Every generation has its own concept of the Middle Ages. Game of Thrones is a fantasy drama, but it also reflects the present, viewed through the prism of the Middle Ages.

From Middle-earth to Westeros

Many young people today picture our distant past in a way that is strongly influenced by The Lord of the Rings. There the battle is between good and evil and – except in the case of some turncoats (such as Saruman) and certain conquered lands – the battle fronts are clear. This reflected Tolkien’s own experiences, both in the trenches during World War I and as he composed his epic work in the shadow of World War II. Tolkien took inspiration from Beowulf, The Elder Edda and The Kalevala to describe a human universe that is a battle between the forces of good and evil, between freedom and tyranny, between individuality and regimentation.

All hope depends on the ruler Daenerys Targaryen. Still the most important and complex figure of the Middle Ages is the advisor – here represented by Tyrion Lannister. Photo: HBO

“I don’t believe that giants and ghouls and white walkers are lurking beyond the Wall. I believe that the only difference between us and the Wildlings is that when that Wall went up, our ancestors happened to live on the right side of it.”Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones, Season 1

A battle between such forces is still taking place today, but with the major difference that the battle fronts are mutable. Western interventions designed to liberate regions such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Libya from dictators and extremism have had the opposite effect: violence is increasing, security is being eroded, and extremists are growing ever stronger. One may do evil despite good intentions.

Accordingly, it is not surprising that Game of Thrones, the latest epic narrative to be set in an imaginary past, is a tale where heroes and villains swap roles, where good people often suffer defeat, and where “the road to Hell is paved with good intentions”, to quote Bernard of Clairvaux.

England at the centre of the universe

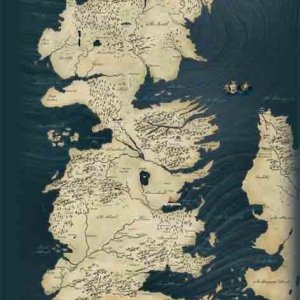

Game of Thrones centres on King’s Landing, the capital of the continent of Westeros . King’s Landing is the seat of the King of the Seven Kingdoms, who rules surrounded by his advisors and his army of knights and infantry. The city is protected by such high walls that even a hostile navy is unable to capture it. Westeros is feudal Europe, a world where tournaments represent the chivalrous face, and court intrigues represent the sleazy obverse, of the knightly universe.

The northernmost of the seven kingdoms on Westeros – known as The North – is home to Winterfell. The North is inhabited by the Northmen, a people who are tougher and more primitive, but also less corrupt, than their counterparts to the south. The dour character of the Northmen is also influenced by the presence of The Wall, which forms The North’s northern border, and which so far has held back the Wildlings and ghoulish creatures that inhabit the lands beyond.

If one looks for direct historical parallels, one soon finds striking similarities with English history, particularly the Wars of the Roses (1455–87). This is true not only of the names of the warring parties – Lancaster has become Lannister, and York has become Stark – but also of much of the action. As in the real-life Wars of the Roses, the background to the conflict in Game of Thrones is a “mad king” (Aerys Targaryen /Henry VI). Many commentators have pointed out that Cersei is based on Margaret of Anjou, who was married to Henry VI and in practice ruled in his name. Cersei rules on behalf of her sons, as did Queen Gunnhild in Norway following the death of Eric Bloodaxe.

Game of Thrones has been criticized for sexism and extreme violence. Although the series features many powerful female characters, they frequently suffer horrific attacks, particularly of a sexual nature. We know little about the most private aspects of people’s lives in the Middle Ages, but the life of a woman such as Ingeborg of Denmark, who was married to Philip II Augustus of France, and then shunned by him for 20 years until strong pressure from the Pope led to her reinstatement as queen, can scarcely have been easy. Even so, the constant rapes – including marital rapes – suffered by female characters in Game of Thrones seem far-fetched. Women were used as security to cement alliances between dynasties, and mistreating a spouse would seldom have had a good political result.

The perilous margins

The similarities with England in Game of Thrones also extend to geography, and the landscape from King’s Landing to Winterfell could be mistaken for that of England. Like London, King’s Landing lies on a river to the south-east of a land mass , and The Wall is reminiscent of Hadrian’s Wall, which was intended to keep ‘the barbarians’ out of Roman territory.

The similarities with England in Game of Thrones also extend to geography, and the landscape from King’s Landing to Winterfell could be mistaken for that of England. Like London, King’s Landing lies on a river to the south-east of a land mass , and The Wall is reminiscent of Hadrian’s Wall, which was intended to keep ‘the barbarians’ out of Roman territory.

The Wildlings are reminiscent of the Jötnar (“devourers” or “Giants”) of Old Norse mythology. Unlike Sauron and his Orcs in The Lord of the Rings, the Jötnar were not associated exclusively with evil and otherness. There are many Old Norse myths in which Jötnar and humans interact, and even have children together. Undoubtedly the Jötnar could be foolish, but they were also valuable, as they had access to wisdom and resources. Accordingly, Odin was willing to hang himself from the great world-tree in order to learn the secrets of the runes, and the gods went to desperate lengths to get hold of female Jötnar.

Many commentators have suggested that the Jötnar were a fictionalized version of the northern Sámi people, who were treated as outsiders but simultaneously highly valued as trading partners. According to the Old Norse Kings’ sagas, several Sámi women bore children fathered by Norwegian kings. In Game of Thrones, the Wildlings represent a similar people. Initially they are purely hostile, but they become at least partially integrated into the civilized world (as illustrated, among other things, by the story of Tormund Giantsbane, played by the Norwegian actor Kristofer Hivju).

