New research shows that existing economic forecasting models vastly underestimate the impact of conflict on marginalized countries.

National income for war-torn nations like Afghanistan, Niger and Yemen could be up to 50 to 70 per cent lower than existing estimates by the end of the century.

Photo: EU/ECHO/Peter Biro / Flickr / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

When considering what our future will look like, one of the most critical inputs is the rate of economic growth. Long-term projections of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are essential for estimating the impact and economic cost of climate change, and other social development outcomes like public health, food prices and armed conflict.

To have an idea of what societies will look like throughout the 21st century, projections of GDP per capita are needed; the average incomes across the countries of the world. Such projections exist and are widely used.

However, the most prominent ones are based on economic models that are developed based on well-functioning economies in the West and applied globally. They are founded on projections of future demographic changes and education levels, as well as an expectation that technological change will gradually improve productivity.

The models assume that less advanced economies will adopt these technologies and gradually, but inexorably, converge towards income levels of the West.

This thinking has been wrong.

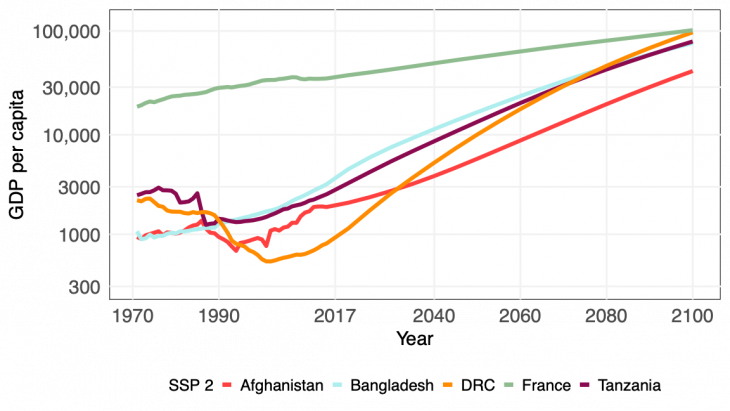

Take the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) prominent economic growth model below, which shows GDP per capita for Afghanistan, Bangladesh, France and the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1970 to 2016, and projections from 2017 to 2100. It forecasts that France will continue its steady economic progress of the past 50 years at roughly the same pace. Bangladesh is predicted to have about 60 per cent of France’s GDP per capita at the end of the century, having benefited from sound economic policies in the past.

But now consider the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It was richer than Bangladesh in 1970, but after 30 years of Mobuto’s corrupt government and a devastating civil war, it was much poorer in 2016. In the year 2100, the OECD model projects it to be as rich as France. Projected growth for Afghanistan is similarly overly optimistic, given its unstable political development.

The conflict trap

The major problem with existing growth models is that they ignore the economic effects of armed conflict and poor governance. They expect a country like the Congo to converge to the income level of France, as soon as indicators like education and technology catch up.

Current models do not take into account the destruction caused by bullets and bombs. They make little room for the lack of interest or capacity of weak governments to invest in growth-promoting infrastructure, such as roads and electricity. They do not factor in the likelihood that citizens with skills and resources may flee to safer places than the Kivu provinces of Congo when violence erupts.

In a recently published paper, we put forward a new model that incorporates the likely economic costs of armed conflict into forecasting the economic outlook of a country. The findings are striking.

The estimated correction required to account for armed conflict is substantial – expected national income is 25 per cent lower on average by the end of the century across countries when taking conflict into account.

Strong regional patterns in countries with multiple conflicts are projected to experience much higher conflict burdens and reduced economic growth by the end of the century. Countries such as Afghanistan, Niger, Yemen and the Philippines are projected to lose 50 to 70 per cent of their potential income over the next 80 years.

We also found that armed conflict has strong detrimental effects even in large countries. Armed violence in the northeast of the Congo affects growth rates across the entire country – the government must reallocate resources to improve security in conflict hotspots, and communities flee to safer parts of the country, placing additional burden on social services and infrastructure in places where they seek refuge.

The implications of these findings are grave.

Today’s most marginalized societies will be substantially more vulnerable to the impact of climate change and other challenges than indicated by existing income projections. If our projections hold true, the quality of governance and capacity to handle the impacts of climate change will be much more pessimistic than previously expected.

Persistent conflict affects population health, migration patterns and undermines education. All of these, in turn, alter the likely future growth paths of nations. While these effects will be concentrated in countries where the conflict occurs, they may also be experienced regionally in countries that share borders, and more generally through changes in trade and other political spillovers.

Economic projections that do not account for the effects of armed conflict and broader governance failures on economic growth underestimate the challenges faced by poorer nations. Such political factors will continue to undermine efforts to reduce poverty and manage the adverse impacts of climate change.

Planning for our shared future on a changing planet requires scenarios that explore all the challenges we will face, especially where history suggests that we must guard against more pessimistic outcomes.

The authors

- Håvard Hegre is a Research Professor at PRIO and the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University

- Kristina Petrova is a PhD student at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University

- Gudlaug Olafsdottir is a PhD student at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University

- Elisabeth Gilmore is an Associate Professor at Carleton University