Dan Smith. Photo: SIPRI

Dan Smith, interviewed by Stein Tønnesson

What I want, if you look at me and my career, is on the one hand, a lot of activism, and on the other, a lot of research. The activism I have engaged in was sometimes in a movement, like the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), but mostly about trying to move things in policy terms. If you look at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), I went to a research institute and I brought it a little bit more into engagement and into policy work. Then I went to International Alert, which was a hands-on engagement organisation and I strengthened up its research and analytical side. So, you know, I’ve kind of always tried to unite the two halves of my personality, research and policymaking, in whichever institution I’m working for.

Stein Tønnesson: And now you are director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Can you unite the two halves there?

Dan Smith: I feel that SIPRI, where I arrived in 2015, is where I have really arrived. For me, this is the job! I mean, I’m not at all criticising either of the other institutions I have led. I’m very proud of both PRIO and International Alert, and I’m proud of what I managed to achieve between 1993 and 2001 at PRIO and from 2003 to 2015 at International Alert. But honestly, it is here at SIPRI that I feel I have the most comfortable seat, the one that is most shaped to the weird contours of my particular intellectual formation, where I can do some of the things that are closest to my heart. Yeah, I’m very happy.

At SIPRI, we have the good fortune to have a constituency that appreciates the importance of good policy research to support policy choices. While it’s up to other people to judge whether the policy choices are good, we do our best to provide the Swedish government and others with firm evidence to support this or that policy choice. We have good relations with a number of different governments and with international organisations, including the European Union and the United Nations, and different agencies within the UN.

And if you now compare the leadership positions you have held in Oslo, London and Stockholm, what distinguishes each of them?

Well, first of all, I’ll tell you what unites them, which is that even during the interview at SIPRI I found out that it had been in crisis and was really in a pretty poor shape. The director and the chairman of the board of governors had stepped down by mutual agreement in order to bring the crisis to an end. But of course, the structural weaknesses were still there. So, in a way, what unites the experiences of running PRIO, International Alert, and SIPRI is that in each case, I was coming into a place that had been through some kind of crisis and was still recovering from it, and was weakened compared to what it could and should be. I think at each place – perhaps less at PRIO, more at International Alert and even more at SIPRI – there was a huge appetite amongst the staff to put things right. Get this behind them and work together to move on to the next level.

The Literary Road to Peace Research

Dan, you were my predecessor as PRIO director. In my first month in 2001, you trained me in the job, and you also continued working for PRIO for some time after that, with responsibility for our huge engagement projects in the Balkans and in Cyprus. As the outgoing director, you showed a remarkable understanding of what a leader needs. Whenever I faced a difficult choice, you spelled out my options and told me what the implications of either choice were likely to be, but you left it up to me to decide.

Let me start this conversation by asking you about your unusual educational background. You studied neither history, international relations, sociology nor any other social science, but English literature. Is not one of your key assets as a leader in peace research your command of the English language? Please tell me what your literary road to peace research looked like. Which schools did you attend, and how did your studies form you as a person?

School education started in a couple of primary schools in England as my family moved from one place to another, and then a year and a half of elementary schooling in Australia, and then back to the second of my previous primary schools in England. I took the national exam of the time; it was called the 11 Plus, and sorted out kids aged 10 and 11 in England into the bright ones and the not so bright ones. It was statistically decided that there would be 20% bright ones who would go to grammar school, and 80% not bright ones who would go to what were called at that time “secondary moderns”. That was an education system that was, fortunately, reformed out by the Labour government of the 1960s, which introduced comprehensive education so that everybody receiving state education (rather than paying fees) would go to the same kind of secondary school.

I was at a very good grammar school. It was – what can I tell you about it? How to shock the Scandinavians? – it was a boys-only school, we all wore school uniforms, we did competitive exams three times a year for the first two years of our time there, and then every half year after that, preparing us for the national level exams, the so-called O-levels – “O” for “ordinary” (which I think is why, in the Harry Potter books, the wizarding exams are called OWLS) followed by A- (for “Advanced”) levels.

I took the O-levels when I was 14, and then sat the A-levels at 16. In both cases, that is a year or two younger than most people do, for two reasons. One was because, when I was in my second primary school, there was a real crowd there; it was the end of the baby boom generation – kids born like me in 1951 – and there were more children than places. So, one day the headmistress walked into Class 1 where I was, and two or three of us were picked out for a quick test. I was 5 at the time. One question, which I remember, was 8 + 7; I had the chalkboard in front of me and I just had to write in the answer. And then spelling about three or four words of about four or five letters in length, so not “cat” or “dog” but, you know, “milk” or something like that. Then, you know, that’s fine, Daniel, off you go into the next class. So, I went up one year when I was 5 years old. I was always the youngest in my class all the way through school.

And then at grammar school, when most schools took five years to take their pupils to O-level, this school took four. So, I was doing the exam two years younger than most of my peers in England. It meant that once we’d done A-level, we had some extra time; that was why the school did O-levels quicker than normal. So, I did my A-levels in two years, but then I took another year to do one of the A-levels again – to deepen my knowledge and get a better grade – and then I took the entrance exam to go to Cambridge.

Dan Smith, aged 3, ‘already researching’. Photo: Private archives

When did you develop your interest in literature and fiction?

I was an avid reader by the time I was 10 or 11, reading everything, mystery novels and so on, and probably some quite strange ones because I just chose more or less at random in the library. Being interested in actually studying literature instead of just consuming it started when I was 15, after I had taken my O-levels. I had teachers at that time in English literature who were themselves inspired by their love of literature, and I think that passed on to me. I became a reader of great novels, rather than just what I happened to find in the library, along with poetry and drama.

When you got to Cambridge, did you focus completely on literature?

Yes. There were people who switched subjects, who were at the university to read one subject and then changed to another one. But not me. I stayed with English not just because I loved reading but because it was the subject I was good at.

And what was your focus during your study at Cambridge? Any particular author or kind of literature?

The first two years at Cambridge – known as Part One – in English Literature, you do almost everything from the Middle Ages to as close to now as you can get. Within those centuries, I particularly liked the drama of the 16th and 17th centuries, Shakespeare and the Elizabethan and Jacobin theatre, and the so-called metaphysical poetry of Donne, Herbert, Marvel and others in the 17th century. After that, for me, there is actually a bit of a blank spot in English literature lasting about 140 years, during which I don’t find very much of interest other than bits and pieces. It is really with the 19th century and the novel that it picks up. My long essay, as part of the Part One exams at the end of two years, was on Jane Austen. She is actually an abiding love of mine. When I have a really serious cold that has knocked me out, once I start recovering from it I read Pride and Prejudice. I always know I’m getting better when I decide to read my favourite bits from Price and Prejudice. In the English lit. course, as the literature became more and more modern I was more into it. For my Part Two, the special period that I took was 1910–1935 – just before the First World War, during it and most of the interwar period. It’s a great period of literature in the English language, with authors ranging from T.S. Eliot to D.H. Lawrence – who hated each other – and everybody in between: from E.M. Forster to Aldous Huxley, Ezra Pound, James Joyce and W.B. Yeats. I did my Part Two dissertation on Yeats. I was proud of that, I thought I did some good work there, and I was told that the examiners liked it as well.

Your background in English literature distinguishes you from most other peace researchers. How has it advantaged you or disadvantaged you in the field of activism and peace research?

