Helga Hernes, Senior Advisor at PRIO, at the international conference ‘Women, Power and Politics’ at the Nobel Peace Centre in Oslo, 14–15 November 2013. Photo: Julie Lunde Lillesæter/PRIO

Helga Hernes, interviewed by Kristian Berg Harpviken

Helga Hernes coined the term ‘state feminism’ in the mid-1980s. At the time, suggesting that the state could be women friendly and an ally in the struggle for women’s rights was controversial. A decade and a half later, however, the term had become widely used. ‘State feminist’ is indeed the best description one can find for Helga Hernes. She has used her academic as well as her political positions as platforms for advancing gender equality and women’s rights at a national level. In 2006, she arrived at PRIO, bringing her scholarly, activist and political experience to inform research associated with UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security.[1]

Helga Hernes was born in Western Prussia (now part of Poland) in 1938. She experienced war and its consequences as a child, grappling with her country’s history as she grew up, and becoming deeply disappointed with how slowly German society came to a recognition of responsibility. In her late teens, inspired by her American grandmother, and by encounters with a benign American occupying force in Germany, she left for the United States. There, she pursued her education at top-ranking institutions, while engaging in both the anti-Vietnam war protests and the struggle for civil rights.

In Norway, which she made her base in 1970, Helga Hernes has left a mark in many societal domains:[2] as an activist against nuclear arms and for gender equality; as an academic pioneering gender research and heading several national institutions; as a politician serving as Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time that the Cold War came to an end; and as a civil servant, where she drew on her personal network and institutional knowledge. She has always been modest about her own achievements, and this interview offers a rare opportunity to gain closer insights into what she stands for, and what her many contributions have been. A foreigner who made Norway her home, Helga Hernes could see clearly what to most Norwegians seemed entirely natural about their society. Throughout, she has shown a consistent commitment to academic quality in pursuit of a just and peaceful world.

Kristian Berg Harpviken: Helga, you are generally referred to as a ‘state feminist’, and you were actually the person who coined the phrase ‘state feminism’, isn’t that right?

Helga Hernes: Well yes, the process of coming up with the term state feminism took me about 10 seconds. I’d written a book as part of a series in English, and the editor at the publishers phoned me and said he needed a title for my book by the next day. I simply said: ‘It must have something to do with power… I’d suggest Women and Power: Essays in State Feminism.’ It took 10 seconds.

We will talk a great deal about your political efforts in support of gender equality, but let’s start with your commitment to peace. It is correct that this started with the campaign against nuclear weapons?

The Fight against Nuclear Arms

I woke up last night and looked through my old files. In there I found a newspaper cutting with a photograph of myself. It’s a good thing to be self-centred, you know. To collect things.

I was young, and suddenly I was in the papers. I’d landed at Flesland Airport just outside Bergen, and two colonels and a general were standing there. They all stood to attention. But it wasn’t for me, it was for another general.

So the officers weren’t there to welcome the peace activist?

No, certainly not. But I was very happy to be able to get involved in campaigning for peace along with Ingrid Eide, Mari Holmboe Ruge, Eva Nordland, Berit Ås and many others. There were really a lot of us.

You were all involved in Women for Peace?

Yes, the organization was called Women for Peace. It was founded in the late 1970s. The reason we became important, and that I became a real activist, was the NATO ‘dual-track’ decision on 12 December 1979 to deploy medium-range and cruise missiles in Europe, unless the Soviet Union agreed to withdraw its SS-20 missiles. We weren’t completely successful. But even so, the position adopted by Norway in Washington was significantly moderated.

A key issue, especially for me, was to prevent the two Germanys attacking each other with nuclear missiles if it came to war. A nuclear war on European soil, particularly between two countries that actually used to be one, would have been a catastrophe. I think that’s why I became so very actively involved. Because it was deadly serious. Thorvald Stoltenberg [Minister of Defence 1979–81] and Johan Jørgen Holst [State Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1979–81], and unfortunately also Gro Harlem Brundtland [the deputy leader of the Labour Party, who became Prime Minister in 1981, the first woman in the post], were ‘all for it’. And the American pressure was enormous.

Yes, it’s clear that it was. What work did the organization do?

I gave countless lectures. I’d imagine that there was a majority in the Norwegian population against the dual-track decision. Because it brought people so close to the reality of what nuclear war would mean. So close. Even if Norway were not involved itself, because of course you had a resolution on nuclear weapons [No nuclear weapons on Norwegian soil] and so on, it would still have been completely dreadful. There would have been a world war.

And then you were appointed as a member of the government’s Disarmament Commission?[3] So that meant that you were combining being a civil society activist with a position within the political elite?

Absolutely. But I wasn’t the only one. I remember that someone came from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and tried to object to us. I don’t know if you know who Helge Sivertsen was? Helge Sivertsen [Oslo’s Director of Education 1971–81 and a former Minister of Education] was a fantastic pedagogue and teacher, and he was also a pacifist and Labour Party member. He took a very principled position on this point. He didn’t let himself be picked on. I must say that I think it was almost comical that we, as a government-appointed Disarmament Commission, should get such a burning hot issue on the table. Undoubtedly that was something no one had anticipated. But I didn’t have a bad conscience about it. What was the name of the psychologist? Yes, she was Wenche Håland from the University of Bergen. She was a very important voice for peace, and saw this as a very important appointment. There were only three or four of us. We were a minority on the Commission, and Helge Sivertsen abstained from voting, although I think he would also have had some qualms. But of course, both the Minister of Defence and others tried to convince us that this wasn’t our business. That it didn’t come within our mandate.

But did the Disarmament Commission itself have major influence?

No.

Even so, there must have been a certain amount of status attached to just sitting on the Disarmament Commission.

Of course! It gave us a platform. When I travelled around with Women for Peace, I was travelling as a Woman for Peace. I wasn’t travelling as a member of the Commission. But that was a time when there was a lot of status attached to being a woman and being politically active. And it was really fantastic when we arrived in different places. I don’t know whether you’ve been to Western Norway with all those tiny islands, but it was very, very exciting how engaged the people were. They arranged fantastic dinners. It was really much more exciting than arguing with the AKP girls [activists linked to the Maoist Workers’ Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) or AKP-ml]. Because they wanted to make the issue theirs, of course, but that wasn’t tolerated by Eva Nordland or Mari, or in particular by Ingrid. There were others involved too, such as the educator Birgit Brock-Utne. This women’s struggle was at least as important as the others we were engaged in.

Of course there were some of us, such as Birgit Brock-Utne, who emphasized female qualities, but I never did so. I was in favour of equality and I said that women should be valued the same as men. That was my only demand. Nothing else. I wouldn’t have anything to do with women being soft, fine, lovely creatures. I wouldn’t have anything to do with that. And I also wanted men to share the work of looking after children. That was a very primitive and simple demand, seen in today’s context. But it wasn’t particularly well received.

[T]here were some […] who emphasized female qualities, but I never did so. I was in favour of equality and I said that women should be valued the same as men. That was my only demand. Nothing else. I wouldn’t have anything to do with women being soft, fine, lovely creatures.

Was it very controversial to believe that women were not necessarily more peaceful by nature than men?

Yes, they didn’t like to be told that. That’s what I said. I said it all the time, wherever I found myself: ‘Women are not better people than men.’ The fact that we were fighting was just because we wanted to have equal rights with men, it didn’t have anything to do with us having superior natures. But there are still feminists who believe that women are better people than men, more peaceful and so forth. That’s not true. Well, I don’t think it’s true. Let me put it like that.

No doubt we’ll never be completely rid of this disagreement. But this is very interesting. So in the 1970s, you worked as a peace activist with people whom you would later work closely with – or against – in the political sector? For example, you later became State Secretary for Thorvald Stoltenberg?

