Pavel Baev in 2008. Photo: Lise Åserud / NTB scanpix

Pavel Baev, interviewed by Stein Tønnesson

In the late 1980s, when I took part in drafting speeches for Mikhail Gorbachev underpinning his concept of an ‘All-European House’, one part of my work was to strive towards the elimination of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Nothing came out of it at the time. Now, after more than 25 years at PRIO and having become a Norwegian citizen, the same question has taken on a new complexity with the worsening of East-West relations. I want to return to the work I did at the time, and co-operate with my PRIO colleagues on a project aimed to reduce the not negligible risk of a limited nuclear war in Europe.

Growing up in a Soviet Happy Peace

Stein Tønnesson: Pavel, you were born in 1957, the year of the Sputnik. How was it to grow up in the Soviet Union during the Cold War?

Pavel Baev: As you say, I was born in the year that Sputnik was launched, which means I’m two years older than PRIO. Nothing in my childhood, my teens, or my twenties prepared me for the huge change in my life it represented to become a PRIOite.

I had a very stable childhood. In my early years, the Soviet Union was very much on track. Going to school was a regular thing and the quality of our education was satisfactory. We had a fair chance to continue studying, and I was lucky enough to be admitted to Moscow State University. Only one out of twenty applicants were admitted, so the competition was tough indeed. I prepared myself seriously for this big advance in my life, and I felt privileged in many ways as a student in the best of all the universities in the Soviet Union.

Could you tell me about your parents? I assume they must have lived through the Great Fatherland War and the whole Stalin period?

Yes, certainly. The war had a huge presence in the lives of my parents, though they were not old enough to actually fight. That was my grandfathers’ plight. Both my grandfathers fought in the war and were lucky to return home.

For my father, the war came very near. He lived in Moscow and experienced the shock of evacuation, when Hitler’s troops came close, but the family returned after Moscow was saved by the Soviet forces. My mother, however, had a summer break in 1941, just before the German onslaught, in her native village in the Smolensk region, and was cut off from Soviet-controlled territory when the territory was captured by German troops. Her village was liberated only in 1944. For a long time, my grandmother and her two daughters had no contact with my grandfather who was at the front and both had to presume the worst, which fortunately never happened. So, my family certainly has its war memories.

I myself, however, belong to a generation for whom war was already a distant occurrence, something we had just heard about. The two world wars and the October Revolution and everything that had happened in the first half of the 20th century was already a matter for the history books. Life around us had very little connection with war. I lived in a stable and, in many ways, peaceful period – not particularly tense. I had a feeling that everything was on track and I knew more or less what I might possibly achieve in life. It might be a little bit better or a little bit worse, but everything was very much predetermined – even a little boring. For a teenager looking for adventure, for conquering new horizons, my only conceivable battlefield was in the competition for a good university exam.

At what age did you join Moscow State University and how did you get in?

I still cannot believe my good fortune. I was admitted immediately after finishing my ten years of schooling, and was only seventeen when I entered. I spent five years in the university, which was normal in the Soviet Union back then. In fact, across all disciplines the basic higher education had a five-year duration. I had been fairly young when I graduated from secondary school and seized my chance to get a college education. At my school, nobody else in my year of graduation tried to get into a top college, though many of my friends would receive a higher technical education.

I chose geography as my subject. My heart was more in history, but the history department was full of ideology. Marxism-Leninism dominated every part of the curriculum, even antiquity. Geography was basically free of ideology, and we could choose from a range of topics, from meteorology to the economic structure of foreign countries, which was already my specialty.

Moscow State University. Photo: Alexey Kljatov / Wikimedia Commons

You talk as if this were a happy period in your life.

Of course! I was suddenly in a place where I felt free, with new horizons opening and many interesting friends. I experienced my first love, could go on summer expeditions to different corners of Russia, and even abroad. My first foreign trip went to the German Democratic Republic, where I first saw the Berlin wall. And back in Moscow, when looking out of the window in the reading room of the high university skyscraper in the Leninskie Gory, I could see the global metropole of Moscow below me, a lot of sky above, and freedom all around. It was a very happy time.

So, you had a stable childhood in the age of Nikita Khrushchev and entered university in Leonid Brezhnev’s time. What is your view today of those two Soviet leaders?

Khrushchev had to step down when I was still just a boy, in my first class at school. We were given textbooks with a big portrait of him and were ordered to remove that page from the book. So, my only memory of Khrushchev is his removal. My time in the Soviet Union was the long, long Brezhnev era. It seemed incredibly long, and it was quite a surprise for me to recently realize that Vladimir Putin has now held power longer than Brezhnev.

The beginning of the Brezhnev era was full of hope, full of expectations. There was a feeling that the Soviet Union – the whole of this huge multi-ethnic country – was on track. There had been big problems in the past, not just with the war but also with internal repression, but now everything was getting better and life was improving year by year.

This was the perception I had during my school years and at university. It seemed that there would be many interesting opportunities ahead, and there was no prospect of any dramatic change. The country would stay on track and no major breaks or breakdowns could possibly happen. This proved of course to be an awfully wrong impression, but this is something I can only say with hindsight.

The beginning of the Brezhnev era was full of hope, full of expectations. There was a feeling that the Soviet Union – the whole of this huge multi-ethnic country – was on track. […] This proved of course to be an awfully wrong impression, but this is something I can only say with hindsight.

By the time you finished your studies in 1979, I assume you had not made other foreign trips than the one to East Germany?

I also took part in a student exchange with Bulgaria during a short winter holiday, and I had travelled to Yemen as a schoolboy already. My father worked in military intelligence, so he took my mother and my little brother with him to his assignments abroad: first in northern Yemen, and later Egypt. I did not make it to Egypt, but I visited my family in Yemen.

