more circumspect ways of expressing their discontent and undermining power. They devise what Scott calls hidden transcripts. The hidden transcripts stand in contrast to public transcripts. For Scott, the public transcript is the “open interaction between subordinates and those who dominate.” Here, the dominated have to talk and behave as is expected of them as underlings. In contrast to this discourse of obedience, the hidden transcript is “discourse that takes place “offstage,” beyond direct observation by powerholders.” It consists of quiet non-conformism, jokes about the power-holders, gossip, poems or fairy tales and other cultural expressions that resist, ridicule and criticize the system.

Sometimes this hidden transcript finds its way into the public sphere. It is expressed in the form of allegories, allusions, codes, or metaphor. Such critique and challenges to the system are expressed in ambiguous or indirect ways and thus it is difficult for power-holders to crack down on them. I’m going to use this analytic lens on three Egyptian and Lebanese comics. Specifically, I will focus on how these comics use the feeling of alienation to express social and political criticism, and I will show how the apparently personal may be read as an expression of social solidarity with oppressed groups in society and with their rebellion against the system.

“I’m fed up” in Egypt

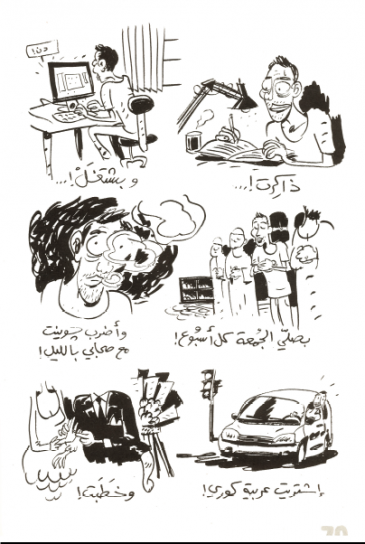

Let’s look at Muḥammad Shennawy’s little story “Zuhuqt”, or “I’m fed up.”

This story by Mohammed Shennawy (from the Egyptian comics magazine Tuk-Tuk 8 in 2012), in effect constitutes a claim to youthfulness in a hostile environment. Shennawy’s protagonist talks to the camera and says that he is fed up with his life in Cairo, with his life in general. He then presents a list of what “everybody” does, to prove that he has done all he could to have a meaningful life: studying, working, buying a Korean car, getting engaged. Funnily, he also lists “smoking joints on Friday night” right after “going to the mosque every Friday”.

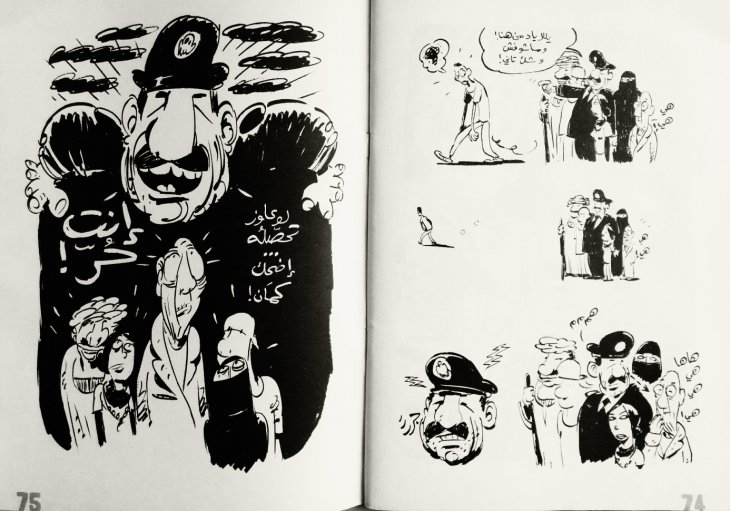

His outburst draws the attention of a police officer and several bystanders, and none of them sympathizes with him. The police officer heaps abuse on him and slaps him in the face, accusing him of being among the revolutionary rabble. The interesting thing is that what awakens the rage of the police officer and the bystanders is not the fact that he smokes a joint now and then, which is surely illegal, but the fact that he “is fed up”. He is simply not allowed to be fed up, to be tired of it all. With the group of onlookers, Shennawy foresees the emergence of an alliance of the repressive state and what came to be known as “honourable citizens, al-muwatinun al-shurafa” – people who remain loyal to the repressive state and collude in vilifying dissenters. A group such bystanders express their disgust at the protagonist and laugh him when he is mistreated.