Yes, and I was good friends with Johan Jørgen and his wife. But when Thorvald, as Minister of Foreign Affairs, invited me to join his team in 1988, I didn’t really think so much about the period when I had encountered him in my capacity as a disarmament activist. Obviously, that had to do with his personality. He never mentioned it. The only agreement I had with Thorvald about myself and my political views was: ‘Thorvald, I’m not a pacifist, and I’ll never be a pacifist, because I grew up in Hitler’s Germany. I can’t be a pacifist. But I’m a nuclear pacifist. Is that good enough?’ He said yes. That was the only agreement we ever had about my political views.

That’s interesting. Subsequently you’ve become better known for women’s research and for your support of women’s rights. Would you say that these are equally important parts of your life?

That was the case at that time. But the peace movement, it kind of comes in waves. I don’t feel that there’s a peace movement now. I think the women’s movement was fundamentally more democratic. I’m a liberal, I’m a democrat, I want to have equal rights. I don’t think I’m being so unrealistic in my demands. I just think that I’m being rational. But of course that’s how I see myself. Isn’t it?

A portrait of Helga, 1956. Photo: Private archives

Pioneering Gender Quotas

I’ve always felt that it’s important in a democracy for everyone to be equal. And then we also obtained statistics through women’s research. If you look at the first book I wrote, Staten – kvinner ingen adgang? [The State – No Admission for Women?], the statistics made it completely clear. Other feminist researchers found the same thing. And of course there were researchers at Statistics Norway who gave us excellent information about unfair pay differentials between women and men.

And I was also very concerned about teaching positions at universities. I was head of the Gender Equality Committee at the University of Bergen in 1974. I sat on the Committee with the historian Ida Blom and the biochemist Karen Helle, and there was also a very supportive chemistry professor, whose name I can’t now remember.

1975 was the UN’s International Women’s Year, and at that time the issue of women’s equality was on the top of the agenda. The University of Bergen, along with its Rector, was very proud of being the first university to have a Gender Equality Committee. And they asked somebody on a university fellowship. All the others were permanent employees. Not me.

And I became the chair. We came up with gender quotas. That was really the most important thing.

Was it the Committee that launched the term ‘gender quotas’?

Yes. I was personally responsible for coining the phrase. We distinguished between moderate gender quotas and radical gender quotas. The moderate version meant that if two applicants had the same qualifications, then the person appointed would be from the under-represented gender. The radical version was that if there was a woman who was qualified, then she would get the job. I didn’t support radical gender quotas.

But did the Committee also say something about the conditions under which one could contemplate applying moderate gender quotas, and the conditions under which one could legitimately apply radical quotas?

I’m fairly conventional when it comes to academia. I think that the quality criteria are the most important. That has to do with my respect for a university as an institution. But take politics, for example, that’s somewhere I think radical gender quotas are very useful. There were endless discussions about women’s qualifications for political positions. I said that this is a democracy, so this discussion is totally insignificant, it won’t take more than two to three months to get into it. I mean, quite seriously, there were all these men who said that women weren’t qualified. Accordingly, it was important. Because when using a ‘moderate’ quota, the relevance of the qualification was completely central. With ‘radical’ quotas, it was mostly about what gender you were.

This has been very important. I know that you also conceptualized the different justifications for women’s participation as the interests justification, the resources justification, and the social justice justification. Was this something you did in this context, or was this something that came later?

No, it was no doubt because I noticed that we had to supply justifications, even when I thought they weren’t needed. But my opinion is still the same. Today, I think gender equality is generally accepted. But that wasn’t the case then. And of course it also made the situation difficult for women who were not considered qualified. Accordingly, it was important to be strong and to stick to one’s principles. Because at universities the scepticism was deeply entrenched, particularly at the University of Oslo and in the social sciences.

At your 80th birthday celebrations, Hege Skjeie, the first woman to be appointed a professor of political science at the University of Oslo, said to you that she thought Norway was completely unique in its use of gender quotas. That the idea hasn’t become so widespread as perhaps we believe.

No, it hasn’t. Quite simply, it’s still seen as undemocratic. Subsequently, both she and Cathrine Holst [a professor of sociology at the University of Oslo] did much more work on quotas than I ever did. I used the idea most in the first things I wrote, and in politics. But they have written about it.

Do you think gender quotas are an important reason why we have come as far as we have in Norway, for example, in relation to political representation?

Absolutely. But today, women’s political representation is totally accepted. It didn’t take more than five years, so it wasn’t a long and difficult battle. Perhaps it was in some municipalities, if someone had sat there for 30 years and thought it was his right and so on. But I’m thinking of the country as a whole.

But of course there’s a contrast here. Even today we have only limited representation of women at senior levels in business, for example, as you have also pointed out.

Yes. But things are really starting to change now. There’s a huge amount of money in business. Money is an important motivation. Particularly in the lives of men, who could lose these incomes if they got female competition. I’m not saying that women aren’t interested in having money. But for them, it would just be a very pleasant by-product. For men, who to a large extent are the people who have economic control, it would be a significant loss for them to have to share it. And of course, it’s still the case that women in very senior positions in business get a lot of attention in the press, precisely because they are still the exception.

It can’t have been obvious that this Gender Equality Committee at the University of Bergen would turn out to be so significant?

I think it had something to do with the notion that now the time had come. It has to do with the time you are living in and whether society is receptive to change or not.

But someone also has to be the pioneer. It’s clear that you can’t be a pioneer if nothing exists to facilitate your activities.

That’s true. But I was extremely lucky, especially with these men. And Karen Helle was perhaps the most critical voice, because she was professor of biomedicine, her husband, Knut Helle, was professor of history, and she thought it was a bit degrading for women to be appointed because of gender quotas.

But I still believe that feminist research is more important than gender quotas. Absolutely. Gender quotas are just a mechanism.

Cooperation and Conflict in the Women’s Movement

At the start of the 1980s, you proved yourself as a major research entrepreneur by building up a new research project and editing a series of books about women’s living conditions and lives.

Absolutely. In fact, it attracted a lot of attention. One group that was very important for us were women journalists. They could be found at all the newspapers. It was the women journalists who brought things to the public’s attention. In fact, I’ve often emphasized that point.

Was this alliance between civil society and the media of central importance?

Yes. In a way it was also relevant to their own lives. Reidun Kvaale was very important. She was at Aftenposten of course. But there were others as well. We always held launch events for books in the series, and they were always very well attended. Not by researchers, but by women from civil society.

Aftenposten reports Helga’s appointment as Director of Research at the Secretariat for Women and Research at NAVF, 1980. In red, journalist Reidun Kvaale writes a personal note to Helga: ‘Finally!’. Private archives

Women’s organizations attended all the book launches. At that time, they had many more members than they do now. There was an organization called the Housewives’ Association, but of course they have a new name now and the number of members is now 10 percent of what it was. And in fact, I don’t know how much political influence the Norwegian National Women’s Council [Norske Kvinners Nasjonalråd (NKN)], which at that time had 800,000 members, has today. Now there are so many women in workplaces that they can organize in their own workplace. That’s a big difference. It also means that I think that most of the norms I talked about before in relation to universities, they are now accepted by women academics. That quality means something, and so forth. I believe that everything we think is important for good research is accepted by both women and men. That wasn’t necessarily the case in the beginning. In the beginning, there were some non-researchers who thought that qualifications were something that men had invented.

So this was a matter for genuine debate?

Yes, it certainly was. I resigned from the Women’s Front [Kvinnefronten] very quickly. I was actually a ‘founding member’ of the Women’s Front in Norway, along with other members of my women’s group. I was the first to resign, which I did in 1974. The reason was that the major topic at that time was the six-hour working day. The Women’s Front joined with the Socialist Left Party (SV) to oppose a six-hour working day for parents with young children.

For what reason?

