As we discuss the relationship between public and private mourning and grief, consider the emotional handling of the Newtown school shooting in 2012, where twenty children were killed at Sandy Hook elementary school.

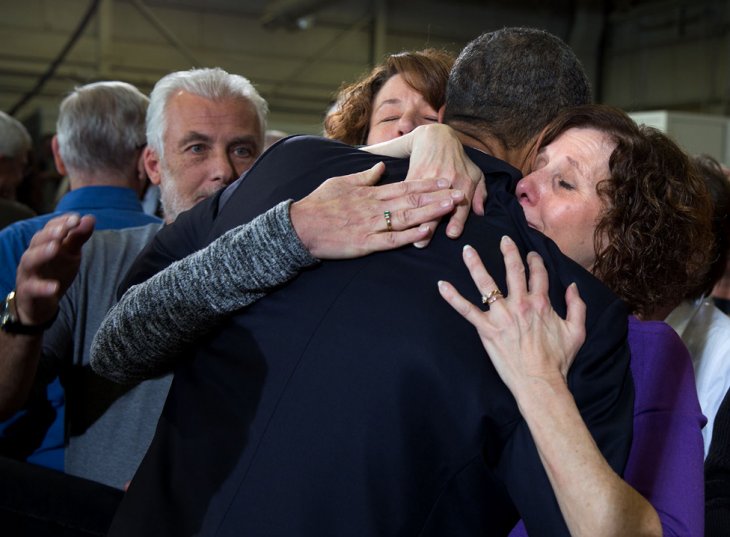

Such a traumatic event destabilizes people, creating a felt deficit in emotional support. When President Obama visited the community, his role was clear: he needed to voice strongly the entire nation’s support for the affected community.

President Obama with women who lost family in the School shootings in Newtown. Official White House Photo by Pete Souza

Newspapers reported factually on the visit, quoting parts of the speech, but leaving it up to the reader to respond emotionally. Television, by contrast, revealed itself to be a far more potent medium for evoking emotions.

First of all, an emotion can be named and categorized in familiar ways in language, yet the mere naming of an emotion is not an effective vector for spreading it.

Emotions are contagious, but this contagion is dependent on a complex series of multimodal cues: the rhythm of the speech, not to mention the significant pauses and interruptions; the hand moving up to the corner of the eye to dry a tear, the sorrowful face. These expressions of emotion communicate directly and contagiously, along channels of communication that run parallel to, yet autonomously from the linguistic message reported in the newspapers. They perform a kind of work directly and forcefully, communicating a comforting, yet vaguely specified set of intentions that are received as reassuring.

Emotions can be understood as incipient actions: they signal in somewhat general and unspecified terms what you are inclined to do next, whether that is an act of aggression or kindness, solidarity or hostility. When the President, or the King, publicly performs grief, this is intended to signal to the victims that the nation stands with them in solidarity. This in turn carries the tacit implication that they will receive resources to help them cope, yet this implied message need not be explicitly spelled out: the mere emotion, if genuine, carries the assurance that help will be forthcoming, and that tacit promise is reassuring precisely in being unspecified, communicating an unqualified concern.

The fact that the leader of the country publicly performs grief also signals to everyone else that this grief is normative, that the leader is speaking on behalf of everyone and thereby is establishing an emotional imperative: this is how we respond to this crisis.

Television is uniquely suited to carry these non-verbal messages, and thus facilitates what Odin Lysaker refers to as the “affective turn” in politics. There is no lexical substitute for direct emotional communication. For commercial television, such events fall straight to the bottom line, drawing in viewers and increasing advertising revenues. US networks devoted significant amounts of airtime echoing the President’s performance after Newtown, displaying themselves in the act of performing grief in sympathy with the President, and reflecting on the events. In this way, the mediatization of grief is pulled into a commercial frame. Here, the collective descent into a normative emotion takes on the flavor of entertainment, a set of feelings that are harmless, safe and deprived of any practical consequences, serving no purpose but to hold people’s attention until the next commercial.

While television excels in conveying the significant multimodal dimensions of communication and social relations, it is equally capable of subverting the political function of emotion to its own imperatives, turning politics into theater.

- This text is also published in the NECORE newsletter marking the sixth anniversary of the terror attacks in Norway 22 July 2011. Read more from the newsletter by following this link.