Joining the Soviet Military?

So, you had international experience from early on. And when you had finished your studies, the first job you got was for the military, wasn’t it?

Yes indeed. I was assigned to a military research institute affiliated with the Soviet Ministry of Defence, doing a lot of hard research on the potential enemy. My specialty was the United States – the various aspects of its military policies.

To get that job was a huge change in my life. Suddenly, after all the openness and freedom I had enjoyed at the university, where so many roads seemed open, I found myself confined to a restricted and controlled environment with bars on the windows, and no opportunity to travel abroad. The discipline was rigid. All my superiors were military officers, and for them such discipline was natural. They felt that it was more relaxed in the ministry than in the military units they had served in before. For me, it was incredibly tough.

Did you think of choosing a military career – putting on a uniform and perhaps one day becoming a Soviet general?

Of course. I was invited several times to join. Though probably I would never have made it to the level of a general, since I came in from the side-line with no basic military education. I would always have been a second-rate officer, with limited prospects. Yet a life in uniform would have been financially beneficial. I could have doubled my salary. But for some reason, I never felt it would be right. So, I resisted the persistent invitations.

Sometimes you make choices in life that you can’t quite rationalize in hindsight. During my second year at PRIO, for instance, when I was on a temporary contract, the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) announced positions in its newly created Centre for Russian Studies. These were secure, well-paid jobs. Some of the guys who got those positions are still there, like Jakub M. Godzimirski and Helge Blakkisrud. I did not apply. While it was my field of study, I felt myself a part of the PRIO family, so to apply from PRIO to NUPI just did not feel right. I never applied and never regretted that I didn’t.

So, by instinct you shied away from NUPI and the Soviet military. Yet you worked as a civilian for the Soviet Ministry of Defence at a time when the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan and the Cold War in Europe got colder.

That’s right. I joined the Ministry of Defence in September 1979, and in December the Afghan War began. Several of my colleagues disappeared from our corridors when they were sent south. This remained a pattern during all my years there. Some of them never came back because they were reassigned to other jobs, and some came back as very altered people, I would say. One was killed. I went with a group of colleagues to the military airport to receive the heavy coffin. That certainly made an impression. War had come into my life. The whole atmosphere changed dramatically in those years, from the hopes created by Razryadka (Détente) to a new phase of confrontation with a real threat of an east-west war. My colleagues indeed saw it coming.

Trying to Build a European House

But then came Mikhail Gorbachev.

Indeed. Which, even in hindsight, seems like a miracle. A lot of things changed for the better: in the world, in the Soviet Union, and in my life. Once Gorbachev had pronounced the words, “All-European House,” a new think-tank was created to develop that concept. This became the Institute of Europe in the Soviet Academy of Sciences. I joined that Institute at its creation in 1987.

Two years after Gorbachev had become General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, you joined a new think-tank to study his idea of an All-European House.

Yes, this was a time of incredible change. After a period when general secretaries came and went (Yuri Andropov, Konstantin Chernenko) and nothing changed, suddenly with Gorbachev the wind of change began to blow. And again, one of its manifestations in foreign policy was the idea that Europe is our common house. We felt a need to put the confrontation and the risk of war behind us. We wanted to adjust our minds to the fact that we live together in this house and must be good neighbours.

Did you meet him?

Several times, but never privately and never one to one.

Did he read your stuff?

Yes, but most of our texts were collective. We wrote drafts for his speeches and for papers to be circulated to the Central Committee of the Communist Party. So, our think-tank was heavily involved in foreign policy making. We produced new ideas in abundance for Gorbachev and Eduard Shevardnadze, who was Soviet foreign minister at the time. [Four years after the Soviet Union’s demise, he became President of Georgia, serving from 1995–2003].

When you worked for the military you were an expert on the United States, but now you focused on Europe.

My main area was arms control and the possibility of a new military détente, and our relationship with the United States was crucial. Even though Gorbachev aimed for an All-European House, the United States could not but be considered an essential part of the balance-of-force and the security structure that were needed to make it happen.

First meeting of President Reagan with Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

One part of my work concerned the role of nuclear weapons in Europe – non-strategic nuclear weapons, which were mostly American. We prepared ideas for possible negotiations. Nothing came out of this at the time, so now, at the ultimate stage of my research career, I want to return to this unresolved problem, which has acquired a new complexity. Together with some of my PRIO colleagues, like Greg Reichberg and Louise Olsson – and possibly Stein Tønnesson if he has any free capacity – we might give a new push to that problem, which is a leftover from the final phase of the Cold War, but has acquired a new quality in the current situation.

That could be useful indeed. When you worked for Gorbachev’s new institute, did you then again have a chance to travel abroad?

Seeing the Wall Come Down

Yes, a year and a half after I joined the Europe Institute, my security clearance expired, and I was clean to go. I travelled to several countries, mainly in eastern Europe. A trip to Poland produced a particularly strong impression because it gave the Perestroika [Gorbachev’s slogan for reform] a new meaning for me. Poland went for deep reforms, some of them painful with a lot of inflation, yet with new, intense hope.

In the following year, 1989, one of the strongest impressions I have had in my whole life came during a conference I attended in East Berlin, organized together with the GDR think-tank EPV. We held Soviet-German talks about European security just as the Berlin wall came tumbling down.

EPV?

I do not recall what the abbreviation stood for … it soon disappeared together with the whole GDR state.

Crowds throng around the Brandenburg Gate following the structure’s official opening on December 22nd, 1989. Photo: SSGT F. Lee Corkran / Wikimedia Commons

Were you actually there at the moment when it fell?