That it would discriminate. I asked: ‘What is wrong with limiting it?’ They wanted to have it for the whole population. I said: ‘The whole population? We can’t afford that. You are a taxpayer too. You wouldn’t want your taxes to fund the travels of a 60-year-old man.’ But the opposition was very strong, both within the Women’s Front and also in other organizations. I think it was the Socialist Left Party (SV) – or the Socialist People’s Party, as it was known until 1973 – that was against it. They said it would lead to discrimination in the labour market against parents with young children. They would not get jobs if it was known that their working days would be only six hours long.

In that respect, Margit Glom, for example, was very important. She was at the Union of Commerce and Office Employees (HK). She got the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) on her side. Six-hour days should be for everyone. They shouldn’t be just for parents of young children. But I thought the thing that was realistic and the most necessary was in fact to have it for parents of young children, because those would be important years for their integration into the labour market. I thought it was quite simply irrational to believe that it had to apply to everyone. They called their position principled, but I said it was unrealistic.

But that wasn’t the only reason you resigned, was it?

No. It was the case that when we founded the Women’s Front, it was mostly made up of women on the political left. I remember that I was approached by some right-wing women who asked if they could be involved. I was stupid enough to say: ‘I think perhaps you wouldn’t feel at home.’ That was unkind. It was just stupidity on my part. I remember there was an elderly woman who wanted to be involved, but I said: ‘I think perhaps you won’t feel comfortable.’ So I wasn’t without blame. But really it was just stupidity.

So was this one of the reasons you resigned from the Women’s Front?

Yes, it was really because it was an incredibly authoritarian movement. I’ll just mention one example: that I never got to speak before 1.30 a.m. Or at least extremely late. Some of them, some who are still at the university, have apologized and said that they behaved very badly. They knew that they were behaving badly. But the cause was the most important thing for them. So I travelled to the United States. I was the only one to do so in my women’s group. There were seven of us who resigned, giving our reasons in a letter to the Socialist Left Party and the Women’s Front. I was a member of the Socialist Left Party at that time. And then while I was in the United States, my women’s group wrote a white paper about the authoritarian tendencies in the Women’s Front. That was excellent.

It was mainly to do with the fact that there was a heavy presence from the Workers’ Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist)?

Yes, it was because of the Marxist-Leninists. We called them ‘Pål’s hens’, remember? [Pål Steigan was one of the main leaders of the Workers’ Communist Party.][4] Even today I think there’s some kind of personality trait in people who can be so authoritarian. There’s something or other that I find very unappealing. But the white paper turned out to be excellent.

The Women’s Group: Just Like Family

We must talk about this women’s group that you’re part of. It’s both a political and professional collective that you’ve been involved with almost all your life.

Yes, and it’s also an emotional thing. They are like my sisters.

The Women’s Group. Photo: Private archives

I’ve heard that you even have a ‘family portrait’ of them at home.

Yes, that’s right.

How did that come about?

It was 1975, International Women’s Year, and we gathered in southern Norway. Elisabeth Aasen had a house there, and I came over from the United States. So we celebrated and decided that we should take a photograph. We would all be dressed in white. Long white dresses. And in fact we did the same thing again 10 years later, but then we just wore casual clothes or something a little smarter. That picture isn’t anything special.

So the group was already established in 1970?

Yes, the group existed then. We were all founding members of the Women’s Front. We were Elisabeth Aasen, Jorunn Hareide, Kari Wærness, Kristin Tornes, Sidsel Aamodt Sveen, Kerstin Nordenstam, who is now dead, and then me. In fact, there were also two others, but they left us pretty quickly, because we were too radical for them. All the others were academics and very progressive.

And you’ve become an honorary professor in several places?

Yes, but that’s a different story. I applied for a teaching job at the University of Oslo, which I didn’t get. A member of the appointments committee told me the reason. It wasn’t good. It had nothing to do with my qualifications. It was because my competitor wanted to buy a house, and needed a permanent job in order to get a mortgage.

So the idea was that a man’s role as provider for his family took priority over women’s right to earn a living?

Absolutely. But I’ve always had a very soft spot for the man who got the job. He came into my office the next morning and said: ‘I think I’m really the only person who really understands how you’re feeling. I have a bit of a hunch about how things went. But I just wanted to say that you have my support.’ He was very, very decent. But one of my sayings that I’ve repeated many times is: ‘Thanks to the University of Oslo, I’ve had a very interesting life.’

You’ve certainly had an interesting life, but who should take the credit for it is something we can discuss. It is very generous of you to be grateful for precisely that decision.

Yes, but take Elisabeth Aasen, for example. She has written fantastic books about women through the ages, but she has never been given a university fellowship. They thought she was too popular. Quite unbelievable. But she is very well recognized now.

What has this women’s collective meant for you?

For me, it has been absolutely my most important circle. There is no other group that has been more important for me. It has been incredibly important. For me, because I’d come from abroad, I learned a lot about Norway through the group. It has been a very strong source of support and friendship throughout my whole life. Some of us got divorced, including me, and then being part of a group like this really meant a lot.

So, it has been both a family and professional collective, and a political sounding board.

Politically, it no longer means so much. No doubt they didn’t think my joining the Labour Party was anything to celebrate.

No, it wasn’t a Labour Party group was it?

Not at all. But also it wasn’t so very partisan politically. There was only one person who was furious. She thought it was treachery. I didn’t think so.

The Path to ‘State Feminism’

But back to the book series. We’ve talked a little bit about it. It was something you spent a lot of time on throughout the 1980s and it was important.

When I stood down from the Council for Social Science Research at the Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities (NAVF) – one of the forerunners of the Research Council of Norway – because my term had expired, I was appointed Director of Research at what became the Secretariat for Women’s Research. Hege Skjeie, who had come from the Gender Equality Commission, was head of the Secretariat.[5] And then I was there as Director of Research. So it was me who organized all these meetings we had. The meetings were in groups and themed around certain topics. Many of these books aren’t monographs, but anthologies. In other words, they emerged from the seminars we held, sometimes in mountain hotels, or occasionally in private homes.

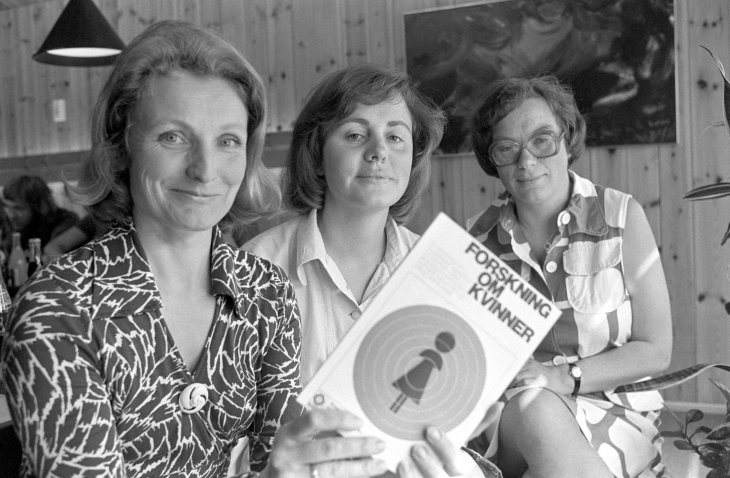

From left: Assistant Professor Helga Hernes, Lecturer Hanne Haavind, and Mari Holmboe Ruge from the Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities (NAVF), working on the study Research on Women in a committee under the Council for Social Science Research, 21 June 1976. Photo: NTB Scanpix

It was Erik Rudeng [historian, publisher, museum director and cultural politician, who in his time worked with Johan Galtung in the field of macro-history] who came up with the idea of a series of books to be published by Scandinavian University Press [Universitetsforlaget]. When he left the publishing house, Dag Gjestland took over, but by then the decision had already been made. As I mentioned, my volume was number two. The first volume was by Kari Wærness and was about social policy. Then, as time went on, there was one after another. But there were never 18 books, as originally planned, there were only 17. I’ve got a slightly bad conscience about that, because there was a group in Trondheim who wanted to do a book about women and work. I said: ‘But good lord, there’s so much about this topic already.’ No doubt I should have been a bit more generous and said yes.