I’m not sure. I came out of Cambridge an articulate – probably too full of himself – young man, and persuaded various people into thinking I should be given positions of responsibility.

I could always present myself articulately, I would always perform well, and I wrote reasonably. I don’t think that’s boasting, it’s just being aware that these are skills I have, some of which I have worked at. I think that what Cambridge really gave me in terms of education was that it taught me how to read and write.

There were other aspects of learning how to write, though, and I think it never stops. I benefitted enormously from a style check programme I used in 1990 or thereabouts – that’s after I had stopped being active in the British peace movement. The word processing programme I used was called WriteNow; it came with a free style check called Grammatick, which gave you a detailed, phrase-by-phrase analysis of your writing, emphasising the importance of clarity and simplicity. It was rather brutal, in fact, and told me I didn’t write quite as well as I thought I did. It taught me a lot about the mechanics, the pace and rhythms of written English. I hope I am still learning now how to improve my writing.

I suppose that writing well – even if I did still have lots to learn – may have helped me with the activism; at least, I don’t think it ever held me back in any kind of way.

As far as research is concerned, I don’t think it’s ever been a problem for me that I had a literary education rather than one of the social sciences. There are some people who do find it’s a problem because they know that I don’t have a degree in what they regard as an appropriate topic, neither a master’s degree nor a doctorate. And if they start to get particularly critical about that, I point out that I do have a master’s degree, a Cambridge University Master of Arts in English literature, and I ask if they know what I had to do in order to get that degree. Of course, they start to imagine the most demanding pedagogical programme you could think of. And I point out that what you had to do back in those days was breathe in and out for two and a half years, and then Cambridge University would send you a letter saying we have appointed you to be a Master of Arts. As you can tell, I don’t actually take the paper qualifications very seriously. But I know that many people do.

I think if there is one issue, it is that sometimes in some fields I have felt it would be useful to be more versed in some of the theoretical language and the methodologies that are commonly used in political and social science. On the other hand, you know, I consistently find that people who bring one theoretical and methodological package to the table can’t talk to somebody else who comes with a different theoretical and methodological package.

Perhaps one of the advantages of not having a single disciplinary focus is that it is easier for me than for some others to take a broad view and look at a question from a number of different angles. I have always thought, if something is important and worth trying to understand, I can probably understand at least a part of it. I’ve never been put off a topic because I don’t have the right theory or methodology easily to hand; I just try to figure it out. Maybe that’s where knowing how to read helps most.

The one thing in which my student days studying literature clearly helped was when I started writing about the ethics of humanitarian intervention and the political philosophy of sovereignty. This was an important set of topics for me in the late 1990s and early years of this century. And then I think that both some of the specific reading I had done and, more generally, the literary sensibility, were very useful for unpicking some of the issues involved in, for example, the relationship between the Just War tradition and humanitarian intervention.

Yes, I remember your attitude towards the disciplines from when you came to PRIO in 1993. At that time, I wanted to form a group of international historians at PRIO and you didn’t want it at all. You wanted PRIO to be clearly cross-disciplinary.

Yes.

Dan Smith as a Cambridge University undergraduate in 1971. Photo: Private archives

A Mother’s Tales – and the Library

Let us move back a little. Was there something in your family background that predisposed you towards studying English literature or engaging in peace work? Quite a few of our PRIO Stories tell about wartime experiences having motivated a strong dedication to peace.

Nothing in my family background pushed me towards literature or research. I’m not sure about the peace bit. I am the youngest of three children. My father was born in 1914 – a few months before the outbreak of the First World War – and my mother in 1916, the year that wartime rationing was introduced in Great Britain. They got married in 1940, one year into the Second World War. My father had been working in China and came back for the war. He joined the air force, qualified, and became a flying instructor, then deployed to Canada to instruct Canadian pilots joining the Royal Air Force. My mother also crossed the Atlantic to join him. For most of the time, he was stationed in North Battleford in Saskatchewan, one of the prairie states, and that’s where my mum lived too.

Towards the end of the war my father was deployed to Northern Ireland and flying ocean patrols. My mother came back with her one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, on a transatlantic convoy; this was the eastward journey, the more dangerous trip to take because the supply ships and troop ships were full and were targets for German submarines. They were back in Britain before the end of the Second World War, and my brother was born shortly after it ended. They went out to China after the war was over – sometime in 1946, I forget when – when my brother was still a baby, and my sister by that time was a two-and-a-half or three-year-old. It must have been a hell of a journey on a ship going out to China. They left just before the Chinese revolution was completed in 1949. They were then sent to a couple of other places, including Sri Lanka, which is where I was born in 1951.

I was about 18 or 19 months old when we left from there and then went to Kenya, living in Nairobi. That’s where I had my second birthday. We were back in England after about a year, and I think my father was not particularly successful at that time; he went from one job to another for a bit. And then he got a position that started in 1958 – while I was at primary school in England – that involved moving to Australia. Which, as a family, we did at the end of – what was up until then – the hottest summer in the UK, 1959. I am probably one of the last generation of people who took an ocean voyage for the purpose of getting from one place to another, rather than for a cruise or a laugh, or something like that, or as a crew member. We went out on the SS Stratheden of the Peninsula & Orient shipping company, leaving from Tilbury docks in very late August of 1959. I had my eighth birthday on the ship as we went out. It took about four weeks to get to Melbourne, which was where we lived till we came back to England.

Do you remember anything in particular that your parents said to you about war and conflict, in your childhood?

My parents separated around the time we came back from Australia, and because I was the youngest child, my mother and I spent lots of time together. At Sunday lunches, I would prompt her for tales, for stories. She was a rather reluctant but very good storyteller, and talked vividly about life in Canada, about the convoys, about China and so on. So I have very strong images of all of that, and about the things which worried her, and the things that didn’t worry her. For example, there wasn’t much point in worrying about things like German submarines; of course, you did worry about them, but there was no point in letting the worry affect you too much. It was more important to know that you had a proper supply of nappies and other products for the baby who you were bringing back.

When my mother moved to China, one of her worries was about food, because she knew that she would have to go to some formal banquets and meals. She was just about 30 when moving out there, and obviously she had quite a lot of experience because of the war and going out to Canada, but in other ways she was a quiet suburban young woman from West London. And suddenly she was in exotic China where she would have to eat with chopsticks at smart meals. So indeed, very soon after she landed in China my father was invited to a dinner to welcome him, and she should go as well of course. She sat up until about 2 or 3 o’clock the night before the dinner, practicing eating toffees with chopsticks. My mum’s stories were a big part of how I learned about my family background.

If we now go to your own recollections from your childhood, what were the events that influenced your feelings about peace and conflict? When is the oldest memory that you have of something that had to do with conflict?

I’m not so sure really. I’ve been thinking about this since I agreed to do this interview. I remember the Cuban Missile Crisis, and I remember some news about the Partial Test Ban Treaty, and the feeling that it was a good thing, because maybe our milk was being poisoned from radioactivity and so on. Nothing very specific… I am not one of those people who remembers where I was when President Kennedy was assassinated. Five years later, I remember where I was when I heard the news that Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated. And I think by then, which is 1968, and I was sixteen, coming on seventeen, I knew about the Vietnam War and war in the Middle East. I was opposed to the American role in the Vietnam War. But I didn’t have particularly strong views about any of those kinds of issues until after I went to university in 1970.

Which other things in life really fascinated you when you were a teenager?

