Thank you to PRIO for the opportunity to join you today and to Congressman John Lewis for his insights into the use of nonviolence in the American civil rights movement. [This text is a transcript of Kathleen G. Cunningham’s comments to John Lewis’ PRIO Annual Peace Address].

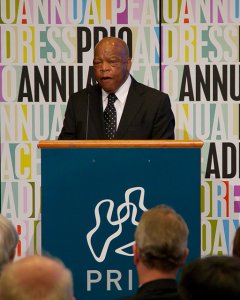

John Lewis giving the PRIO Annual Peace Address in 2011.

What I hope to add today with my own comments is a synthesis of the scholarship on nonviolence with the realities of nonviolent struggles today and to explore the pressing policy questions that emerge from the study of nonviolence and its application to these real world challenges.

Let me begin by highlighting the phenomenal changes we have seen these past months in North Africa and the Middle East and roles that violence and nonviolence have played there. As you all know, in the past 10 months, we have seen social revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, civil war in Libya, uprisings in Bahrain, Syria and Yemen, and protests breaking out in a number of other countries. Many of the struggles have relied on nonviolent tactics to press their governments for radical social change. In some cases, violence has erupted between protesters and government forces. In others, we see large scale uses of violence.

These movements, both nonviolent and violent have led to concessions from a number of governments, and three regime changes, but also to repression and conflict. These events were both riveting and in some ways shocking. Few would have predicted this change, or the means through which it occurred. The possibility of radical social change brought about through nonviolent protest in the Middle East was not something many people were entertaining prior to the mass protests in Tunisia.

These events, and in particular the stark comparison of how social change was achieved relatively peacefully in Tunisia and Egypt but though violent upheaval in Libya, have recalled the necessity of understanding when civil resistance can work, and why protesters turn to violence in some cases but not others.

Historically, much of the scholarship on nonviolence is instructive, descriptive, or normative. The work of Gene Sharp, for example, has served as a practical guide for nonviolent resistance and played a role in struggles to overturn dictators around the world. Sharp, and those that followed him, help us to understand what it means to apply pressure without using violence, and the ways in which this can be achieved – from sit-ins to mass protests. Other works provides inspiration to adherents of nonviolence through descriptive narratives of campaigns around the world from Russia to the United States to India and beyond. Critical lessons from the American Civil Rights movement and other successful campaigns for social change have illustrated the power of nonviolence in achieving these changes.

Many studies of nonviolence have emphasized the goal of delegitimizing one’s opponent or restricting an adversary’s use of power. Work on regime change in El Salvador and South Africa, for example, focuses our attention on the ability of civil resistance to impose costs on the state. Importantly, this ability is linked both to strategy choices of the resistance movement, and to the extent to which mass mobilization can be achieved.

Quite recently, there has been a shift in the study of nonviolence toward trying to understand its efficacy, that is, how and why civil resistance works. One study compares successful and failed nonviolent campaigns, showing that tactical innovation plays a role in determining which campaigns succeed. Indeed, the use of social media, such as twitter is presumed to have played a role in the recent successes in the Middle East. Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan’s recent book Why Civil Resistance Works compares the violent and nonviolent campaigns. They argue that nonviolent campaigns draw more participation and in doing so, are able to create a fairly stable base of supporters who are willing to impose costs on the state.

Strikingly, Chenoweth and Stephan find that nonviolent campaigns are twice as likely to succeed as violent ones. This runs counter to many people’s impression that resorting to violence is the more effective way to impose costs on the state.

This recent scholarship on the success of nonviolence had highlighted an important gap in our understanding of the efficacy of nonviolence in different contexts. The recent social revolutions in the Middle East have brought this issue to the forefront. Many of those movements had peaceful roots, but only some survived as large scale nonviolent campaigns.

Several central questions emerge from this:

First, the relative success of nonviolent campaigns appears to be limited, to some degree, to pro-democracy movements. Research shows that nonviolent campaigns are much less successful when focused on the issue of territorial control and secession. Few groups are able to secede in the contemporary international system, but the dominant strategy through which this is achieved is violent resistance. This is troubling because war over national self-determination has become the most common type of conflict in the international system in the past few 40 years. Cases such as Chechnya and the Tamils in Sri Lanka exemplify these disputes. There is also a great deal of potential future conflict over this same issue. Since the end of the Cold War, there has been a steady increase in the number of minority groups seeking greater self-determination over time.