But then the police officer, the representative of the state, turns on them afterwards: He threatens to beat up the old man who doesn’t stop sniggering. Nobody is allowed to laugh unless specifically told to do so. In the last frame,

the young man and the old man who laughed at him sit together in the silent solidarity of the oppressed.

When Shennawy published this story the military had for some time been in the process of forcing young Egyptians’ open opposition to the authoritarian, patriarchal order underground by using brute force (think of the Mohamed Mahmoud incidents in late 2011). The risks and dangers of open opposition are immense, and so criticism becomes veiled. Shennawy’s story is funny, personal and light-hearted, so it hardly incriminates him. But for those who can recognize the characters and the setting the story nevertheless radiates dislike of the authorities and solidarity with those who are oppressed by the system. The story is easily read as saying that ordinary people are oppressed by the state and that they are in it together. At the same time, it cannot easily be clamped down on by the state because it does not explicitly criticize anybody, much less encourage people to protest.

“Short breaths” in Lebanon

Veiled alienation and quiet defiance are on display in contemporary Lebanese comics, too.

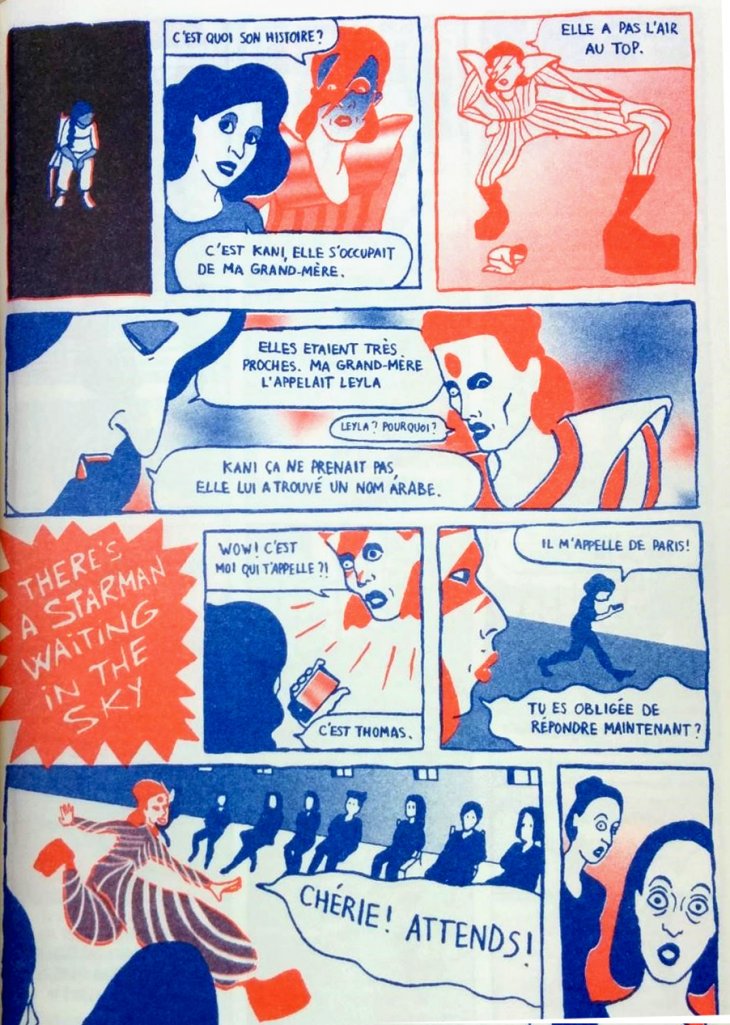

First we’ll look at Raphaelle Macaron’s Souffles courts (short breaths) from 2015, which revolves around the funeral of an old Catholic woman, gathering all her relatives in a little village in Lebanon. With humour, sarcasm and compassion Macaron depicts the dynamic in a family that is dispersed and whose members apparently have little contact with each other. For my purposes here I’ll emphasize the way she depicts the young people, all of whom reject the company of the family and the politicized funeral ritual of the Maronite priest (he uses the funeral sermon as a platform for talking about