Illustration: Espen Friberg / Morgenbladet

‘Calculations made by a former president of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, with the assistance of historians from a number of countries, show that since 3600 BC, the world has known only 292 years of peace. Since 650 BC, there have been 1,656 arms races. Sixteen of them ended in economic collapse, the rest in war.’

This story, or slight variations of it, has been circulating in the media for well over 60 years. Military periodicals, in both East and West, as well as journals published by the peace movement, have taken this story at face value.

This is despite the fact that the original author, Norman Cousins, in the heading of his article, which was published in St Louis Post-Dispatch, referred to an ’imaginary experiment’ and later referred to the story as ’fanciful’. The figure for the number of years of global peace seems to have been taken from some rather vague suppositions advanced by European historians in the second half of the 19th century, while the statistic regarding arms races that end in war was a pure invention by Cousins – as was the role of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. In Cousins’s first article, he safeguarded his position by giving the Norwegian author the name ’Dr. Storhjerne’ (‘Dr. Brainy’).

Nonetheless, this tale migrated from the world of fantasy literature into popular non-fiction on the subject of war and peace. Although the origins of this story have been revealed a number of times, the first time as early as 1962, it has proved a difficult story to eradicate. The most recent reference I have found to the story was in a textbook on the causes of war published in 2013 by a well-reputed American academic publishing house. In this case, however, it was presented with a certain amount of scepticism.

Serious research has been conducted on both the relative numbers of years of war and peace, and the link between arms races and war, and I have no wish to distance myself from the warning about arms races that Cousins wished to convey. The problem is that there is no link between this serious research and the popular story that has been circulating for two generations.

It is perhaps the most resilient myth about war and peace in our times.

But there are many others. Here are six more.

More civilian than military victims

‘In the old days, 90% of the victims of war were military and only 10% were civilians. Today it is the other way around. War is becoming more and more destructive for civilian populations’.

There is no scholarly basis for these figures. There is nothing new about war being very harmful to civilians as well as to military personnel. Some innovations in warfare (weapons of mass destruction, carpet bombing) obviously put civilians at greater risk. Meanwhile other innovations (precision weapons, civil defence) have the opposite effect. It is impossible to confirm where these figures come from, even though it is possible to identify some of the publications that are primarily responsible for having disseminated them so widely.

The war in Congo was the biggest since World War II

‘The war in Congo (the DRC) in the late 1990s had 5.4 million victims and was the biggest war since World War II’.

This figure does not derive from any statistic concerning the victims of the war, but from a comparison of mortality rates before, during and after the war. This study was based on an estimate of mortality rates before the war that was far too low, which naturally led to a corresponding over-estimation of the increased mortality rates due to the war. Many people who have used this figure have also made the mistake of comparing the figure for all deaths as a result of the war in the DRC (that is, battle-related deaths as well as deaths resulting from illness, hunger and poverty in the wake of the war) with estimates for purely battle-related deaths in the two bloodiest wars since World War II: Korea and Vietnam. But these wars also caused very many indirect deaths and almost certainly took more human lives in total than the war in the DRC.

Three out of four women were raped in Liberia

‘75% of women in Liberia were raped during the civil wars in the 1990s’.

Most of us have not heard anything for a while about this brutal civil war, although many of us will have heard about these numerous rapes. This claim was repeated most recently – and went unchallenged – in a report published in the middle of last month by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. The report quotes a survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), which found that 77.4% of women in Liberia had been raped and that 64.1% of these women had been the victim of multiple rapes. But no one should be fooled by the apparent precision of these figures, since the WHO’s survey only included victims of sexual violence. In other words, the survey is in no way representative of Liberian women in general. Once again we see that a serious problem, namely sexual abuse during war, is increasingly the object for serious research, but that this research is overshadowed in the news media by myths.

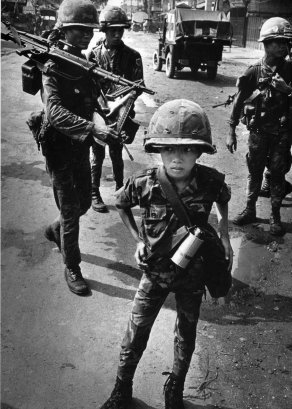

Child soldiers are not a new phenomenon – Ten year old South Vietnamese soldier in 1968. Photo: Philip Jones Griffith

200,000 child soldiers

‘There are 200,000 child solders fighting in wars around the world’.

Figures of this kind were disseminated by a number of humanitarian organizations almost a decade ago. But this figure lacks any scholarly basis. It is most likely far too high, but no one has a reliable global estimate. The use of child soldiers in many conflicts is a deeply worrying phenomenon. But child soldiers are not a new phenomenon of recent decades. We find them as early as the war between Sparta and Athens in the 5th century BC.

Modern wars take a greater number of lives

‘Modern wars are becoming ever more brutal and taking greater numbers of lives’.

In absolute figures, the first half of the 20th century represents a perverse ‘high point’ for the ability of humans to kill each other in war. And just a decade later, China set a similar record for what is now often referred to as one-sided violence (violence against civilians who are not participating in any organized uprising) when some 45 million people died in ’the Great Leap Forward’ with the collectivization of agriculture and forced industrialization. But since World War II, the numbers of people killed in inter-state and civil wars has fallen dramatically. And the same is true of statistics for one-sided violence since 1960. This fall becomes even more dramatic if we look at these figures in light of the strong population growth in these decades and focus on the likelihood of any random person being killed in war or by one-sided violence.

Civilization led to war

‘Before the advent of civilization, people lived together in peace’.

We find this Rousseau-inspired idea about ’the noble savage’ in, for example, a scholarly article dating from 1965 by two Norwegian peace researchers. The idea also thrives in popular literature. But the societies that we referred to as “primitive” only a few decades ago, had on average far higher rates of violent deaths than our society, even though there is continuing scholarly debate as to how many of these deaths should be counted as homicides and how many as war-related. A summary by the archaeologist Lawrence Keeley found that on average 0.5% of the population in a society without an organized form of government would die violently each year – this is more than 10 times the number of people who die in our own times as the result of war, civil war, one-sided violence, homicide, suicide, and road accidents.

Do these myths have anything in common?

They express a widespread pessimism that everything is going to hell in a hand-basket, and perhaps also represent a modern form of self-flagellation – everything is our own fault! In truth, modern civilization creates many problems, but we will not make any further progress by exaggerating these problems or by ignoring the progress we have already made.

- Nils Petter Gleditsch is a research professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and is also professor emeritus of political science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU). His book Mot en mer fredelig verden? [Towards a more peaceful world?] was launched last week by the Norwegian publisher Pax Forlag. This book discusses several of these myths in greater detail.

- This text was published in Norwegian at the science news website forskning.no 11 November 2016: ‘Myter om krig og vold‘

- Translation from Norwegian: Fidotext