I think you should congratulate yourself for the 17 that were published, rather than blame yourself that the 18th never happened.

Yes, but she was very disappointed and I understand that. But it was in connection with this series that women journalists were so important. Because the books got discussed. The books got discussed for their own sakes, and the simple fact that a series was being published was referred to as a sensation.

My academic council at the NAVF was B, which was for the social sciences, while academic council A was for the humanities. We always said that A had only the elitists, because they gave fellowships to just a few women. My dear friend Jorunn Hareide had such a fellowship for four years. I think that all those awarded fellowships by Council A went on to become professors. The chair there was Anne-Lise Hilmen, while Mari Holmboe Ruge was chair for the social sciences.

Mari and Hanne Haavind wrote a report for the Social Sciences Research Council, and it was Mari who took the initiative.[6] It was Hanne who headed the group that wrote this report and they proposed a secretariat. In any event, they proposed a more collective solution whereby one rather gave funding to meetings, and help for publications. I don’t think we ever granted funding for short-term fellowships. There were obviously some people who were awarded fellowships on ordinary competitive grounds, but it was mainly a more collective way of creating a new academic field. There were sociologists, political scientists. There weren’t so many female political scientists, I think there were three of us. Many anthropologists, some economists. There was a pretty good breadth. We would have liked to have had a really good book on economics. Harriet Holter, a social psychologist who played a central role in women’s research, was someone we didn’t include, but the social anthropologist Ingrid Rudie made one of the major anthologies. There were three major anthologies. But I’ve never actually looked into how many of these books became required reading. That would be interesting.

But your book on state feminism is still required reading?

Yes, I believe so. As I explained earlier, the process of coming up with the term state feminism took 10 seconds. It happened when Rune Slagstad, the editor for the book series, phoned me. I was sitting at the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study (SCAS) in Uppsala, where I’d been awarded a fellowship. I was a member of the Swedish study of power and democracy. ‘Helga,’ he said. ‘I must have the title of these two books, yours and Tove’s [Stang Dahl], tomorrow. What’s your title?’ And I simply said: ‘It must have something to do with power… I’d suggest Women and Power: Essays in State Feminism.’ So it took 10 seconds.

But now it’s become a key concept, hasn’t it?

That happened while I was abroad serving as an ambassador. I’d been ambassador in two countries, first in Vienna [with dual accreditation to Bratislava and Vienna-based international organizations], and then in Bern [with dual accreditation to the Vatican]. And suddenly state feminism had become an important concept. I wasn’t responsible for doing that. Of course it was many years later. I think that’s actually very interesting.

Hege Skjeie called the term a stroke of genius.

Yes. It was a stroke of genius, but a very instinctive one.

But it captured your ideas?

Yes, it captured my ideas completely. I said: ‘We should be grateful that we have a state that is as feminist as it is.’ I still believe that, despite the fact that some people don’t think it’s good enough. I’ve always been very positive. And it has been said that I’m too positive. But this concept [state feminism] became established by people other than me.

Was the phrase adopted immediately in the Norwegian debate?

No. I first noticed it when I came back from being ambassador in Switzerland. People were talking about state feminism.

Helga meeting Pope John Paul II, ca. 2003. Photo: Ambassador based in Bern, accredited to the Vatican state

State Feminism Goes Global

This subject of state feminism is interesting, but why did it reappear on the agenda in the early 2000s?

I don’t know. I must confess that I don’t know. But it was certainly the case that even some politicians began to use the term in a positive manner. I believe I called myself a feminist, but that wasn’t so usual. One said that one was a female advocate for women’s rights. As I mentioned earlier, I was invited to meetings, mainly by the Labour Party, because Britt Schultz [Labour politician and later State Secretary in the prime minister’s office] was head of the women’s movement there, but also by the other parties. I always said yes. But I don’t think that I used the term state feminism. It would actually be interesting to find out how the term made a breakthrough. I was simply struck that it had happened. In fact, I don’t know if I got credit for the term in the beginning. Of course, the term is the secondary title of my book Women and Power: Essays in State Feminism. I was the person who coined the term. It was becoming more commonly used from the mid-1990s, but the actual book came out in 1987.

So, it just turned up so much later? That’s interesting.

Yes, it is. But I continue to think that it’s a good concept. Because I still think that regardless of whether people believe that the Labour Party is reactionary, it is Labour that has got this through, and also the Confederation of Trade Unions (LO). This idea that women should have equal pay. I remember how I pestered Jens Stoltenberg [leader of the Worker’s Youth Leage, AUF – the youth association of Norway’s Labour Party – from 1985 to 89] in particular, and others too. I got on their nerves. But it didn’t matter to me. And I also had good friends in the trade union movement. Esther Kostøl was very supportive. I’d actually written some rather stinging criticism. In the feminist magazine Kjerringråd, I’d written: ‘The Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions is really the Norwegian Men’s Confederation.’

If we take the women’s movement a little further forward to the beginning of this millennium and United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security, there are some who claim that the fundamental idea of the concept of state feminism pervades this resolution. Do you see it like that?

But that’s how it is!

Hege Skjeie, for example, suggested this. And Torunn Tryggestad [PRIO’s Deputy Director and Director of the PRIO Centre on Gender, Peace and Security] is interested in the same suggestion.

Yes, and actually I think she’s correct. But it is understandable, because this is a UN resolution. UN resolutions are addressed to the Member States, not to civil society. And of course feminism as a whole was only partially directed towards public authorities. In general, the Norwegian women’s research was more about strengthening the women’s movement. But a UN resolution is of course directed at the Member States. And that is why one can call it state feminism. I haven’t thought about it. I’ve tried to look a little in the archives at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but I haven’t really got very far.

No, but to the extent it resonates with the process behind Norwegian state feminism, which is about both the bottom-up work of civil society and the government’s response, there is a parallel. This parallel could perhaps not have occurred until after the end of the Cold War. It was in the 1990s that we got a more open UN system that was receptive to civil society activism.

The continent where a women’s peace movement was most active was Africa. But they didn’t call it state feminism. They called it women’s rights. But they addressed themselves to their own governments and to the international community. You had these international women’s years with major conferences in Mexico City in 1975, Copenhagen in 1980, Nairobi in 1985, and finally Beijing in 1995. But you won’t find the term state feminism anywhere. You might well say, as Hege said, that the spirit of the resolution reflects the same concept, because it addresses civil society only to a limited extent, and devotes most of its content to states and their obligations. But even so, the resolution has mobilized women. When I came home, after having been in Switzerland, I met up with Torunn Tryggestad and Kari Karamé. Obviously, they thought that I knew what Resolution 1325 was, but I had no idea.

It didn’t attract such great attention that you, as a Head of Station at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, noticed it? Even with your special interest in the topic?

No, not at all. Never. So I think that came later. There’s nothing wrong with that.

I’ve also had the impression that it took 10 years before the resolution began to gather some momentum.

Yes. Torunn and Inger Skjelsbæk write about that. I’ve tried to learn what happened in Mexico City, Copenhagen, Nairobi and Beijing. I was only actually present at the meeting in Copenhagen, and in that meeting, there was nothing at all that had any suggestion of state feminism. I feel the meeting was really more directed towards civil society. Because there weren’t so many UN countries that thought that this was particularly interesting. The Norwegian government, you know they decided to support the Mexico conference in 1975. I think they gave NOK 650,000 altogether, but that wasn’t much, compared to other priority areas.

Helga Hernes, State Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, May 1988. Photo: NTB Scanpix/Aage Storløkken, VG

Isn’t this rather similar to what you and your colleagues achieved in a Norwegian context with a relatively strong mobilization of civil society and heavyweight institutions where there are many potential agents for change that one can build alliances with, and then these agents use their influence to set an agenda and establish fora to invite civil society to join as a facilitator to change the institutions?