the situation of Christians in Lebanon). Instead, they seek to be alone in different ways. Here is Marya, who just wants not to be noticed, because she is tired of the attempts at imposing social control on her by older members of the family. Notice how we share her perspective on the left hand page, the stream of annoying faces, questions and comments she has to relate to. She seeks solace in the company of David Bowie, who implausibly appears on the scene, a total alien in this setting. His absurd appearance on the scene underlines the sense of not belonging. Again, it’s easy to imagine an underlying message here: “I don’t like this setup. I don’t want to be part of this social order.” And if you read the whole story you will notice there’s solidarity between the young people, the total outsider (David Bowie) and even the dead grandmother, who doesn’t have to relate to the system anymore.

Now what are the public and the hidden transcripts here? The public transcript is that young and old alike conform to the social expectations of the various communities, and that they accept that clergy use even funerals for spreading political messages. But there is also an expression of a hidden transcript: exasperation with patriarchal values and a social system where young women are constantly controlled and monitored, where intolerant attitudes flourish – and an urge to be liberated from this whole system, to run away (with David Bowie) to a less oppressive reality.

“Furr Furr Blues” in Lebanon

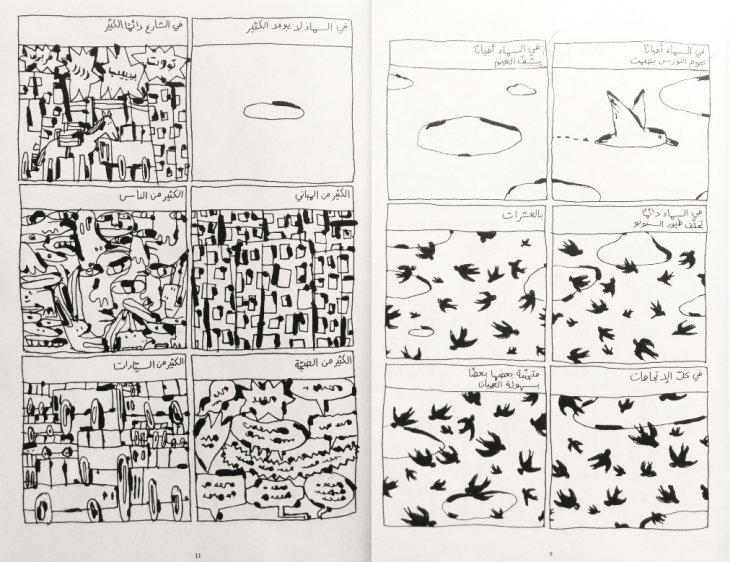

The second example is the story “Furr Furr Blues” by Mazen Kerbaj, which appeared in Samandal no. 12, 2012.

In the beginning the comic seems to highlight the contrasts of an Arab cityscape – from the quiet purring, the “furr furr” of the doves, to the hectic, loud street. The frames are tranquil and quiet at first. Then they suddenly become cluttered with faces, buildings and vehicles impossibly stacked on top of each other.

