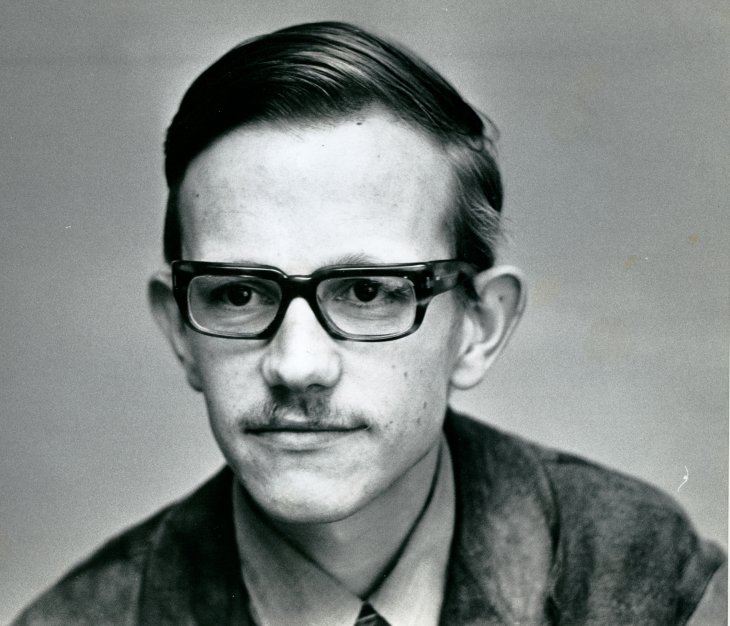

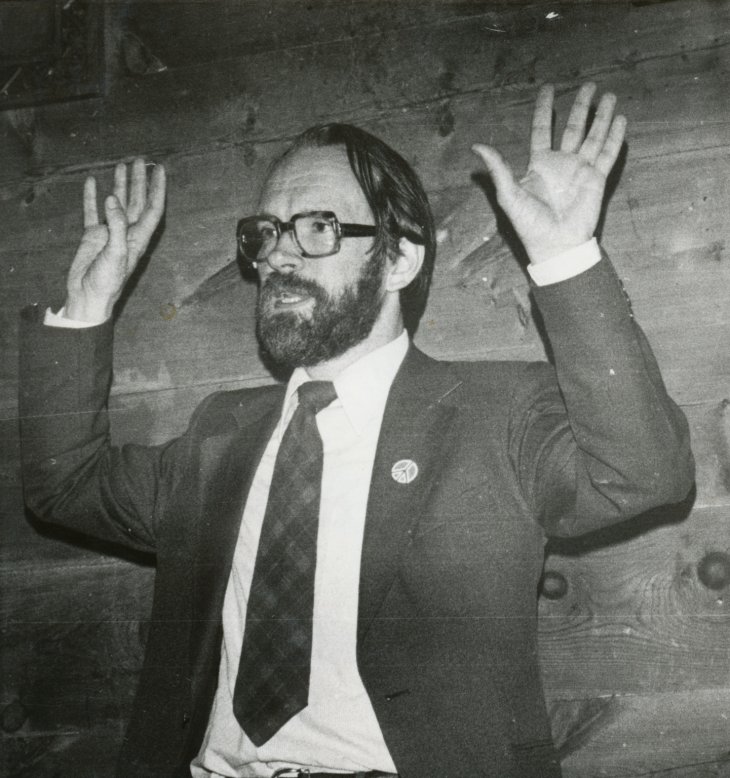

Nils Petter Gleditsch. Photo: PRIO

Nils Petter Gleditsch, interviewed by Hilde Henriksen Waage

If you read my older publications, you will find very little about democracy, but a lot about equality, justice, and peace. The idea of a liberal peace, built on ties through international trade, became a major theme in peace research at the end of the 1990s. I was actually skeptical in the beginning, even after I had embraced the idea of a democratic peace. But I have come to realize that economic cooperation and development are important drivers of peace. … Thinking of all the crimes committed in the name of socialism, I find it difficult today to call myself a socialist. However, I have no problem calling myself a social democrat. … I have actually tried to launch a new formula for stable peace, ‘the social democratic peace’, combining democracy, a strong state, economic development, international political and economic cooperation, and a policy of non-discrimination of minorities. I think this makes a lot of sense as a policy, but I must admit that as a slogan it has fallen flat.

The above programmatic statement comes from my long-standing supervisor and colleague at PRIO, Nils Petter Gleditsch. In connection with PRIO’s 60th anniversary, I was asked to interview him.

On my very first visit to PRIO in November 1983, I attended a meeting for students who had applied for scholarships. The then head of the institute, Asbjørn Eide, told me that I – meaning my historical research – was of ‘no interest’ to the institute. PRIO, Eide assured me, would not be focusing on historical studies in the future. As I was heading out of the building, Nils Petter approached me:

‘Don’t leave – come here, I would like to talk to you’, said the famous (to me, at least) Nils Petter out there in the corridor. Thirty-five years later, we were sitting in my office at PRIO, conducting this interview. We both still work at PRIO.

Nils Petter Gleditsch: In other words, you are not exactly a neutral observer?

Hilde Henriksen Waage: Well, I would like the readers to know that we know each other very well. I have gone through the whole gamut of roles at PRIO – from student to director – and you have been here all the time, correcting my various research drafts in handwriting with a green felt-tip pen.

So, let’s start. How was your childhood – your upbringing, the environment you were born into?

In a sense, I was born into the labor movement. Both of my parents were active in the socialist organization Mot Dag. Both were active in the solidarity movement for the Spanish Republic during the Civil War at the end of the 1930s. My mother spent long periods in Spain, helping to channel aid from Scandinavia to a hospital in Alcoy as well as an orphanage in Oliva. At the orphanage she became attached to a young girl, Christobalina, whom my parents eventually adopted.

Nils Petter Gleditsch arrived in Norway for the first time on the British ship Andes on 30 May 1945, safe between his parents and accompanied by his aunt. Photo: Unknown / NTB Scanpix

This background from the labor movement shaped my political views in my youth. When I was sixteen years old, I jointed the Socialist High School Association (Sosialistisk Gymnasiastlag), affiliated with the youth section of the Norwegian Labor Party. I have been a member of that party since then, except for some years in the 1960s when I was a member of the break-away Socialist People’s Party (SF).

A second aspect of my background is that both my mother and father came from upper-middle class families with names going back to resourceful immigrants. Carl August von Gleditsch was a German officer who served with the Danish-Norwegian army and was stationed in Norway from 1790. My mother was a Haslund, the name originating with two brothers who immigrated from Denmark in the middle of the 1700s.

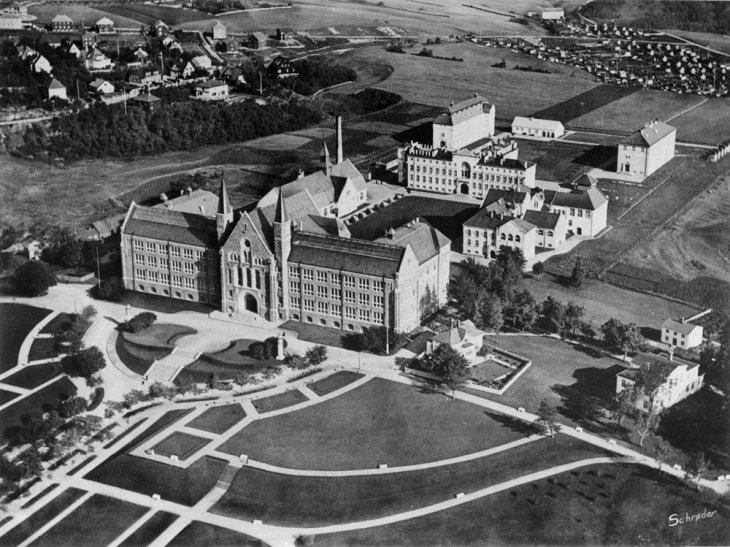

A third aspect of my background is science. My father was a civil engineer, educated at Norges Tekniske Høyskole (NTH) in Trondheim, today a part of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). His oldest sister, Ellen Gleditsch, was Professor of Chemistry and Norway’s second ever female professor.

My father, who probably could have pursued an academic career, left it when he became politically active. However, he returned to his old professional background when he became director of the Norwegian Geographical Survey after the Second World War. Both he and other family members took it for granted that I was going to study science. These are background factors that have shaped my life.

The prestigious Norwegian technical college (NTH) in 1933, today NTNU in Trondheim. Photo: Alf Schrøder / Sverresborg Trøndelag folkemuseum PD

You once told me that your godfather was none less than the first UN Secretary- General, Trygve Lie. Why did you need a godfather? The labor movement, in which your parents were solidly planted, was usually critical of the church and often no friends of Christianity?