I hesitate to say about some of them – I think I was a pretty ordinary teenager. One thing I can think of, that I did a lot, which would seem to be retrospectively pretty significant given my career, was that I read military history. As I already told you, I was an avid reader, and the public library was a fantastic resource. My technique was to pick a book that looked interesting and if it was, if I got lucky, so to speak, I would read my way through that author until one day there wouldn’t be one on the shelf that I hadn’t read. Then I would just move on to another author. At some point, on one of the occasions when I felt like reading some non-fiction, I read J.F.C. Fuller’s Decisive Battles of the Western World.[1] It is one of the classic works of military history, though I didn’t know that till later. I was about thirteen at the time, I think. I also read Liddell Hart, who was the other major intellectual figure of the inter-war years, trying to make sense out of all things military after the carnage of the First World War. I was fascinated by those kinds of things. But it wasn’t particularly the Second World War and modern war that fascinated me; I spent much more time reading about and wanting to know the details around medieval and Roman battles.

We have something in common there, I did the same.

I think it’s perfectly possible that at any point in my life I might have taken a different turn, and then reading military history when I was a teenager would have been just one of those things that a strange young boy did. I think very often we read people teleologically, so that we understand them now for who they are, and then we look into the past to see those things which fed towards the person who we now know. Given different circumstances, at certain key points, if I hadn’t gotten this job or that grant, I could have moved in a completely different direction.

For example, if I hadn’t got the job at PRIO, maybe I would have focused more on writing crime novels – I’d had three published by the time I started in Oslo, as well as two short stories, and I was working on a fourth that has never seen the light of day. Perhaps I would have made a success out of that. Then probably one wouldn’t think that reading military history as a teenager was particularly significant.

I think very often we read people teleologically, so that we understand them now for who they are, and then we look into the past to see those things which fed towards the person who we now know. Given different circumstances, at certain key points, if I hadn’t gotten this job or that grant, I could have moved in a completely different direction.

We try to make sense of a lot of coincidences…

Yes, exactly. A friend of mine who was helping me as a PA [personal assistant] when I was head of International Alert once looked at my CV and said to me, “Wow – you just took a straight line through life towards this job.” But that is not at all how it felt at the time. I just meandered along doing what I was interested in.

Do you remember any dreams about or ambitions for your future?

No, I was never able to answer questions about what I wanted to be when I grew up. When I was 17 or 18 and on the verge of going to university, I still had no idea what I wanted to do. I just wanted to go to university, have a good time, see what came up, and carry on.

Becoming a Leader at 22

One day in 1972, I joined the sit-in over a rebellion against the exam system. The system was strange, consisting of a series of three-hour exams into which, under pressure and feeling nervous about your future, you tried to encapsulate several years of learning. It’s probably a good system for finding out who can do well in three-hour exams but it’s hard to see it as a serious way of assessing how much you have learned and understood. Students started to rebel about this and wanted other systems of evaluation. I don’t think anybody thought we should do away with exams completely but wanted more emphasis on dissertations and on continuous assessment through the semesters of being at the university. Several, I suppose very politically motivated, students decided this would be a good issue on which to have an occupation of a major university building and I decided it would be a good idea to join in. If you want a day that really changed my life, that would be one of them. It started me on a course where I was associating with the political types all the time. Whatever we agreed or disagreed about, we wanted to change society, we wanted to change the world. We were of course young and enthusiastic and foolish in many ways, but I think that most of the things I was against at the time, I’m still against now. I’m just not as sure as I was when I was 21 about how to change them.

A couple of months later, I was elected to the student union’s Executive Committee. Then I was launched into student politics for a year and a bit. When I left university, I had decided that I wanted a job in which I would do some good.

I guess I was still young and foolish and idealistic about this so I was not perhaps as open as I should have been to the idea that there are many different ways to do good. What I meant essentially was that I wanted a movement job. So, I went to work for an organisation that, up until the time that I saw the advert for the job, I thought had probably folded: this was the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). CND had been very big from 1958 to about 1963 or ‘64, before the Partial Test Ban Treaty had taken some of the air out of its sails and it went into a quiet decline. The anti-Vietnam War movement and to some degree the anti-apartheid movement became more fashionable radical forces. Well, I saw a tiny little advert for a national organiser. I could tell from the salary that they were offering – which was a pittance – that they were not going to get anybody who was experienced and really knew what to do, so for the hell of it I applied and got the job. I started there in June of 1973, straight after I graduated. It was a very small office staff, just four of us, in a two-room office on Gray’s Inn Road in central London, very ramshackle, very dusty. There were a National Council and Executive Committee who ran this organisation, which still had about four or five thousand members.

That autumn, the General Secretary, the head of the office staff, decided to retire. To my surprise, he and the chairman of the campaign sat down with me and said, well, they thought that I should have the job. So, I had just passed my 22nd birthday when I became the General Secretary of a small national organisation.

We wanted to change society, we wanted to change the world. We were of course young and enthusiastic and foolish in many ways, but I think that most of the things I was against at the time, I’m still against now. I’m just not as sure as I was when I was 21 about how to change them.

Did that predispose you to become a leader?

Yes, it did.

At Brighton seafront in 1985. Photo: Private archives

Discovering Peace Research

Was it the job offer from the CND that led you into your interest in British defence policy?

Yes, exactly. That’s the route in. Because then what happened was that I took the executive decision, in which the chairman backed me, to improve our campaign literature. Our literature tended to appeal to people who agreed with us already. That’s not completely useless because they might not know they agreed with us so simply stating a position could be useful for recruitment. But it wouldn’t actually win over somebody who was open-minded and had questions. Anyway, over 1974 and 1975 we wrote and published a number of pamphlets, fact sheets and briefings with an emphasis on facts and arguments.

Another important shift in focus was that I said we’re not a mass movement and we’re not going to be one very quickly. I was wrong about that because by the beginning of 1980 we were a mass movement again, and that was only five or so years later. But as far as I could see at the time, there was nothing that would make us a mass movement.

So, I thought we needed to build our parliamentary strength. We needed more Members of Parliament to better understand the issues and our new literature would help with that. We did work with other constituencies as well, such as universities and trade unions, but I thought the parliamentary aspect was particularly important. I used to write a monthly briefing for Members of Parliament.

During those years, I started to meet people who were involved in research on these issues. I met Andrew Mack, who in later years directed the Peace Studies Centre at Australian National University, then became an adviser and speechwriter for [UN General Secretary] Kofi Annan, and after that the progenitor of the Human Security Report. I met David Holloway, who was one of the top experts on Soviet policy and strategy; he was at Edinburgh University at the time. Sometime after, he moved to Stanford [University] in California, where he still is. And I met Mary Kaldor, who was at that time at a research unit in Sussex University.

Meeting them and others was important and even inspiring. I started to realise that this was a world that I could get into. If I remember right, I invited myself to lunch with Andy Mack one day in early 1975, and asked him if he thought I could be the kind of person who could get a grant to do some peace research, and if so, how would I go about that? And he answered yes, and helped with useful introductions to other people. By then, I knew Mary Kaldor and we were working on a pamphlet together with David Holloway and Robin Cook, who 20 years later became the UK foreign secretary. Mary helped me a lot with my first research proposal, which I submitted in the summer of 1975. I was lucky with it and started doing full-time research in January 1976, leaving my job at CND after two years as General Secretary. And you know, just as I said about the reason why I did English, the reason I started doing research was that I felt it was something I was good at and enjoyed. It was the part of the job at CND that I had really liked.