Yes, I think that’s completely right. Karin Stoltenberg [Director General at the Ministry of Children and Family Affairs] arranged these matters from the ministry, and I remember that once I asked very cautiously if I could have a place on the Norwegian delegation. ‘I don’t know what you would have to do there,’ said Karin. ‘Well Karin, I have actually worked on women’s issues for quite a few years.’ ‘Yes, but this isn’t to do with that. This is mostly for us within the ministries.’ I think that sometimes she would rather have had me than Janne Haaland Matlary [Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo], who became a member of the papal delegation and tried her utmost to influence the Norwegian delegation. She is anti-abortion and a very, very strict Catholic. So then I would no doubt have been more amenable.

Hege Skjeie went even further than that. She said that she recognized Helga Hernes in much of 1325.

Yes, but that is because the resolution is universal. This is today’s food for thought. This is the strength of the small countries. In the French, German or British foreign ministries, someone like me would never have had any chance at all. But with the Norwegian ministry, I can phone and say: ‘Can we meet for coffee?’ Small countries are completely different in their decision-making structures. They provide possibilities for different groups to exert influence. I think it has to do with this much greater wealth of ideas that often exists in small countries. If you look at which countries ally themselves with each other, it’s usually the small countries. It’s very rare that you see Germany united with Finland, Sweden, Denmark and so on. The United Kingdom, now and then. And of course Canada. Canada is the only large country where one sees that women’s issues get aired in international fora. Not the only country, but I think the most obvious.

Small countries are completely different in their decision-making structures. They provide possibilities for different groups to exert influence. […] In the French, German or British foreign ministries, someone like me would never have had any chance at all. But with the Norwegian ministry, I can phone and say: ‘Can we meet for coffee?’

A German Child During and After the War

Something we have not talked much about is the early part of your life, your childhood.[7] How has it influenced your interests later on? It seems to have been a pretty dramatic period.

Yes, but you know, I was in the Catholic church recently, and I’ll now say something that I think is also said by psychologists and psychiatrists, that as a child, so long as you have a person you can rely on – and for me it was my grandmother – you will feel secure. I saw my grandmother when they tried to shoot my grandfather. He was a general and fled to the West in May 1945, just like my father. We other family members had already fled in February. And we lived in real poverty up in the mountains. My grandfather had big problems with his gall bladder. But he found us. And then someone in the village told the Americans that a general was here. And so two American soldiers arrived. They asked: ‘Where is the general?’, pointing their guns and so on. My grandmother said: ‘Well, if you’re interested in this sick old man, that’s him.’ ‘You have to come with us,’ they said, and they took him. He was very sick. They were only interested in taking him.

Then one of them said: ‘Why don’t we just shoot him down? He is going to be shot anyway.’ They didn’t know my grandmother was an American. She said: ‘Who the hell do you think you are? You look like you are from Alabama, and in Alabama they don’t even know what shoes are. You probably got your first pair of shoes when you got into the army. What are you doing with this old man? Why do you want to shoot an old man? What has he done to you?’ These two young soldiers were completely freaked out.

He was taken to an American hospital and was imprisoned there for three years. He was operated on three times for his gall bladder problem. I visited him many times. Just think: he wouldn’t have survived if he hadn’t been imprisoned. But I was frightened that time when they came into that room in the mountains with their weapons. I thought they would shoot us, but they didn’t want to. They only wanted to shoot him.

That’s not an experience that we’ve all had during our childhoods.

No. We lived by the Baltic in Kolberg, which is now in Poland. We spent a lot of time in the air-raid shelter from about November 1944 until we fled in February 1945. Often it was only during the night, but sometimes also during the day. Mostly we were being bombed by the British. It was my uncle who helped us to decide when we should flee and how we should seek refuge.

So we sat on a train outside Dresden for five days while it was being bombed. It was terrible to hear the bombing. The sky was dark red. But we weren’t bombed. Our train wasn’t bombed. So we actually got down to Vienna, and when we got to Vienna, the Russians arrived. Then my grandfather arranged for a truck that took us and some other families, and we ended up in a very idyllic valley close to Zell am See. So there we were. We arrived there, I think it must have been in April/May, and then we stayed there.

So then there was a decision on the Austrian side that all Reichsdeutsche [‘Imperial Germans’] – of course we were Reichsdeutsche, while the Austrians and all the other German speakers were so-called Volksdeutsche [‘German folk’] — had to leave Austria within three days. Then we had help from our young American friends. All of them fell for my wonderful grandmother, so in August 1945, we were driven with three other families to Chiemsee, an extremely beautiful place where one of my aunts had some friends. That was where I grew up. We didn’t have much, just our clothes.

Chiemsee is between Munich and Salzburg, closer to Salzburg. It’s one of the most beautiful… It’s a large lake where King Ludwig II of Bavaria built a castle. That’s where we arrived. We started to attend school and that’s where I took my final school exams. My brother still lives there with his family. My only sister lives there. It was completely incredible. My mother became a doctor at various hospitals, but spent the last 15 years of her life at her home there. And my grandparents were there too.

I don’t know how much you know about German history, but Prussia isn’t exactly a place that most Germans are so very fond of, and in Bavaria they simply called us Saupreussen [‘pig Prussians’]. But I wasn’t bullied as much as my younger siblings, so I always had to protect them. I don’t know why, but I think I was just used to being the eldest. We had a long journey to school, so this wasn’t always easy. My grandmother was also a peacemaker. Initially, we were put up in a guest house, and the people living there were clearly not particularly happy for us to be billeted there, you know, having refugees in their house. But we are still friends with them. That is thanks to my grandmother, who became best friends with their grandmother.

Helga Hernes with her three siblings upon arriving to Bavaria as refugees of the war, 1945. Photo: Private archives

And so you all had to establish a completely new life there?

Kind of. When my mother became a doctor at Augsburg, 150 kilometres from Chiemsee, it meant she had to commute. She came home every weekend. So it was grandmother who brought us up, and we always had a nanny. After a year, my father suddenly arrived home on foot. He had been in France as a prisoner of the Americans. My grandfather was imprisoned for three years. But really that went relatively uneventfully. Then we moved to Augsburg. But I managed to move back to live with my grandmother.

You know, my father, because he had been an officer, was not permitted to continue his legal studies. He had studied law for four semesters, but now he had to start working with all kinds of commercial activities, mostly bartering.

I think probably his life would have been better if he had been permitted to finish his legal studies. It was always my mother, who was a doctor, who was the main breadwinner. But the Americans were a very positive occupying power. There was very little violence, I have to say. At any rate, I can’t remember it. And now we were living in the country. I lived happily in Augsburg for three years, and went to a school for girls. I was confirmed there. My mother was active in city politics for the Free Democratic Party.

But you say that the Americans were a positive occupying power?

Yes, and of course they hadn’t experienced attacks during the war. The British had suffered much more during the war, so the British weren’t particularly friendly to the Germans, they had no empathy. And the British didn’t have much food either. We did go hungry. For the first year, I remember very well that I went to bed hungry every night. But you get used to it. I remember that I got a single one-centimetre-thick slice of bread each day, and also we sometimes made a little pea soup. The farmers helped us – of course you’re a farmer too, Kristian – to get some potatoes planted. So, by doing so, we also had potatoes during the winter. I don’t know how I should describe it. That was our life. It wasn’t something you needed to be very scared of. You were hungry and you didn’t have any fine clothes, and if you needed a pair of shoes, it was a family catastrophe. We wore wooden clogs. We were really poor. But of course we weren’t the only ones.

But there was a long period towards the end of the war when you must have been pretty anxious and felt the lack of security. You say that it’s important to have an adult that one trusts, and I think so too.

Absolutely. My grandmother, what I’ve told you about her, that was only the most dramatic incident. Otherwise, she was a woman who was very caring and must also have been pretty overworked. But we always had at least one maid. And usually we also had someone who came in to do the cleaning. But of course we were living in this guest house, where the owners really wanted to use the rooms for other purposes. So, as refugees, you weren’t exactly popular.