You’re right that the labor movement, and its left wing in particular, had a non-religious profile. For example, the famous Norwegian author, Arnulf Øverland, also a member of Mot Dag, gave a much-publicized lecture in 1933 called ‘Christianity – the Tenth Plague’. However, when I was born, it was not unusual – even for the non-religious – to baptize their children and then leave it up to them to leave the church later, if they wanted to. Indeed, at the age of 15, this is precisely what I did, in one of my first political decisions.

But how did I become a member of the Norwegian church in the first place? Well, my parents worked for the Norwegian government in exile in England during World War II, and my mother worked for the then Norwegian Foreign Minister Trygve Lie. When Lie was told that my mother was pregnant and that her due date was close to his own birthday, he insisted that he should be my godfather. Lie was known for having strong persuasive abilities. Every Christmas after the war, ‘uncle Trygve’ sent me fifty kroner. I never told him, however, that one of the last times I used the money to buy a share in the left-oriented journal Orientering, which was in opposition to the foreign policies of the Norwegian Labor Party, probably not entirely to Trygve Lie’s liking.

Trygve Lie, 1938. Photo: Atelier Benkow / CC BY-SA / Oslo Museum

How come your parents ended up in England during the war?

After the German invasion of Norway in April 1940, my uncle Fredrik Haslund was asked to take charge of the evacuation of Norway’s gold reserves. He asked my parents, among others, to assist him, and they helped to bring the gold to Tromsø, and later to England. My father, who had studied in France, was recruited as an interpreter for the French forces fighting the Germans in the Narvik. As a result, he missed the last boat to England and had to travel around the globe – the other way! – to get to England. He walked across the border to Finland, then went via Sweden through Russia and Japan. He was denied transit through the United States, and had to travel through Canada before finally reaching England. There he worked for the security service, and also on the preparation of maps of Norway for the eventuality of a ground invasion.

Fredrik Haslund in New York in the 1940s. Photo: Unknown / Arbeiderbevegelsens arkiv og bibliotek

So, you were born into an active, socialist/social-democratic upper middle-class family? But there must have been many conservatives in your environment?

I cannot remember that I interacted a lot with conservatives … although some relatives and some of my classmates’ parents in the part of Oslo where I grew up must have been conservatives. But this was not something we talked about very much.

You went to high school at the prestigious ‘Katta’ (Oslo Katedralskole)?

I was just 13 when I when to high school, after starting primary school one year early. My parents were ambitious on my behalf, and their ambitions included expectations for a higher academic education, preferably in science. I was playing with the idea of studying chemistry, most likely inspired by my aunt, the professor of chemistry. But my interests quickly went in a different direction – social sciences.

So, you started to study at the University of Oslo?

Yes, I started up with some preliminary courses, including a couple in mathematics but, frankly, I was fed up with studying, and I got incredibly bad marks. I went to England with very vague plans about what to do there.

I don’t believe it! So, you did what is so popular these days – you took a gap year?

You can call it that, if you like. During my high school years, I had become a member of a pacifist organization, Folkereisning mot krig (FMK) the Norwegian section of War Resisters’ International. In many ways, I think that I was more of a pacifist than a socialist.

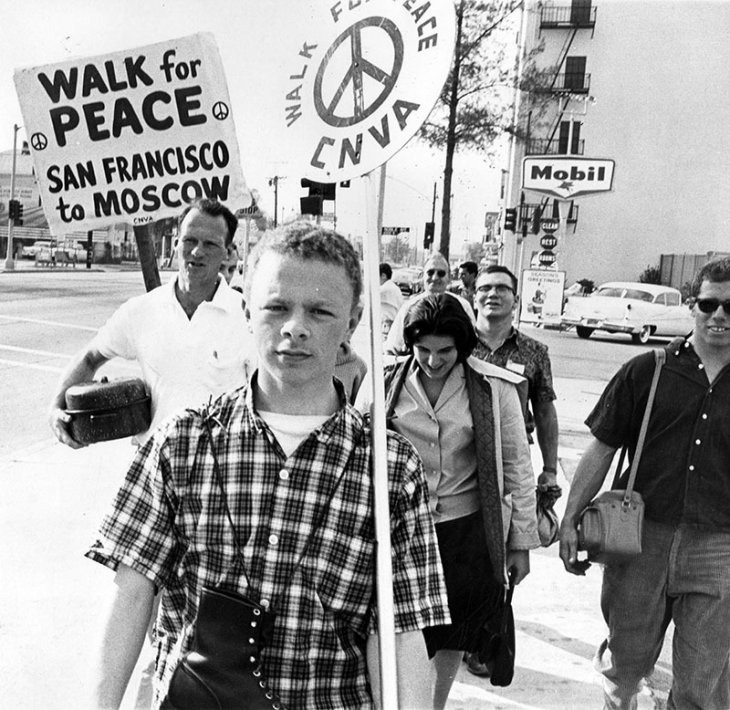

In the spring of 1961, FMK asked me to be the Norwegian participant in a peace march from San Francisco to Moscow, organized by a US peace organization called Committee for Nonviolent Action. I joined the march in London, and we set out for Moscow. We were blocked twice from entering France, walked through Belgium and West Germany, entered East Germany, and arrived in East Berlin precisely when the construction of the Berlin Wall began. The East German authorities were not interested in having us there during at such a time of unrest, so we were sent back to West Germany. We started off again at the Polish border, from which point we walked to Moscow.[1]

The 1960–61 peace march to Moscow in Sherman Oaks, California in December 1960. On the left, Scott Herrick, one of those who walked all the way to Moscow. Photo: George Brich / Public Domain/ Valley Times, LAPL

[We] arrived in East Berlin precisely when the construction of the Berlin Wall began. The East German authorities were not interested in having us there during at such a time of unrest, so we were sent back to West Germany. We started off again at the Polish border, from which point we walked to Moscow.

I have asked myself several times: why was a US pacifist organization allowed to walk through Eastern Europe with a pacifist message? It may have been due in part to the fact that the group had walked for six months clear across the United States and in this way established some sort of credibility for not being a one-sided anti-Soviet initiative. Also, the Soviet Union seems to have adopted what I call the Lyndon B Johnson thesis: ‘Better inside the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in’. The Soviets probably reckoned that they could control us.

What happened in East Germany?

We were scheduled to arrive in Berlin on 13 August 1961, which was when the East German government started to build the Berlin Wall. The authorities had found a way to delay us so that we would arrive in Berlin a bit later than originally scheduled. They fabricated an excuse that took us on a detour around the city of Berlin. Allegedly, we had to enter the capital of ‘the workers’ and peasants’ state’ first, before we entered ‘revanchist’ West Berlin.

When we arrived at the border between East Germany and East Berlin, our East German hosts told us that there were some disturbances in Berlin, so we could not go there. They had a bus, they said, that would take us to the Polish border.

So, you were sent to Poland by bus?

No, we refused. We insisted that we still intended to go to Berlin and to get there by walking, not by bus. Our East German so-called supporters carried us onto the bus, which took us to Helmstedt on the West German border, and then we were dumped there. We made it to West Berlin on an ordinary transit visa and waited for a few days, before a bus took us to Poland. From there, we walked to Moscow.

Was it in connection with this march that you met Johan Galtung? Did he participate as well?

Johan Galtung was then the chair of FMK, which had sponsored my participation. There were costs for such things as food and transportation etc, even though we generally slept on the floor in schools and assembly halls. When I returned home, FMK organized a public meeting, where I and other participants talked about the march to Moscow. This meeting was led by Johan Galtung, and it was there that I got to know him.