After that, one grant led to another and then to a precarious mixture of research grants and publishing income from different things. By the end of the ‘80s I felt that my life was a little bit financially and economically insecure, and I was beginning to come towards 40, which is a milestone. And I asked myself: in 10 years’ time, when I’m coming towards 50, do I want to be in the same position as I am now? And my answer was a clear no, I didn’t. I still loved research and writing but other aspects were not so good. So, I set about doing what I could to improve things. Perhaps this seems very odd and off topic, but one of the things that I did was give up smoking. I think it was a symbolic expression to myself about the importance of my own agency. If I want to do it, I can.

So, I was doing a fair amount of reflecting on myself at the end of the 1980s, start of the ‘90s. And I remember thinking and discussing with people what the ideal job for me would be. There was my interest in research, and my wish to connect that to changing the world, and a little experience of management. That came about because, although I had left CND as an employee, I stayed active in the peace movement. I was chair of European Nuclear Disarmament in 1981–82 and vice chair of CND from 1984 to 87. And I put in a considerable amount of time unpaid, which was part of why my life was financially and economically insecure. One of the things I did was look after the internal organisation of CND. By then it was employing about 40 or 50 staff and therefore had responsibilities as an employer. The staff needed job descriptions, proper terms and conditions, an evaluation process on their performance, grievance and disciplinary procedures. It’s a bit of a paradox that unpaid part-time elected officers like me were managing full-time paid staff but that didn’t change the fact that we had employer’s responsibilities. We did what we could.

With that experience I had some sort of basis for saying, towards the end of the ‘80s, as I looked for ways to change my life, that the ideal job for me would be to run a small peace research institute. So, I was already thinking about that for a couple of years before I applied for the PRIO proposition.

Coming to PRIO

What did you know about PRIO at that stage? And how did you get in touch with PRIO? What led to your application for the directorship?

What did I know about PRIO? I knew the Journal of Peace Research and I knew the Bulletin of Peace Proposals (now Security Dialogue) and, you know, read them both from time to time. I had met Johan Galtung a couple of times. I’d met one or two other people.

In 1982, I think, I visited Norway at the invitation of a peace group in Porsgrunn who were having a peace festival. At first I declined because my partner and child would just be coming back from America, and I wanted to be with them. So, they said, well, bring them both, and we had a lovely time in Norway, a week or so, and when we were in Oslo, we met and stayed with Mari [Holmboe] Ruge, who was one of the founders of PRIO back in the ‘50s.

Then, quite how it happened, I’m not sure, but Nils Petter Gleditsch wrote to me at some point in ‘91 and asked me to help out with a piece of work that he was engaged in. It was about the economic consequences of reducing military spending, which was one of the many topics I’d touched on in the late 1970s and early 1980s. After it was done, I remember getting a note from Nils Petter enclosing the advert for the PRIO directorship, and he said, you know, something like “post project employment opportunity?” So, it’s all his fault.

Had you not met Nils Petter before he wrote to you?

Maybe I had, I’m not sure, ask him!

He would remember, that’s true, but I also recall that he was the one who contacted you and brought your name into the process. I was at PRIO at the time. When you arrived at PRIO, how were you received?

Well, I think pretty nicely. It was rather odd because I had only just been appointed to a two-year contract as director of the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam. But I had already applied for the job at PRIO, which was a bigger opportunity and what I really wanted. But I felt I couldn’t just leave the people in Amsterdam. So, we finally agreed that there would be a long period of notice for the Amsterdam institute. I think I was offered the PRIO post in August of ‘92 and I started in the beginning of April 1993. During those eight months I came to Oslo for about a week each month. Hilde Henriksen Waage was the acting director and Grete Thingelstad was the administrative director. I met the people there and got to know them and their work before I had to take any decision about things.

What I hadn’t appreciated until I got there was just how weak the situation of PRIO was at that time. I think it’s not an exaggeration to say that two thirds of the income was provided in the single core grant from the Ministry of Education, Research and Church [Kirke og undervisningsdepartementet]. And to be that dependent on a single donor is in any case a weak position. In addition, there were supposed to be five permanent contracts, but only two of them at that point were occupied by people who were there. Two of the other three were on leave and the third was in the process of leaving.

There were two short hires to replace the ones on leave. One was Pavel Baev, who is still there. I have always felt good about the work we put into keeping him in Oslo, and about the work he was doing that has fully justified it. In addition, there were some PhD candidates, one researcher who was supported by an external grant, six or seven students and that was it.

So PRIO was small, dependent on one donor – and there had been some internal disputes as well. Even so, the spirit inside the institute was quite good. But one of the first things that happened was the proposition that what were called the foreign affairs institutes of Oslo – the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI) and PRIO – should be unified in the name of efficiency. We had to sit on a committee chaired by the Nobel Institute director [Geir Lundestad] on what could be done to unite the three institutes. It was a very strange experience and strange introduction to my ideal job that somebody seemed to want to take the institute away from me.

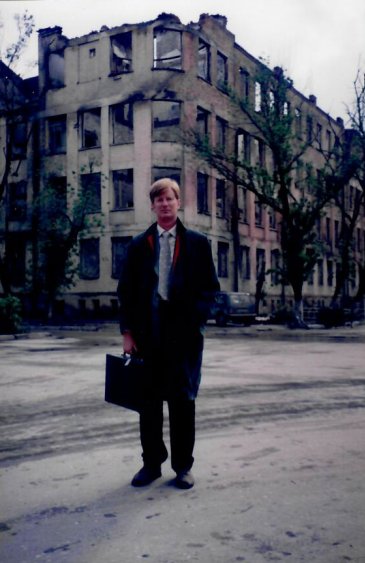

Grozny, Chechnya in October 1995. Photo: Private archives

Yes. This has been a repetitive occurrence over the years.

I think it’s fundamentally misguided. It’s important to have different centres of knowledge and understanding, which even from a pure market point of view can compete with each other for grants. The overhead, the transaction costs of keeping these places going as independent units is astonishingly small, if you look at what the normal transaction costs are in most departments of government.

Anyway, we managed to avoid this misguided unification and needed to build up the institute, strengthen it. I opted against renewing the long leaves that two of the senior researchers were on and that gave us a little bit more room for manoeuvre. We had some good fortune here and there with grants from the Foreign Ministry, the Research Council and the Ford Foundation.

As you know, the position of director at PRIO is offered on a four-year contract that is renewable once – two four-year terms. Towards the end of my first term, I felt we were making progress on the main issues.

But a big challenge now arose because it became clear that there was going to be a major reduction in the core grant. We addressed this challenge in three ways. First, one day, Helga Løtuft, the administrative director, and I decided to work out the application for the following year’s core grant in a different way. Instead of starting from what we were already doing and seeing how to allocate resources for it, we decided to start by working out what we wanted the institute to do, given its strengths and capacities and also areas where things needed to be improved. We worked out how many positions of different kinds we needed and, based on experience, how much each position cost. And we put it together and it came out as quite an aggressively ambitious budget with a big expansion written into it, despite knowing that the core grant would be smaller. And the board adopted that and backed us. When, nearly two years later, we got to look at how we’d done in that year for which we had done the aggressive budgeting, it had more or less worked out.

The second thing we did, at the same time, may have been unprecedented for researchers in Norway. We decided junior researchers can also have permanent contracts.