I well remember that at one point I had a Bavarian boyfriend. That was a big problem. I was 15 or 16 years old, and his mother was extremely worried that it would get serious. My grandmother had seven grandchildren, and one of them had a nanny who fell in love with a Bavarian. They had to wait 10 years before they were allowed to marry. So as you can imagine, we weren’t well thought of. We were refugee children.

But subsequently you’ve said that you don’t feel any bitterness that Germany was treated as it was, that you feel it got what it deserved, in a way?

I wouldn’t say that we were starving. They were difficult times, but that was the result of the war.

Is that what you’re thinking when you say that Germany got what it deserved?

At least two or three years passed after the war before I understood what concentration camps were. I asked my grandmother, who just said: ‘That’s where people go who have done something wrong.’ And I said: ‘I thought they went to prison.’ ‘Yes, but when there are many of them, then they have to end up in a camp.’ It wasn’t discussed. History teaching, if you were lucky with your teacher, went up to 1918, but most teachers stopped at 1870. No one ever said anything at all about the Third Reich. No history teachers. No German teachers. No one. It was totally…

There was a complete lid on contemporary history?

When I think back on it, it’s still incomprehensible. I heard the men in the guest house, they talked about their wartime experiences, but I never noticed any suggestion of guilt. That emerged first in the next generation, in the 1960s and 70s. But at that point, I wasn’t in Germany. It was the generation of 1968 who lifted the lid. That was really very late.

Academia and Activism in 1960s America

And the 1968 protest movement was something you were a part of, just on another continent.

Yes, I was on another continent. But obviously, the anti-Vietnam War movement was very international. I remember that when I was working in Boston, we often travelled down to the demonstrations. I heard Martin Luther King. My students came too. I didn’t take them with me, but they came of their own accord. Even though I was teaching at a very radical and liberal school, even they wouldn’t want me to …

To be leading protests in Washington DC?

I was very lucky that in 1961 I got to participate in the civil rights movement. […] [W]e travelled to Ralph David Abernathy Sr.’s headquarters. We spent time with Abernathy. Martin Luther King was his second-in-command. We travelled to Selma, Alabama.

No, and I think that was completely right. Sometimes, I talked about the Vietnam War in history lessons, and then I got told I shouldn’t do that. And there was also the civil rights movement. For America as a country, the civil rights movement was actually much more important than the protests against the Vietnam War. The anti-Vietnam War movement had only one message for the government: ‘Get out of there.’ There was nothing else.

I was very lucky that in 1961 I got to participate in the civil rights movement. We formed a group called Ambassadors for Friendship. We were four foreigners and a young American woman. And there was a car dealer who was enthusiastic about our group. He gave us a huge station wagon, and we painted Ambassadors for Friendship on it. We followed a big U-shaped route through the whole United States.

Helga Hernes with other members of the activist group, Ambassadors for Friendship, participating in the US civil rights movement, 1960. Photo: Private archives

So this was students from Mount Holyoke?

Yes. For example, we travelled to Ralph David Abernathy Sr.’s headquarters. We spent time with Abernathy. Martin Luther King was his second-in-command. We travelled to Selma, Alabama.

During the actual march?

Yes. We were very, very involved in activism. Then we travelled to Texas, where they found out who we were: ‘Socialists. We don’t like Socialists!’. We weren’t socialists, but whatever. We followed a so-called U-shaped route through the whole United States. All the Southern states. Alabama, Mississippi. But it was interesting. We were often invited to visit churches. I was even told: ‘Girl, you should have been a preacher!’ We talked about peace and reconciliation. We also had a young American woman with us. She was fearless about asking for help, and we got masses of help. It was very, very interesting.

It’s easy to see a thread here from your childhood, your experience of war and what it meant for you and your family. When do you think that you first saw how one could work politically to achieve peace? Was it in the United States? Or did you already see elements of it while you were a teenager in Germany?

Not in Germany, no. I was very happy to get out of Germany. I thought it was quite simply unpleasant and embarrassing that we could never talk about anything.

Exactly. So you became concerned about it very early?

Yes. I remember one time I came back from the United States. That was the only time I had a really heated confrontation with my grandparents, so much so that they nearly threw me out. You know who Arthur Miller was? He had written a play which was about anti-Semitism. The play was shown on German television. My grandfather, who was a TV addict, watched the play and was completely outraged. I began to scream at him: ‘What is it you’re saying? What is it you’re saying?’ And my grandmother just came in and took me outside: ‘If you ever mention that subject again, then you can’t stay with us.’

I had other friends who were also not allowed to talk about how the Jews had been persecuted, who weren’t allowed to mention Hitler at all. So it was a very strong taboo, and I’m sure that the man who was headmaster at my school was a Nazi. But what was interesting was that none of us ever felt any empathy or sympathy with what had happened in Germany. All of us thought it was completely appalling. And then the Americans, they had what were known as America Houses. That was something that my family didn’t like, but I snuck my way there. There I saw movies. It [the house] was very important. An important institution.

So you loved America from an early age?

Yes, yes, yes, I loved America. Also because of my grandmother. In spite of it all, she was an American opera singer. But I do say that the Americans took a very naive approach to democratizing Germany. Their approach was very proper. The most sentimental movies and I don’t know what else. But I think the Americans did a very, very good job when they arrived as an occupying power. It must have been terrible to have been in the French zone, or obviously in the Russian zone. Quite terrible because people didn’t get food, and if they weren’t Communists they were treated very badly. But the British and the French, they had of course undergone their own very powerful experiences.

Helga Hernes in her youth, ca. 1952. Photo: Private archives

The Americans had a completely different starting point, even though they had also lost a relatively large number of young soldiers. But even so, they thought it was exciting to be in a different country, and they were just a different type of person. They brought their music. It was completely fantastic. I don’t know if you’ve read Year Zero by Ian Buruma [Penguin 2013]. The thing that really liberated the Germans and got them to love the Americans was the music. It was everywhere. There was almost no criminality, and unfortunately I have to say that Black Americans were responsible for the small amount of criminality that did occur. To them we were well-to-do. I sound a bit as though I’m very unrealistic, but I don’t think that I am.

No. You’ve experienced it.

Yes. For them ‘it was a trip to Europe’.

What do you think have been your most important sources of inspiration professionally? Now I’m thinking of your whole lifetime, right back to when you travelled to the United States, perhaps even earlier.

Yes, I must say I was very lucky with the schools I attended in the United States. I got my AFS scholarship, and ended up at a Quaker high school in Baltimore, the Friends School of Baltimore. I entered a whole new world. Both because they were Quakers and because so many were Jewish. They just accepted me. Even though it was only 1956. No one ever said anything about my being German or anything like that. I had Jewish friends. So for me, who came from Germany and had been ashamed of what Germany had done, it was quite incredible. So I got a scholarship, and was lucky enough to go to a Quaker school. I still think that the Quakers have an incredible way of looking at life. I travelled back home because I wanted to get my high school diploma in Germany. At that time, I thought that was very important.

I spent one year in Baltimore. It really meant a lot. They gave me a high school diploma after that one year. So actually I was qualified. I really wanted to go back to Germany to get my German high school diploma, and that’s what I did. Then I applied to Mount Holyoke. But I didn’t apply only to Mount Holyoke. My American mother, who was a fantastic woman, I think sent 30 letters to different colleges about this brilliant… Well, you know what Americans are like.

I got three scholarships from top-ranking colleges. But of course the best was Mount Holyoke, the oldest women’s college, founded in 1837. I was there for two years and gained a BA in political science. With a BA from Mount Holyoke, you’re seen as a member of the elite. They [the women’s colleges] are the Seven Sisters. Every evening we sang ‘Oh, Mount Holyoke, we pay thee devotion’. It was very, very fine. And then I became a teacher. This was at a very radical, advanced school outside Cambridge, Massachusetts. I got a job as a teacher there because I still had my boyfriend. I was doing what was known as PHT – Putting Husband Through. You earn the money while he studies. This worked really well because I got to be at one of those very radical schools dating from the 1930s. It had a very good reputation. I was a house mother, and I also taught German and history.