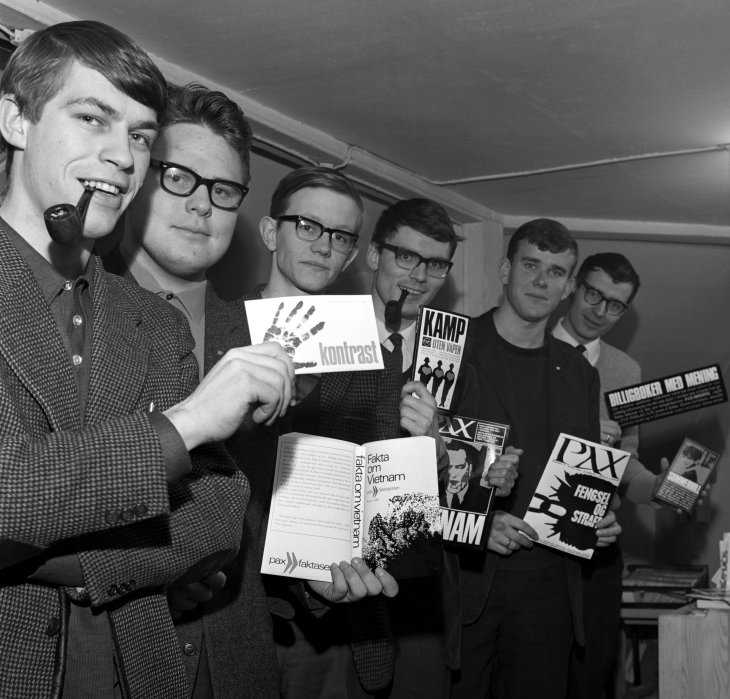

At the same time, I met Tor Bjerkmann, another man of a great entrepreneurial spirit. He wanted to establish a new journal for FMK called Pax. From 1962, Johan was the editor, at least nominally. Tor was the assistant editor, and I was on the editorial committee and later became editor. Tor’s ambitions grew. He wanted to start a publishing house, and in 1964 the first books from Pax publishing house saw daylight, with the three of us still involved in various ways.

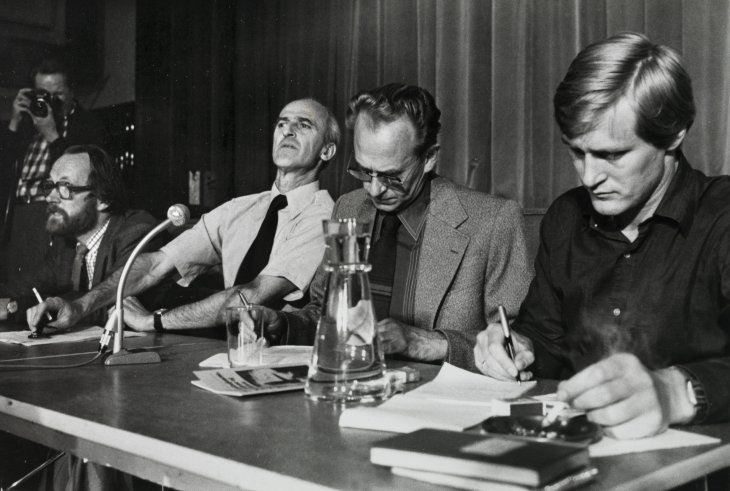

Hans Fredrik Dahl; Tore Linné Eriksen; Nils Petter Gleditsch; Kjell Rosland; Theo Koritzinsky; and Tor Bjerkmann at Pax publishing house in 1966. Photo: Aage Storløkken / NTB Scanpix

But when did you start your studies, and when and how did you come to PRIO?

In 1959, Johan Galtung established PRIO as a section of the Institute for Social Research (ISF). Initially, not many people were attached to PRIO full time. Basically, it was Johan Galtung, his wife at the time Ingrid Eide, and Mari Holmboe Ruge. After years of lobbying, public funding was secured from 1964. Johan hired two new research assistants, and I was one of them. By then, I had begun to study sociology at the University of Oslo.

So, your research career started as Johan Galtung’s research assistant before you had completed any of your studies?

Yes, and after a while, I embarked on a degree in sociology. After some discussion back and forth with Johan, who had many ongoing projects, we settled for a project on international interaction, and international aviation specifically. We coded all international flights, using a thick book ABC World Airways Guide, which contained all international flight schedules.

What do you mean by coding?

We recorded which countries were connected through international flights. An inspiration for the project was Galtung’s observation that if, for instance, you travel from one country in Latin America to another, it is often easier to travel via the United States. This is an example of what Galtung called the feudal structure of interaction; you go from the periphery to the top of the hierarchy, and then back to the periphery. If you had to go from the capital of Colombia to the capital of Venezuela, it might be easier to fly via Miami than to find a direct flight.

And this is what your thesis degree was about?

Yes, among other things. Some of my left-wing friends thought the choice of topic was weird. They wondered why I didn’t rather write about imperialism or the Vietnam War. But I comforted myself with the knowledge that a leading left-wing socialist politician, Berge Furre, a friend of mine from our days in student politics, had written a history thesis on the Norwegian dairy cooperatives. If Berge could write about agricultural cooperatives, then I could write about airline schedules!

Berge Furre in 1981. Photo: Unknown / CC BY-NC-SA / Kraftmuseet – Norsk vasskraft- og industristadmuseum

Why did you choose sociology?

For me, sociology was the natural choice. This was partly because Johan Galtung was a sociologist, but also because sociology at that time seemed more progressive than political science. In Norway, sociology had started to use quantitative data and statistical methods. Political science was more traditional, a mixture of law, history and political theory. This changed later, and I eventually ‘converted’ to political science. But in the middle of the 1960s, sociology was, for me, the obvious choice.

So, with Johan Galtung as my supervisor and mentor and, after a year at the University of Michigan, I completed my sociology degree at the University of Oslo in 1968. By now, Johan had launched an international career and was engaged in intensive scholarly globetrotting. But he was full of ideas and a very generous mentor for young social scientists.

These also included aspiring peace researchers in the other Nordic countries, like Peter Wallensteen, who later became the Dag Hammarskjöld Professor of Peace and Conflict Research at the Uppsala University and who established the Department of Peace and Conflict Research there. And Håkan Wiberg, who came to play an important role within Swedish as well as Danish peace research. Both had Johan Galtung as their main mentor.

To summarize, we have now reached the end of the 1960s. PRIO has existed for ten years, but it is still a small institute?

In 1966, PRIO became a fully independent institute. We had grown because several researchers had received funding from the Council for Conflict and Peace and the Research Council for Science and the Humanities (Norges Almenvitenskapelige Forskningsråd). These included – in alphabetical order! – Egil Fossum, Ottar Hellevik, Helge Hveem, Tord Høivik, and Per Olav Reinton. Others, like Asbjørn Eide, participated in research projects at PRIO, but held positions at the University of Oslo.

The 1960s may be characterized as a period of calm before the storm. In the 1970s, the political radicalism of PRIO researchers – with you in the vanguard – was thrust into the limelight.

Before we move into the turbulent 1970s, I would like to underline two important things: Firstly, in 1969, the University of Oslo had responded to numerous calls and established a professorship in peace and conflict studies. Johan Galtung was appointed to the position. He still took part in research activities at PRIO, but stepped down as director. To fill his shoes, PRIO established an arrangement whereby the institute would be headed by an elected leader on a rotating basis. First came Asbjørn Eide in 1970, then Helge Hveem in 1971, and then me in 1972. This strengthened PRIO’s independence, as we had to stand on our own feet, and not only live in the shadow of Galtung’s fame.

In addition, the 1968 student revolt had a great impact on all of us, not only in terms of politics in general, but also by affecting attitudes to peace research. Suddenly, it drew criticism for being ‘bourgeois’. In its analyses of conflict, peace research dealt with the oppressors and the oppressed on a symmetrical basis instead of clearly identifying itself with the oppressed. At the same time, peace research was more concerned with the East-West conflict and seemed to ignore the North-South conflict. In response to such criticism, Johan Galtung started to re-orient his research.

PRIO established an arrangement whereby the institute would be headed by an elected leader on a rotating basis. First came Asbjørn Eide in 1970, then Helge Hveem in 1971, and then me in 1972. This strengthened PRIO’s independence, as we had to stand on our own feet, and not only live in the shadow of [Johan] Galtung’s fame.

First, he introduced the term ‘structural violence’. He still defined peace as the absence of violence, but now focused on different forms of violence. One form of violence is ‘direct violence’, as – for instance – if I hit you or if a country attacks another. But then there is also ‘structural violence’, which leads to people dying because they lack resources, even though there are sufficient resources available globally. In other words, the violence is caused by the social structure. If people die because there is an uneven distribution of food or because the political system fails, then it is structural violence. Johan Galtung presented this idea in an article ‘Violence, Peace and Peace Research’ in Journal of Peace Research in 1969. This remains one of his most widely cited articles.

Two years later, he published wrote his most-cited article ever, ‘A Structural Theory of Imperialism’, also in Journal of Peace Research. This re-orientation also influenced the research program at PRIO. Initially, it opened up new and exciting areas for peace research. But it also led PRIO into several projects with a rather peripheral connection to peace research, and the field seemed to lose some of its identity.

We had a project, for instance, where the theory of imperialism was used on Norwegian regional policy. This somewhat wide approach was later narrowed down, even though PRIO might still endorse projects with a rather loose connection to peace research.