From my perspective, this was an easier and less dramatic decision than it may have seemed at the time. The truth is that tenure is not forever. If the institute went down or it went bankrupt or we were losing money, then people would be made redundant anyway.

So, a permanent contract does not guarantee a job for life. This is one of the big myths I have discovered in Scandinavian research. Everybody wants the permanent contract but doesn’t realise it’s not permanent. You have to come from the UK or America in order to really understand how impermanent permanence is. So broadening eligibility for tenure was, for me, relatively straightforward. Yet it was also important because it told junior researchers that the institute was committed to them. In that sense, it gave them more security and that helped generate a feeling of being together.

The third part of the response was that everybody had to raise salaries. Up until that point, it was assumed that senior researchers’ salaries were covered under the core grant. With the core grant shrinking, that could no longer be the case. Now, everybody had to raise a large percentage of their salary. I hope that at the time, everybody understood that we would do everything to avoid having to let people go if research applications weren’t successful. But everybody had to understand that we were all in the same boat, all rowing in the same direction, and therefore all researchers had to put their best effort into raising part or all of their salaries.

And, you know, my salary was also put into various projects. It wasn’t completely funded from the core. So, we were all in that position. I guess some might ask why people who are doing such important work should have to work so hard to raise their own salaries. I get that. But the reality was that, while the collective that is the institute was fortunate to have a core grant of n million Norwegian kroner from the Research Council, what we want to spend is 4 n. So, we just have to raise the 3 times n from somewhere else. Let’s get to it.

Funding and Policymaking

If I remember correctly, when PRIO hired you from abroad, our expectation was that you would generate international funding, and we thought your lack of a Norwegian network would be a weakness, so we would need to have someone help you build good relations with the actors on the Norwegian funding scene. Then, yes, we got a little money from the Ford Foundation, but the big success of yours was with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Norway. You managed as a foreigner to handle the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in a way that I think a Norwegian director might not have managed. Was this also your impression?

I think that’s possible. Some international funds came in, as you say, but one of the problems back then was everybody knew how rich Norway was. So, they asked why Norwegians didn’t just get Norwegian funding. It was not a completely shut door, but I always felt I was working uphill with those kinds of things. And some of the EU possibilities that now exist were not so readily accessible then.

What is the purpose of studies of signs of imminent conflict, for example? From one point of view, it is to test models for explaining and understanding conflict. But from another point of view, it is to assess the risks and see if something can be done to prevent the violence being as terrible as it otherwise could be.

In the Norwegian Foreign Ministry, I did have good working relations with different officials, and also with Jan Egeland, who was the state secretary at the time I started [1990–97], and several of his successors too. I think that they realised that I was not only interested in research for its own sake, but also to provide an evidence base for policy. We didn’t have all of the current vocabulary back then; we didn’t so easily refer to “evidence-based policy formulation”, but that was what we were talking about. I mean, what is the purpose of studies of signs of imminent conflict, for example? From one point of view, it is to test models for explaining and understanding conflict. But from another point of view, it is to assess the risks and see if something can be done to prevent the violence being as terrible as it otherwise could be. And in the 1990s, that was a huge new area of concern opening up because, with the end of the Cold War and, separately, the increased immediacy of global news coverage, civil wars and genocide risks became more visible and a matter of urgent political concern for some European governments.

Yes. It is clearly part of your profile to combine research with policymaking, providing information and suggestions for new policies, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs liked that very much. Did you feel that the PRIO researchers shared that ambition at the time?

Some did. Some didn’t. But generally speaking, even those who are not so inclined can be quite flattered if and when their foreign ministry or other policy actors pay attention to what they have to say. I think that the disdain for having policy influence is sometimes self-protective.

Doing this has grown much since your time, and now we have to report on the impact of our research all the time, both in applications and reports.

I think it can sometimes be overdone. It’s a problem when impact assessment becomes a box-ticking exercise. There’s also the complicating issue that very often policy actors do not want to acknowledge that they got the idea from an independent researcher.

But it is very much worth looking at impact – at whether your research conclusions have an effect – because it encourages you into a different way of thinking about your work and how to communicate it. The truth that a lot of researchers find hard to swallow is that a big, scholarly research report can be helpful as a background, but the decisive impact is probably best and most often achieved through a conversation and a two-page note that simplifies everything right down to bare basics. If you write more than that, most people whom you want to reach and influence simply haven’t got the time.

So, put it in two pages, in simple, clear English, stress the recommendations and just make sure that you show in some way that the recommendations are evidence based. And then they will ask somebody more junior to look into that report and take a look at it.

Kosovo dialogue seminar in Herceg Novi, Montenegro, 1997. Photo: Private archives

PRIO’s Three Heroes

When we had our 50th anniversary, [the former Dagbladet journalist] Gudleiv Forr wrote a book about PRIO’s history. That book has three main heroes: Johan Galtung, Nils Petter Gleditsch and Hilde Henriksen Waage. I wonder if you could say a little about your cooperation and relationship with each of them.

Well, I met Johan a few times in the ‘80s and in the anti-nuclear context. And again, when I’d taken over as director. He came and gave a couple of lectures. I wanted to maintain that connection with Johan.

He was very critical of my views about the NATO campaign against Serbia in 1999. And I thought that he was really, like some others, too soft towards Serbia and Serbian nationalism. And there was a kind of falling out at that point. I felt that he started to use needless rhetoric about PRIO, claiming that we had just become a security studies institute. I heard him express this criticism in a talk he gave at a conference in Tromsø around 2000. The sad thing was that, at the time, PRIO was engaged in supporting dialogue work in the Balkans, bringing people together from different communities, with similar work going on in Cyprus and between Greece and Turkey and contributing to the Greek Turkish détente which started in 1999. And at the same time, we were producing research that was being taken very seriously. And he could have seen that combination of research and active engagement as something that was at least close to what he had dreamed of decades before. But I don’t think this disagreement had any particular effect in or on PRIO. It was one of those cases where there had been a parting of the ways between an institution and one of its founders – an evolution in different directions – and that’s okay.

Nils Petter, well, as I said, he was the one who first linked me to PRIO, so I am forever grateful for that. He was a tremendous editor of the Journal of Peace Research (JPR). He did a huge amount just through his personal effort, through his personal energy to systematise things and to raise standards and to make it one of the premier scholarly journals in the field. I think a lot of his research also has been interesting, but I think he has for years and years got it completely wrong about the relationship between climate change and insecurity. To my mind, he has systematically set out asking the wrong questions and is therefore getting answers that are not very helpful. And using a methodology that is completely inappropriate, because it’s based on studying the past and deriving trends. Yet one of the fundamental points about today’s environmental crises and especially climate change is that the future will be different from the past. That means that research based on studying one hundred and sixty countries over the last 50 years is bound to be flawed. But, you know, I like him as an individual and I think he’s made a huge contribution to peace research with JPR, and with his own work as well.

Concerning democracy and capitalism – these are his other big contributions in later years, first researching the democratic peace and then moving from that to a theory of a capitalist peace – do you think it makes more sense to base those theories on historical statistics?

I’m not sure about the capitalist peace, to be honest, not because I have theoretical divergences on it but because I haven’t read enough of that. But on the democratic peace and the bell-shaped curve identifying where the greatest dangers are, I think that is very interesting work.

Nils Petter has said jokingly that in the ‘60s we said: Make love, not war. But now it seems to be more relevant to say: Make money, not war.