This was also the time when the Vietnam War was at its height. So I was very active in the anti-war movement. Then I applied to Johns Hopkins and got in there. There I studied both political science and international policy and wrote my doctorate on the international community. And then I came to Norway. I was very fortunate with all the schools I attended. All of them: college, high school, my teachers, and graduate school. You had a library where you could stay until midnight. Of course, that made a big impression on me. I’ve always been grateful. I could never have done that in Germany. You wouldn’t have had that quality, or that student life. Nor did you have that kind of organization. Everything is much more left to the individual, while in the United States, if you attend an elite institution, you get followed up.

In fact, I think that created a foundation that helped me when I came to Bergen and taught there. That I knew what a good university was. I was in Comparative Politics, but the department was called the Department of Sociology, and at least half of the students had been in the United States.

And they had brought a culture with them?

Yes, very much so. And also Stein Rokkan was quite marvellous because he was so international and he took me all over the place. He was very generous.

Politician and Diplomat

I want to ask you a little about your career as a civil servant and as a politician. Because it’s interesting: you came from a background that was actually very involved in activism. Some would perhaps describe you as a pragmatic activist, in the sense that you have been results-oriented. You have very clearly stuck to your principles as an activist. And then you entered a political service where it’s necessary to compromise to a much greater extent and even perhaps implement or convey messages for which you don’t necessarily have much personal sympathy. Has it been difficult?

Actually it hasn’t. I don’t actually know how often, with the exception of this ghastly whale business, where I had to travel around Europe and it was really awful. Otherwise, I haven’t had to convey messages that weren’t welcomed by the recipient.

I wasn’t an opponent of NATO. I wasn’t a pacifist. That’s pretty much the only thing I can imagine that would have caused difficulties for me at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

But weren’t you a nuclear pacifist?

Yes, and I think several of us were. And so I don’t think that was a problem either. For that reason, NATO’s dual-track decision was a major problem, as we’ve spoken about already. I think it shows Thorvald Stoltenberg’s high-mindedness that he took me into the fold.

I once saw an article that Rune Slagstad had written about me, where he quoted from a conversation with Thorvald, who said: ‘She’s very different from me, and that’s why I chose her.’[8] That’s actually not correct. He was a mixture of very naive and very tough. He had two sides. But he was unbelievably knowledgeable. He had a phenomenal memory. He remembered everything.

But I’m trying to think back to situations which weren’t really so… I really can’t remember. I went on trips to Africa with Knut Vollebæk. Those were purely positive. I had been on tours of Asia, but there it was really only the Japanese who had an understanding for our point of view. The other Asian states had a completely different context for the decisions they took after the war in relation to defence policy. But it was good that we could live with each other in the northern regions without shooting at each other. I’m trying now to remember my travels abroad. I don’t really remember anything unpleasant. But perhaps I’ve just suppressed the memory. I don’t think so, but I don’t know.

But you became a key defender of Norwegian whaling policy for a while?

Yes. I thought that was appalling. I went to Thorvald. He got so angry with me that he threw me out of his office. That was because he said: ‘Helga, I’ve asked once before. You know that Gro wants it this way.’ I’m certain that he thought it was a load of nonsense. But he was really angry with me. Genuinely angry. Such that I burst into tears and ran out of the office. The press spokesman arrived. He’d heard what had happened, and comforted me. That was the only time something unpleasant happened. But it was because I didn’t want to go along with it. I thought it was stupid.

You thought it was wrong?

I thought it was wrong. I thought it damaged Norway’s reputation. I had to travel to all these countries and defend our whaling policy, which I thought damaged Norway’s reputation, and be told: ‘Have you completely lost your mind?’ Whales are treated almost as holy creatures by some people. Particularly by American ambassadors to Norway. There was a woman, Ambassador Loret Miller Ruppe, she came all the time and harangued us.

It was entirely possible to be a nuclear pacifist. The battle against the dual-track decision happened long before I entered the corridors of power. Thorvald knew about it. Thorvald knew that I was a nuclear pacifist, but he thought that was a good thing. He didn’t have anything against it. He said: ‘The more vision we show, Helga, the better it will be for us.’ I had an incredible amount of freedom. In fact, I only rarely had to clear things with him. Only rarely.

But also we didn’t have any major problems, apart from this stupid whaling business. He took me in despite the fact that I’d been very active in campaigning against the dual-track decision. I was interviewed by many newspapers, and twice I was on television. Do you remember the TV programme På sparket [Off the cuff]?

Yes.

The Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) researcher Martin Sæter and I were up against Johan Jørgen Holst and Arne Olav Brundtland, also from NUPI. While the camera was on me, they always sat there laughing and so on, trying to make me lose my temper. It was the first time I’d ever been on television. They really exploited that to the maximum, but I kept my cool.

That’s almost a parody of a domination strategy.

Yes, absolutely. But afterwards Martin Sæter described me as a saint. But you know, Johan Jørgen also wanted to have me as his State Secretary. In fact, I’ve got no idea whether he was a nuclear pacifist or not. I think he was simply ambitious, I don’t know. I was only interested in working with Thorvald because he and I could speak openly to each other. He was the boss.

Helga Hernes as State Secretary in the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1988–1989; 1990–1993). Photo: Private archives

Then the whole Middle East process occurred without me actually knowing about it. We were free to walk into Thorvald’s office at any time. When it was getting a bit late one evening, I went into his office to say goodnight, and he was sitting there whispering with Jan Egeland. I had no idea what was going on, just laughter and high spirits and so on. ‘Goodnight, we’re also going home.’ I didn’t get to know about it until things were pretty far along.

Then Jan Egeland turned up and told me about it. I had a kind of double door in my office. We always used to go in there. There was no one in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who knew about it apart from Jan and Thorvald. He took me into this little nook and whispered to me: ‘Helga, I think we’ve had a breakthrough. I think this is going to work out.’

I’ve talked to your American colleague at that time, Ed Djerejian, who is now head of the Baker Center at Rice University in Texas. A very interesting man. He had the Middle East portfolio during his time as undersecretary. He also didn’t know what was going on. But he told me that they had picked up some signals about something going on in Oslo, that they had actually tried to make a thorough investigation.

Actually, I think it was quite right that I didn’t know what was going on, because I had no role in it. The only role I had was to protect Mona Juul. Because at some point or other Mona got involved, and then she became somewhat unwell. Then I simply had to say to her sometimes: ‘Now you must go home and go to bed.’ I knew that she was sometimes absent for several days. She was my allotted task. If she had been at another office, then her boss would have wondered what she was up to. While I was simply told: ‘Mona will be working for you, but she will also be working with other things.’ But that was Jan’s business, and obviously Thorvald’s. But Thorvald was certainly a bit upset about having to step down in 1993 and hand over the job of foreign minister to Johan Jørgen.

It was Thorvald who had started the process. Thorvald was cunning. He loved it that I called him cunning. Johan Jørgen wasn’t as generous as Thorvald. He didn’t have that kind of personality. I remember that Terje Rød-Larsen sometimes got furious with him because he was so indiscreet.

The whole Middle East process occurred without me actually knowing about it. […] Then Jan Egeland turned up and told me about it. […] There was no one in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who knew about it apart from Jan and Thorvald [Stoltenberg]. He took me into this little nook and whispered to me: ‘Helga, I think we’ve had a breakthrough. I think this is going to work out.’

Overseeing the Secret Services

You were also Chair of the parliamentary Intelligence Oversight Committee (commonly known as the EOS Committee). Wasn’t it a historic occurrence for someone to be simultaneously a senior researcher at PRIO and Chair of the EOS Committee?