We have now been through two major themes: (1) your childhood, family background and youth; and (2) when, how and why you came to PRIO and your relationship to PRIO’s founder Johan Galtung. Now we have come to a third wide-ranging theme: (3) the political radicalization in the 1970s, and what I have named your ‘historical-critical period’, for want of a more precise term.

When I came to PRIO in 1984, you were (in)famous – a public figure in Norway. For years, newspapers, radio and television had been covering your various research projects, along with the media storm that they stirred, and finally the 1981 trial in which you were convicted of a violation of national security. Even I – with my background from the Salvation Army and other evangelical environments – knew who Nils Petter Gleditsch was, long before I dreamt of setting foot in PRIO. Moreover, PRIO was regarded as a leftist institute inhabited by radical hippies. Two – partly inter-linked – sub-themes need to be addressed here: (1) the internal governing structure at PRIO; and (2) the fight against secrecy, including the content of the secrecy – to what extent Norway was a part of US nuclear strategy.

So, let us start with the governing structure at PRIO. In a so-called ‘flat’ structure, there was an institute leader, elected on a rotating basis from among PRIO’s permanent research staff. There was the staff meeting, which constituted the highest decision-making body, and a secretary who had a top salary – and then, eventually increasing unrest and opposition toward a system that all of you had participated in creating. What was all this about, and why did it cause so much trouble?

When Johan Galtung left PRIO in order to become professor of conflict and peace research at the University of Oslo, there was no obvious candidate to inherit his mantle. So, Asbjørn Eide, the oldest of us, became the director in 1970. However, strong egalitarian currents were emerging, and they led us to decide that the director should be elected among the research staff for one year at a time.

We even changed the Norwegian title from direktør (director) to instituttbestyrer (institute leader), although we still used the form executive director in English. Helge Hveem became the head of PRIO in 1971, I myself in 1972, Kjell Skjelsbæk in 1973–74, Ole Kristian Holthe in 1975–76, and then I again in 1977–78. It continued like this until 1986, when Sverre Lodgaard returned from a long leave of absence at SIPRI in Stockholm and became director for two three-year terms.

Staff meetings were not unusual at the time. This practice was common in many research institutes. Johan had used such meetings to inform the staff about his whereabouts and other happenings and to ask the staff for advice. But after a while, a desire to give the staff meeting more formal power emerged.

Consequently, PRIO’s statutes were changed, making the staff meeting the highest decision-making body, relegating PRIO’s board to a more controlling and advisory function – almost reducing it to a subordinate body. In reality, though, the board had only in a formal sense been above Johan Galtung.

Then, in 1971, the question about salaries was raised. This issue came up because there was a difference between the salaries paid to PRIO staff members by the Research Council for Science and the Humanities and the Council for Conflict and Peace Research. Should not this disparity be harmonized?

These employees had the same positions and did the same work at PRIO. And then someone, I cannot remember who, raised the broader question of equality: should not all salaries at PRIO be harmonized? In the 1970s, this idea was not far-fetched, and it gained ground. However, it was not obvious how to reorganize the salary structure.

From left: Asbjørn Eide, Per Olav Reinton, Kjell Skjelsbæk, Marek Thee (behind, standing), Nils Petter Gleditsch, Helge Hveem, Erik Ivås, Modgunn Heilemann, Unny Sommerfelt, Susan Høivik, Fumiko Nishimura, and Johan Galtung. The magazine Aktuell published this photo in 1973, with the caption: ‘All employees at PRIO happily donate seven percent of their salary to the pot. The sum is used to equalize pay’. Photo: Sverre A. Børretzen / NTB Scanpix

The result of our internal discussion was not that everyone got the same salary. Instead, a common 17-step ladder was established, where education played a role in determining where you started out on the ladder, while advancement was based uniquely on seniority. With higher education, you would start out somewhere in the middle of the ladder. If you were a secretary, with less education, your starting position would be lower down on the ladder.

However, because seniority was the only way up the ladder; a secretary who chose to stay for many years at PRIO would reach the top and receive a higher salary than a researcher with low seniority. The system was financed by an internal taxation mechanism, which harmonized the salaries fixed by external funders by transferring parts of salaries from some of the staff to others. This system was accepted by everyone. It says a lot about its robustness that it survived for 15 years.

However, despite much egalitarian rhetoric, no other academic institution followed PRIO’s example. In the 1980s, support for egalitarian principles waned and personal ambitions grew among the researchers. Several withdrew their commitment to the egalitarian salary system and decision-making procedures. This led to unpleasant internal strife. So, the system was abolished in 1986, as a precondition for Sverre Lodgaard to return to PRIO and take up the position of director. He demanded to come to a cleared table.

I came to PRIO in 1984, and this coincided with the period when all of these egalitarian arrangements were abolished. If I have understood you correctly: all PRIO staff initially supported the elected, rotating institute leadership, the staff meeting as PRIO’s highest body, and the egalitarian salary system, and thought these were good arrangements from a governing, political and ideological point of view – well suited to the radical 1970s. But after a while, it became apparent that researchers like Asbjørn Eide, Helge Hveem, Sverre Lodgaard and Marek Thee no longer supported these arrangements?

These four withdrew their support. Tord Høivik and I still supported the system. It would not have been possible to introduce such arrangements at PRIO in the early 1970s if it did not have near-unanimous support from the research staff. All of this was based on ideology, inspired by the radical currents in the 1970s. Such ideas were shared by many in academic life.

Another factor that favored the egalitarian tradition in decision-making was that our research was – and still is – to a large degree driven by individual curiosity. It is not as if a big boss tells you, ‘here’s a project, now you are going to do this’. It is the individual researcher who most often initiates the project and struggles to get it funded.

The initiative comes from below, from the researchers, and they also run their projects themselves. Consequently, it is not such a far-fetched idea that the researchers should also decide and run the entire institute. As long as you abide by the law and do nothing that is illegal, the staff meeting should decide, and the board should only have a controlling function. I am proud that we managed to get the authorities to accept our radical salary system. The trick was to conclude a collective wage agreement. All our staff joined the civil servants’ union (Norsk Tjenestemannslag). Our counterpart in the wage negotiations was the employer, and that was the staff meeting! So, the same people were on both sides of the negotiations, but in different roles. The wage agreement was signed by the institute leader, on behalf of the staff meeting, and by the leader of the local branch of the trade union, who was never the same person. This system was eventually recognized by the authorities.

[O]ur research was – and still is – to a large degree driven by individual curiosity. It is not as if a big boss tells you, ‘here’s a project, now you are going to do this’. It is the individual researcher who most often initiates the project and struggles to get it funded.

Would you say that you supported these radical principles longer than the other researchers at PRIO?

That’s right. Among the six researchers with permanent positions, four withdrew their support from the system around 1980. Then, in the middle of the 1980s, Tord Høivik changed his mind. I tried to persuade him and the others to continue with the flat structure, and I probably used some harsh words that I should have avoided, but it was in any case a lost cause.

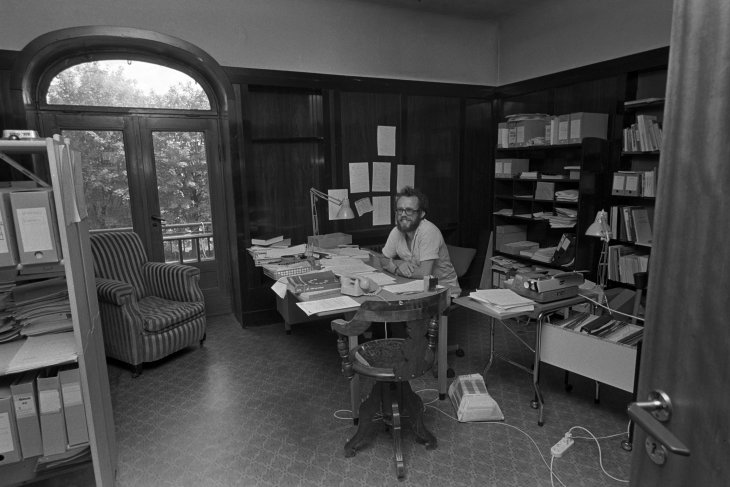

Tord Høivik at PRIO’s office in Tidemands gate 28 in 1973. Photo: Ole Christiansen / NTB Scanpix

We have now definitively reached the peak of your academic – and public – life: the struggle against secrecy, which includes of course the object of this secrecy – to what extent Norway was a part of the American nuclear strategy and which Norwegian politicians knew or did not know about this highly sensitive issue. This is a complicated matter, so I suggest that you inform us step by step about both stages: first, the one beginning in 1971, and then the stage from February 1979. The first part of the drama was about Omega and Loran-C, Anders Hellebust, the Schei report and a book published by Pax.