Yes, the venue of our conference was a little outside Berlin. Around it was a big park, in which everything was peaceful and quiet. But in the evening, we could go to Alexanderplatz and hear the colossal crowds chanting “Wir sind ein Volk!” In the morning, we went back and were surprised to see that everything had returned to peace and quiet. Not a single glass had been broken, and everyone seemed to be back at work. This very quiet morning was followed by a colossal explosion of emotions in the evening. On the last day of our conference, the wall was torn apart – brick by brick.

What were your emotions at the sight?

It was a shock, an unintended result of our new foreign policy. We lost control of the All-European House we were trying to build, and saw all our brilliant ideas about how to manage the rapprochement between east and west go overboard. Suddenly the process gained a momentum of its own. The new European dynamics were no longer manageable.

What did you feel about Gorbachev then, and how do you assess him now?

What happened in Berlin was something he had not foreseen. As leader of the Soviet Union, he thought that he would be firmly in control of events. He expected his decisions and his guidance to determine Europe’s future. Then, suddenly, the events took on their own momentum.

After that, he was lost. His last two years were a period of indecision. He was unable to regain control, unable to understand what was happening. Inside the Soviet Union, he was no longer obeyed or taken seriously.

The First Norwegian Encounters

In 1989, when you were thirty-two, had you already heard about PRIO?

No. My acquaintance with PRIO started in the following year, when I met Sverre Lodgaard at a conference. I don’t remember where. There were many conferences at the time, and I met several Norwegians before him, including Johan Jørgen Holst [NUPI director 1981–86 and 1990–91, Minister of Defence 1986–-89, 1990–93, Minister of Foreign Affairs 1993–94], who took part in our programme on non-strategic nuclear weapons. He participated in several workshops and impressed me with his work capacity. He took an energetic part in the discussions, generated new ideas and discussed other people’s proposals. He was never one to just present his own paper.

So, Sverre Lodgaard, who was PRIO director at the time, met you somewhere in the All-European House?

Yes. In one of the conferences around Europe. He invited me to come to PRIO for a week, and that week happened to be in January 1991. I came to PRIO with some of my prepared ideas…

Was this your first visit to Norway?

Yes, but I had already met several Norwegians. One of them was the leader of the Conservative Party, Kaci Kullmann Five (1951¬–2017). I met her in Moscow at a reception in the Norwegian embassy. She introduced herself as just Kaci and impressed me very much. She was sharp and keenly interested in what was going on. She did not conform to my idea of what a conservative party leader was like. I was so impressed that I have voted Høyre ever since.

What was your first impression of PRIO? How were you received when you arrived in Fuglehauggata 11, where I was struggling to finish my doctoral thesis at the time when you arrived?

The visit did not take place in a convivial atmosphere, because it coincided with King Olav V’s death and the First Gulf War. My seminar presentations were overshadowed by these events. Nevertheless, I felt I had come to a friendly place, open to interesting discussions. So, I returned the following year for the launch of Security Dialogue. Magne Barth, the editor, invited me to be one of his associate editors. Then, in February–March 1992, I came for a full month.

Magne Barth had taken over from Marek Thee as editor of the Bulletin of Peace Proposals, which was relaunched under the name Security Dialogue. It celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year, counting all the years of both the BBP and Security Dialogue. And you were involved in the relaunch.

Yes, I was present at the conference where we brainstormed about the launch, decided on the new name, developed a design, established a list of possible contributors. For me, this was hugely interesting. I felt that I was part of a big transformation in international affairs.

The Demise of the USSR

By the time you came back for your second visit, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was gone. How did you experience that?

Well … it was a new shock. Not so much the collapse, but the military coup that failed. I witnessed it first-hand, because our institute was located in central Moscow. I came to work on a Monday morning, and there were tanks all around. I stood with my father that crucial night outside the Moscow White House. We stayed the whole miserable night under drizzling rain, expecting any moment that the storm would come – and then suddenly in the morning, miraculously, there was victory! The troops withdrew. Gorbachev returned from his captivity in the Crimea and the nightmare disappeared. But again, from that moment, the Soviet Union was seriously broken. Its dismantlement and collapse soon followed.

This was Boris Yeltsin’s victory.

Yes, it was. He was there, standing on top of a tank in front of the White House. I saw him. It was his moment in history, and he did not chicken out. With all his weaknesses, all his later controversial decisions, and his Soviet past hanging heavily on him, this was his historical opportunity, and he did not miss it.

How did the shift from the Soviet Union ruled by Gorbachev to a Russia ruled by Yeltsin affect you personally?

It was a big change. Gorbachev was – with all his weaknesses, all his helplessness in the last few years – in my view a better leader than Yeltsin. Not least because Gorbachev was always attentive to expert advice. He invited different opinions and made up his mind after serious consideration. Yeltsin was impulsive and did not trust any of Gorbachev’s advisors.

So, our think-tank lost its relevance for policy making. Our connection with the government was broken. It was unclear how Russian foreign policy would be managed. At the same time, due to hyper-inflation, our salaries were so small that it was difficult to survive with a family. So, when Sverre invited me to come to PRIO for half a year, maybe a whole year, I saw it as a fantastic opportunity.

Would you have accepted that invitation if Gorbachev’s Soviet Union had survived?

That is a hypothetical question. It depends on how Gorbachev had behaved. At the middle of his reign, we had a feeling of being involved in something profoundly important, making a difference in such a way that even a short trip abroad was difficult to manage because we might be missing something very important. But then he lost touch…

Do you think Gorbachev deserved the Nobel Peace Prize?