Really? The interesting thing would be to listen to Nils Petter reconcile that with his longstanding view that the development of the European Economic Community and European Union did not contribute to peace in Europe. You know, he was a devout opponent of Norway joining the EU in 1994. On the broader theme of economic cooperation and trading relations, I think they very often do contribute to peaceful relations, but I think there are a lot of nuances. It’s interesting how trade can survive even in wartime, as it did between Britain and Germany during the First World War, and between England and France during the Napoleonic Wars. According to legend, Napoleon’s army marched to Moscow in British boots. Closer to our time, during the wars in the western Balkans in the 1990s, there was plenty of illicit trading across the conflict lines. There are also times when you can see trade relations leading to anything but peace: look at how they are poisoning the international atmosphere at the moment. So, trade relations, if not properly regulated, may lead to all kinds of difficult issues.

I agree.

On the other hand, you can turn this around and say that trade is a form of cooperation, which at its best is a win-win. There’s a whole set of theories on this. I have been quite struck by a book by Paul Seabright called The Company of Strangers.[2] It’s all about how we are bound together by co-operative relations with people whom we have never met. And if you think about nationalism, one of the things about Benedict Anderson’s idea of an imagined community[3] is that you have to imagine unity and closeness with people whom you’ve never met but with whom you think you are united by, for example, ties of language or religion or custom or whatever. Today, there’s another kind of connection with the people who make the shirt you are wearing. With the people who will be manufacturing the vaccine that we need in order eventually to have immunity against the COVID-19 disease.

Binding of the world together through cooperation should be a good thing for peace. And you could say it’s making money and call it capitalism. But you could also see trade as a form of cooperation and make that the basis of your theory.

Yes. Transnational cooperation and integration make up one of the three corners of Bruce Russett’s peace triangle.[4]

You asked about Hilde as well. She was the acting director in the period between Sverre Lodgaard and me. She was deputy director for a while. After she completed her PhD, she got involved in a very big argument with various Norwegian political figures over her work on evaluating and assessing the Norwegian back channel that led to the Oslo peace accords in 1993. She told me once that she blamed me for that because, one day soon after she had finished her PhD, I strolled into her office and remarked that I had a brilliant idea for what she should do next. And that was to do a proper assessment of the Norwegian back channel, not a quick three- or six-month evaluation, but a real assessment of it based on the kind of research that a historian would do.

Binding of the world together through cooperation should be a good thing for peace. And you could say it’s making money and call it capitalism. But you could also see trade as a form of cooperation and make that the basis of your theory.

She went for that and produced two reports. And it was the first one in particular that caused the trouble, which I think in some ways was a fake controversy. She never said that Terje Rød-Larsen did not deserve credit for what he had done. She just said that other people also deserved credit for the Oslo back channel: it had been set up or prepared for him and then he came in and he did well. And it was really strange that there was so much vituperation in the air over that. But she stayed remarkably calm. I think she conducted herself very well during that time.

More generally, she was very popular and helpful with a lot of the researchers, especially the younger researchers. She played a very important part in creating the good atmosphere in the late 1990s, as we built up towards really being a serious research institute.

Yes. That’s something I benefitted from when I came as your successor.

Engaging in the Balkans and in Cyprus

We should go into the two big projects that you built up at PRIO, in the Balkans and in Cyprus. Could you say a little about their importance and degree of success?

The thing I regret about both of them is that they were never really integrated enough into the mainstream of PRIO’s work. The Balkans work had started way back. Magne Barth, who was at that time deputy director of PRIO and editor of Security Dialogue, and later joined The Red Cross, connected me to this project at the Nansen School in Lillehammer. The principal was Inge Eidsvåg [Rector of the Nansen Academy, 1986–98]. He had developed a project aiming to bring people from the Balkans to Lillehammer for what was loosely defined as education, training and knowledge transfer about democracy and conflict resolution. I was asked to give some lectures there and, as it happened, I think I was the external lecturer who came most often to Lillehammer during the first semester in autumn 1995. Over time, the Nansen Academy changed the emphasis to dialogue. It was where people from diverse parts of the former Yugoslavia could get together and discuss issues that they cared about from completely different perspectives. And then it produced a big spin-off.

In the summer of 1997, two women who had been on that course, both from Priština, the capital of Kosovo, one Serbian, one Albanian, asked if I would agree to give a talk on the themes that I had spoken to them about – but do it in Priština. And I said yes. I didn’t tell them until a couple of years later that the only reason I accepted so quickly was because I thought they would never be able to arrange it, so I was just being nice to them. But they got to work and eventually came up with a three-day dialogue seminar to be held, not in Priština but in Herceg Novi in Montenegro. There were going to be three of us giving talks: Steinar Bryn from the Nansen School, myself, and a third one, who dropped out because he said the way he was treated was very unprofessional, not being given a firm date, no assurances that his expenses would be covered, and no certainty till the last moment about whether or not it would happen. As a result, it turned out to be just Steinar Bryn and me.

It was quite a dramatic trip there because there was fog and the plane from Belgrade was delayed and then diverted and didn’t land at the local airport. So, Steinar called another former student of the Lillehammer course to arrange for someone to drive me through the mountains to Herceg Novi in the middle of the night. I remember that Steinar was rather anxious that, after all, I might not arrive. But I did and there we were, with a plan for a three-day seminar with three lecturers, but only two of us present. So, the plan went out the window; we just made up the programme as we went along. It was a whole lot of fun.

And of course, it was tremendously successful. The fact that we were improvising and had to be flexible meant the sessions were responsive to the participants. And it was very exciting. I mean, Serbs and Albanians were meeting for the first time, knowing what they thought and believing they knew what the other one thought and not needing to learn anything. And then just finding out about each other in the most extraordinary way.

Out of that, we built the idea of a continuing dialogue project, which came to be quite big with, first of all, four centres and then eight, and I think a couple more were added later in places all over the former Yugoslavia. People from the different ethno-national groups worked together to support dialogue in the localities.

From left: Goran Lojancic, Dan Smith, and Inger Skjelsbæk in Herceg Novi, circa 1998. Photo: Private archives

There were one or two people at PRIO who did work on the Balkans and were connected to the project. I suppose the one who came most often was Inger Skjelsbæk, who later became a senior figure in PRIO and now is a professor of psychology at the University of Oslo. She came and participated in dialogues and got to know people, got to understand things about the Balkans. And there was also Victoria Einagel, who was doing PhD work at the University.[5] But as I say, it’s a regret that, even when we hired a coordinator at PRIO to run this very big operation, it never came enough into PRIO. I think that one of the difficulties is that it’s sometimes complicated and slow for academic researchers to absorb something new into their research portfolio. This is much easier in the policy research context where I function now in SIPRI.

Serbs and Albanians were meeting for the first time, knowing what they thought and believing they knew what the other one thought and not needing to learn anything. And then just finding out about each other in the most extraordinary way.

One difference between PRIO and SIPRI is that despite what we have said about the connection to policy making, PRIO remains a much more academic institution. That’s in its institutional DNA and in what’s prized there. By contrast, at SIPRI, we have only one person whose main function is to do her PhD. For anybody else who is doing a PhD, it’s in their spare time, a product of research they’ve already been doing. It’s a very different approach.