As you say, we were fighting a battle on two fronts: On the first, it was important to us to convey to the public that Norway was more integrated into the United States’ nuclear strategy than the Norwegian government wanted to admit. My main target was actually not the Norwegian membership of NATO, but the bilateral relationship between Norway and the United States. On the second front, we were fighting against exaggerated secrecy in Norway, where military information was routinely classified even though it could be found in open sources in the US. Politically, like many other leftists, I was opposed to Norway’s membership in NATO. We were above all critical of the nuclear doctrine which allowed a possible first strike. Omega was the first concrete case that I worked with.

What was Omega?

Omega was a US system for global navigation, which became operative in the beginning of the 1970s. The very-long-frequency radio waves from Omega could pass through water and the system was therefore suitable for sending signals to submarines in a submerged position. I was made aware of this through correspondence with some people in New Zealand, who had contacted an American friend of mine at SIPRI in Stockholm. The New Zealanders had concluded that Omega had been deployed in order to send navigation signals to strategic submarines with nuclear weapons directed against targets in the Soviet Union.

Why did the submarines need this? Because when a long-range missile is fired from a submarine at sea, rather than from a land base, the submarine does not know precisely where it is. It needs advanced systems of navigation in order for its missiles to hit even extended targets such as Leningrad or Moscow. When I started to look into this, I found that the Norwegian government decision to permit the building of an Omega station in Norway had been made in the absence of any public debate. This was surprising, given that the Omega station could integrate Norway directly into US nuclear strategy.

What is fascinating with you is how you come to be interested in such topics in the first place. You talk to an American researcher at SIPRI who knows someone in New Zealand – and then, you go start reading Norwegian Parliament documents to figure out whether this had caused any debate in Norway … right?

I had been interested in Norwegian alliance policy for some time, and I had written a book together with Sverre Lodgaard called Krigsstaten Norge (Norway, the Warfare State). I also knew something about such topics from home. As director of the Norwegian Geographical Survey, my father was upset because the mapping of Norway had been changed due to military considerations. Coverage of two poorly mapped areas, in Sunnmøre and in Setesdal, was postponed because NATO and the US wanted newer and better maps in other and militarily more important parts of Norway. Prioritization of Norway’s own mapping was thus to a large degree dictated by US military considerations.

When I learned about Omega, I thought that here we had another example of military considerations getting first priority. But to what degree did such projects influence Norwegian security? After all, they were in support of missile submarines with nuclear warheads. Ten years earlier – at the end of the 1950s – there had been a huge public debate about whether Norway should permit peacetime stationing of nuclear weapons. The conclusion was a ‘no’. Now I thought that Norway was perhaps indirectly contributing to American nuclear strategy through the Omega system, and I asked this question in an op-ed in Dagbladet [a major Norwegian newspaper].

Nothing more happened, I believe, until Anders Hellebust showed up at the next stage of the story?

Anders Hellebust was a former Secretary General of the Conservative Party’s youth organization. He had graduated from the Defence College (Krigsskolen), and he now worked for military intelligence. However, the Norwegian military wanted its staff to acquire higher academic education. For this reason, his employer sponsored Hellebust to take a graduate degree in political science.

For his thesis, he chose to write on the development of military infrastructure in Norway, with three cases: Omega, Loran-C, and the decision to locate Trondheim airport at Værnes. When Anders contacted me, I was obviously interested in his topic.

Loran-C was also a navigation system, but it had shorter range and its low frequency signals did not go as deeply into the sea as Omega. Two Loran-C stations had been built in Norway in the 1958–60 period. Neither we in Norway nor our contacts in New Zealand knew about this. But after a while, I started to cooperate with one of the New Zealanders, Owen Wilkes, who was more familiar with military navigation systems than I was. Later I brought him to PRIO.

We found that although Omega was initially meant to help the submarines navigate, it was not accurate enough to allow missiles to be properly targeted. Then we discovered that the Loran-C stations in Norway were built as a part of the US strategic submarine program. Specifically, they were meant to contribute to precise navigation for the Polaris submarines, the first generation of submarines carrying long-range ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads.

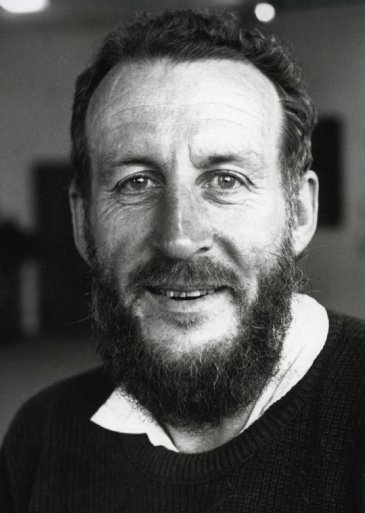

Peace researcher Owen Wilkes in 1990. Photo: South Canterbury Museum, Timaru Herald Photographs, reproduced with permission

Two Loran-C stations were built on Norwegian soil – one in Bø in Vesterålen and one on Jan Mayen island. By interviewing a number of officials in Norway, Anders Hellebust concluded that the building of these two stations were built in support of the Polaris program. Through technical journals like Journal of Navigation and hearings in the US Congress on the defense budget, Owen Wilkes unearthed information that substantiated this claim.

In 1966, the United States had passed a Freedom of Information Act which permitted the public to request the declassification and release of documents from government agencies. After the Watergate scandal and all the revelations of misconduct by US intelligence, the law had been strengthened and had become a very important tool for extracting information from US sources. We contacted various US government agencies with requests for the release of documents on Loran-C and other military systems of relevance for Norway.

[W]e discovered that the Loran-C stations in Norway were built as a part of the US strategic submarine program. Specifically, they were meant to contribute to precise navigation for the Polaris submarines, the first generation of submarines carrying long-range ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads.

In the first pile of documents we received from the US Department of State, there were several minutes from conversations between the US Ambassador to Norway and Norwegian Foreign Minister Halvard Lange. But everything concerning the Polaris program had been blanked out, except the headline on the very first telegram. It read: ‘Subject: Polaris Program’. We moved on from there and were able to get more information released.

In the meantime, in 1974, Anders Hellebust’s dissertation had been completed, and he wanted to publish his main findings. They were published in a major article in the Labor Party newspaper Arbeiderbladet. The article created a huge stir, not least because of Anders Hellebust’s military position. This outdid – by a wide margin – an op-ed in Dagbladet by a leftist peace researcher like me.

The Norwegian authorities made an unsuccessful attempt at collecting all copies of Hellebust’s dissertation, but I made extra copies and handed them over to members of parliament and others, in order to prevent the dissertation from ‘disappearing’. This was, of course, before the days of the internet, where everything can easily be distributed worldwide.

The uproar caused by the dissertation’s findings was so loud that the government found it necessary to begin a formal inquiry into the whole affair, led by a committee headed by Supreme Court Judge Andreas Schei. Professor of History Magne Skodvin was also a member of the committee.

The committee concluded that in 1958, when the first Loran-C station had been built, no one in Norway knew that it was related to the Polaris program. In 1960, though, the Americans found out that the coverage from the existing stations did not provide sufficient accuracy. Consequently, and in a hurry, a new station was built on Jan Mayen. When the building of this new station was approved by Norway, the government’s security committee received some information about the Polaris program.

Among others, Einar Gerhardsen, Prime Minister at the time, had noted that it would be possible for Norway to ‘help with defensive arrangements of this kind’. In other words, the use of nuclear weapons was seen as a defensive arrangement.

The report from the inquiry was classified and only an unclassified summary was released to the public. In this version, the sensitive reference to strategic submarines had been excised. The report concluded that the decision-making process had been satisfactory, and that there were no grounds for criticism.

However, all members of the Norwegian parliament (Stortinget) received the full, classified version of the report. Before it was discussed in parliament, Finn Gustavsen, an MP from the Socialist Left Party (SV) consulted me. He asked me to read the classified report. I pointed out the sensitive issues, as well as where and why the edited, censored, report was misleading. But how could we get this information out to a broader audience?

The debate in parliament would take place behind closed doors. First, a small leak appeared in the Socialist Left Party’s newspaper Ny Tid, probably due to another member of parliament from the Socialist Left Party. Then I decided that I wanted to get the entire classified report published. I managed to obtain a copy of Finn Gustavsen’s copy of the report, put a lot of work into removing his comments in the margins, and then released a copy to Pax publishing house.

You copied a classified report on your own initiative?

I understood, of course, that copying a classified report was controversial, and might even be deemed to be illegal. The classified report was published as a book and all the classified sections were marked, so that readers could see what had been removed from the published summary. A vertical line and an H [for ‘hemmelig’, meaning ‘secret’ in Norwegian] pointed out all the most sensitive sections.