Yes, very much so. His first response was surprise: what does this really mean? We managed to explain to him that it was a great achievement and honour. In the Soviet Union, the reputation of the Nobel Prizes had been damaged by some problematic decisions related to literature. The prize to Boris Pasternak left a strong aftertaste. So, it took a few months for Gorbachev to understand the significance of the peace prize. Now, if he looks back, he probably sees it as a very important moment in his career.

So, in 1992, Pavel Baev comes to Fuglehauggata 11 for a period of half a year. You go to work in Oslo every day. You learn how to use a punching card. Did you bring your family?

Yes, we arrived together as a small family of two, and a few months later we became a small family of three. In fact, that was a strong incentive to come to Norway, since in Moscow at the time it was logistically and medically difficult to give birth. The only thing that worried me – and I asked Magne [Barth] about it during one of our conversations – was the price. How much would it cost me in Norway? And Magne looked it up, and told me that immediately after giving birth, my wife Olga would be paid an amount of money, and then she would receive the same amount of money every month. For us, this appeared absolutely unthinkable and incomprehensible, and made the decision to come and to stay even easier.

When and how had you met Olga, and when did she become Olga Baeva?

We were in the Institute of Europe together from the beginning when it was a small think-tank with about a dozen people. She was personal assistant to the deputy director, and I was the head of one of the departments. It is one of those incredible treasures in life that we would work in the same institute in Moscow, and end up working in the same institute in Oslo.

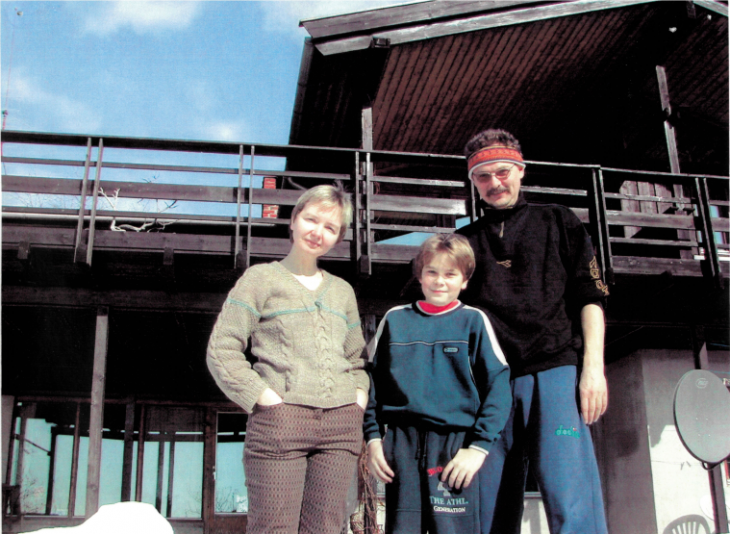

Pavel Baev and his wife and fellow PRIOite, Olga Baeva, along with their son, Fyodor in approx. 2000. Photo: Private archives

Yes, she is the head librarian at PRIO now. And so, already in 1992, when you were here for your first long stay, Fyodor was born.

We arrived in mid-October, and he was born in late January. That was the most important event in our lives, and much of my further effort at PRIO was driven and determined by the fact that we were three and I was a responsible father, and that it would be have been difficult to manage the family economy in Moscow. This opportunity was simply too important for us all to miss.

It must have been a big move for a family with a pregnant wife to move to a foreign country, not very far away but still foreign and belonging to a different world during the Cold War. How was it to settle down in Oslo for a Russian family, and did you get adequate support from PRIO?

Oh yes, oh yes. Absolutely and without doubt. When we arrived, my first impression was that PRIO had become a smaller institute. Sverre was no longer there. Several others had left as well. All in all, there were probably about two dozen people on PRIO’s payroll. All of them were so friendly and supportive, helping us with finding an apartment and explaining how the system worked.

For us, PRIO was really our main support system, because we had nobody else in this country. But still, in Moscow back then, many things were so hard and so impossible to buy with any sort of money, which we also did not have anyway, so, Oslo felt like a blessing.

A Changed Moscow

Here in your office, you have a big map of Moscow on the wall. Do you sometimes miss the city where you grew up?

Yes, I miss the Moscow that is no longer there. I miss my mother and my brother, who still live in Moscow. Moscow is a very hard environment. I probably cannot imagine myself going back.

Each time I visit, the stress and noise, pollution and tension are so acute that my system, which is spoiled completely by Norway’s clean air and water and regular life, starts to fall apart already after a few days.

So, the Moscow you knew was destroyed in the age of Yeltsin?

Not exactly destroyed. It evolved into a different place – hugely interesting, by the way! It is very dynamic. It is very hard driven. The speed of life there is incredible. It is hard to compare it to anything else. Even in China, where you and I have been travelling together, even in New York, the speed is slower. Moscow is now a hard place, tense, where you have to elbow your way in crowds. It is very competitive, and the competition is not nice and fair.

A Young Female Director

When you settled down with Olga and Fyodor in Oslo, was it already your intention to try to prolong your contract and stay?

My intention was to prolong the half-year stay to a year-long stay. This was the first task I set upon when arriving. Hilde was the acting director…

Hilde Henriksen Waage was acting director, and Sverre Lodgaard had left.

Yes. Sverre became director of UNIDIR. I was a little surprised when I did not find him at PRIO, because he was my strongest connection.

He was in Geneva.

I had no problem accepting Hilde’s authority though. I think she had more of a problem in exercising authority. For me, a director is always a director, whoever he or she is, and I take her word as an order.

She was a young woman. Did you have young female directors in Moscow at the time?

Absolutely not. But you know, everything was foreign in that situation. So, I had to adjust to everything. She explained to me that if I wanted to extend my stay the thing to do was fundraising, which again was a totally foreign thing for me. In the Soviet Academy of Sciences, we never did any fundraising. We just learned to do what we had to do.

