The Women, Peace and Security Index is one of the most comprehensive measures of women’s well-being around the world. This collaboration between PRIO and the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS) goes back to 2016. Funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Index ranks countries based on indicators of women’s inclusion, security, and access to justice. The updated 2019 report includes 167 countries.

Here, GPS Director Torunn L. Tryggestad talks about the genesis of the project. Marianne Dahl, who is heading PRIO’s part of the project, highlights some of the nitty gritty details of the Index, including which countries have improved, and which have fallen dramatically down in the rankings.

Girls and boys train and play sports together in Niger. Photo: Association Sportive Les Volcans via Flickr CC

An Innovative Approach

The project began in 2016, when GIWPS approached PRIO. “They had this idea of developing an index on WPS and wondered if we were interested in partnering with them,” Torunn L. Tryggestad explained. “The initial idea was to collect new data. We discussed a little back and forth and our advice was to not develop a new index from scratch but rather look at all the numerous indexes that already exist on women’s status and empowerment and explore if these could possibly be combined in new and interesting ways.”

The first Index was launched in 2017 and immediately made headlines for which countries were on top, and which had ranked at the bottom, showing where in the world it was “best” or “worst” to be a woman. Part of what makes the index unique though is the inclusion of the security aspect.

The way we have managed to combine indices from the gender and development communities together with those from peace and security in the WPS Index is what makes it particularly interesting and innovative.

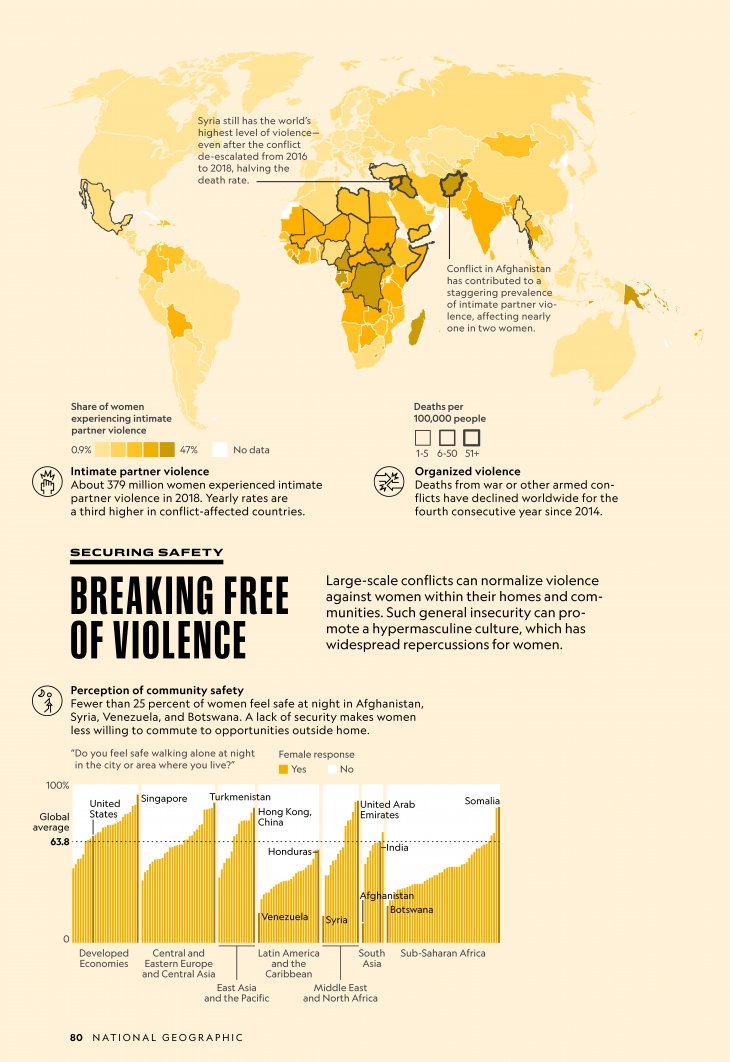

“PRIO suggested to include conflict data or organized violence as a key dimension in the new index. This has been a pet project of mine since I got involved in scholarly work on women, peace and security,” says Torunn. “What is also innovative is the way we approach ‘security’ by looking at women’s security on three levels: the family – intimate partner violence; the community – sense of security in the local community; and the society – organized violence.”

The security component became one of PRIO’s key working areas, lending new insights to the project.

The interdisciplinary, global characteristics of the Index make it something special in the areas of study it covers.

“We need to build bridges between the women/gender studies communities and the peace and security studies communities. For way too long these communities have operated in separate silos. The way we have managed to combine indices from the gender and development communities together with those from peace and security in the WPS Index is what makes it particularly interesting and innovative,” says Torunn.

Security and Well-Being: PRIO’s Piece of the Puzzle

Marianne Dahl and I sat down to talk about the updated and then yet-to-be released WPS Index last week. Our conversation appears below (with some light editing when we got a little too far into the weeds of the data).

When I talked to Torunn she told me about how this project got started. Since then though, you’ve been working with the data itself on PRIO’s side of things. What is it you do?

One of PRIO’s key contributions is in the security dimension, which I personally think is the new and innovative part of this index, and which makes it different from the other gender indexes which are already out there. Other indexes tend to focus more exclusively on development aspects. The WPS index is novel in two ways in particular: first, that we are including the security aspect; and second, that we look at absolute scores. Rwanda, for example, is ranked as number five in the Global Gender Gap Index because there’s gender parity – girls are not in school for very long, but neither are boys. We wanted to shift the focus to how long girls are in school, independent of boys. If girls are in school for just a couple years, but so are boys, the country will score well. But really that’s not long at all, even if it’s “fair” in that country. That’s one thing our absolute scores reveal in the rankings.