This made for very intriguing reading. I did not at the time admit publicly that I was the source of the release of the classified report, but I wrote a postscript to the book. In 2009, in Gudleiv Forr’s book Strid og fred, written for PRIO’s 50th anniversary, I finally confirmed my direct responsibility for publishing the secret report.

I understood, of course, that copying a classified report was controversial, and might even be deemed to be illegal. The classified report was published as a book […] This made for very intriguing reading.

To put it mildly, there are more intriguing details to this story. Pax published the Schei report as a book on the same day as the two parliamentarians Finn Gustavsen and Berge Furre started to read aloud from the secret report?

The two of them decided to breach their duty of secrecy, and the party organized a public meeting in Oslo where they read aloud from the classified report to a large audience. They did not know that the book would be published at the same time.

Because that was a result of your personal decision. Your work behind the scenes?

This was a result of my independent initiative. Finn Gustavsen said many years later that he had not understood that it was his copy of the report that had been copied. The Minister of Defense quickly went public with a statement that the publication of the classified report did not pose a risk to national security. As a consequence, there was no basis for any trial against anyone involved in publishing the book.

Norwegian parliamentarians Berge Furre and Finn Gustavsen making public the secret parts of the government’s report on Loran-C and Omega in 1977. From left: Berge Furre, Finn Gustavsen, Reidar T. Larsen and Bjørgulf Froyn. Photo: Arbeiderbladet / Arbeiderbevegelsens arkiv og bibliotek

However, the politically sensitive question at the core of this story is: did the Labor government, including Foreign Minister Lange, know why the US wanted a Loran-C station built in Norway in 1958?

On 19 May 1958 the US Ambassador [Frances E Willis] visited Halvard Lange with an urgent request: the US wanted to build a Loran-C station in Norway. She told Lange that this was related to the Polaris program. In the telegram she sent to the State Department after the meeting, she affirmed that she had only said this verbally to Lange. Nothing about Polaris had been included in the written memorandum she handed to him. The Schei committee cited this memo extensively, and there was nothing in it about the Polaris program.

But because Owen Wilkes and I used the US Freedom of Information Act to get access to the correspondence between the US Embassy and the State Department, we found confirmation that Polaris had indeed been mentioned in the meeting. We also found that, in 1960, the same Ambassador came to Lange and asked for permission to have one more station built, in the Jan Mayen island. In a second meeting on this request, Lange if this was related to the program they had discussed two years earlier. Thus, it seems that Lange either remembered the previous discussion or had a memo of his own about it. And it was this information – in 1960 – that finally found its way to the government’s security committee.[2]

What remains unclear is how many people Lange shared this information with in 1958. Did he inform Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen, or did he not? Anders Hellebust concluded in his dissertation that Norwegian civil servants had misled the politicians, since many officials were aware of the connection between the Loran-C and the Polaris program. However, Hellebust did not at that stage know that Halvard Lange had been informed by the US Ambassador.

My interpretation is different from Hellebust’s: this was cleared at the top political level. If anyone was misleading anyone, it was Halvard Lange who misled the rest of the government. But this we do not know. It has not been possible to verify. But it was definitely not a case of civil servants leading the politicians astray.

Halvard Lange in 1967. Photo: CC BY-NC-SA / Kraftmuseet – Norsk vasskraft- og industristadmuseum

My interpretation is [that] this was cleared at the top political level. If anyone was misleading anyone, it was Halvard Lange who misled the rest of the government. But this we do not know. It has not been possible to verify.

I imagine that the more sensitive part of this story is linked to Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen’s speech at the NATO meeting in 1957. In this speech, he proposed postponing the decision over whether bases for intermediate-range nuclear missiles should be established in Europe. It is also linked to decision of the Labor Party’s decision at its National Convention in 1961 that nuclear weapons should not be deployed on Norwegian soil in peace time.

Yes, and with explicit reference to Gerhardsen’s 1957 NATO speech, the so-called Easter Revolt took place in 1958, when a majority of the Labor Party’s parliamentarians signed a petition initiated by socialist students against the deployment of intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe.

Obviously, when the US Ambassador shortly after the Easter Revolt asked Halvard Lange for permission to build a navigation station in Norway that was related to strategic nuclear weapons, this was very sensitive. So, I understand perfectly well that he kept this secret, but …

… this was unacceptable to the peace researcher Nils Petter Gleditsch?

At least 19 years later it was.

So, you decided to reveal something that was highly politically sensitive? You wanted to disclose these secrets as you saw them as a breach of Norwegian nuclear and base policy?

At least undermining it. When it was revealed that Norway had participated in a project that was related to strategic nuclear weapons, this created a stir. But the political elite in Norway were unapologetic. They were in favor of this arrangement. I have always claimed that the main reason for this was that the politicians saw this as a kind of exchange: Norway is a member of NATO, and we receive our military protection from the United States.

So, to a certain degree, we live under the US nuclear umbrella. It is not surprising then that the US wants something in return: they want help from Norway and other member states to maintain the nuclear deterrent. But the Norwegian political elite was reluctant to admit that this was the case.

A banner against nuclear weapons on Norwegian soil in the May Day parade, 1 May 1962. Photo: CC BY-NC-ND / Arbeiderbevegelsens arkiv og bibliotek

The second part of this drama started in February 1979?

Actually, it started a little earlier. After we had been working with Loran-C and Omega, we looked around for other projects and installations in Norway that might be connected to US nuclear strategy. Then we were inspired by the so-called ‘lists case’. Ivar Johansen was an activist in the peace movement. He had gathered a lot of material on the Norwegian intelligence services and had mapped out where several military intelligence stations were situated by using the phone book, the number of votes in ballots in certain sections of the civil servants’ trade union published in their journal Tjenestemannsbladet, as well as other sources.

He and several others were put on trial accused of a violation of the national security clauses in the Norwegian penal code. We were asked to testify in the trial and wanted to follow up and use the same methods as Ivar Johansen. We did so a bit more systematically and recorded our findings in detail. Among other things, we visited the office where Televerket (the national phone company) held their collection of old telephone directories in order to find out when the various stations started up. We just perused the catalogues and worked our way backward until they appeared.

These were military installations?

They were installations for various kinds of signal intelligence, radio signals, and other forms of electronic information. In Karasjok in the far North, we found a station registering radioactive fallout from nuclear tests. They were generally listed in the phone book as ‘Defense stations’.

Did you travel around to take a closer look at these stations?

Yes, we did. As a point of departure, we reckoned that what could be seen from publicly available places could be regarded as open sources. Then we combined what we were able to see with information from military handbooks, technical journals, and US congressional hearings. We wrote a report as a basis for my testimony as a witness called by the defense lawyers. The idea was to show that the information that Ivar Johansen and others had collected could not be characterized as secret. The detailed report was released just before I went to testify at the trial. Two years later, the report was published in a book, Onkel Sams kaniner (Uncle Sam’s Rabbits[3]) by Pax.

All hell broke loose. We were accused of being traitors, and very few dared to support us – or at least to say so in public. Since Norway’s policy on foreign bases precluded the establishment of foreign military bases in Norway in peacetime, Norwegian authorities remained cautious about allowing too many US military personnel to stay in Norway at the same time.

Therefore, these stations were mostly operated by Norwegian personnel, although they were built on US initiatives, and the operating expenditures were fully funded by the US. We assumed that the collected data were transmitted directly to the US. We also tried – on the basis of military and technical literature – to assess what military function each station might have, and we came up with the hypothesis that one of them tapped radio traffic from foreign embassies in Norway. All of this was basically unknown to the Norwegian public.

However, when the report was published, it also caused major problems at PRIO. The majority of the researchers were strongly critical of our report. This were the same people who by then were opposed to the egalitarian salary system and who were critical of my role in getting it prolonged. Therefore, the publication of the report exacerbated the polarization at PRIO.

It was suggested that I should take an unpaid leave of absence; luckily, I turned this proposal down, and decided to ride out the storm. Those days were difficult and tough. In retrospect, I can see that I had not been sufficiently careful to inform the other researchers at PRIO about what we were doing. In addition, there was a genuine fear among several of my colleagues that PRIO would suffer, politically and even economically.