I started writing applications and was surprisingly successful. I got a fellowship from NATO, I had a small grant from the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and another small grant together with NUPI for a project on UN peacekeeping. One thing led to another, and the half-year was extended to a year. When I now try to explain to myself why I have stayed in one place so long, I generally say that I came for one year, then for another, and ended up having stayed twenty-five. That is my explanation for the incredible turn in my life.

Brilliant Students and Security Dialogue

Did you get Norwegian friends? Did you socialize with other Russians in Oslo?

The only Russians I socialized with were fellow researchers at the Nobel Institute. Vlad Zubok, and then Constantine Pleshakov. They were historians, and the Nobel Institute had a fellowship programme. So, I met sometimes with them.

But my main milieu was PRIO, and the people I socialized with there were a group of young, brilliant students, who are still around in different positions. Tor Bukkvoll is at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI), Nina Græger at NUPI, Kjersti Strømmen works for the Norwegian National Broadcasting (NRK) in Beijing, and Kjersti Løken [Stavrum] is in the media. Sven Gunnar [Simonsen] is now an independent consultant, and Bjørn Otto Sverdrup has a leading position in Equinor [formerly Statoil]. They were the students that PRIO was incredibly happy to cultivate back then.

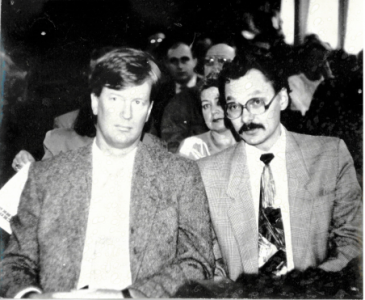

The delights of the PRIO Canteen in the basement of Fugelhauggata 11. Magne Barth and Pavel Baev in 1993. Photo: Sven Gunnar Simonsen / PRIO

Certainly, there were comings and goings. PRIO was a fluid environment. After just three years, I already felt like a veteran, with so many newcomers and departures around me. Magne Barth was my closest contact, but he also left, moving to the International Red Cross. So, I took over Security Dialogue from him.

How was it to edit Security Dialogue, which celebrates its first fifty years in 2019 (counting all the years of the Bulletin of Peace Proposals)?

It was hugely interesting. For a while I was there on my own, but then I got Anthony McDermott as co-editor. Dan Smith recruited him for the job. It was better to share the editing with Anthony, because this gave me more time for my own research. Certainly, editing a peer-reviewed journal was a challenge, maybe a bit too big for me. With hindsight I can say that. I did my absolute best, and we enjoyed doing it together, but I think Security Dialogue did much better later, when J. Peter Burgess took over.

Dan Smith Doubles PRIO’s Size

How would you characterize PRIO as a workplace, in comparison with the workplaces you knew from Moscow?

It was much smaller than most similar places in Moscow. For me, what was striking was the independence it had in expressing its views and opinions. I was also a bit surprised by how many comings and goings there were. I was used to more stable environments.

Around Easter 1993, my third PRIO Director, Dan Smith, took the reins during an identity crisis at PRIO, which had become too small and not financially sound. Dan’s response was more fundraising, and this became a guiding policy. Everyone was obliged to do fundraising.

Then the institute expanded. Dan took some difficult decisions, which did not sit well with traditional PRIO structures and patterns, but were remarkably successful. PRIO doubled its size and gained a new profile. It no longer focused uniquely on academic research, but entered the area of “engagement.” Under Dan’s leadership, PRIO was more engaged in all sorts of peace efforts than ever after.

He cultivated a close relationship with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and built up the Balkan and Cyprus programmes. We still have the Cyprus programme.

Yes, and there were several other experiments too, which could have led to similar expansion. In the autumn of 1995, I travelled with him into war-torn Grozny, which made a strong impression. When the first Chechen war was just about to end, an unhappy interwar period began. The Balkan and Cyprus projects were the largest of Dan’s initiatives. The Balkan one was huge, with a number of local offices in the various capitals of the former Yugoslavia.

We must remember, though, that it was also under Dan’s leadership that we decided to apply for a Centre of Excellence. The initial brainstorming for how to work out an application, how to proceed with it, was done in Dan’s time as a part of the same strategy of expansion.

Pavel Baev with former PRIO Director Dan Smith, travelling to Grozny in approx. 1995. Photo: Private archives

This was what became the Centre for the Study of Civil War (CSCW), directed by Scott Gates. Did you also take leadership responsibilities yourself?

Yes, I was very much involved in designing the application. One of the eight initial CSCW research groups was mine. The idea was to make sure that the Centre was firmly anchored in PRIO, connected with many parts of its research. It should not be a virtual Centre involving mostly foreign visitors. I think we succeeded with the CSCW, beyond expectations. The Centre became a very strong part of PRIO’s academic profile, but that was primarily in the period when Stein Tønnesson was director.

Am I Really a Peace Researcher?

You mentioned in the beginning of the interview that you had refrained from applying for jobs at NUPI that were right up your alley. You said that this was out of some kind of loyalty to PRIO.

Did it also count for you that PRIO is a peace research institute? Has it been a selling point for you that PRIO is about peace, not security?

That is a question I have often asked myself throughout my years at PRIO: am I really a peace researcher?

I’m certainly not a peacenik in the full sense of the word. Many parts of my research are about security, power relations, war and conflict – particularly in the former Soviet Union – and not so much about peace. But what impressed me at PRIO from the very beginning was how open it was to different perspectives. The focus was not on expressing ideological dogma but on banging our heads together and seeing what we could produce collectively through brainstorming. For me, that was very important.