As far as Cyprus is concerned, I think you probably know more than I do about the establishment of the PRIO Centre in Nicosia because while I was at PRIO we just had an office in the Ledra Palace [in the UN-administered “Green Zone” between North and South Cyprus]. It was a connecting point for us to go through – we could cross regularly from North to South and so we could bring participants from both the Greek Cypriot community and the Turkish Cypriot community to meet in the Green Zone. But I think that, as I left, the activities and the portfolio of the new PRIO Cyprus Centre became much bigger. And Greg Reichberg was there for a while (2009–12) as centre director. There was some real research being done there, which there wasn’t while I was director and running that programme.

Yes, when I came to PRIO in 2001, you and I first had one month together where you continued as director and I got a chance to talk with all the staff. And then afterwards you served for a while as the leader of the Balkans and Cyprus projects. We made an attempt to get more research into the Balkans project, but it did not succeed very well, and the Balkans project became dissociated from PRIO. With the Cyprus project, I chose to go the opposite way and really emphasise it, lobbying and working actively with the Foreign Ministry to upgrade it, so it could become a real centre and hire local researchers who would do both research and engagement activities. I’m quite proud of what has since come out of the PRIO Cyprus Centre. In our PRIO Stories series, Cindy Horst has made an excellent interview with Mete Hatay about this whole story.

Yes, it was really pleasing to see what was built from that start in Cyprus, that was great.

The PRIO Centre for the Study of Civil War

Let’s talk about PRIO’s application for one of Norway’s first Centres of Excellence. It involved big funding with more than ten million kroner annually for ten years. Could you explain how you brought PRIO into that process?

When the information about the new funding facility for Centres of Excellence came through, I thought that we really had to discuss going in for it. This was obviously very ambitious for us but, even if we were unsuccessful, which seemed likely, I felt it gave the institute a chance to talk together about what we wanted to be doing. If I remember rightly, the initial concept note needed to go in before I stepped down as director and, about the time I stopped, we learned that we were invited to go in for the second phase of the process. That was when the details started to be worked out with all of the Centre’s different working groups. My memory of this is a bit vague but I think it’s just after I stopped that those detailed discussions started.

Yes. There was a two-phase process where PRIO first needed to send in a short application and then be invited to join the second round where we would make a thorough and elaborate application. The process was well underway when I arrived, so I don’t remember any discussions about whether or not to apply.

I remember feeling that I was leaving PRIO with the opportunity to take this further step. What I didn’t realise was that it could actually succeed. Well, I mean there was no other international studies centre that got the Centre for Excellence award, isn’t that right? And PRIO’s was the only social science centre.

Yes, there was one humanities centre (medieval history), but ours was the only social science centre and it was one of just two that were not in the university sector. There were ten altogether.

It was quite a thing.

Yes.

Quite a thing to have dared to go in for it, and even more of a thing to have achieved it.

It was a great achievement. Also, the PRIO Centre for the Study of Civil War (CSCW) did something that not all centres managed. That was to use the big funding as a platform for applying for additional funding. So, by the end of the Centre’s 10-year period, it had more funding from other sources than it had from the core funding.

That was very smart. The other thing I remember us discussing was the intellectual substance of the Centre. What big questions would it be asking? And at a more practical level, how would PRIO be able to contribute to answering them?

It was important that there would be a degree of integration between the Centre of Excellence and the institute so that it would strengthen the latter in the long term. But it was also clear that the new funding facility in the Research Council of Norway was not meant simply to finance what an institution was doing or planning to do anyway.

Yes, so after you left PRIO and were watching it from a distance, what was your impression of the way your work has been followed up?

It seems to me that PRIO has not gone into more engagement than it did while I was there. In northern Europe, there seems to be a particular intellectual formation that makes it more difficult than it is in the UK or the US and some other places to understand the idea of combining engagement with well-grounded research. It surprises me that in some ways the lasting and most influential legacy I left behind from my years as PRIO director was the strengthening, out of all recognition, of academic research. If you had asked for my forecast at the beginning, I would have said that strengthening research is important, but connecting it to policy and engagement would be the thing I most wanted and expected, because that’s more me. But yeah, I think the PRIO I joined had nine researchers, most of whom were PhD candidates, and the PRIO I left had thirty-plus and was just about to get the Centre of Excellence. I don’t know how many PRIO has now …

The total number of contracted staff in 2019 was 136, when all part-time contracts are included, but that figure includes both researchers and administrative staff.

Impressive, and that growth was kicked off during the nineties. I don’t know what would have happened if the idea of merging PRIO, NUPI and the Fridtjof Nansen Institute back in 1993 had been implemented. Had that been attempted, I think it would have failed with at least one casualty along the road. Independence, however, has been a visible success.

We have been saved several times from such a merger. One very helpful thing was the statutes of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, which obliged them to stay in Fridtjof Nansen’s home at Polhøgda.

Yeah, we also discovered a quite helpful clause in the PRIO statutes. If the institute were ever closed down, everything it owns would go back to the Institute for Social Research.

A new attempt was made more recently, when the building of the United States embassy in central Oslo became vacant. There was a plan to co-locate all the foreign policy institutes in the building.

Why do they have these projects? Why does it matter to them? Who is it who came up with that idea?

This happens through personal contact between politicians, policymakers and some institute leaders.

Huh.

But let us return to your career as a leader. I remember how you were lying on a beach, reading The Economist, and you found an advert…

International Alert

No, it wasn’t a beach, it was a balcony. I was in Athens for six months as a guest fellow at the Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy research. I had gone there partly with the idea that I might be able to set up a centre for dialogue, research and policy in Athens. I had very good contacts there, as well as in Turkey, Cyprus and the Balkans. The region had had lots of needs and possibilities, neighbouring the Middle East as well. It seemed like a very good place to have a research and dialogue centre focused on conflict, peace and politics.

I had some grand ideas, but it was clear to me after a couple of months that this was not going to fly. So, one day I was lying on my balcony soaking up some spring sun, and thinking about the future, and one part of my brain said, “OK, you’ve tried Athens, now go back to Norway and accept a tenured position at PRIO”. I told myself, I remember, that since I didn’t particularly like Norwegian winters, I could do a lot of fieldwork in Cyprus and the Middle East. And the other part of my brain, the less responsible part, said, “Yeah, but if Kevin Clements would resign as Secretary General of International Alert, you could have that job and move to London”.[6] This was an idea encouraged in me by an old friend of mine, John Marks, founder and head of Search for Common Ground, the biggest peacebuilding NGO.

So, about a week later, I was reading The Economist and saw the advert for the job, and I applied. The interview was in August of 2003. That afternoon, after the interview, I went down to see my sister. We were having a glass of wine in the garden and she asked me, “Now, so when you get this job and move to London, where are you going to live?”

And I told her, you know, not to be silly because I’m probably not going to get this job. And at that point, my phone rang, and she said, “There, they’re calling to offer you the job.” I scoffed at her, of course, but actually it was a phone call offering me the position.

How do you assess your time at International Alert?

International Alert was the second organisation I arrived at in the aftermath of a crisis. There had been one crisis in the mid-1990s, and then Kevin Clements arrived as Secretary General and picked it up and put it back together a bit. But then another set of problems emerged, causing frustration. One issue was a structural hole in the finances of about 5–10 percent, somewhere between 200 and 400 thousand pounds a year.

Income was insufficient but they had been saved from crisis in the previous few years by a series of strokes of good luck. They had eaten up their reserves, however. So, it was an organisation that was not in good shape. And I started there in December 2003, straight after I’d finished an evaluation of the peacebuilding experience of Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, and Norway. There was an international conference just outside Oslo to launch the report, and the following week I moved to London and dived straight into what I knew already was a bit of a mess. I believed that my PRIO experience would help me through.