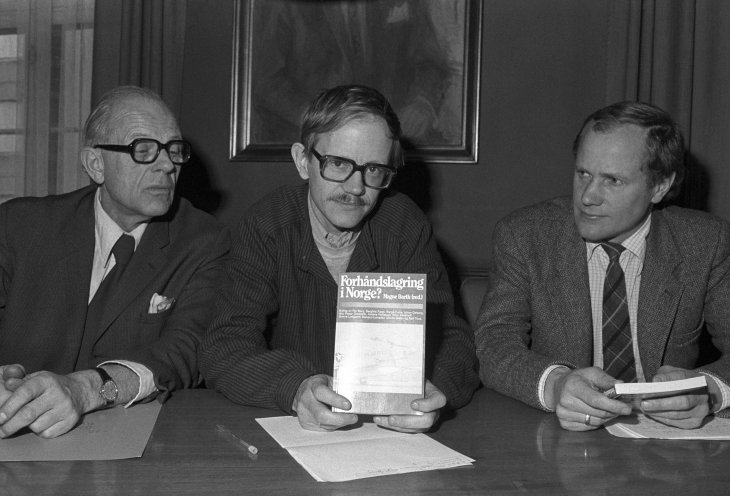

Rolf Thue, Nils Petter Gleditsch and Anders Hellebust at a book launch in 1980. Photo: Henrik Laurvik / NTB Scanpix

So, you found yourself in the eye of the storm, internally at PRIO as well as beyond?

Definitely! After a while, I was called for questioning by the police, and then both Owen Wilkes and I were formally charged with violating the penal code provisions on national security. It took well over two years before our case came to trial in May 1981.

As you saw it, what created this storm was that you had put together publicly available information, using open sources?

The crucial point was that even though each piece of information was publicly known, when the pieces were put together a picture emerged that had to be kept secret, according to the government, out of concern for national security. This was the so-called ‘pieces of the puzzle’ principle. On its own, each piece was innocuous, but put together they created a picture that was classified as secret. Before the ‘lists case’ and our case, the puzzle principle had been invoked in the national security cases against Soviet spies, in 1954 and in 1968. In both cases, the accused were found guilty, and their convictions were upheld by the Norwegian Supreme Court.

As I saw it, the principle was highly problematic, whether seen from a perspective of freedom of speech or freedom of research. As noted, in 1979, few people supported our view. However, when our case came to court in 1981, public opinion had changed to some degree. Some parliamentarians, like Reiulf Steen (who had just stepped down as leader of the Labor Party) and former parliamentarian Gunnar Garbo from the Liberal Party, supported us. So did some newspapers, which agreed that the puzzle principle was problematic.

However, we had done one thing that was actually more directly illegal: we had taken pictures and drawn sketches of the antennas we could see from publicly accessible places, and compared them with the ones we could find in Jane’s Military Communications and other handbooks. This was in breach of another law, a law on military secrets from 1914. At these places, there were signs saying that the law on military secrets was applicable. I have to admit that I had never bothered to read the law on military secrets because I regarded it as being of no interest.

It was first when I understood that we actually would go to trial that I realized that technically we had broken the law. Normally, such a violation of this particular law would not have led to a very severe reaction. But when this violation was combined with the puzzle principle, the prosecution had a stronger case for applying the national security sections of the penal code. As one of our sources was illegally obtained, the combination of publicly available information was no longer the only issue.

We managed to contribute to the debate about official secrecy. But regrettably, we did not manage to generate much discussion about the extensive intelligence activities that were taking place on Norwegian soil, funded by the United States for strategic purposes, outside of the NATO framework. In Oslo City court we received a suspended sentence, six months in jail, and we had to pay the legal costs.

Because of the report on intelligence stations, right?

The sentence was appealed by us as well as by the prosecution. The case came up for the Supreme Court eight months later. The city court verdict was upheld, but two of the five judges voted for an unconditional prison term.[4] The money for the fine and court costs was collected by our supporters.

What was it like to be in the eye of the storm – how did you cope? It must have been a burden on your shoulders, and for PRIO, too, which after the trial was branded as a hippie, radical, spy institute?

There were moments when I wondered whether PRIO would be shut down as a result. It soon became clear that the Labor government would not withdraw the public funding for PRIO. But in the autumn of 1981, Norway got a new Conservative government. The Ministry of Culture and Research appointed a committee to evaluate Norwegian research in international relations and peace. The mandate of the committee was not designed to shut down PRIO. In its recommendations, the committee made several critical comments about PRIO, including criticism about its governing structure. But the criticisms did not point out any major problems. We had been nervous that it might. And it was a heavy burden for me, of course it was. I should not pretend that I’m tougher than I am.

These must have been trying times for you personally. After all, your colleagues at PRIO criticized you publicly. You must have felt stabbed in the back by your colleagues and employer? I find this rather extraordinary …

But I also had support from many at PRIO. And this public dissociation from a majority of PRIO’s tenured researchers could be seen as an attempt to protect PRIO and make sure that the public criticism would only target me. In a way, this could be seen as successful because the government’s financial support to PRIO was not cut off even though I was put on trial and convicted.

But still, you must have felt betrayed and stabbed in the back?

Yes, but in retrospect I see that I should have kept my colleagues better informed about my activities.

Nils Petter Gleditsch stood trial with Owen Wilkes in the Oslo City Court in May 1981 and then in the Norwegian Supreme Court in February 1982. Photo: Arne Pedersen / Dagbladet

But were they not informed about your research projects? Did they not know what you were up to?

Of course they knew, in particular Sverre Lodgaard, with whom I had cooperated closely on various publications about Norway’s base and nuclear policy.[5] But I think that when they saw the report and how detailed it was, they were genuinely surprised. If they had known beforehand, I might have been advised to cut some detail, making the report just tolerable for Norwegian authorities. This might have been sound advice.

Anyhow, this was the only time in my career that I became a public figure in Norway to the extent that my name appeared on humor pages and in newspaper quizzes. In one, readers were asked: ‘Who is Chief of Defense in Norway: Sverre Hamre, Sven Hauge or Nils Petter Gleditsch?’[6]

You were indeed a public figure. Even in my Christian, bourgeois town of Drammen, everyone knew who you were, including me. Long before I knew that I would come to PRIO and have you as my supervisor, I may not have known who the Chief of Defense was, but I certainly knew that it wasn’t you.

I will never forget that, in the summer of 1984, I sent a letter to Haakon Lie (Secretary of the Labor Party 1945–69) asking for an interview. After weeks with no answer, I acquired the courage to call him. Before I even got the opportunity to explain why I wanted to interview him, he abruptly said: ‘I know who you are, I have read your letter. I will not talk to anyone coming from that institute and certainly not the so-called researcher Nils Petter Gleditsch’. ‘That’s my supervisor’, I answered, and quickly added: ‘But you have never talked to me.’ ‘Right’, Haakon Lie said. ‘That doesn’t make it any better,’ and hung up.

Three minutes later, the phone rang in my office, and when I heard the voice, I almost fell off my chair: ‘Hi Hilde, it’s Haakon. I have been thinking about what you said about PRIO and that I had never talked to you. Please, come to see me at once, before I change my mind?’

After challenging extensive government secrecy and US strategic operations on Norwegian soil, your research moved away from this critical examination of the recent past? You started to work with the economic consequences of disarmament, and did so for the next ten–fifteen years, until you delved into the research area where you are now best known internationally: democracy and peace. You became a quantitative political scientist and made a huge breakthrough as an internationally recognized, topnotch researcher?

Much of this happened in parallel. The economic consequences of disarmament was a topic where PRIO had done some work in the mid-1960s. At the end of the 1970s, this topic returned to the public agenda, particularly in the United Nations, which focused on the relationship between disarmament and development.

I now think that tying development to disarmament was a dead end, but the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs was very interested in it. This opened up a source of research funding, and I published several articles and two books together with Olav Bjerkholt and Ådne Cappelen at Statistics Norway (SSB).[7] You know, I have always had a tendency to work on many things at the same time and have been criticized for spreading my research interests too thinly.

I would like to add that the rest of us at PRIO, behind your back, always talked about ‘Nils Petter time’, as opposed to normal time. The reason was that you always work long hours and get more done and published than the rest of us. But I digress! To return to your conversion to a quantitative political scientist exploring the democracy-and-peace theme, when, how and why did all this start?

In 1991, I was asked to step in for Peter Wallensteen for three months. He was Professor of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsal Universitya, and he was going on a sabbatical abroad. I had already been playing with the idea of returning to the core area of peace research: the study of armed conflict.

Peace researchers in Uppsala had been collecting data on armed conflict, though they only had data for a few years. Another problem was that they had no threshold for the amount of violence needed to categorize a dispute as an ‘armed conflict’. Therefore, Uppsala’s list of armed conflicts included some with only one fatality or ‘probably one fatality’. Some of their best students were working on this project, and we agreed it made sense to set a threshold of 25 battle deaths in one calendar year. Peter Wallensteen agreed as well, and that became the norm. As editor of Journal of Peace Research, I took the initiative to publish an annual update of data on armed conflicts.