What impressed me at PRIO from the very beginning was how open it was to different perspectives. The focus was not on expressing ideological dogma but on banging our heads together and seeing what we could produce collectively through brainstorming.

As for that very noble part of the PRIO identity – that we are not just doing interesting research and developing theories, we have a purpose to make sure that peace comes closer – I think it is important. Maybe not in a direct way, such that each project application must contain the idea of world peace, but in the sense that I have not really wanted to work once again, as I did in Moscow, with a think-tank closely related to national foreign policy making. I wanted something with more independence and with more freedom to shift from one idea to another, not just follow the demands of any particular political party.

That is probably my primary reason for being at PRIO as well. I do not want my research to be directly associated with foreign policy making. NUPI, of course, is not just that but also an institute of international affairs.

It is. It belongs to that family of institutions. It is a good family and I have associated with for instance IFRI (Institut français des relations internationales) in Paris, which is also a part of this family. I have worked with colleagues from NUPI throughout my whole time at PRIO, even today. We develop joint projects and I find it very productive. There was never any animosity or hostility.

The American Attraction

While in Moscow, you studied the United States, and since you came to Oslo you have gone to the US many times.

Yes, that was my main subject of research while working in the military research institute. US foreign and security policies are still a very interesting object of study for me, so I travel to Washington several times a year, where I am affiliated with the Brookings institution. I value this connection very much, because I still think that with all the ups and downs in US foreign policy making, Washington is a hugely important place, not only for global security, but also for global peace.

I have noticed that you tend to thrive in Washington. You write these short, sharp analyses of current events of a kind that the Americans appreciate. You also sent your son to study in the United States, or he perhaps decided himself?

That was very much his own decision, and it was driven by the fact that in the United States the education system includes college sports. He played tennis from an early age, and in his age group became Norwegian champion, so he wanted to continue. His college wanted him as a tennis player and paid more than half of his tuition fee. Otherwise, I could not have afforded his education there. I was pleased to see that his four years there were as happy and intense as my five years in Moscow State University had been.

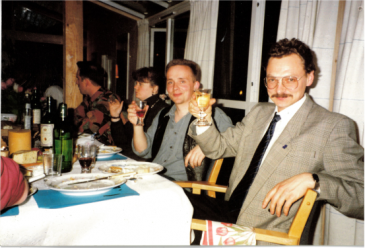

1993: Tor Bukkvoll and Pavel Baev raising a toast of welcome for the new PRIO Director Dan Smith.

Through Norway to America in a Quest for Recognition

Do you think your son Fyodor will settle down in Norway?

That is a difficult question. It engages the same kind of never-ending identity struggle that I am conducting myself. From very early on, I decided that I cannot become genuinely Norwegian. I am doomed to remain a rootless cosmopolitan, and this country is generous enough to accept that. As for him, while he now has a good job in the United States, paying well, and a girlfriend there as well, I think he can never become a genuine American. A big part of him is Norwegian, and I think his heart is in this country. I think he probably fancies very much, at some stage in his career, to return.

I wonder if I could ask you about your personal feelings concerning the United States. Many PRIOites have double feelings about that country. The institute has its origin in very strong criticism of the United States as an imperialist and war-prone power. The Vietnam War accentuated that, the war in Iraq the same, and now there is a fear that President Trump may unleash a war with Iran or even China.

On the other hand, the United States is the homeland of our main research partners, almost matching Sweden as our best research connection. We see the conferences held by the US-based International Studies Association (ISA) as the main place to meet up with colleagues and test our research findings. How have your feelings towards the United States developed over the years, and how do you assess the American presidents that have served in your time?

I arrived at PRIO during the Bill Clinton period. It was a legend at PRIO that in his youth Clinton had visited our institute. So, at that moment we had a perception that with this president the United States could become a powerful contributor to conflict management in the right way, a hope that US policy could be intoned with the PRIO mandate for peace making. It felt natural to build close research connections with the United States, and the creation of our Centre of Excellence facilitated those connections.

As far as international relations are concerned, the strongest academic institutions are in the United States. You may call it our peer review environment. We judge the value of an article, a project or even other activities on how it is evaluated in the United States. If it is strong enough to make a difference there, if it is really noticed there, appreciated there, we feel that our work is being recognized. I value my connections with Brookings and some other US think-tanks very much. I see them as beneficial for PRIO, strengthening our international profile.

And who is the best president the United States has had since the 1970s?

I would still give my vote to Barack Obama even though he disappointed in many ways. You may argue that Trump’s election was a consequence of the Obama presidency, of the deep hostility generated among many American voters by Obama’s coming to power. Yet I would not blame him for this.

I think [Putin] is a disaster for Russia. He is taking Russia into a dangerous dead-end. He presides not only over Russia’s decline, but possibly over its demise.

I do remember, at the very start of his presidency, that I was asked what he would concentrate on during his first 100 days. I said he would seek ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Yet it never happened. The US Senate has still not ratified it today. I do not think it was a good idea to award the Nobel Peace Prize to Obama at the very start of his presidency. Nevertheless, I think he probably deserved the prize.

Since we are talking about presidents, could you express your feelings towards Vladimir Putin?

I think he is a disaster for Russia. He is taking Russia into a dangerous dead-end. He presides not only over Russia’s decline, but possibly over its demise. I worry about Russia’s trajectory under his leadership, and I hold him responsible.

A Military in Trouble

When you came to PRIO you were a Soviet expert on the west, but not really an expert on Russia or the Soviet Union. How did you change your research profile after you had come to PRIO?

Well, it was a period of catastrophic change. We all have to evolve. When everything changes beyond recognition around us, it is impossible to stay on the same track. Reinventing myself was natural and also interesting.