But what about the comparison in society – how much girls are valued, for example?

Well, we also capture the unfairness, the gender difference aspect. One thing we look at is son bias. It’s a birthrate measure of how many girls are born compared to how many boys are born in the country. When everything is natural, when there’s no gender bias in the abortion rate, there should be a few more boys than girls, because boys have a higher risk of dying in their first few years. It’s nature’s adjustment feature.

But in some countries, there are not a few more boys. There are a lot more boys. In China, in India, for example. Not only is this problematic in itself, but it also serves as a signal of society’s general appreciation of boys and lack thereof of girls. We also include surveys on the percentage of men who are OK with women working. These variables show gender injustices in society.

But when it comes to education, we just want to see how long girls can stay in school, because that number adds to their overall well-being. We’re comparing girls’ education duration to other countries around the world, instead of just within each country.

You say the security aspect is unique with this index. Can you talk about some examples of countries that are strongly affected when you add in the security factors?

We’ve looked at how a given country would do if we constructed the index based on only two of the sub-dimensions: inclusion and justice. If we had done it that way, the index would be much more comparable to other, existing indexes out there. If we leave out the security dimension, two countries such as Singapore and Venezuela become very similar, ranking as number 43 and 47, respectively. If you want to capture how it is to be a woman in these countries, you can’t only focus on inclusion and justice. Those are important, but if girls don’t feel safe as they walk home from school, if women are often sexually abused, or experience violence in their partnerships, that affects their lives in profound ways. We need to account for these things when we produce an index of women’s well-being.

Copyright of NGP 2019. Used with permission from National Geographic.

If you want to capture how it is to be a woman in these countries, you can’t only focus on inclusion and justice. Those are important, but if girls don’t feel safe as they walk home from school, if women are often sexually abused, or experience violence in their partnerships, that affects their lives in profound ways.

When you look at Venezuela and Singapore, you see Venezuela is embroiled in political crisis. Only one in five women feel safe in their own neighborhood. While in Singapore, the number is as high as 94 percent. As many as 12 percent of women in Venezuela report they have experienced intimate partner violence during the last 12 months, while the number in Singapore is less than 1 percent. So when you take the security dimension into account, Singapore is ranked number 23, and Venezuela is number 84. That’s a substantial difference, and points to the importance of including the security dimension in order to obtain a comprehensive and accurate measure of women’s well-being.

So if you see these stark differences, why would one not take these aspects into account?

One thing could be data. Take as an example organized violence. That’s a key component that we include. But we don’t have gender-disaggregated organized violence data, meaning we don’t know if women or men are the victims in a conflict. There’s just not enough information in the news sources where we get our data from. Journalists will report “24 people were killed,” but many times they won’t report how many were men and how many were women.

It’s not necessarily a problem for us when we work on this index though. For example, take the crisis in Syria. Independent of whether the majority being killed are men or women, the conflict imposes immense suffering on the women who live there. If it was only men who were killed, women would still have to live through the sorrow of losing their sons and partner, and with this having to take care of their kids all on their own. But all of this is to say, this could be one reason security might not be included when measuring women’s well-being.

Still, there are security aspects that we cannot pick up on in the Index because we don’t have data for that. Homicide, for example, is something we would ideally include in the Index, but the current state of the homicide data is too poor to include. Still, a lot of these security aspects go hand in hand. For example, high homicide levels will make women feel unsafe in their own neighborhood, which we do pick up on. Also, there might be more intimate partner violence if homicide rates are high, so we will pick up on some of that. Still, some countries are going to do better than if we had been able to include those measures. The US, for example, is a country that probably benefits from not including homicide rates, because levels are quite high there.

Positive Change Overall

Were there any surprising changes this year in the rankings?

The big overall change is positive. 59 of the countries improve by five percent or more of their score from the last Index rankings. Only one country, Yemen, fell by five percent. So most countries are moving in a positive direction. Eight countries improved by more than ten percent, including Moldova, Latvia, Malaysia and Benin.

Saudi Arabia has a lot of money, but women just gained the right to watch football.

But then you have the largest drops. Myanmar moves 31 places down. The big change is the organized violence against the Rohingya Muslims. It’s a depressing move, but you want the Index to pick up on changes like this.

What’s really interesting though is to look at the countries that do better or worse than their income status would indicate. Rich countries generally do better than poor countries. But some countries do much better than their income rank. Rwanda, for example, improves a lot compared to its income ranking. It’s ranked 144 with GDP per capita, but the Index ranking is 65. The same goes for Zimbabwe, Jamaica, Nepal, Moldova, to name a few. All these countries score much better on the Index than on their GDP per capita.

And then you’ve got the opposite.

Yes, with Saudi Arabia. Which is maybe not that surprising. A lot of money, but women just gained the right to watch football.

And then Libya, Kuwait. These are mostly oil economies at the bottom here, with gender-unfriendly policies but a lot of money.

Finally, how did Norway do this year in the rankings?

Norway wins this year, which is almost a bit embarrassing because the Index is funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But this is not part of a secret plan by a country with a population of five million to take over the world.

Not yet.

Not yet!

[…] it is to be a woman in these countries, you can’t only focus on inclusion and justice,” Dahl said in an interview with PRIO. “Those are important, but if girls don’t feel safe as they walk home […]