The problem that remained, was the short time series, so there was little basis for looking at trends over time. However, a few years later the economist Paul Collier was appointed head of development research at the World Bank and started an ambitious project on civil war. PRIO was associated with that project and we received funding to expand the conflict data and in close association with Uppsala backdated the time series to 1946.

The idea was to create a new standard tool for empirical research on armed conflict. The field already had the data from the Correlates of War Project, but they covered only conflicts with a minimum of an accumulated thousand deaths over its full duration. We wanted a much lower threshold (25) in order to include more conflicts into the dataset, and we used the calendar year as our time limit, counting conflicts as ‘active’ only in years when they reached the 25 battle deaths threshold.

The article where we launched our new dataset, published in 2002, is by far my most frequently cited work. It is also the most cited article by Peter Wallensteen, in the Journal of Peace Research and by anyone at PRIO. The dataset became a standard tool, and researchers cite our article as a reference article for the dataset.[8]

Another thing connected with my stay in Uppsala turned out to have long-lasting implications. As part of a research seminar series, I decided to give a lecture on democracy and peace. I had been a bit reluctant to accept the thesis that democracies do not go to war against each other. However, when I read up on it I eventually concluded that the thesis was quite plausible.

The article where we launched our new dataset, published in 2002, is by far my most frequently cited work. It is also the most cited article by Peter Wallensteen, in the Journal of Peace Research and by anyone at PRIO. The dataset became a standard tool.

Work that I published with my research assistant Håvard Hegre – who today holds the Dag Hammarskjöld professorship in peace and conflict research at Uppsala University – generated a lot of interest. Our results were published just as the debate about the democratic peace really came to the fore.

This gradual change of your research interests probably also had to do with how you – as a political human being – were influenced by the changes in international politics at the end of Cold War… new themes came up under new conditions …

Yes and no. For me, this was partly a return to my earlier use of statistically oriented approaches.[9] At the same time, the end of the Cold War led to an increased understanding of what has been named ‘liberal theories’ on international politics, and a declining emphasis on power politics which had dominated the so-called ‘realist school’.

As a result of all this, a huge number of publications written by you or under your leadership and supervision, many of them in the Journal of Peace Research where you were editor from 1983–2010, linked democracy and peace, studied civil war, climate changes and conflict – and more.

After the end of the Cold War, there was renewed interest in the study of civil war. For years, peace research had mostly focused on inter-state conflict, perhaps since the Cold War raised the specter of a gigantic interstate conflict between East and West. But the number of interstate wars went down during the Cold War, while the number of civil wars increased and remained high even after the end of the Cold War, with several civil wars in the former Yugoslavia. Consequently, most battle deaths now occurred in civil wars.

Of course, the Korean War and the Vietnam War – the two bloodiest wars after the Second World War – also started as civil wars. In 2001, when the Research Council of Norway announced new funding for ‘Centers of Excellence’, we decided to apply for support for a ‘Centre for the Study of Civil War’. This turned out to be a winner and the Center was established at PRIO, led by my colleague Scott Gates. This led to the recruitment of many new prominent researchers, and many outstanding publications in the following ten-year period.

Some of the Centre for the Study of Civil War (CSCW) staff at PRIO in 2008. Photo: Marit Moe-Pryce / PRIO

But this was your international breakthrough as researcher?

Yes, you might say that. PRIO was already well known among leading international peace and conflict researchers. But it was a bit like ‘there is something going on in Norway as well’. From the beginning of the 1990s onward, our research was taken seriously internationally and accepted as an important contribution on its own merits and not only as a ‘Norwegian contribution’, as it is sometimes called in Norwegian journal articles. And Journal of Peace Research regained much of the prestige it had had in its first years, when it had been among the very few journals dealing systematically with issues of war and peace and had published several groundbreaking articles by Johan Galtung.

You were the driver behind much of this research internationally. Suddenly, researchers all over the world looked to the Journal of Peace Research, to PRIO – and to you. And in this context, I don’t know how you do it, but you have this tremendous ability – or instinct – for picking up the most talented young people for your projects.

Well, that’s something I may have picked up from Johan Galtung, who was a mentor for my generation. But it is probably also related to limited ability to say no. When people come to my office, I am reluctant to say, ‘sorry, I have no time, I have a lot of work to do’, instead of listening to what they have to say. One example is Indra de Soysa, now professor of political science at NTNU in Trondheim. At the end of the 1990s, the reception at PRIO called me one day and said: ‘There is a guy from Sri Lanka who would like to talk to you.’ Our initial conversation led to years of fruitful cooperation. This goes for several people, whom I have ‘picked up’, to use your wording.

Well, I am another example. And there are several people you can add to the list of young aspiring historians who all had you as their supervisor: Stein Tønnesson, Tor Egil Førland, Olav Njølstad, Nils Ivar Agøy, Odd Arne Westad, and others!

I cannot take any credit for Stein Tønnesson or Odd Arne Westad. Their supervisors at PRIO were Marek Thee and Tord Høivik …

OK, minus Stein and Odd Arne, but what about all the people you recruited to quantitative political science?

Oh, that is related to something else that happened in 1991. One day, Ola Listhaug from NTNU came into my office and said that he was going to start up studies in political science in Trondheim. Like me, Listhaug was a sociologist who had converted to political science. He sought my advice as to whom I could recommend as applicants to the new positions. There was also a part-time chair (Professor II) in international relations.

After some discussion, Ola asked if I wouldn’t consider applying myself. I answered, as was true, that I did not even have the foundation course (grunnfag) in political science, but Ola Listhaug said that this did not matter. I got the position and created a new course called ‘causes of war’. To our surprise, there were lots of students in Trondheim who were interested in international relations generally and war and peace specifically. Several of them, such as Helga Malmin Binningsbø, Halvard Buhaug, Ragnhild Nordås, Siri Aas Rustad, Håvard Strand, and Gudrun Østby (again, in alphabetical order!) were at some point recruited to PRIO.

What about PRIO’s current director, Henrik Urdal?

That is a different story. He was a student in Oslo and had decided that he had spent enough time in politics – among other things, he had been secretary of the Socialist Left youth organization – and he needed to find a suitable topic for his master’s thesis. So, I suggested a theme that suited his background as a demographer. I knew of him because he had worked as a researcher in Statistics Norway SSB, where my wife had been his boss. I have occasionally teased my wife by telling her that I stole one of her most skillful recruits.

Well, I insist that what you call coincidence, is a knack for recruiting clever researchers. You know, I have never escaped from your little green felt-tip pen, correcting everything I wrote, giving valuable comments, down to where I should put the comma. You understood structure, you understood how to make an argument, you understood what I had the necessary evidence to claim or not, and you understood the importance of publishing internationally long before most others in academia in Norway. I remember you told me: ‘Hilde, your Norwegian books are good, but now you must stop writing in Norwegian and publish your findings in English-language journals internationally.’ In addition, you stressed the importance of getting research funded.

I agree as far as international publication is concerned. I was keen to get our work out to the international research community.

To conclude: is it a coincidence that your research can be divided into phases that coincide with political developments internationally?

No, that is no coincidence. We have talked about democracy and peace, and if you read my older publications, you will find very little about democracy, but a lot about equality, justice, and peace. The idea of a liberal peace, built on ties through international trade, became a major theme in peace research at the end of the 1990s. I was actually skeptical in the beginning, even after I had embraced the idea of a democratic peace.

But I have come to realize that economic cooperation and development are important drivers of peace. Therefore, I have moved in the direction of supporting liberal principles. I find it difficult today to call myself a socialist given all the crimes that have been committed in the name of socialism. However, I have no problem calling myself a social democrat. The idea of the liberal peace was followed, for some, by the capitalist peace. The reasoning is that a market economy is a precondition for democracy, and market economies are a precondition for economic cooperation internationally.

I have actually tried to launch a new formula for stable peace, ‘the social democratic peace’, combining democracy, a strong state, economic development, international political and economic cooperation, and non-discrimination of minorities. I think this makes a lot of sense as a policy, but I must admit that as a slogan that it has fallen flat.

If you look at the political realities, the wind does not seem to be blowing in the direction of a social democratic peace.

At least not as a political program. In 2016, when I published my book on a more peaceful world,[10] which in many ways may be regarded as my intellectual testament, I had learned that when you publish a book you need to promote it actively. I managed to publish three op-eds on themes from the book in leading outlets like Aftenposten, Dagens Næringsliv, and forskning.no.

But my fourth op-ed was rejected. It was about the social democratic peace, which I sent to the labor newspaper Dagsavisen. I never got it published. It is still on my hard disk in the ‘unpublished’ folder.

Thank you very much, Nils Petter.