One obvious topic for me was the consequences of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the conflicts that erupted in its wake. All in all, the collapse was remarkably peaceful, astonishingly peaceful I would say, but the Caucasus became the area where all sorts of small conflicts tended to ignite one another in a kind of chain reaction. This was a relevant topic for PRIO. The Balkans was for me a foreign territory, but I felt that with my knowledge of the Caucasus and my ability to draw on connections there I could deliver some insights.

For me, another topic I could study from a certain level of competence was the Russian military, which was also a prime instrument in the conflicts of the Caucasus and at the same time was shrinking and going through a colossal identity crisis. That change in itself was so interesting that it became the main topic of my first book.

Could you interview your father about the Russian military?

Of course. I discussed many things with him. The whole family, on the male side at least, had strong connections with the military. My two grandfathers were in the military, my father was a military intelligence officer, my brother was a young captain back then. My cousin was in the navy. So, as far as first-hand sources were concerned, I had no shortage. But for many of them the shock of the Soviet military’s decline was profound, even bitter. My cousin was not able to take it – he died very young.

Can you tell a little bit about your first book?

It was called The Russian Army in a Time of Troubles and was mostly written in 1996. It took a couple more years to complete it though, because I was involved with Security Dialogue. I studied the Russian army’s retreat from Eastern Europe, its painful reforms and contraction, and its engagement in several armed conflicts from the former Yugoslavia to Tajikistan.

I think my research topic really demanded attention. If you look inside the cover of the book, you will see that I dedicated it: “To my grandfathers, who both were colonels in the Soviet Army. To my father, Captain of the First Rank (ret.). To my brother, Captain in the Russian Army. And to my son, who will – I hope – choose a different career”. This book was my first big accomplishment at PRIO, and it helped me get a permanent position. After that I became a Norwegian citizen, and after that again I became a research professor. So, these were steps up in my career, and important landmarks in my life.

Was it evident to you that you would apply for Norwegian citizenship, or was it painful in any way?

It was not painful at all. By that time, it was quite natural. Our little family had settled happily here.

So, Olga is also now a Norwegian citizen?

Yes, of course.

And your mother-in-law now lives with you here?

Yes, she moved in with us a year and a half ago. She is a lady of mature age. She cannot really manage on her own in Moscow.

Your first book also impressed the Norwegian Ministry of Defence. They showed a strong interest in your knowledge about the Russian military, so they funded many of your projects at PRIO. How was it to work for the Ministry of Defence in a different country from the one you had grown up in?

It was interesting. I was surprised by the flexibility of the Norwegian Ministry of Defence. How open it was to discuss new ideas. How open-minded the bureaucrats were in comparison with the ones I had known.

While they also operated in uniform, and certainly respected discipline, they never really tried to prescribe anything. They funded my research and thus gave me the opportunity to do it, but they never tried to influence the outcome. That was, for me, something very important, and the same goes for PRIO. At the outset, receiving funding from the Ministry of Defence did not feel natural for my colleagues, but after a while, no one saw it as a problem.

Oil, Gas and Nuclear Modernization

Then you broadened your field of expertise to include the oil and gas sector.

I became interested in that area when looking deeper into how Russian foreign and security policies are made. The instrument of oil and gas became just as important as military power. And this led to a quest for politicized control over the oil and gas business. I also found interesting opportunities for fundraising, which became a natural part of my research. Whatever brilliant ideas you have, you still need to make sure that there is a sound financial foundation underneath. That was something Hilde [Waage] advised me to do. And that was PRIO policy under Dan [Smith]’s leadership. Whenever there is an interesting opening and you feel you can make a difference, I tend to go for it.

The Arctic became an interesting dimension in my research at the time when Artur Chilingarov famously planted a flag under the North Pole in 2007. It is not the same Arctic for me as for many environmentalists, ecologists and NGO activists. For me, the Arctic is interesting in terms of what it shows about Russian foreign and security policy. For the same reason, I have become interested in Russia-China relations, so I established a connection with you, Stein, so we could make several interesting trips to Asia together and write some joint articles.

And now I see an opportunity to return to nuclear matters. I see a deep contradiction between the ongoing nuclear modernization and strengthening of many features of nuclear deterrence systems and a strong political drive towards nuclear disarmament. Nuclear modernization and disarmament initiatives will have to coexist for many years to come. I think it will be interesting for PRIO to establish a forum where researchers engaged in nuclear modernization and disarmament can meet, interplay, and look for compromises.

Do you also follow the North Korean question?

I do, although Russia’s involvement is disappointingly weak. Nevertheless, it is an area for which I have developed a lot of interest and I hope to be able to design some research projects, probably not specifically on North Korea, but on nuclear security matters in East Asia, with Russia as a part of the equation.

Multidisciplinarity

Do you identify yourself as belonging to one particular research discipline?

I can probably say that International Relations is my discipline. I am not a great theorist; I cannot really design interesting mathematical models or build databases. So, for that matter I know the weaknesses of my research.

Very often, I also feel that the pressure of events is such that it is more important to write a short comment, a short memo with an impact factor, than to try to theorize and think it through while other events overtake your brilliant observations. How to combine the more fundamental and academic parts of research and the more current analysis is for me the most interesting challenge.

Pavel Baev representing the PRIO team in a volleyball match against the Red Cross upon moving in to new premises in Hausmanns gate in 2005. Photo: PRIO

When you came to PRIO you encountered a small environment, which has become much bigger, but it has always been multidisciplinary. You have met historians, legal specialists, political scientists, sociologists, anthropologists, philosophers, theologians as well.