To the south, we find fairytale cities with exotic peoples and wares, and a long history of civilization, accurately reflecting the role of the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages. In the east are the barbaric and nomadic Dothraki tribe: fearsome warriors who live their lives on horseback.

The real-life equivalents to the Dothraki were the Mongols. The Mongols, and nomadic tribes more generally, posed an almost constant threat to Europe in the Middle Ages – from the fall of the great empires in around 500 A.D. until the time Europeans used ships and canons to conquer the world a thousand years later. In general, Europe was the only major region in Eurasia not to be invaded by nomadic tribes. Exceptions were the migrations of the Germanic tribes following the fall of the Roman empire, and of the Vikings and Magyars in the 9th and 10th centuries, but the significance of these events is minimal compared with the conquests made by the Mongols in Central Asia and China, and by the Turkic tribes in the Middle East.

The advisor

At one point, Queen Daenerys Targaryen explains why she prefers her advisor, Tyrion Lannister, who is a dwarf, to heroes such as Jon Snow, Jorah Mormont and Daario Naharis: “Heroes do stupid things and they die. They all try to outdo each other. Who can do the stupidest, bravest thing?” Heroes burn brightly, but are quickly extinguished. Tyrion has nine lives and is also the human face of Game of Thrones: the man who does not live up to the heroic ideal, but who also cannot abide the evil ways of his sister Cersei.

Tyrion embodies the most important and complex figure of the Middle Ages: the advisor. Like all advisors, Tyrion is walking a tightrope: he does not make decisions himself, but is quickly blamed if things goes wrong. Tyrion is primarily an expert judge of human nature, and as such – unlike a hero – gets to live a long life. He explains this in his own words to Daenerys: “You need to take your enemy’s side, if you’re going to see things the way they do! And you need to see things the way they do if you’re going to anticipate their actions, respond effectively and conquer them!”

“Keep your friends close but your enemies closer,” is the best recipe for survival in a world where everyone is out for themselves, but also enmeshed in complex networks over which they have no oversight. This even applies to the ruler sitting on the Iron Throne, for he or she cannot proceed at his or her discretion. Nor can he or she act on the basis of noble intent – since, as shown by the Starks’ bitter experience, you can’t depend on others to do likewise. Even behaving like a Machiavellian duke is no good, because you may be on the receiving end of the same behaviour, as the brilliant politician Tywin Lannister becomes painfully aware.

The ideal ruler

Daenerys Targaryen is the great conqueror in Game of Thrones, and all hope depends on her. We still don’t know her eventual fate, but her background and career so far are extremely interesting. Her father was the “Mad King”. He was killed and his descendants virtually wiped out. Accordingly, Daenerys begins from the lowest point possible – her royal blood excepted. Her royal blood brings her marriage to a Dothraki warlord, although this brings her no power – something of which her brother becomes very solid evidence.

Daenerys’s great trump cards are her dragons. Dragons are important mythological beasts, but in Western culture they are often associated with the devil, for example in the legends about the dragons slain by St. Michael and St. George. At best, dragons represent forces of nature that must be eradicated if one is to found a civilization (according to the historian Jacques Le Goff, dragon-killing legends were based on a mixture of heathen folklore and traditional Christian ideas about the devil). But the dragons under Daenerys’s control are like her children, and as such are more like Chinese dragons, whose role was to protect the emperor. In addition, their military impact is strikingly similar to that of a bomber aircraft.

But even dragons can die, and in the long run it is Daenerys’s qualities as a ruler that are decisive for her success. At Slaver’s Bay, she frees slaves and wins their trust. But the slave owners form secret societies and Daenerys barely escapes from them with her life. In the past, many historians believed that King Sverre of Norway had brought about a social revolution when he said, “Kill a landed man and you will become a landed man, kill a royal bodyguard and you will become a royal bodyguard.” In the case of Sverre, the social structure stayed the same; it was merely the personnel who were replaced. Daenerys’s experiment shows how difficult it is to create an idealistic, equal society, and reminds us of historical examples, such as the French and Russian Revolutions, where attempts to do so misfired.

Both Daenerys and Jon Snow approach the image of an ideal ruler, but they also have steep learning curves. Both have to fight against exaggerated idealism: Daenerys at Slaver’s Bay, and Jon at Castle Black. Love is a force that binds the people closest to Daenerys to her, but for her to show too much love – or too much love for just one individual – is a fatal weakness, because a ruler must always maintain a balance between different factions. Intervention may be the right course of action, as when she helps people in The North, but in other cases it is misdirected.

“You must be merciless if you want to take the throne. You must make people fear you,” says Tyrion. But at the same time, power is fragile if it is founded only on fear, as the story of Cersei shows. In the end, what saves Daenerys is that no one can be completely certain where they stand with her. In this way, Deanerys – surprisingly enough – may remind us of a political leader who has made unpredictability into a brand and demonstrated the fragility of the foundations of our democratic institutions and political ground rules: Donald Trump. But the important difference is that where Trump has chosen to ignore such institutions, Daenerys lives in a society where they do not exist.

- This text was published in Norwegian in Klassekampen 13 August 2018: ‘Fra Midgard til Westeros’. Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext