US Congressman John Lewis gave the PRIO Annual Peace Address 2011. Lewis has been a Member of the US House of Representatives for the Fifth congressional district in Georgia since 1987. He was a prominent leader in the nonviolent civil rights movement in the early 1960s and President Obama has recognized his role as a source of inspiration. In February 2011 John Lewis was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest US public award for civilian service. See also the 2015 marking of the 50th anniversary of the historic civil rights march in Selma.

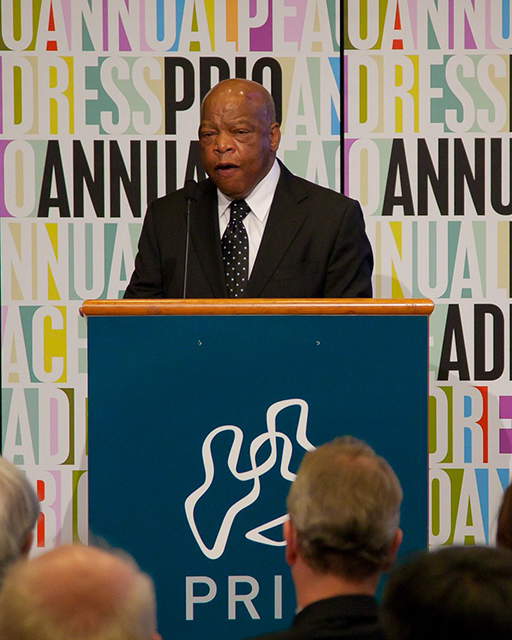

John Lewis giving the PRIO Annual Peace Address in 2011.

Below is a transcript of John Lewis’ Peace Address at PRIO.

The Role of Non-violence in the Struggle for Liberation

I am deeply honored and very delighted to be here today at this prestigious institution, the Peace Research Institute Oslo. I want to thank Director Kristian Berg Harpviken for inviting me and Professor Nils Petter Gleditsch for his tireless efforts to ensure that this journey would come to pass.

At PRIO you study the work of peace. You verify the work of non-violence, and you quantify the approaches that help create peace in our world. You have contributed so much to the growing body of research that confirms the power and potential of peace to heal the conflicts of our time. You know so much about resolving conflict between nations and people. You know how people can live in peace in our society. And you have ideas about how to implement the ways of peace as public policy. With all this profound knowledge and understanding you have stored in all the minds in this room, it led me to ask myself: I wonder what these brilliant scholars know about chickens?

Some of you have heard the chicken story while I have been here. Some of you probably heard it in 1966 [John Lewis spoke in Oslo at a meeting organized by the Norwegian Students Association in the spring of 1966]. I grew up in a farm in rural Alabama, about 50 miles from Montgomery. My father was a sharecropper, a tenant farmer. But back in 1944 when I was four years old – and I do remember from when I was four; I really do – my father had saved 300 dollars, and with 300 dollars he bought 110 acres of land. And on this farm we raised a lot of cows and hogs. We grew cotton, corn, and peanuts. We raised a lot of chickens, and it was my responsibility to take care of them. And I fell in love with raising chicken like no one else could raise chicken. I would take the first eggs, mark them with a pencil, place them under the sitting hen, and wait three long weeks for the little chickens to hatch. Why? Well, from time to time, another hen would get into that nest, and there would be some more eggs, and you needed to separate the fresh eggs from the eggs that were already under the sitting hen. When the little chickens were hatched, I would fool these sitting hens. I would take these little chickens, and give them to another hen. I put them in a box with a lantern. Raise them on my own, get some more fresh eggs, mark them with a pencil, place them under the sitting hen, encourage the sitting hen and let them nest for another three weeks. I kept on fooling these sitting hens. When I look back on it, it was not the right thing to do. It was not the moral thing to do. It was not the democratic thing to do. It was not the most loving thing to do. It was not the most peaceful and non-violent thing to do. But I kept on cheating on these sitting hens. In America we have a large department store called Sears Roebuck. You can order everything. We used to think about ordering an incubator from the store, but we did not do it because we never had enough money. We called the catalogue the wish-book. I wish I had this, I wish I had that … So I just kept on cheating on these sitting hens.

As a young child growing up in rural Alabama, I wanted to be a minister. I wanted to preach the gospel, so with the help of my brothers, my sisters and my first cousins, we would sometimes gather all our chicken in the chicken yard, like you are gathered in this hall. My brothers, sisters and cousins were all lined up behind the chickens. They were the congregation and I would start preaching. When I look back on it, some of the chickens that I preached to in the 1940s and 1950s tended to bow their heads and shake their heads but they never quite said amen. But I am convinced that some of them listened to me, much more than some of my colleagues today in the Congress. As a matter of fact, some of those chickens were just a little more productive, at least they produce eggs.

I am so grateful to be here today because I am connecting with partners I have never seen in an on-going struggle that will continue long after we are all gone. There are three words that capture everything I will say to you today: The Struggle Continues. As you chart the course of peace movements around the world, you see the ups and downs, the highs and lows, and the wavelength of human dedication to the work of peace.

You see your work day-to-day as the work of research, as the development of a scientific record of the power of peace. I go to work day-to-day in a different society in another part of the world, in a time zone six hours behind yours. I am a congressman, a representative from Georgia, a player in the rough and tumble game of politics. While you are researching, I am voting. While you are writing, I may be speaking. While you are delivering a paper, I may be meeting with lobbyists or people from my district. But even though we are in different places at different times, in different societies, we are both engaged in one struggle.

And that struggle is not with the Republicans, with my fellow Democrats, with President Obama or with the Tea Party. Your struggle is not with the military, scientists or proponents of war in Iraq, Afghanistan, or the Middle East. You and I have a mission and a mandate, and its focus is not science or politics; its target is the human soul. We are engaged in an on-going struggle between the forces of light and the instruments of darkness finally meant to silence the inner conflict within the mind that gives rise to every battle, every wound, every difficulty we face in the world today.

You asked me to answer a question: What is the role of non-violence in the struggle for liberation? But in truth, this question has already been answered by greater men than I. Mohandas Gandhi put it this way: ‘It is either non-violence or non-existence.’ Martin Luther King Jr. put it another way: ‘We must learn to live together as brothers and sisters or we will perish as fools … There is no way to peace,’ they said. Peace is the way.’ Adherence to the path and the principles of non-violence is liberation. Our challenge is not to discover the truth, because our messengers have already come. They have told us what is true and even showed us with their lives.

They have sacrificed, given all they had to bear witness to this truth. Our struggle is not to find the truth, but to believe the truth. And once we have first convinced ourselves, then our struggle is to persuade the rest of the human family – who have their own minds, their own wills, their own destiny. We must show them that nonviolence is the more excellent way.

It was December 10, 1964, that Martin Luther King Jr. walked the streets of Oslo and accepted the Alfred Nobel Prize for Peace. It was 46 years ago when he said civilization and violence are the antithesis of each other. He said, ‘Sooner or later all the people of the world will have to discover a way to live together in peace, and thereby transform this pending cosmic elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood. If this is to be achieved,’ he said, ‘man must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love.’

You and I are brothers and sisters in a struggle. The struggle for peace is as old as the dawn of eternity. The seed was first planted in India, and the winds of change blew it across the ocean to be transplanted in the hearts and minds of ordinary people with extraordinary vision in the United States. We were not the learned or the elite. We were not the ones people hoped for or saw as blessed. We were those who many people hoped would disappear. We were those they tried to will into non-existence by denying us every civil right and every human right.

Many of us never had the opportunity to finish high school or even grade school. Attending the fine colleges just miles away from our own hometowns was like a distant dream. We were the ordinary people with extraordinary vision who got caught up in ideas espoused by men and women of the highest learning and spiritual prowess. The maids and the butlers, the farmers and the wash women heard the words of Martin Luther King Jr. which we study today. They followed the precepts of non-violent demonstration developed by Gandhi. They absorbed the messages of Howard Thurman, Jim Lawson, and Kelly Miller Smith.

Most of us did not have a PhD degree. Sometimes our subjects and verbs did not agree, but when we heard the truth, the truth that was written on our hearts, we saw it as a way out. We saw it as a road to our liberation. We decided to get involved in a struggle that would demonstrate non-violence is the better way. We did not have money, power or position. But we had ourselves, and we used what we had. We put our bodies on the line for the cause of civil rights and social justice.

When I grew up on that farm in rural Alabama my parents were sharecroppers. Sharecropping was part of a mean, cruel system of oppression painfully akin to the bondage of slavery that took over the South after President Lincoln emancipated the slaves at the end of the Civil War. As a young child, I tasted the bitter fruits of racism, and I didn’t like it. I saw those signs that said white men, colored men, white women, colored women, white waiting, colored waiting.

I used to ask my parents, my grandparents, and great grandparents. ‘Why segregation? Why racial discrimination.’ And they would say, ‘That’s the way it is. Don’t get in trouble. Don’t get in the way.’ But one day when I was only 15 years old, I heard the voice of Martin Luther King Jr., on an old radio. He was talking about Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He was talking about the ability of a committed, determined people to make a difference in our society. When I heard his voice, I felt like he was talking directly to me. I knew then that it was possible to strike a blow against legalized segregation and racial discrimination. I decided to get in trouble. I decided to get in the way. But it was good trouble. It was necessary trouble.

At 23, I was a young leader in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. I traveled around the country encouraging people to come to Mississippi to get involved with the Freedom Summer of 1964. At that time it was almost impossible for people of color living in the South to register to vote. In 1964, the state of Mississippi had a population of more than 450,000 blacks, but only 18,000 were registered to vote. In one county in Alabama – Lowndes County – 80% of the residents were African-American, and there was not one single African-American registered to vote. We were young people, but we began organizing in Mississippi with one simple mission: to register as many black voters as possible. It was a great task, but our passion for equality was even greater. We knew our mission would not be without risk.

In 1964, the state of Mississippi was a very dangerous place for those of us who believed that everyone should have the right to vote. And freedom did not come without a heavy cost. Less than a month after we arrived, three civil rights workers, three young men – Andy Goodman and Mickey Schwerner, both white and Jewish, and James Chaney, a black man – disappeared. Later we found out that these three young men had been arrested and taken to jail. That same night they were released from jail by the sheriff and turned over to the Klan. Then they were beaten, shot, and killed. I tell this story so you will know that the struggle for justice has not been straight, and it has not been easy. It has been a long, hard road, littered by the battered and broken bodies of countless men and women who paid the ultimate price for a precious right – the right to vote.

Just 47 years ago another generation had the courage, the capacity, and the ability to get in the way. They put aside the comfort of their own lives, and they got involved in the circumstances of others. Today, another generation took over the state house in the state of Wisconsin and is sitting in right now near Wall Street in New York. The pressure for an end to violence and the rule of tyrants world-wide is inextricably linked to the heritage of King and Gandhi because it is all a part of the same movement to ‘evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation’, as King said right here in 1964 in Oslo.

Day-to-day I struggle with my colleagues to find the way toward peace in our policy, and I struggle within myself at times to determine what is right in a sea of unsavory options within the political process at that moment. You struggle in the lecture hall, in front of the blank page, traveling to war-torn sites documenting the work of change, and debating the meaning of your findings with your colleagues. But in many ways all we are doing is holding a place.

We are holding the lamp of peace, shining our light in every quarter of our lives and struggling within our own selves to live by the concepts we seek to share with others. We are like trees planted by the rivers of waters whose roots grow and extend along the banks, and when the storms rage and the river overflows, our roots have the power to hold the soil in place. We keep the river banks from eroding altogether, from wearing away until there is nothing left. There will be setbacks. There will be problems that arise. And that is how I would describe the terror you experienced here in Norway in July 22. 77 dead, many more wounded. Innocent children and youth at a summer camp terrorized by the ranting and raving of a mad man, a professed Christian, a proponent of the extreme right wing, a man who left a bomb to explode right here in the fair city of Oslo, in a nation dedicated to peace.

Violence is never welcome on the pathway to peace. But as sojourners on this road, it is our work to decipher its meaning and to discover the way of peace in the most horrifying circumstances. In the tradition of Martin Luther King Jr. there is a saying that I would like to alter a little here. We say ‘all things can work together for good to those who love peace and are called according to its service.’ This is not to say that the work of violence is good. No. It is wrong to wage war, wrong to kill, wrong to spill the blood of innocent men, women and children, wrong to terrorize a peaceful city. But when it rears its ugly head, it demonstrates the distance we have come and the progress we have made.

It also demonstrates the work still left to be done. If we had believed that the end of World War II silenced the enemy. If we believed that our commitment to peace in the ivory towers of the university has encouraged the progress of humankind, these outbursts can serve us by demonstrating that there are powerful remnants of aggression still left in our society and in our world. Their vestments have changed, but they cloak themselves in the same robes as before. Yet somehow we have difficulty seeing them as the same seeds of hate with the potential to destroy.

During the last presidential election, I warned against the language of hate that sows seeds of destruction. So it was no accident that we experienced violence, racial epithets and even the wounding of a member of Congress soon after. Hostility can wear the robes of extremism, of religious fanaticism, self-righteous political parties or justified wars. It hides behind the law, like it did in the murder of Troy Anthony Davis by the state of Georgia, or it can be wrapped in national pride, like the rush to war in Iraq or Afghanistan. But hidden aggression will have its way.

