On 23rd March the United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, called for a global ceasefire to combat the coronavirus pandemic. The appeal quickly gathered widespread support, and has already led to ceasefires by conflict parties in more than 12 countries. Strikingly, this includes a arrangements in Yemen, Afghanistan and Syria, three countries that have recently experienced some of the world’s bloodiest conflicts. But why do parties agree to ceasefires, and can they make a difference during this crisis?

Afghan Soldiers in 2010. Photo: ResoluteSupportMedia via Flickr

Ceasefires in civil war

Ceasefires are a relatively common feature in civil war. They are used in very different ways, and vary widely in intention, content, timing and duration. Our knowledge about ceasefires is surprisingly limited when it comes to answering questions about when and whether they are effective, why they are entered into, which parties want a ceasefire and why. To address this deficit researchers at PRIO and ETH Zürich have collated data on ceasefires. Between 1989-2018 we found evidence of at least 2,300 ceasefires during civil war.

Who participates in ceasefires?

Many of the ceasefire we captured are unilateral, including only one party. On other occasions, ceasefire can be reciprocal, or bilateral. For example, where one party declares a ceasefire in the hope that its opponent will also declare its own ceasefire, or where two parties simultaneously enter into an agreement. In our data around one-third of ceasefires are unilateral. The remaining two-thirds are bilateral ceasefires, which are agreements between two parties, or multilateral ceasefires, which are between several parties.

Ceasefires are not always between the main parties to a conflict. In Afghanistan, a ceasefire was agreed earlier this month between the Taliban and a third country (the United States). The goal of such agreements is to create scope for dialogue between the main parties. We have examples of similar processes in Syria, where third countries such as Russia and Turkey have played active roles.

Why do parties enter into a ceasefire?

Ceasefires can perform a variety of different functions, ranging from short term immediate objectives to playing important functions as part of the peace process. They can occur early in a peace process, with the goal of fostering trust, demonstrating control over the parties’ respective military forces, and protecting civilians. On other occasions ceasefires are intended primarily to create a good climate for peacemaking negotiations by ensuring a cessation or reduction of violence while negotiations take place. Definitive ceasefires, which occur at the end of a conflict, are a tool to end a conflict, setting the various disarmament, and demobilization of rebel groups.

The parties to a conflict do not always have honourable intentions when entering into a ceasefire. In Yemen, there have been several ceasefires between the Houthi militias (known formally as Ansar Allah) and various ethnic groups. The Houthi’s objective was not to improve the situation, but to negotiate ceasefire agreements so that they could reach Yemen’s capital more easily and overturn the sitting government.

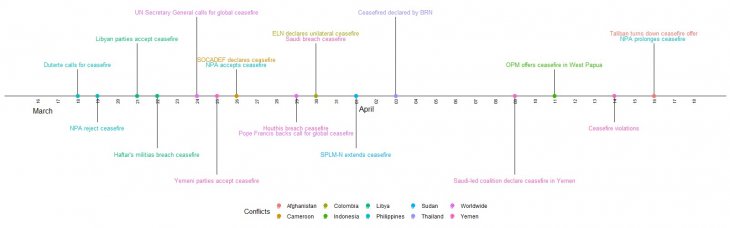

Timeline by Fredrik Methi.

Humanitarian Ceasefires

There is also a precedent for ceasefires responding to humanitarian disasters. Approximately a third of the ceasefire captured in our dataset had humanitarian motivations, for example after a natural disaster, facilitating vaccination programmes, or religious festivals. In the Philippines, for example, a Christmas ceasefire is declared every year.

We have observed a number of humanitarian ceasefires in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Even before Guterres called for a worldwide ceasefire, several rebel groups and governments had entered into ceasefires on their own initiative. In the Philippines, President Duterte declared a unilateral ceasefire in the conflict with the CPP; the warring parties in Libya agreed on a humanitarian ceasefire; and in Afghanistan the Taliban have agreed to allow health workers safe conduct.

Following Guterres’ call, in recent days we have also seen ceasefires in Syria, Yemen, Ukraine and Cameroon. These ceasefires are linked to the coronavirus pandemic, and are not intended to result in lasting peace. But there is example of humanitarian ceasefire leading to peace. For example, following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) entered into a ceasefire with Indonesian authorities. Six months later this process led to a peace agreement that ended the 30-year insurgency.

Peace in the time of COVID-19…and beyond?

The ceasefires we have seen in recent weeks have a clear and limited humanitarian purpose. In the past, humanitarian ceasefire tend to be successful when the remain distinct from the conflict dynamics, and so it is important that attempts to build a broader peace don’t undermine the clear and pressing humanitarian function. That said, there is hope: PRIO Practitioner Borja Paladini Adell writes that this new global collaboration could yield positive results. The arrangements do offer a small opportunity for the parties to work together to manage the current crisis, that might yet lead to more significant progress towards peace in the future.

[…] Ceasefires in the Time of COVID-19 – Siri Camilla Aas Rustad, Tora Sagård, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, Govinda Clayton and […]