We had a bad moment 14 or 15 months later in early 2005, when we had to make some staff redundant because the finances had run out of good luck. We had improved financial management, but we still needed to save about £200,000 in core spending. It could not be taken from project money, so we needed to slim down the administration. That’s a difficult thing to do. First of all, it’s hard on people who haven’t done anything wrong or performed their jobs badly. Second, it’s not necessarily a quick way to save money because you have the redundancy payment to come up with. Third, it risks weakening your capacity to manage the finances in the best possible way.

But we handled it well enough during the summer of 2005 that, by September, I was able to tell the staff that we didn’t foresee any more redundancies, so everybody could relax about that. This generated a kind of spirit of feeling, well, we’ve been through the fire now and survived. And among the staff there was a tougher and much more pragmatic set of attitudes to the practicalities of what we needed to do, how we needed to organise ourselves, in order to do the work of helping communities manage conflicts and build peaceful relations that we passionately believed in.

And again, as at PRIO before, a general feeling developed that, you know, we’re in the same boat and we either move that boat in the right direction or not. Generating that collective attitude seems to me to be the key to managing the kind of organisations I have been involved in throughout my working life.

Dan Smith with Ane Braein in Hebron, West Bank in 2003. Photo: Private archives

When I started, International Alert was working in about 16 or 17 countries. By the time I finished, we were working in 26 countries and had offices in 14 countries as well as the head office in London. Our staff had gone from about 75 or 80 people to around 215, but the number working in London had barely increased. We were running the Talking Peace festival in London with a few tens of thousands of people participating each year. So, we were doing advocacy work at home as well as in the field abroad. We had put ourselves in the leadership position of the arguments around climate change and insecurity with a report that we published in 2007 and we were contributing to a report to the G7 foreign ministers that came out in 2015: A New Climate for Peace.

We’re in the same boat and we either move that boat in the right direction or not. Generating that collective attitude seems to me to be the key to managing the kind of organisations I have been involved in throughout my working life.

I think International Alert was tremendous. I’m very proud of what we achieved in that time. I think we were part of the expansion of the zone of peace that happened up until about 2010–11. Amazingly enough, we actually managed to grow at the time of the financial crisis. Ironically, we came up with a business plan for expansion that was approved by the Board meeting on the Thursday before the Sunday when the Lehman Brothers collapsed, which is the event that’s normally taken as triggering the worldwide financial and economic crisis. But we managed to expand, even so, and hit our targets even though we hit them in somewhat different ways than we’d been expecting and planning. During that expansion, we opened up programmes in the Middle East, Ukraine, Central Asia, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Myanmar, and we kept our established programmes going in the South Caucasus, the Philippines, Nepal and Sri Lanka, and large parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

So, tell me about your next transition.

Sure. Towards the end of 2013, as I came up to the 10-year mark at Alert, I began to feel that I was getting close to what was enough. Not that I was at all fed up with the job or the people or anything. Far, far from it. And, still, in 2014 I drove through a new five-year strategic plan. But I began to feel, especially as I finished that strategic plan, that I’d just about given what I had to give to the organisation. Not that I was exhausted, but I was ceasing to be so creative. And it began to be time to look for a new challenge.

And then came SIPRI.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)

I had long known about SIPRI and used its Yearbooks and other publications since my early days at CND. But the business of moving to SIPRI, that started because my wife is Swedish. In the summer of 2014, she – my wife – raised the question of whether we could move away from London sometime not too far into the distant future. I asked, “Where?” She first tried Copenhagen, where she had lived for many years, but I said that although we know a lot of lovely people there, I don’t see what I recognise as a professional environment for me. Next, she mentioned Stockholm. And it occurred to me that, as well as the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), there is also the Stockholm Environmental Institute, there’s the Stockholm Resilience Centre, there’s Uppsala University, there’s also interesting work at the universities in Gothenburg and in Lund. So, I thought it could be a possibility and started thinking about how to make a transition into consultancy work. As I was doing that, I took a look at what SIPRI was doing and saw that SIPRI had an acting director. A couple of weeks later, it occurred to me that if SIPRI had an acting director, that must mean that the previous director whom I had met, Tilman Brück[7] had left and the institute might be looking for a new one. I thought the acting director would probably get the full appointment but looked into it anyway and saw that SIPRI was indeed advertising for a director, with the deadline for applications actually at the end of the week.

As background, I should mention that the previous time that the SIPRI directorship was advertised, I saw the announcement but wasn’t interested. Since then, however, SIPRI had started to do work on peace and development issues while maintaining its traditional lines of research, and I thought this was an intriguing balance. I had been to an event in spring 2014, and was impressed. So, I felt SIPRI had begun to change in a way that I found interesting. That event, by the way, is now the annual Stockholm Forum on Peace and Development, co-hosted with the Swedish MFA, with several hundred people attending in 2019 and, in 2020 when we took it online, some 3,500 registered participants and several thousand viewers on YouTube for some of the main sessions.

So, back to the story: I found out about the deadline and how to apply while I was in Dubai at a World Economic Forum meeting. And while there, our Lebanon office asked me to go to Beirut at the end of the week, to open a conference where the Minister of Interior was going to be speaking. So, I came back to London from Dubai and booked another flight to Beirut two days later. On my way to the airport, I realised that I hadn’t talked to my wife about the SIPRI thing, so I called her from the cab and explained it. And she said, “Well, you know, if you’re potentially interested this time, it does no harm. Write the letter and think about it later.” So I flew overnight to Beirut, got off the plane and got to the hotel, showered and changed, made the opening remarks to the conference where the Minister of Interior was going to speak, snuck out as soon as I could and staggered upstairs to get some sleep, woke up, wrote an application letter and sent it in about half an hour before the deadline. Then I was invited to an interview in January 2015 and was appointed a few weeks later.

Photo: Private archives

Three Narrowly but Deeply Divided Cultures

How do you see the differences between English, Swedish, and Norwegian culture? Have you thrived in all of them?

I think that English culture, because it’s where I was brought up, is what I feel most comfortable with, even though when I came back from Norway after a decade, I realised there were numerous things that had moved on really fast. Of course, a man in his early fifties, as I was when I came back, is in a different position from a man in his early forties, which is what I was when I left. So, it can also have to do with aging.

But I think even now, when I go back and visit England from Stockholm, that’s where I feel most comfortable, despite all the things that are strange and weird. London is an almost wholly dysfunctional city. I mean, it takes you an hour to get from anywhere to anywhere. You can be in one part of Hackney and try to get to central London and it will take you an hour; or you can be in one part of Hackney wanting to get to another part of Hackney, and it will still take you an hour. It’s just ridiculous, and how people manage to live there I don’t know, and I did it for 12 years. So, there you go.

Every country is a bunch of different countries and, as they say, London is a collection of different villages. It is an enormously cosmopolitan place with something like 300 native languages spoken. And as well as that diversity, there is massive social inequality and it is in your face all the time. When the Grenfell Tower fire occurred in 2017, one of the things that horrified people was that this building with completely unsafe building standards is located in the richest borough in England. So, you have millionaires and billionaires living within a stone’s throw of this impoverished tower block.

London is a collection of different villages. It is an enormously cosmopolitan place with something like 300 native languages spoken. And as well as that diversity, there is massive social inequality and it is in your face all the time.

Or owning apartments there, in which they don’t live.