Then, in full-page panel, a woman is introduced as the narrator comments: ‘Those with beards [i.e., religious men] – here and everywhere – spend their time claiming that they don’t spend their time looking at the women who walk the streets.’ And from this moment on, the story shifts gears and becomes a blues about how sad public spaces are when women aren’t present in them. On the subsequent pages, the woman is soon squeezed out of the frames, which are filled with the eyes and mouths of men.

Towards the end, and as the sun sets, we see two women gradually losing their features and becoming empty shapes as the text reads:

There is nothing but them [men] after sunset. How sad is the sunset which conceals the sun and the women and signals the onset of sad nights in which women (…) go and make their purring noises elsewhere.

Aside from the melancholy, there are a couple of implicit messages we can read from Kerbaj’s combination of text and images in this comic. First, look again at the right-hand side of the second image. The observations of the narrator switch from a panel depicting aerial pollution (the two middle panels) to two panels which introduce men. But the exact same textual formula is retained – ‘a lot of pollution’ is followed by ‘a lot of policemen’ and ‘a lot of men with beards’, i.e., conservative religious men. The formulaic text and the juxtaposition of apparently disjointed images is a clever piece of irony: Kerbaj avoids making any explicitly disrespectful link between urban pollution on the one hand and policemen and conservative religious males on the other. However, it does not take much imaginative energy on the part of the reader to make the link for him/herself.

Notice also the contrast between the seemingly innocent text and the threatening images: ’a lot of policemen’ is just a statement of what is in the picture. However, while the text looks innocuous the images convey a sense of threat and discomfort. None of the men he draws shows the slightest hint of a smile. The policemen either look mean or angry. The religious men appear as serious and disturbed at the same time, an effect Kerbaj achieves by dislocating their facial features. The impression one gets is that the street is dominated by distorted, vaguely threatening male bodies.

In effect, Kerbaj criticizes a society where the state (the police) and religious authorities conspire to marginalize women. But Kerbaj does not say that in so many words. His critical message is easy to pick up, but it is not uttered explicitly. Instead it is implied by the rhetoric of the panels and the text/image dynamic.

Both Macaron’s and Kerbaj’s stories of an oppressive social space assumed a remarkable relevance in Beirut in late summer 2015, when the ‘You stink’ campaign took off. This is because the gender dimension of these protests was prominent – feminists and LGBTQ activists were a vocal part of the movement. In analyses that perfectly mirror Kerbaj’s comic, the feminist activists described how the political factions and the security forces resorted to an aggressive masculinization of discourse and public space when trying to repress the protests. Political leaders questioned the morality of female demonstrators by admonishing them to listen to their fathers and sectarian leaders. Authorities and security forces also ridiculed and suppressed everything that is not traditionally masculine, from homosexuality to discussion that gives room for the other. The female activists in the protests went beyond Kerbaj’s elegy by breaking with the strategy of withdrawal that Kerbaj mourns in his story: In workshops and seminars these activists confront the problem head-on by working to feminize public space and discourse. The hidden transcript is brought out into the open, in other words.

Conclusion: an art of resistance

Adult comics has often been seen as an iconoclastic art form, art that openly breaks taboos. Open challenges to power are not uncommon in the Arab adult comics of the last seven years (go to Jonathan Guyer’s excellent blog for both political and non-political comics in the Arab world). But I think that we should also pay attention to the more subtle aspects of these works, where seemingly innocuous, personal stories can just as well be read as damning criticism of the system. The three stories I have been looking at here all employ a strong sense of alienation, be it political or social or both, a sense of alienation to signal solidarity with all those who are oppressed by the system. This feeling is shared by so many young people in Arab countries, people who have no illusions about the systems they live under. In that way these comics are more than personal artistic expressions. They also contribute to building a sense of community, a community of the dominated, and to express their solidarity with it. In this way, comics really are what Scott calls: an art of resistance.

I originally presented this material at the Mahmud Kahil Award symposium at the American University of Beirut (AUB) in February 2017. Thanks to Lina Ghaibeh at AUB for giving me that opportunity!