There is no way to hide, to cover up, to justify, to rationalize, to alter the fact that until we adopt the ways of peace and reject the seduction of violence, we will reap a bitter harvest of destruction in our world. There is no way to peace, peace is the way. I have said many times on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives that war is bloody. War is messy. It tends not only to hide the truth, but to sacrifice the truth. And every war we have engaged in as a people has ended in the same way, with thousands, even millions of casualties. Thousands of acres of land are left barren and scarred. History is lost. Lives are torn apart. Men, women and children sacrificed for too little gain. These are not good stories. These are not the stories of America or Norway that we want to tell. But they are the stories of the 21st century that demonstrate the distance we have come and the progress we have made in this struggle.

In the Civil Rights Movement, we used to say ours is not a struggle for one day, one week or one year. Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, and each of us in our own sectors of the world, in our own professions, and in our own lives must do our part to build what we called the Beloved Community. ‘Consider those two words: Beloved Community. ‘Beloved’ means not hateful, not violent, not uncaring, not unkind. And ‘Community’ means not separated, not polarized, not locked in struggle.

The most pressing challenge in our society today is how we defend the dignity of humankind. Through our own inner revolution that moves our minds, our hearts and ultimately our world step-by-step away from the weapons of inner conflict, hatred against each other, through our demonstrated commitment to the principles we espouse we can build a society and a world community based on simple justice that values the dignity and the worth of every human being, what we like to call the Beloved Community, the Beloved World.

I would like to end with another story from my childhood; one that I think symbolizes the commitment we must make to the work of human evolution, to the work for peace. When I was growing up outside Troy, Alabama, 50 miles from Montgomery, I had an aunt by the name of Seneva. She lived in what we call a shotgun house. Here in Norway you probably don’t know what I am talking about. You have never seen a shotgun house. I was born in a shotgun house. It’s an old house, one way in, one way out. You could bounce a basketball through the front door, and it would go on through the backdoor.

My aunt Seneva did not have a manicured lawn. Just a simple plain dirt yard. And sometimes at night you could look up through the hole in the ceiling, through the holes in the tin roof, and count the stars. When it rained we got a bucket to catch the rainwater. From time to time she would walk out to the woods, and cut branches from a dogwood tree, and make a broom. She called that broom the breast-room. She swept the yard so clean, sometimes two or three times a week, but especially on a Friday or Saturday because she wanted that dirt yard to look good during the weekend.

One Saturday afternoon, a group of my brothers and sisters, and a few of my first cousins, about 15 of us young children were playing in her front yard. An unbelievable storm came up. The wind started blowing, the thunder started rolling and the lightning started flashing. And the rain started beating on the tin roof of this shotgun house. My aunt became terrified. She started crying. She thought the whole house was going to blow away. She got all of us children together and told us to hold hands. And we did as we were told. The wind continued to blow, the lightning continued to flash, the thunder continued to roll, and the rain continued to beat down on the tin roof of this shotgun house. My aunt cried and cried, and we cried and cried. One corner of this house seemed to be lifting from its foundation. My aunt had us walking to that corner to try to hold it down with our little bodies. When the other side appeared to be lifting she had us walk to that side to try to hold the house down with our little bodies. We were little children walking with the wind. But we never left the house.

My friends, the storms may come. The winds may blow. The thunder may roll. The lightning may flash. And the rain may beat down on this old house we call Oslo. Call it the House of Norway. Call it the House of England or France. Call it the American House. Call it the World House. We all live in the same house. We must never, ever leave that house. We must not give up, we must not give in, we must not give up.

During the last half of this century, we have come a great distance. We witnessed a non-violent revolution under the rule of law, revolution of values, a revolution of ideas, led by a man named King. But we still have a distance to go. As the great scholars, the great teachers, the excellent thinkers of this great institution, you still have the power to lead. You still have the power to change the social, economic, and political structures around you. We must build and not take down. We must bring together and not divide. We must lead and not kill. Love and not hate.

Because what Martin Luther King Jr. demonstrated decades ago and what Gandhi showed us before that is still true. It is eternally true. ‘Unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word’ in our world. That is why ‘right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant.’ You still have the power to lead a non-violent revolution of values and ideas in not only Norway, but around the globe. If you use that power, if you continue to pursue a standard of excellence in your daily lives, then a new and better world – a Beloved Community – begins with you. So I say to you: Walk with the wind. And let the spirit of peace and the way of non-violent action be your guide.

Thank you.

See comments to John Lewis’ PRIO Annual Peace Address 2011 by Kathleen Cunningham and Henrik Syse:

- Kathleen Cunningham: Non-violent Struggles: Scholarship, Policy and Realities

- Henrik Syse: Leading a Charge Against Injustice