Yes, but it was also because of Stein Tønnesson [Director of PRIO 2001–2009] that I stopped.

Stein said to me: ‘Helga, I don’t like it. I just want you to know how I think. I don’t like the secret services.’ I simply said: ‘I like the secret services, but I hear what you’re saying.’ The secret services are important.

So you only served [on the committee] for a limited period because of this?

Yes. I resigned. That was the choice I made. In fact, the Secretary General of the Norwegian Parliament [Stortinget] offered me a pretty high salary to stay. I’ve never been sorry about it. Because it gets rather monotonous after a while.

You don’t really find much out. It’s not so difficult for them to shut you out if they want to. But I did gain great respect for the Intelligence Service. And not really so much respect for the Norwegian Police Security Service (PST). So that was very interesting. But I had total respect for what Stein said to me. He didn’t tell me that I had to stand down. I thought about it, and then I thought that really he was right. What was I doing at a peace research institute and spending masses of time going through files that were… ? It wasn’t exactly a ‘sexy job’.

Stein [Tønnesson] said to me: ‘Helga, I don’t like it. I just want you to know how I think. I don’t like the secret services.’ I simply said: ‘I like the secret services, but I hear what you’re saying’. […] I understood very well that what Stein said to me was a personal opinion. It wasn’t as though he had put a pistol to my chest and said I had to choose.

Yes, I can certainly understand that there’s a lot that’s very routine. To some extent this is really a function whose existence is its most important characteristic. Partly it covers the backs of the secret services, and partly it ensures that people don’t step over certain boundaries, because they know that someone is keeping an eye on them. It’s important.

Yes. In fact, you have to be very good to do this job well. We had at least two very good lawyers. Although one of them died. It’s almost essential to be a lawyer, because there’s something about the legal method. I learned a lot from Trygve Harvold. I think that when one gets these kinds of jobs that are so important and so complicated, people actually don’t understand how complicated they are. The Intelligence Service could have sent us around in circles if they’d wanted to, but they didn’t. They behaved properly.

I was a bit surprised when Stein said that to me, because I thought it was kind of salon radicalism. And then I thought that actually he was right. I thought that he didn’t like it because a radical-democratic institute wouldn’t value the secret services. In any case, there was no doubt. I had no doubt what I preferred. The only thing was that I would have liked to have earned more money.

But did you yourself think that there was a tension there? A tension between what you did at PRIO and performing a role such as Chair of the EOS Committee?

No, I actually don’t think so. Given that I’ve seen how this institute has a very broad agenda, I can’t actually see that there was any incongruity or conflict of interest.

It was something that had to be built up when I arrived. Because it had been one of my former colleagues from the foreign ministry, who really hadn’t… But the secretariat grew a lot under me. Very capable lawyers. I gained a huge amount of respect for these young people. I learned a lot. And then, as already mentioned, there were at least two members of the Committee who had some grasp of the work. After a while, I also began to get some grasp of the work. It’s a very demanding role. I understood very well that what Stein said to me was a personal opinion. It wasn’t as though he had put a pistol to my chest and said I had to choose. He didn’t do that. He just said: ‘You know that I don’t like it.’

Back to the Academy: Gender and Peace Research

Yes, perhaps it’s natural to go from here to how your interest in women’s research led you to PRIO in 2006?

Yes, it led me. Or really, I was dragged. Thank God! It was a real stroke of luck for me. Inger Skjelsbæk got in touch with me. Then Inger and I, both of us, saw that we must have Torunn Tryggestad. I didn’t know Torunn particularly well, but I was slightly acquainted with her. So I invited Torunn to come to my apartment for a chat. Of course, she did have very close contact with Inger.[9]

Torunn L. Tryggestad, Helga Hernes and Inger Skjelsbæk at the Launch of the Nordic Women Mediators’ Network, 2015. Photo: Julie Lunde Lillesæter/Differ Media

You say that you were dragged to PRIO, but that doesn’t really mean that you were dragged there against your will?

Not at all. I was over the moon. Firstly because they wanted to build up the women’s perspective, and that was something I wanted too. I had always said, especially to [the sociologist] Tove Stang Dahl, who unfortunately died in 1993, that the thing that was wrong with women’s research in Norway, in which I had played a fairly central role, was that we were too nationally oriented. We needed to be more international. She said: ‘But Helga, what do you mean?’ She thought that my using the word ‘state’ in the title of a book was already a step too far, that I was too complicit. I saw this as an opportunity to fulfil an old dream, which was to internationalize Norwegian women’s research.

So I had these two fantastic young women who supported this, and who were also interested in it. They were both confident, knowledgeable, energetic. I mean, what else could one want? So for me, it was utterly fantastic. Because I had left Switzerland two years early because it was so boring that I thought I would die. But at any rate, you’re asking me why I think this was utterly fantastic. I didn’t know much about PRIO. But I’d been here once in 1969, and so I did know some people here.

Torunn has a wonderful talent for obtaining funding. I always thought that I was the best, but she surpasses me. People at the ministries were always laughing: ‘Helga has arrived in her silver outfit, so she must want money.’

You had a special outfit for this purpose?

No. A woman at the OED [Ministry of Petroleum and Energy] said it one time, and I said: ‘But I’ve never – the OED?’ ‘Yes, but of course I know about you.’ Well, but as I have already mentioned, I always come back to the fact that having allies in the central government bureaucracy is very important. But the Max Planck Institute [in Germany], of course that’s a national institution. They have their own funding, but they also get public money. So it’s not only in small countries, but on the whole it’s in smaller countries, that you get access to funds for professional renewal.

After I finished my doctoral thesis, that was actually one of the things I regretted. The only regret I have in relation to my academic life is that Stein Rokkan did not allow me to do research on international policy. He said: ‘Helga, I’ve promised the University of Oslo that we won’t get involved in that, and so you must simply…’. And so for me this was an old dream. Internationalizing women’s research. And I think it was one that was shared by Inger. We actually didn’t have much knowledge about violence against women. I’d met Torunn in South Africa, and she had obtained funding from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to work with peacekeeping forces.

Torunn [Tryggestad] has a wonderful talent for obtaining funding. I always thought that I was the best, but she surpasses me. People at the ministries were always laughing: ‘Helga has arrived in her silver outfit, so she must want money.’

The Training for Peace project?

Yes. Training for Peace. For me it was pure heaven. That I could suddenly begin to think about women’s issues internationally. I mean it wasn’t difficult to convince me. I was very happy. There can never be any doubt that I thought of the offer from PRIO as a gift.

The Norwegian National Action Plan on 1325 that you helped to write, was it the first?

That was Steffen Kongstad at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. That was him. He was a friend and a good supporter. And it was really extremely important. The Action Plans that came later were of course even better. But the first was the most important. That it was published at all. It was difficult to get the attention of the political leadership, but that didn’t actually matter so much, because there’s an awful lot that happens in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs without the political leadership necessarily being aware of it.

Has it meant a lot for Norwegian engagement on this issue? I mean giving it a central role in Norwegian foreign policy?

Yes. I had a phone call from Susan Eckey at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs when I came back from Switzerland. She asked: ‘Helga, can we meet up for lunch?’ I said yes. And then she said: ‘You know, we’ve got a Labour government now. This is something we want to work on, but the Conservatives weren’t interested.’ So I said: ‘What is it?’ So she told me about this resolution. Then I said to her: ‘You know what? I’ve just had an invitation from PRIO.’ ‘Yes, but that’s splendid.’ Obviously, it came mainly from Torunn [Tryggestad] who is familiar with the UN system. But it also came about because Susan and Steffen Kongstad asked me. I remember that even my old friend Svein Sæther [who was ambassador to Beijing 2008–17] supported it. It was very important. It was Susan Eckey who was the driving force. So it came from two sides. Of course Torunn knew much more than I did about the purely academic side, because I hadn’t worked on this while I was an ambassador.