Photo: Right Livelihood Award 2012

Gene Sharp – a pioneer in the study of non-violent action – died peacefully at the age of 90 on 28 January 2018. Obituaries in many newspapers have highlighted his contributions to the study of non-violent resistance against dictatorial regimes, pointing to how his work inspired the Arab Spring and his reputation as a “dictator’s worst nightmare”.

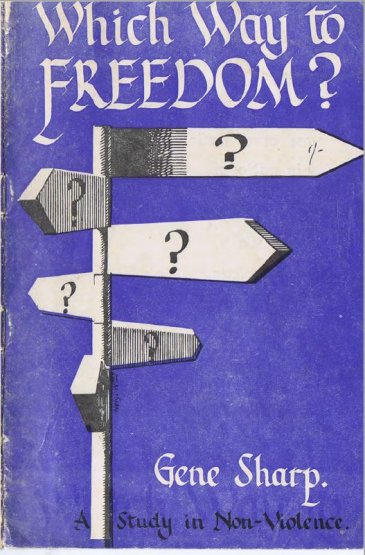

However, there has been less attention to other sides of Sharp’s work and other important forms of non-violent action. Indeed, Sharp’s first 1957 published pamphlet Which Way to Freedom? was written for the Welsh Nationalist Party Plaid Cymru, and argued for non-violence as a more effective way for national liberation than violence.

Although separatism and nationalism is often associated with violence and terrorism, especially when the state tries to restrict the political space for separatist or nationalist claims, the recent rogue independence referendum in Catalonia attests to the enduring relevance of forms of direct action and civil disobedience such as illegal protests in nationalist campaigns.

Although separatism and nationalism is often associated with violence and terrorism, especially when the state tries to restrict the political space for separatist or nationalist claims, the recent rogue independence referendum in Catalonia attests to the enduring relevance of forms of direct action and civil disobedience such as illegal protests in nationalist campaigns.

On p. 17, Which Way to Freedom? lists as one of the demands of Plaid Cymru “a Welsh Parliament with freedom within the Commonwealth, sitting at Cardiff, the Capital”. This aim was achieved 30 years after the publication of the pamphlet when the devolved National Assembly for Wales was set up in 1998, following a 1997 referendum.

To what extent did non-violence contribute to the Welsh Assembly? How perceptive was Sharp’s pamphlet in outlining a non-violent strategy for independence?

Which Way to Freedom? is very much rooted in the idea of national liberation from colonialization or foreign occupation. Sharp is sympathetic to the case for Welsh independence, and the need for national liberation to use extra-legal methods and reject gradual reform. However, he argues that violence is not necessary for revolution, and indeed that it is typically counterproductive.

A standard argument for the need for violence is that colonizers or occupiers are likely to rely on violent repression. Sharp highlights how not responding in kind with violence has important “psychological effects” (p. 14), including generating international support for the cause of the non-violent nation and a “chance of support of sympathy and even active support from nationals of the invading State”. A movement that does not rely on arms is also less likely to be vulnerable to decapitation, when leaders are removed, or the loss of arms.

One of the things that Sharp may have underestimated is how unconventional political activity often becomes influential precisely through its impact on the evolution of conventional politics. In India, outside reactions to British repression against the calls for independence, especially by the USA, appear to have influenced the authorities to agree to independence. Welsh nationalism has not figured prominently at the international level, but the final success of Welsh autonomy very much came about through winning over other British national parties rather than just building a separate pro-independence movement. In particular, the Labour Party eventually adopted a pro-devolution position in the 1970s. The main opposition resided with the Conservative Party, who gradually lost influence as their local representation started to dwindle. Although other national minorities in Europe such as the Corsicans also gained greater autonomy despite violent campaigns, nationalist violence would likely have strengthened resistance to devolution.

The Spanish government’s recent reaction to the Catalan independence movement seems like a textbook case for how not to respond to separatism and the greater challenges posed by non-violent separatist movements. Arresting Catalan nationalist leaders for “illegal rebellion” and responding to the referendum with police and force has failed to stem nationalist support, although the population of Catalonia remains divided over the merits of independence. The commitment to non-violence by Catalan independence has helped generate international condemnation over the disproportionate Spanish use of force. Catalan nationalists may not achieve their aim of full independence, but the Spanish reaction appears to have made it more likely that we will see greater devolved fiscal autonomy, similar to the proposals Rajoy previously rejected.

Recent research suggests that non-violence has been a more effective strategy for self-determination groups than violence. Moreover, ethnic powersharing and devolution is becoming more common, in part because people come to appreciate the success of previous cases and overcome resistance. This suggests that Sharp’s intuition was generally right, even if we still have much to learn about the causal mechanisms.

- Kristian Skrede Gleditsch is Regius Professor of Political Science, University of Essex and Research Associate, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

The arrest of separatists leaders was on the premises of acting against the national democratic constitution, declaring, unilaterally, an independent republic. Also the security forces were provoked but no major injuries were reported by local hospitals. Therefore, in what context do we place violence?

Many thanks for your comment.

Sharp explicitly defends civil disobedience for separatists movements, and I think there are many cases where formally illegal acts can be justified in political campaigns. We often see divergences between prevailing laws and social norms/values – homosexuality was banned in many democratic countries up to the 1960s/1970s, but is now often replaced by bans on discrimination against gays and lesbians.

My aim here is not to take a position on the relative authority of Spanish national institutions vs Catalan institutions, but what Sharp said about the consequences of non-violent separatist campaigns and government responses. The Spanish response in my view used excessive force in the sense of going to too great lengths to try to stop the referendum, even if not necessarily causing many injuries, and I think it was ultimately counterproductive.

[…] 16.- From Wales to Catalonia and Beyond: Gene Sharp and Non-Violent Nationalism, February 6, 2018 by Kristian Skrede Gleditsch & filed under Peace Research,https://blogs.prio.org/2018/02/from-wales-to-catalonia-and-beyond-gene-sharp-and-non-violent-nationa… […]

[…] https://blogs.prio.org/2018/02/from-wales-to-catalonia-and-beyond-gene-sharp-and-non-violent-nationa… […]