Thus, we have some reasons to believe nonviolence works, but not particularly well for one of the more pressing challenges in the international system today. Why that is the case, and how it can be changed, is a critical question for the future.

A second question emerging from the evaluation of whether and how nonviolence works relates to the necessity of mass participation. Scholars and practitioners alike highlight the importance of mobilizing people in large numbers. Yet, we know little about the conditions under which this is likely to happen. The success of nonviolent campaigns hinges on achieving a high number of participants, and this can create a substantial problem of collective action. Moreover, many civil resistance movements are met with repression, which creates a strong disincentive for individual participation.

How do some campaigns overcome this? The ability to generate mass mobilization is likely to be influenced by a number of factors, such as the nature of the movement (be it regime change, pro-democracy, or separatist). The resources available to supporters, and support from actors outside the movement, such as kin living across borders and the international community, can also play a critical role in mobilization. Moreover, many successful campaigns for social change are inspired by charismatic leaders, such as Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and Mahatma Gandhi, and sustained by continual acts of courage and commitment by leaders such as Congressman Lewis.

Our understanding of how and why different factors contribute to the success of nonviolent resistance remains limited, despite the wealth of practical and normative work done in this area. This question should be the focus of sustained research, much in the way that we have endeavored to understand the outbreak and consequences of violent campaigns.

Finally, we need to integrate our increased understanding of civil war and social violence with an understanding of nonviolence. Studies that evaluate the effectiveness of nonviolence have largely been comparisons of their success and failure, or more recently whether violent or nonviolent campaigns are more effective. What is missing from this existing approach is that nearly all movements for political change involve elements of moderation as well as radicalization.

Let us return to the example of struggles for national self-determination. Even among the most conventional political struggles, such as the Jura movement in Switzerland, there were elements of strategic violence

Moreover, disputes rife with violent conflict, such as the Chechen movement, contain organizations that forge ahead to seek political change by eschewing violence. Indeed, many social movements appear to be engaging in both violent and nonviolent resistance in an effort to secure political change. At times, organizations within these movements change strategies – transitioning from freedom fighters to activists and vice versa.

If organizations seeking political change make strategic choices about whether to use violence or nonviolence or both, then we need a better understanding of when and why they chose a particular strategy, and why individuals choose to participate in one way or another. Part of the answer is likely to be related to what others are doing, especially since successful nonviolence requires mass participation. But there are likely to be other factors that influence the strategic choices that these organizations make, and these are likely to change over the trajectory of a campaign. Thus, understanding incentives for the use of both violence and nonviolence at both early and later stages of social upheaval is important.

These questions, and the answers we hope to find, have important implications for real world policy choices. Recent events have shown us that the international community can play a critical role in determining the success of civil resistance, but it is not necessarily a straight forward role. If we return to the issue of secession, we can see clearly how the international community is both empowered and critically limited. Secession is nearly impossible without support from the international community. The referendum on independence in Southern Sudan highlighted the power of people to choose their own political future, but this ability is predicated on international support. Many groups that aspire to statehood hold similar referenda, but with little consequence. Yet the international community cannot universally support secession. States want to retain their own territorial integrity, and minority groups want to exercise their rights to self-determination.

How the international community responds to this tension is important. It creates incentives for separatists to use particular strategies, and this can make violence or nonviolence more or less attractive as a means to social change. We can see this same dynamic illustrated in the response of the international community to the Arab Spring. There was explicit support given for the armed overthrow of Qaddafi. Yet, we failed to see large-scale intervention in the cases of nonviolent resistance. This contrast may very well create incentives for the use of violence.

These are but a few examples, from which it would be quite difficult to discern a pattern of influence, and even more difficult to create coherent policy. We need greater attention to what kind of incentives the international community creates for agents of social change. Thus, there is a critical challenge for scholars and policy-makers alike. If we want to promote the use of nonviolence, we need to sponsor and engage in sustained research on it, such as the ongoing work at here at PRIO. We need to explore the conditions under which it is likely to work, and reach towards an understanding of what actions the international community can take to make nonviolence more effective and consequently more attractive to people earnestly seeking social change.

Thank you.

Kathleen Cunningham is an Assistant professor in the Department of Government, University of Maryland, and a Research associate at the Centre for the Study of Civil War, PRIO.