Was this something you were used to? Has this been stimulating to you intellectually? Or would it have been better to work in a more specialist environment with people using similar methods and referring to the same theories?

Multidisciplinarity came naturally for me. Besides the military research institute where I worked, I was familiar with several other institutes in Moscow as well, like the USA and Canada Institute, where I defended my PhD. They were always very multidisciplinary, with historians and cultural studies, and even literature. I think bringing together different perspectives is a huge advantage of PRIO and we should cultivate that further.

PRIO’s Strengths and Weaknesses

How do you see the system of decision making at PRIO? Is it run effectively, is it participatory, does the leadership consult sufficiently with the staff? And how has this changed?

It has certainly evolved. A system that worked for an institute of 25 people cannot be the same for 75 people, plus affiliated researchers and associates. It has evolved, and PRIO is now more structured – with real departments – than the PRIO I arrived to.

Decision making is done by the leadership group primarily, and not the Institute Council, as was the case when I arrived. Certainly, there are always some problems with decision, particularly with regard to hiring new staff. Some of the hiring was quite successful in my early days. Inger Skjelsbæk came and remained at PRIO for many years. Henrik Syse and Greg Reichberg are still my colleagues. Some other decisions of this sort were probably less successful, and some of them were troublesome. So, PRIO now has a much more established recruitment policy, with more thorough and competitive processes.

Financial discipline is also something that is difficult to achieve, because fundraising is never easy. Its success is never guaranteed. We always take chances. We have to apply for much more than we can handle, and then suddenly we find ourselves overloaded, or underfunded.

But I think, all in all, that PRIO has managed to overcome most of its challenges, and I think the decision-making system has gone through an evolution in a remarkably conflict-free way, and become something we all agree to. The Institute Council has less decision-making power now, and this has become natural. Decision making is far smoother when it is done by a smaller group of people around the table, with long discussions in a tight milieu, than in a meeting of fifty people.

Pavel Baev to the left, a member of the PRIO board in 2004. Other members: Martha Snodgrass, Raimo Väyrynen, Mette Halskov Hansen, Øyvind Østerud, Cathrine Løchstøer and Bernt Aardal. Photo: PRIO

What would you see as the biggest change that has happened at PRIO since you came in 1991/92?

Size certainly matters. So, growth was probably the most important change. Now, when I say anywhere in Europe that “I work in a small research institute in Norway with about 75 people,” it is often a shock. The normal size of European research institutes is still some 15–20 people, 25 at best. Probably, we are as big as any European institution of this sort. We are not exactly a think-tank, and not exactly an academic institution. We are an interesting cross-breed, a mixture of several different traditions and patterns, and I think this is one of our main strengths.

We value our academic profile, that is one of our strengths. Connections with the International Studies Association. Our peer-review journals. At the same time, our policy orientation, which is the think-tank part of our activity, and engagement in the field in different ways. These are the main parts of PRIO’s identity. I think they come together organically. They are drawn from different traditions of peace research, but have always coexisted and are never really in conflict.

How influential do you think PRIO is in Norway and in the world?

It is difficult for me to judge about Norway. I have always tried to keep a distance from policy making. But I think that PRIO has managed to connect with Norwegian decision making, particularly with the Foreign Ministry, probably less with the Parliament. That is a big difference, I feel, from for instance Washington, DC, where think-tanks have strong connections with the US Congress.

At the same time, PRIO’s reputation is much stronger in the area of academic research. With the International Studies Association, our journals, and our strong heritage from the Centre of Excellence, we are able to carve out a very specific niche in several disciplines. Yet we are not so much engaged in international political decision-making. We are probably less involved in Brussels than NUPI, less able to influence EU and NATO decision-making. Maybe it is good to have that difference from other European think-tanks.

I think the EU bureaucracy in many ways is its own worst enemy. The ways in which it organizes its decision-making and funds research is so awkward, so cumbersome, and makes it so difficult to deliver on all the requirements and paperwork. It sometimes feels that it is not worth even trying.

So, I think PRIO has a strong enough profile, where it matters. The environment where we could probably have made a greater difference, with our size, is the peace research environment. I am not entirely satisfied with how the International Peace Research Association works, in how this whole family of peace-loving institutions connect with each other. There are certain weaknesses here, and often you encounter various identity crises. The connections, even with SIPRI, are not as strong as they should be.

Going to Work at PRIO

One last question: could you try to describe your travel from home in the morning to PRIO? How you travel, what you think about, what you feel when you enter PRIO, where you enter, what the first things you do are, and how you start your work day?

It is a very short journey. I live up the Holmenkollen hill, three minutes’ walk from Gråkammen T-bane stasjon (metro station). Often I make a longer walk to Ris stasjon, just to have some exercise and clear my head. I love thinking while I walk. Typically, while walking I try to sort out what kind of problems the day has in store for me, what sort of surprises I may expect in my inbox. Then it is a 15-minute ride on the T-bane to Oslo Sentralstasjon, and another three-minute walk to the backdoor of PRIO. I normally enter through the gate from the back, not through our main entrance. It is a little bit shorter.

I enter my office […] generally with a very good feeling that life is interesting, life is great fun – that I expect something I never thought of to change my day beyond recognition

I think one of the important impressions you get at PRIO is the smile that meets you from behind the reception. From Cathrine [Bye] or anyone else who works there. It immediately lifts the spirit of any visitor, gives a feeling of being welcome. I think that is an important part of our identity.

Then I register my arrival with my card, enter my office where we are sitting now, switch on the computer, generally with a very good feeling that life is interesting, life is great fun – that I expect something I never thought of to change my day beyond recognition. And there are always good colleagues around. PRIO feels particularly friendly and cheerful in the morning.

Thank you very much, Pavel.